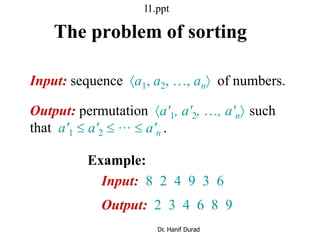

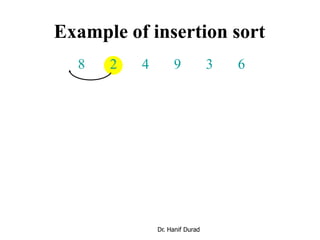

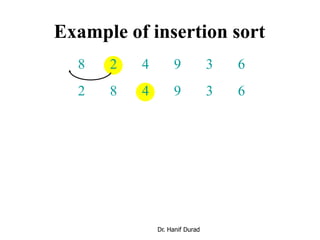

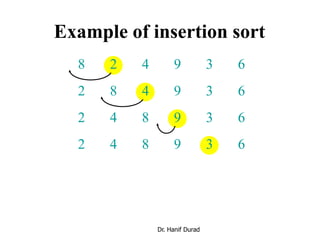

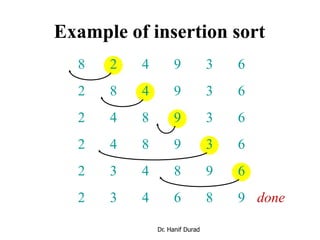

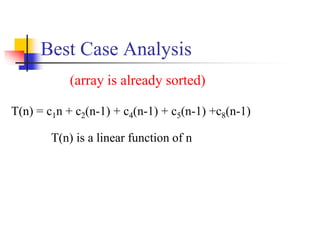

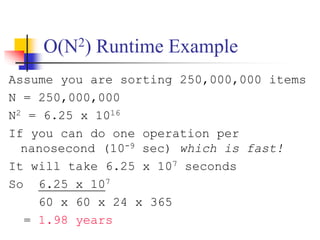

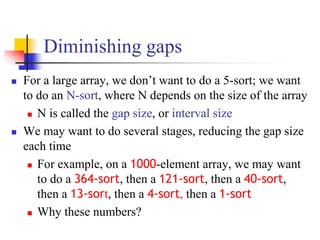

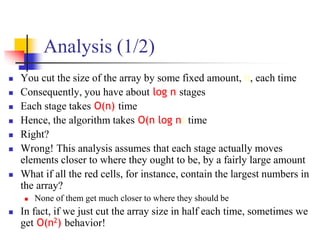

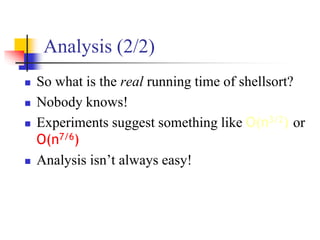

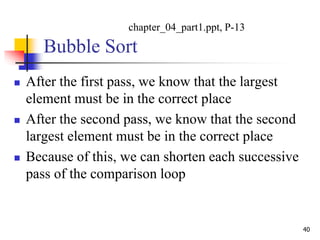

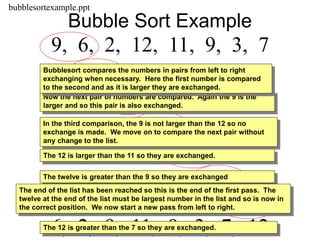

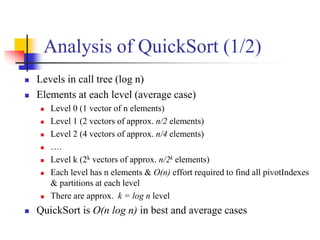

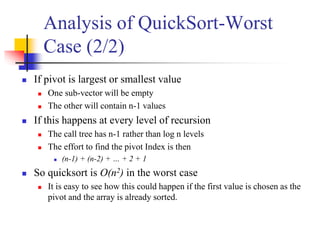

This document provides an overview of sorting algorithms including bubble sort, insertion sort, shellsort, and others. It discusses why sorting is important, provides pseudocode for common sorting algorithms, and gives examples of how each algorithm works on sample data. The runtime of sorting algorithms like insertion sort and shellsort are analyzed, with insertion sort having quadratic runtime in the worst case and shellsort having unknown but likely better than quadratic runtime.

