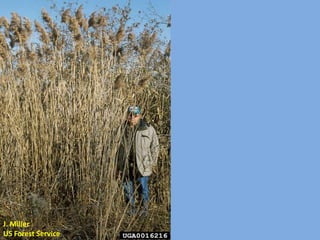

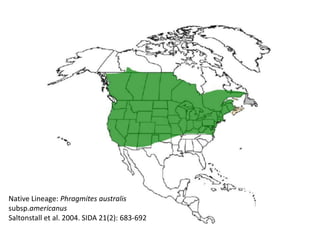

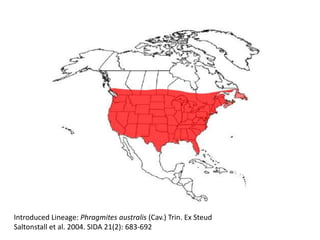

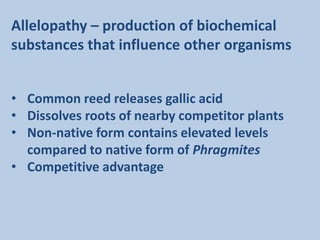

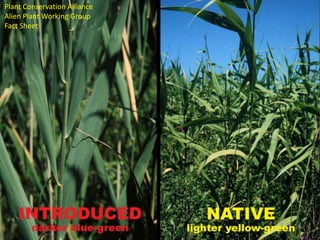

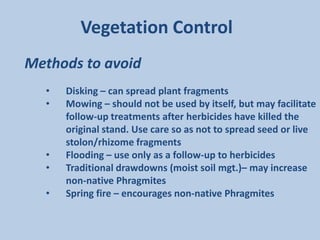

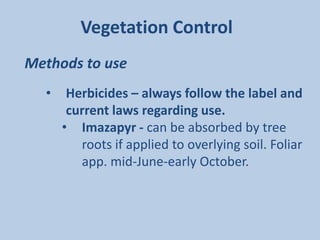

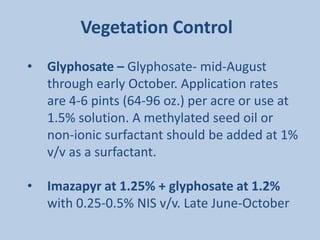

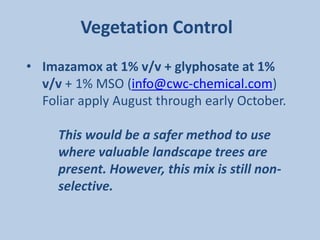

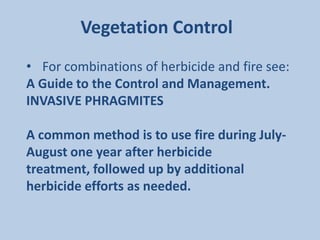

This document discusses the non-native common reed (Phragmites australis), including its invasive characteristics and methods for control and management. The non-native common reed forms dense monocultures that degrade wildlife habitat and increase fire risk. It has competitive advantages over native plants through elevated levels of allelopathic biochemicals. Effective control methods include applying herbicides like imazapyr and glyphosate in late summer or fall. Follow-up treatments may use fire or additional herbicides to prevent regrowth. Long-term monitoring is needed to manage the invasive populations over time.