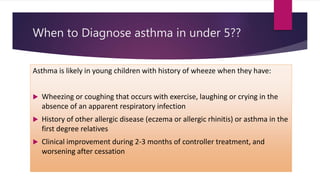

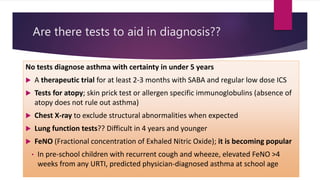

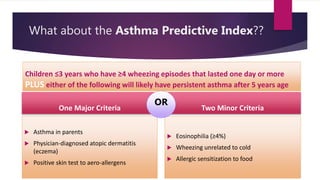

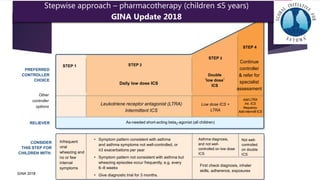

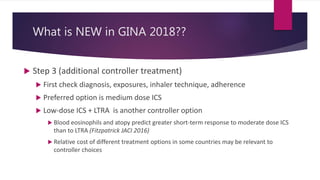

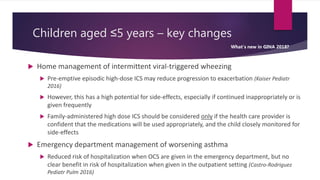

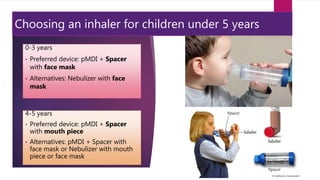

The document discusses pediatric asthma, including when to diagnose it in children under 5 years old. Key points include using a therapeutic trial and symptoms like exercise-induced wheezing to make a diagnosis. Tests can include skin prick tests and FeNO to aid diagnosis but not confirm it. The Asthma Predictive Index uses factors like eczema and family history to predict later asthma. Treatment follows GINA guidelines with a stepwise approach starting with SABAs and considering ICS, LTRAs, and doubling ICS doses if needed. Environmental controls and asthma education are also important for management.