![Insertion sort

INSERTION-SORT (A, n) ⊳ A[1 . . n]

for j ← 2 to n

do key ← A[ j]

i ← j – 1

while i > 0 and A[i] > key

do A[i+1] ← A[i]

i ← i – 1

A[i+1] = key

“pseudocode”

i j

key

sorted

A:

1 n

Dr. Hanif Durad](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter4ds-190904110928/85/Chapter-4-ds-11-320.jpg)

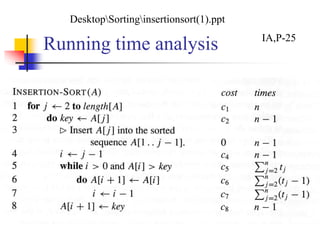

![Some explanation

“times” column refers to how many times

each stmt is executed (max)

n = length[A]

tj = # times the while loop test in line 5 is

executed for that value of the index j](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter4ds-190904110928/85/Chapter-4-ds-24-320.jpg)

![Worst Case Analysis

So T(j) = j, for j = 2,3,…,n

Must compare each element A[j] w/ each element

in the entire sorted subarray A[1..j-1]

Thus, T(n) = c1n + c2(n-1) + c4(n-1) + c5(n(n+1)/2 – 1)

+ c6(n(n-1)/2) + c7(n(n-1)/2) + c8(n-1)

T(n) is a quadratic function of n

(array reverse-sorted)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter4ds-190904110928/85/Chapter-4-ds-26-320.jpg)

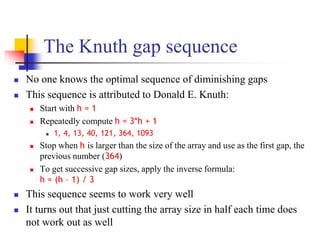

![Shellsort

ShellSort(A, n)

1. h 1

2. while h n {

3. h 3h + 1

4. }

5. repeat

6. h h/3

7. for i = h to n do {

8. key A[i]

9. j i

10. while key < A[j - h] {

11. A[j] A[j - h]

12. j j - h

13. if j < h then break

14. }

15. A[j] key

16. }

17. until h 1

Comp 122

When h=1, this is insertion sort.

Otherwise, performs insertion

sort on keys h locations apart.

h values are set in the outermost

repeat loop. Note that they are

decreasing and the final value is 1.

DSAL COMP 550-001, 04-sorting.ppt](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter4ds-190904110928/85/Chapter-4-ds-34-320.jpg)

![Bubble Sort Algortithm

1. for i←1 to length[A]

2. for j←length[A] down to i+1

3. if (A[j] < A[j-1])

4. swap(A[j] ,A[j-1]);

Dr. Hanif Durad 47

DS-1, P-453](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter4ds-190904110928/85/Chapter-4-ds-47-320.jpg)

![Selection Sort Algorithm

Input: An array A[1..n] of n elements.

Output: A[1..n] sorted in nondecreasing order.

1. for i 1 to n - 1

2. k i

3. for j i + 1 to n {Find the i th smallest element.}

4. if A[j] < A[k] then k j

5. end for

6. if k i then interchange A[i] and A[k]

7. end for](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter4ds-190904110928/85/Chapter-4-ds-54-320.jpg)

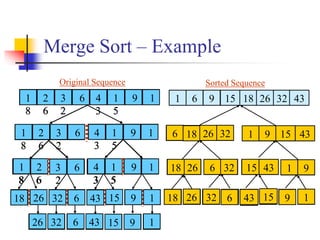

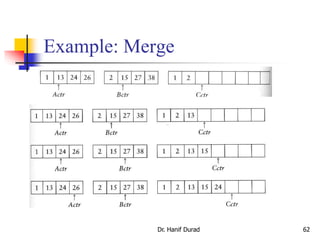

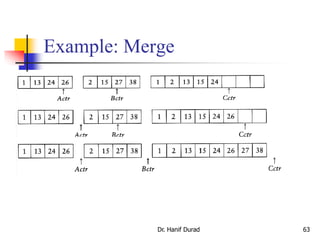

![How to merge two Arrays?

