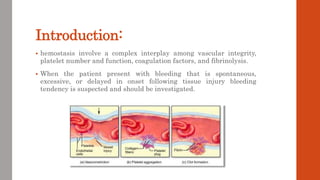

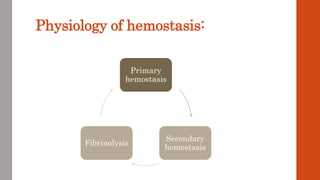

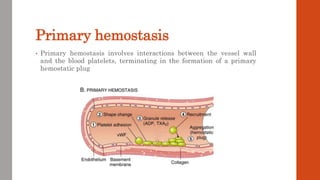

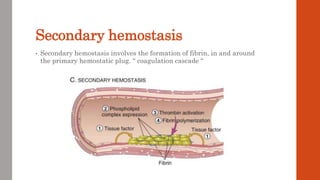

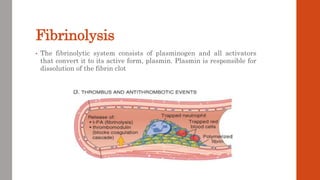

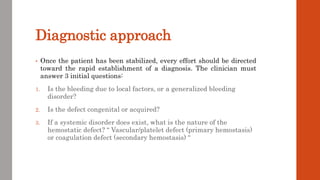

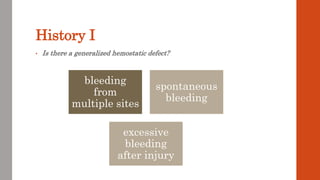

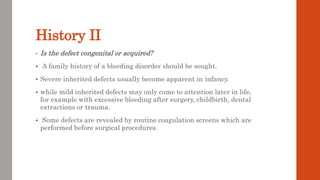

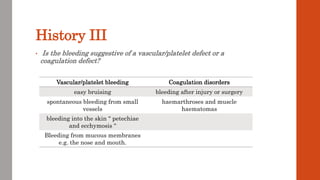

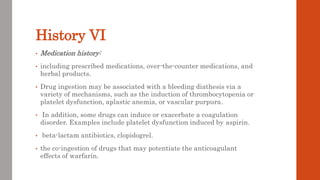

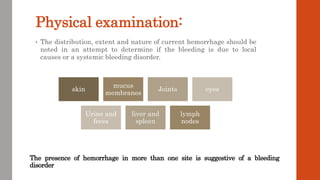

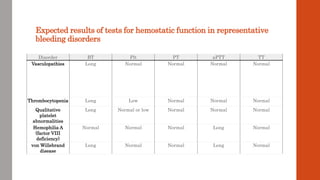

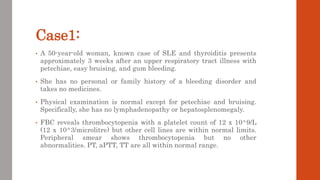

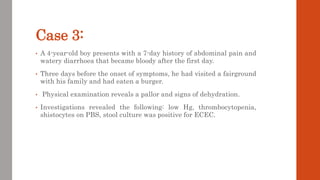

The document outlines the complex mechanisms of hemostasis and the diagnostic approach for patients presenting with bleeding tendencies, emphasizing the importance of distinguishing between local and systemic causes as well as congenital and acquired defects. It discusses the physiological aspects of primary and secondary hemostasis, common bleeding disorders, and details various laboratory investigations to assess hemostatic function. Case studies illustrate specific conditions such as idiopathic thrombocytopenic purpura, hemophilia A, and hemolytic uremic syndrome, highlighting their clinical presentations and management options.