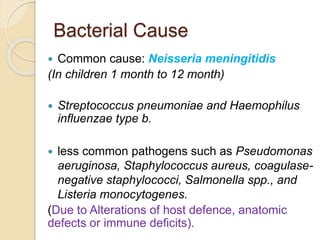

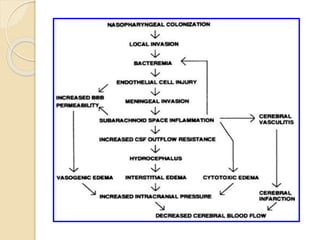

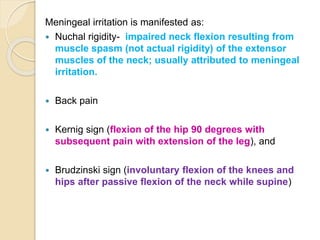

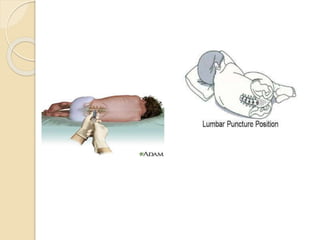

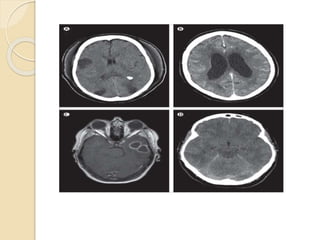

Meningitis is an inflammation of the protective membranes covering the brain and spinal cord, primarily caused by viral or bacterial infections. Bacterial meningitis is severe and can lead to significant complications, with common pathogens including Neisseria meningitidis and Streptococcus pneumoniae. Diagnosis typically involves CSF analysis and blood cultures, while prevention includes vaccinations and antibiotic prophylaxis.