Dr. Hanif Durad 61

Input: two sorted array A and B

Output: an output sorted array C

Three counters: Actr, Bctr, and Cctr

initially set to the beginning of their respective arrays

(1) The smaller of A[Actr] and B[Bctr] is copied to the next entry in C,

and the appropriate counters are advanced

(2) When either input list is exhausted, the remainder of the other list is

copied to C

D:DSALCOMP171 Data Structures and Algorithmmergesort.ppt](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter4ds-190904110928/85/Chapter-4-ds-61-320.jpg)

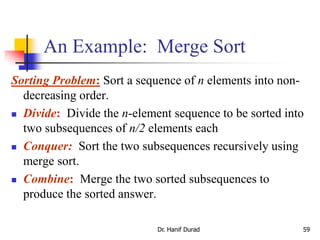

![Merge Sort Algorithm

The procedure MERGE-SORT(A, p, r) sorts the elements in the

sub-array A[ p…r].

The divide step simply computes an index q that partitions A[ p…r]

into two sub-arrays: A[ p…q], containing n/2 elements, and A[ q +

1…r], containing n/2 elements.

To sort the entire sequence A ={A[1], A[2], . . . ,

A[ n]}, we make the initial call MERGE-SORT( A, 1, length[ A]),

where length[ A] = n.

02_Getting Started_2.ppt](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter4ds-190904110928/85/Chapter-4-ds-65-320.jpg)

![L1.66

66

// Copy A[p, q] to L

// Copy A[q+1, r] to R

// Compute # of elements in L

// Compute # of elements in R

// Put a sentinel card at the end of L

// Put a sentinel card at the end of R

// Put the smaller of

L[i] and R[j] to A[K

unit03.ppt](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter4ds-190904110928/85/Chapter-4-ds-66-320.jpg)

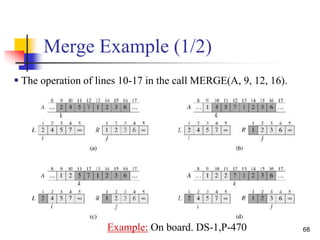

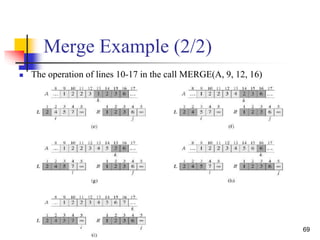

![67

Merge Sort

The key operation of the merge sort algorithm is the

merging of two sorted sequences in the "combine" step. To

perform the merging, we use an auxiliary procedure

MERGE(A, p, q, r), where A is an array and p, q, and r

are indices numbering elements of the array such that p ≤ q

< r.

The procedure assumes that the sub-arrays A[ p…q] and

A[ q + 1…r] are in sorted order. It merges them to form a

single sorted sub-array that replaces the current sub-array

A[ p…r].](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter4ds-190904110928/85/Chapter-4-ds-67-320.jpg)

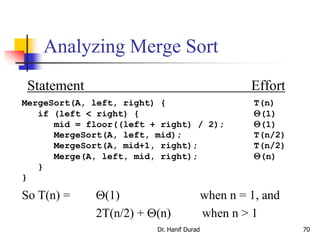

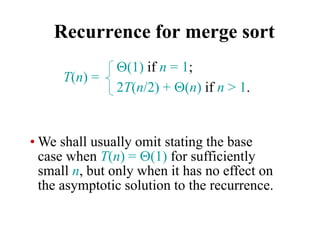

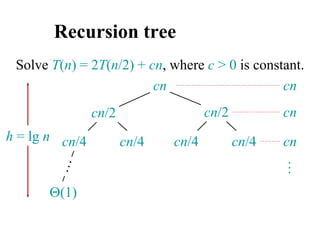

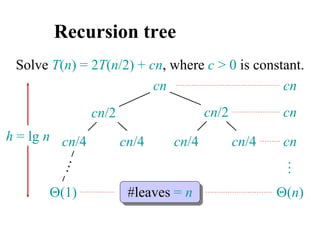

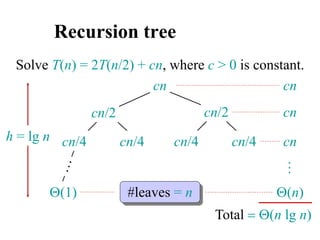

![Analyzing merge sort

MERGE-SORT A[1 . . n]

1. If n = 1, done.

2. Recursively sort A[ 1 . . n/2 ]

and A[ n/2+1 . . n ] .

