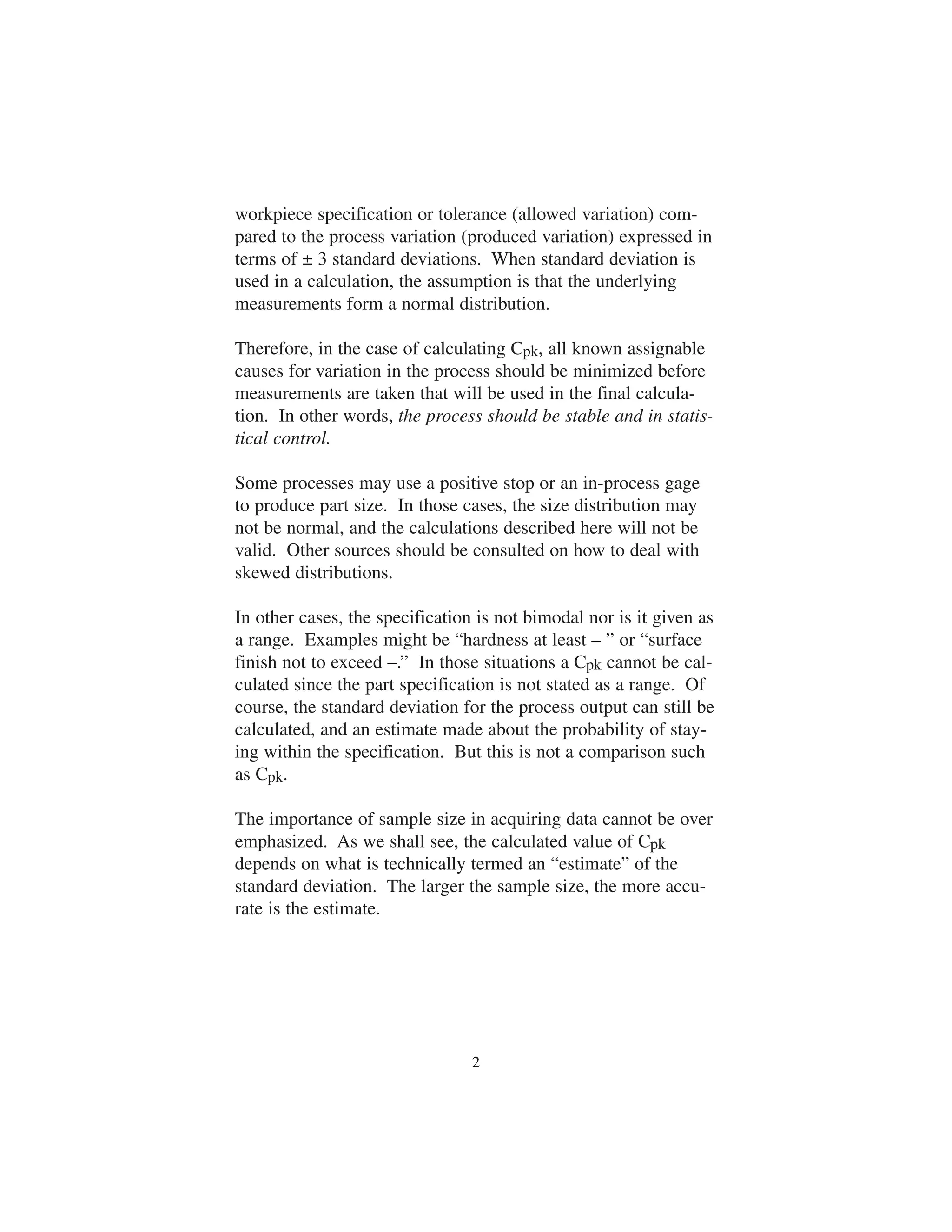

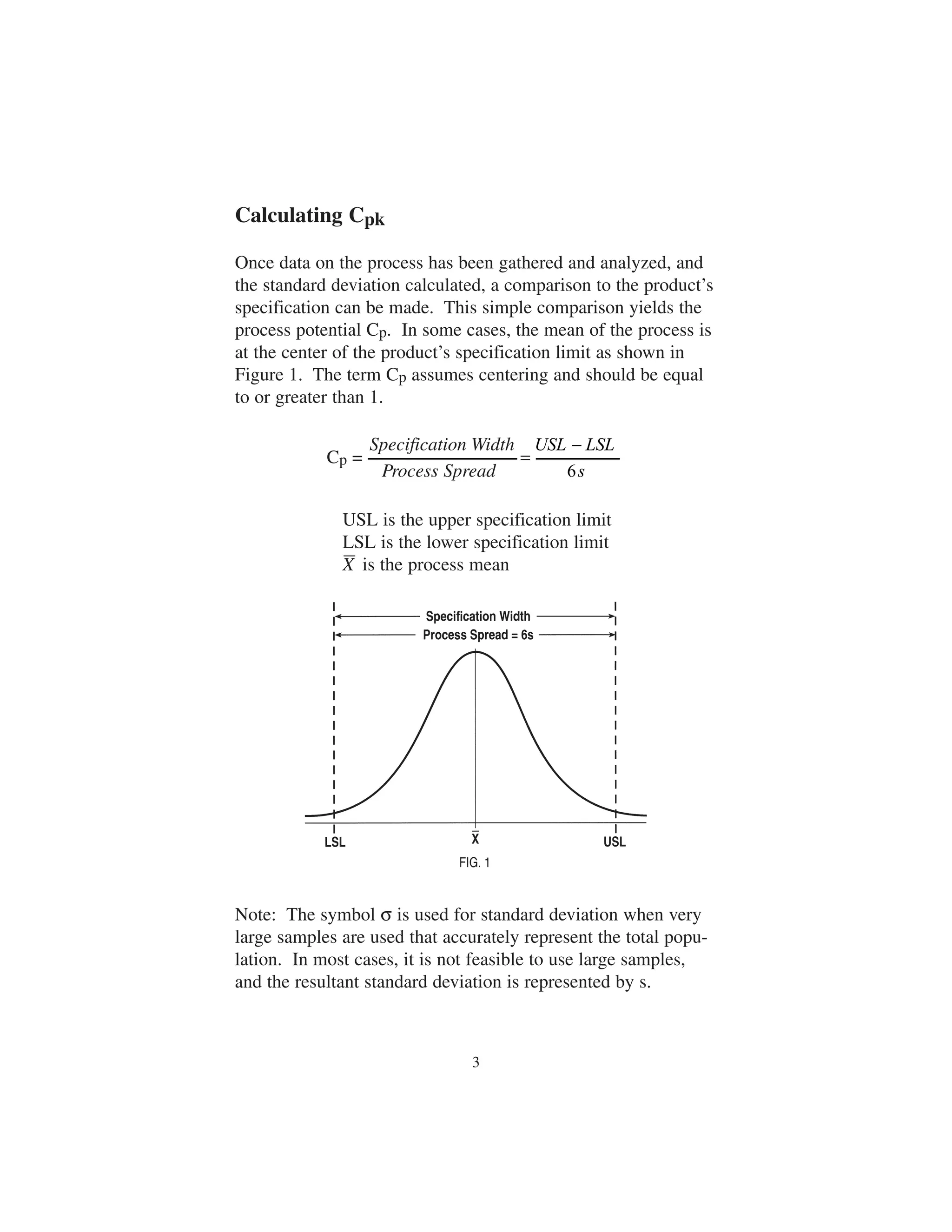

This document provides guidance on calculating and interpreting the process capability index Cpk. It defines Cpk as a ratio that compares the specification tolerance to the process variation expressed in terms of standard deviations. It explains how to calculate Cpk and discusses factors that influence Cpk values such as sample size, process centering, and measurement uncertainty. The document also provides examples of the expected defective parts per million that correspond to different Cpk values and factors to consider when improving Cpk, such as machine, tooling, workholding, and workpiece variables.

