This document provides an overview of global poultry production trends. It notes that poultry meat and egg production have increased the most compared to other animal sectors. Poultry is well positioned to meet growing global demand for protein as the world's population increases. Key factors that will influence future poultry production include population growth and urbanization, especially in developing countries, as well as concerns about food safety and nutrition. Poultry production systems have improved efficiency and will continue playing an important role in global food security.

![171CHAPTER 4

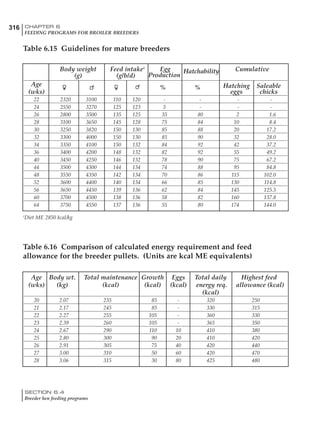

FEEDING PROGRAMS FOR LAYING HENS

SECTION 4.2

Feed and energy intake

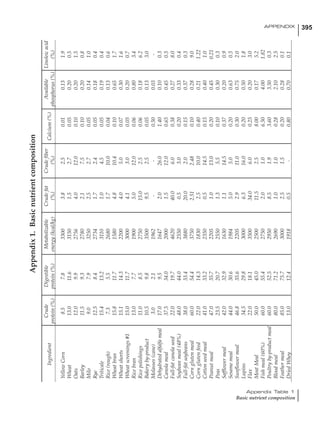

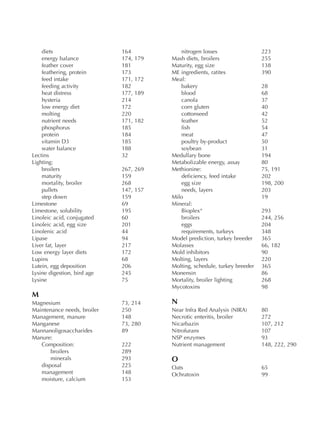

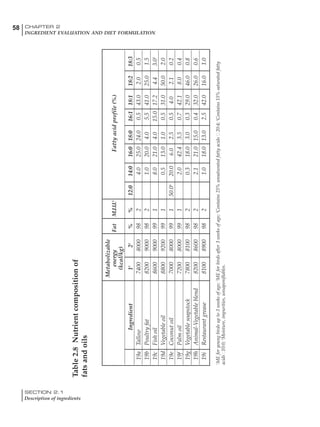

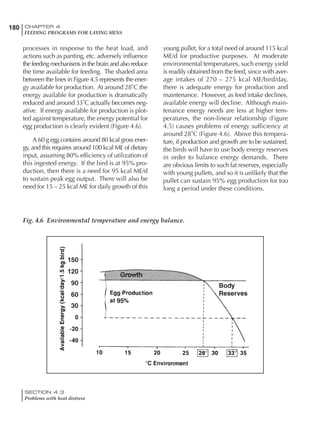

Table 4.6 Daily nutrient needs for Leghorn birds.

Table 4.7 Feed intake of Leghorns as influenced by body weight, egg

production, egg weight and environmental temperature1

Body weight Egg production Egg weight Temperature

Body wt Intake Egg production Intake Egg wt Intake ºC Intake

(g) (g/d) (%) (g/d) (g) (g/d) (g/d)

1200 92.7 98 100.5 50 90.8 10 102.2

1250 94.9 94 98.8 55 94.0 15 102.1

1300 97.1 90 97.1 60 97.1 20 97.1

1350 99.3 86 95.4 65 100.3 25 92.1

1400 101.5 82 93.8 70 103.4 30 87.1

23g 1 g 2.4% 1 g 1.6 g 1 g 1ºC 1 g

1 Assumes 1300 g body weight, 90% egg production, 60 g egg weight and 20 C as the standard, with diet at 2850 kcal/kg

At any given time, it is necessary to adjust diet

specifications according to the actual feed intake

of the flock. Within a single strain it is possible

to see a ± 15 g variance in feed intake at any age

related to stage of maturity, egg mass, body

size and most importantly, environmental tem-

perature.

It is possible to predict energy needs, and hence

feed intake, based on knowledge of the major

variables. The equation most commonly used

is described below. Using this equation, Table

4.7 was developed with variable inputs of body

weight, egg production, egg weight and envi-

ronmental temperature. Feed intake was calculated

assuming a diet energy level of 2850 kcal ME/kg.