3. “Merge” the 2 sorted lists

T(n)

(1)

2T(n/2)

(n)

Sloppiness: Should be T( n/2 ) + T( n/2 ) ,

but it turns out not to matter asymptotically.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter4ds-190904110928/85/Chapter-4-ds-71-320.jpg)

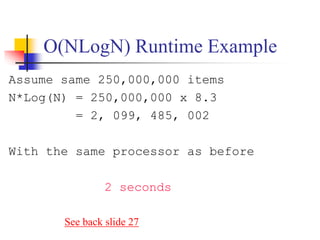

![Introduction

Another divide-and-conquer recursive algorithm, like

mergesort

Quicksort pros [advantage]:

Sorts in place

Sorts O(n lg n) in the average case

Very efficient in practice , it’s quick

Quicksort cons [disadvantage]:

Sorts O(n2) in the worst case

And the worst case doesn’t happen often … sorted

Dr. Hanif Durad 87

D:DSALCOMP171 Data Structures and Algorithmqsort.ppt

C:Documents and SettingsAdministratorDesktopSortingquicksortalgo_Lecture 6 quick_sor.ppt](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter4ds-190904110928/85/Chapter-4-ds-87-320.jpg)

![Quicksort Example 2 (1/7)

150 300 650 550 800 400 350 450

scanUp scanDown

v[0] v[9]v[8]v[7]v[6]v[5]v[4]v[3]v[2]v[1]

pivot

500 900

The quicksort algorithm uses a series of recursive calls to partition a

list into smaller and smaller sublists about a value called the pivot.

Example: Let v be a vector containing 10 integer values:

v = {800, 150, 300, 650, 550, 500, 400, 350, 450,

900}

D:DSALCLRlect6

Dr. Hanif Durad](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter4ds-190904110928/85/Chapter-4-ds-91-320.jpg)

![Quicksort Example 2 (3/7)

Before the exchange

After the exchange and updates to scanUp and scanDown

150 300 650 550 800 400 350 450

scanUp scanDown

v[0] v[9]v[8]v[7]v[6]v[5]v[4]v[3]v[2]v[1]

pivot

500 900

150 300 450 550 800 400 350 650

scanUp scanDown

v[0] v[9]v[8]v[7]v[6]v[5]v[4]v[3]v[2]v[1]

pivot

500 900

Dr. Hanif Durad](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter4ds-190904110928/85/Chapter-4-ds-92-320.jpg)

![Quicksort Example 2 (3/7)

Before the exchange

After the exchange and updates to scanUp and scanDown

150 300 450 550 800 400 350 650

scanUp scanDown

v[0] v[9]v[8]v[7]v[6]v[5]v[4]v[3]v[2]v[1]

pivot

500 900

150 300 450 350 800 400 550 650

scanUp scanDown

v[0] v[9]v[8]v[7]v[6]v[5]v[4]v[3]v[2]v[1]

pivot

500 900

Dr. Hanif Durad](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter4ds-190904110928/85/Chapter-4-ds-93-320.jpg)

![Quicksort Example 2 (4/7)

Before the exchange

After the exchange and updates to scanUp and scanDown

150 300 450 350 800 400 550 650

scanUp scanDown

v[0] v[9]v[8]v[7]v[6]v[5]v[4]v[3]v[2]v[1]

pivot

500 900

150 300 450 350 400 800 550 650

scanUpscanDown

v[0] v[9]v[8]v[7]v[6]v[5]v[4]v[3]v[2]v[1]

pivot

500 900

Dr. Hanif Durad](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter4ds-190904110928/85/Chapter-4-ds-94-320.jpg)

![Quicksort Example 2 (4/7)

400 150 300 450 350 500 800 550 650

v[0] v[9]v[8]v[7]v[6]v[5]v[4]v[3]v[2]v[1]

900

Pivot in its final position

400 150 300 450 350 500 800 550 650

v[0] v[9]v[8]v[7]v[6]v[5]v[4]v[3]v[2]v[1]

v[0] - v[4] v[6] - v[9]

900

Dr. Hanif Durad](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter4ds-190904110928/85/Chapter-4-ds-95-320.jpg)

![Quicksort Example 2 (5/7)

pivot

300 150 400 450 350

scanUp

v[0] v[4]v[3]v[2]v[1]

Initial Values

scanDown

pivot

300 150 400 450 350

v[0] v[4]v[3]v[2]v[1]

scanUp

After Scans Stop

scanDown

150 300 400 450 350

v[0] v[4]v[3]v[2]v[1]

Dr. Hanif Durad](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter4ds-190904110928/85/Chapter-4-ds-96-320.jpg)

![pivot

650 550 800 900

scanUp

v[6] v[9]v[8]v[7]