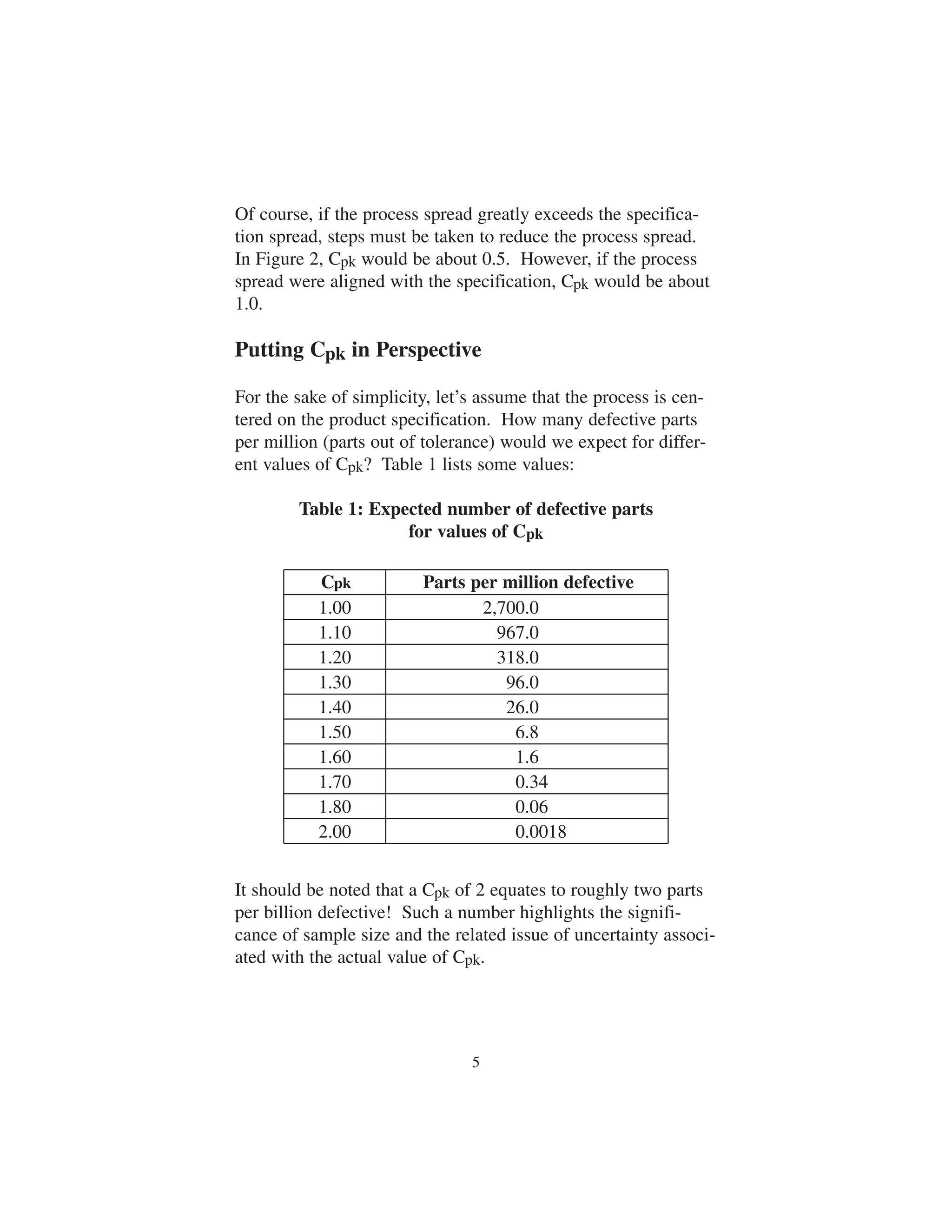

![Cpk A Guide to Using Cpk

a Process Capability Index

LSL

Cpk = Min [ U S L , ] _ X X _LSL

3s 3s

Specification Width

Process Spread

X USL](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cpkguide0211tech1-141107003933-conversion-gate01/75/Cpk-guide-0211_tech1-1-2048.jpg)