Energy (kcal ME/bird/day) = [Body weight (kg)] [170 – 2.2 x ºC]

+ [2 x Egg mass/d (g)]

+ [5 x Daily weight gain (g)]

Age (wks)

18 – 32 32 – 45 45 – 60 60 – 70

Protein (g) 20 18.5 17.5 16

Metabolizable energy (kcal) 260 290 285 280

Calcium (g) 4.0 4.2 4.4 4.6

Av. Phosphorus (mg) 550 450 380 330

Methionine (mg) 500 430 390 340

TSAA (mg) 830 740 670 600

Lysine (mg) 950 840 780 730](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/commercialpoultrynutrition-130530001831-phpapp02/85/Commercial-poultry-nutritio-178-320.jpg)

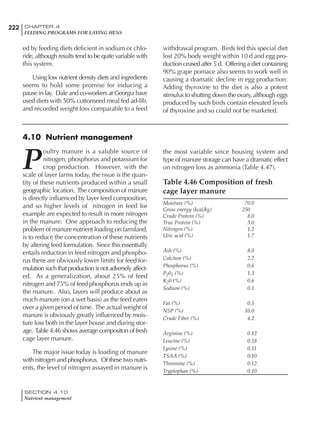

![330 CHAPTER 6

FEEDING PROGRAMS FOR BROILER BREEDERS

SECTION 6.5

Factors influencing feed and nutrient intake

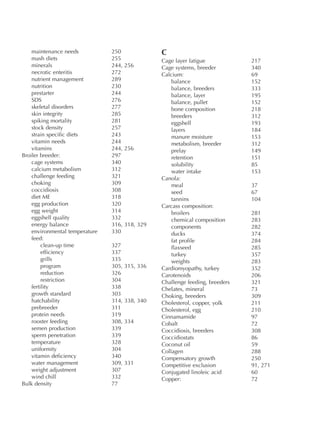

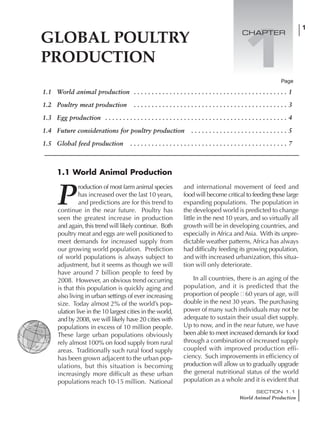

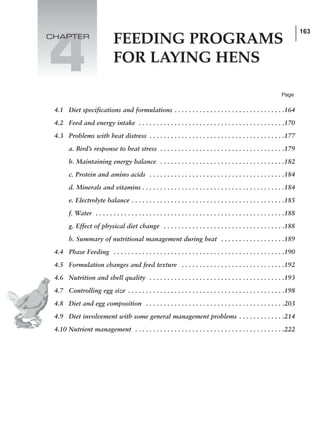

Effective temperature =[ (daytime high temper-

ature x 2) + (nighttime low temperature)]/3

For the above example, the calculation becomes:

[(26 x 2) + 8]/3 = 20ºC

The ‘effective’ temperature becomes 20ºC

rather than 17ºC as calculated by the tradition-

al method. The nighttime low of 8ºC is given less

emphasis because birds get an insulative effect

from sitting and huddling. These birds therefore

need less ‘extra’ heat in order to keep warm than

is predicted from simple thermometer meas-

urements. Table 6.28 shows calculations using

this same formula, at various day and night

temperatures. If we assume that 26ºC is an ideal

temperature for breeders then we can calculate

the extra feed needed for maintenance as effec-

tive temperature declines. If a diet provides 2850

kcal ME/kg, a 3 kg breeder will need an extra 1.5

g feed for each 1ºC decline in effective house tem-

perature. Table 6.28 shows such calculated

extra feed needed by breeders kept at various day

and night conditions relative to breeders kept in

an ideal environment of constant 26ºC.

The deleterious influence of a cold night

temperature is therefore not as significant as a

comparable cold temperature during daytime.

With a daytime temperature of 24ºC as an

example, we only have to feed an extra 12 g daily

in order to counteract a chilly night temperature

of 6ºC. Failure to make such an adjustment long

term will mean that the hen will either lose

weight and/or reduce egg output in an attempt

to conserve energy.

Another question often asked is how often

should feed intake be adjusted in order to accom-

modate fluctuating environmental temperatures?

Weather predictions can be notoriously inaccu-

rate, and so day-to-day adjustments seem unwise,

as well as being impractical for the farm staff. The

bird does have a quickly usable store of energy

Table 6.28 Effect of temperature on increased feed allowance relative to 26ºC

standard (gram/hen/day)1

Daytime Nighttime temperature (ºC)

temperature

26 24 22 20 18 16 14 12 10 8 6 4 2 0 -2

(ºC)

26 0 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14

24 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16

22 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18

20 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20

18 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22

16 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24

14 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26

12 22 23 24 25 26 27 28

10 25 26 27 28 29 30

8 28 29 30 31 32

6 30 31 32 33

1

Feed @ 2850 kcal ME/kg](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/commercialpoultrynutrition-130530001831-phpapp02/85/Commercial-poultry-nutritio-337-320.jpg)