Initial Values

scanDown

pivot

650 550 800 900

v[6] v[9]v[8]v[7]

scanUp

After Stops

scanDown

550 650 800 900

v[6] v[9]v[8]v[7]

Quicksort Example 2 (6/7)

Dr. Hanif Durad](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter4ds-190904110928/85/Chapter-4-ds-97-320.jpg)

![Quicksort Example 2 (7/7)

v[0] v[4]v[3]v[2]v[1] v[6] v[9]v[8]v[7]v[5]

150 900800650550500350450400300

400 450 350

v[4]v[3]v[2]

Before Partitioning

350 400 450

v[4]v[3]v[2]

After Partitioning

150 300 350 400 450 500

v[0] v[4]v[3]v[2]v[1]

550 650 800 900

v[6] v[9]v[8]v[7]v[5]

Dr. Hanif Durad](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter4ds-190904110928/85/Chapter-4-ds-98-320.jpg)

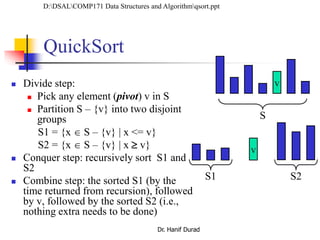

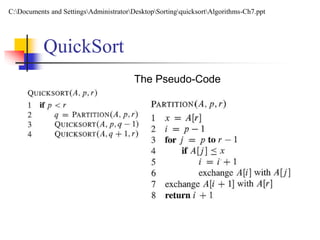

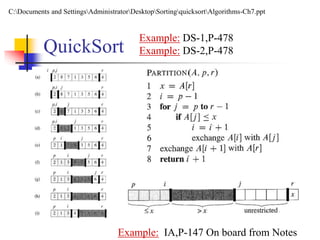

![QuickSort

Like in MERGESORT, we use Divide-and-Conquer:

1. Divide: partition A[p..r] into two subarrays A[p..q-1] and

A[q+1..r] such that each element of A[p..q-1] is ≤ A[q], and each

element of A[q+1..r] is ≥ A[q]. Compute q as part of this

partitioning.

2. Conquer: sort the subarrays A[p..q-1] and A[q+1..r] by recursive

calls to QUICKSORT.

3. Combine: the partitioning and recursive sorting leave us with a

sorted A[p..r] – no work needed here.

An obvious difference is that we do most of the work in the divide

stage, with no work at the combine one.

C:Documents and SettingsAdministratorDesktopSortingquicksortAlgorithms-Ch7.ppt](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter4ds-190904110928/85/Chapter-4-ds-99-320.jpg)

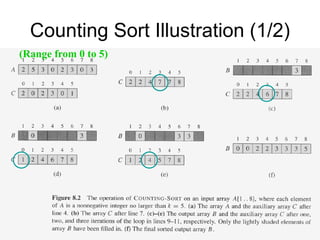

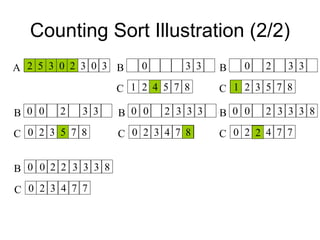

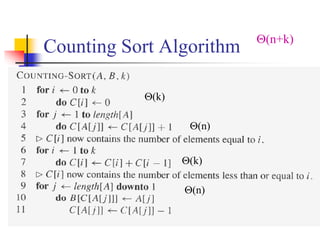

![Counting Sort Overview

Assumption: n input elements are integers in the range of 0

to k (integer).

(n+k) When k=O(n), counting sort: (n)

Basic Idea

For each input element x, determine the number of elements less

than or equal to x

For each integer i (0 i k), count how many elements whose

values are i

Then we know how many elements are less than or equal to i

Algorithm storage

A[1..n]: input elements

B[1..n]: sorted elements

C[0..k]: hold the number of elements less than or equal to i](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter4ds-190904110928/85/Chapter-4-ds-105-320.jpg)

![Counting Sort Is Stable

A sorting algorithm is stable if

Numbers with the same value appear in the output array

in the same order as they do in the input array

Ties between two numbers are broken by the rule that

which ever number appears first in the input array

appears first in the output array

Line 9 of counting sort: for jlength[A] down to 1

is essential for counting sort to be stable

What if for j 1 to length[A]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter4ds-190904110928/85/Chapter-4-ds-109-320.jpg)