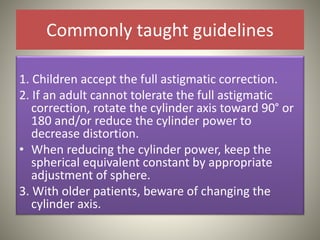

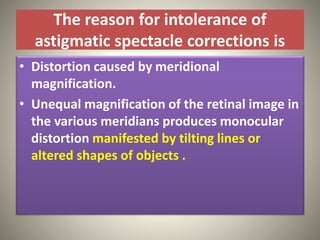

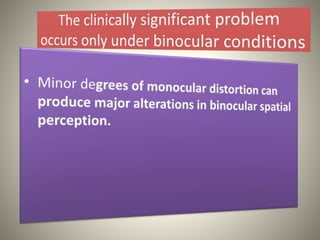

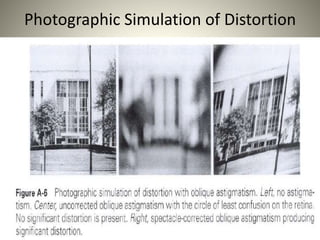

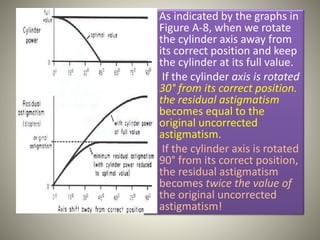

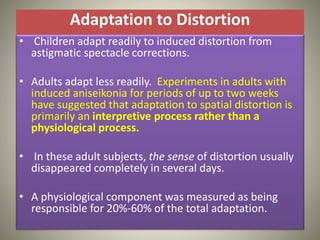

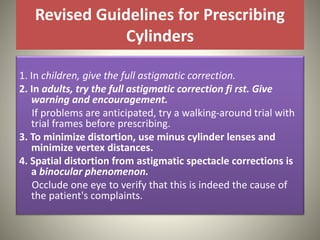

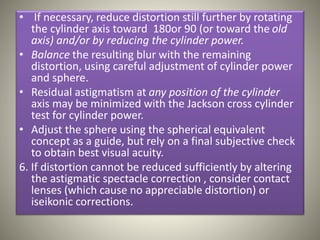

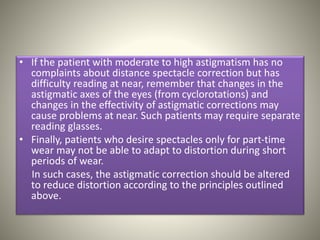

This document discusses guidelines for prescribing astigmatic corrections and minimizing distortion caused by meridional magnification. It notes that full astigmatic corrections can cause intolerable binocular spatial distortion. To reduce distortion, it recommends using minus cylinder lenses, minimizing vertex distance, rotating the cylinder axis toward 90° or 180°, and reducing cylinder power - balancing the resulting blur with remaining distortion. The Jackson cross cylinder test can minimize residual astigmatism from altered corrections. Adaptation usually alleviates distortion within a few days for adults.