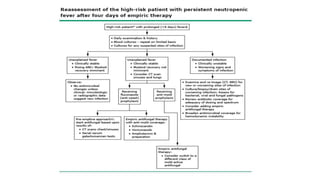

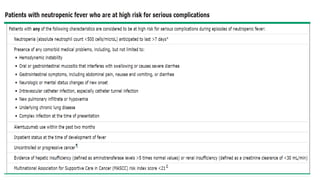

This document provides guidelines for the management of febrile neutropenia in cancer patients. It defines febrile neutropenia and outlines risks for serious infection. Initial assessment involves evaluating risk of complications to determine treatment approach. Empiric broad-spectrum antibacterial therapy should be initiated within 60 minutes of presentation to cover likely pathogens. The regimen may be modified based on infection source or persistence of fever. Early antifungal therapy should also be considered for high-risk patients.

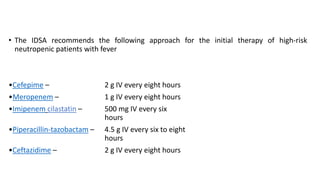

![ Anaerobic coverage is suggested to be included if there is evidence

of:

necrotizing mucositis,

sinusitis

periodontal cellulitis

perirectal cellulitis

intraabdominal infection

(including neutropenic enterocolitis [typhlitis]),

pelvic infection,

anaerobic bacteremia.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/chapter30febrileneutropenia-191105205123/85/Chapter-30-febrile-neutropenia-22-320.jpg)