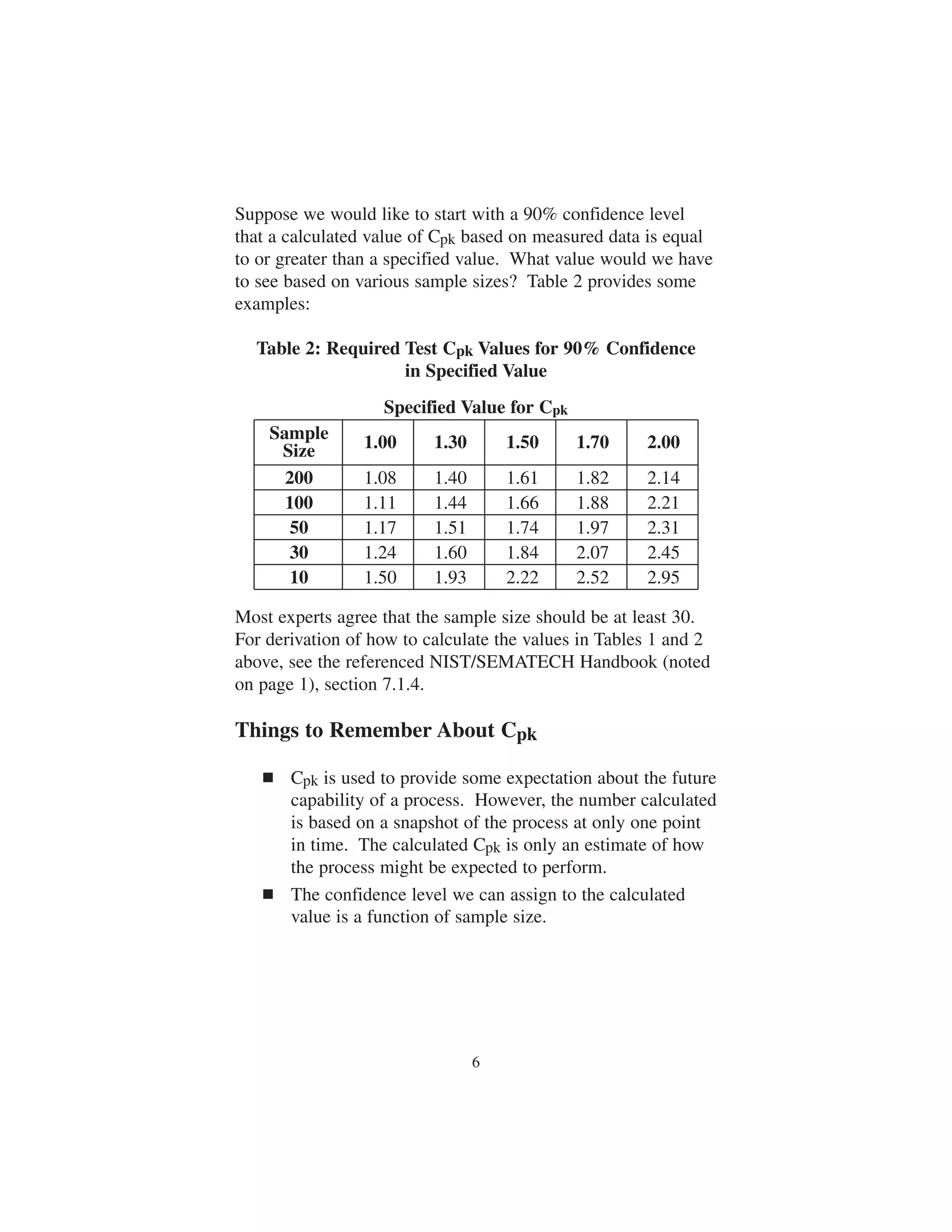

![However, in most cases, the process will not be centered on the

specification as shown in Figure 2. The actual process capabili-ty

Cpk then becomes

X Nearest Specificat ion Limit

X Nearest Specification Limit

USL X

−

X LSL

In Figure 2, the nearest specification limit is USL. An

inspection of Figure 2 will show that the first step in increasing

Cpk should be to take action to align the center of the process

spread with the center of the specification spread. This

assumes that the two spreads are close to equal, or the process

spread is actually less than the specification spread.

4

s

3

−

s

3

−

s

3

Cpk =

This is usually stated as

Cpk = Min [ , ]

FIG. 2](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/cpkguide0211tech1-141107003933-conversion-gate01/75/Cpk-guide-0211_tech1-7-2048.jpg)