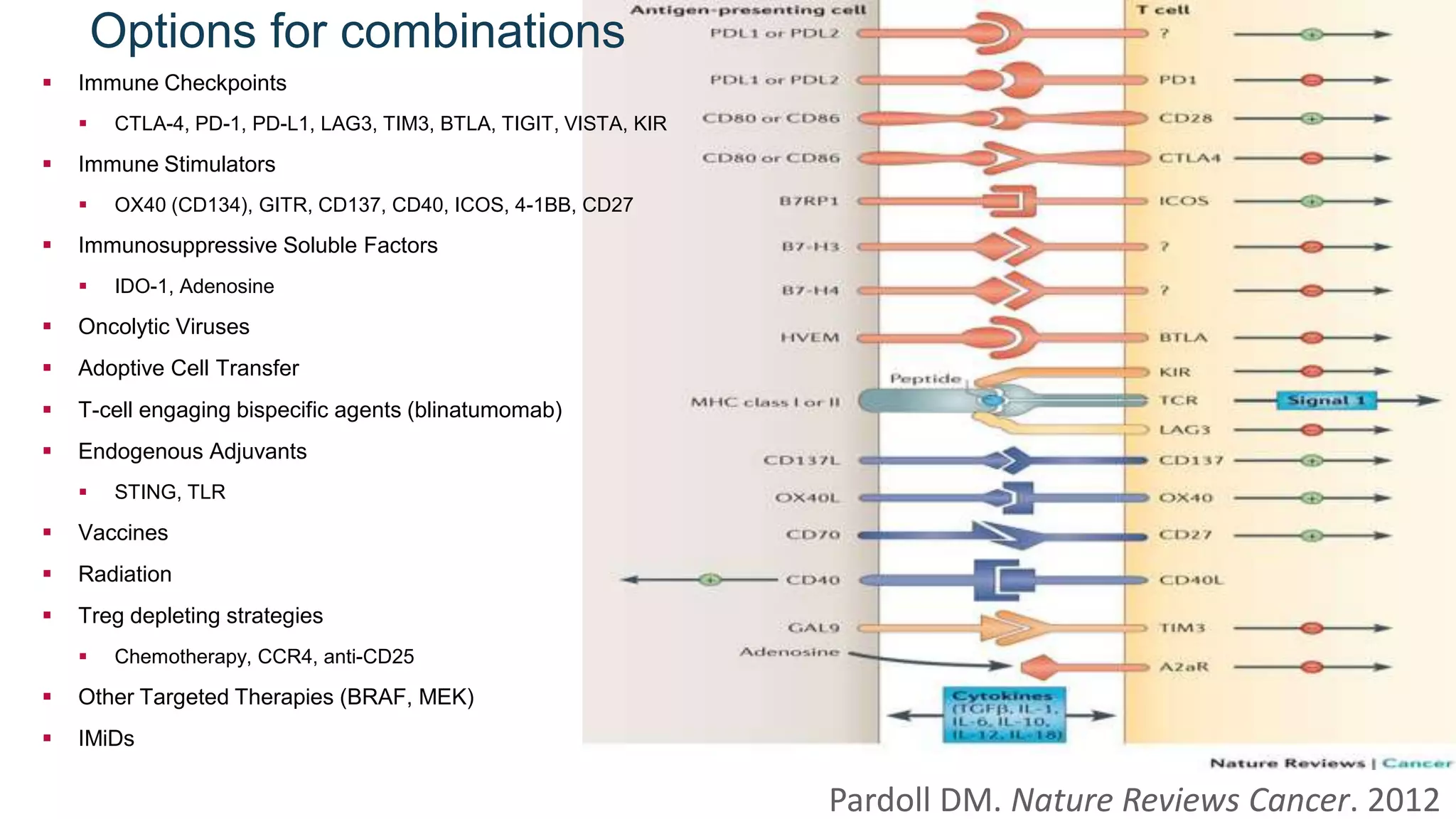

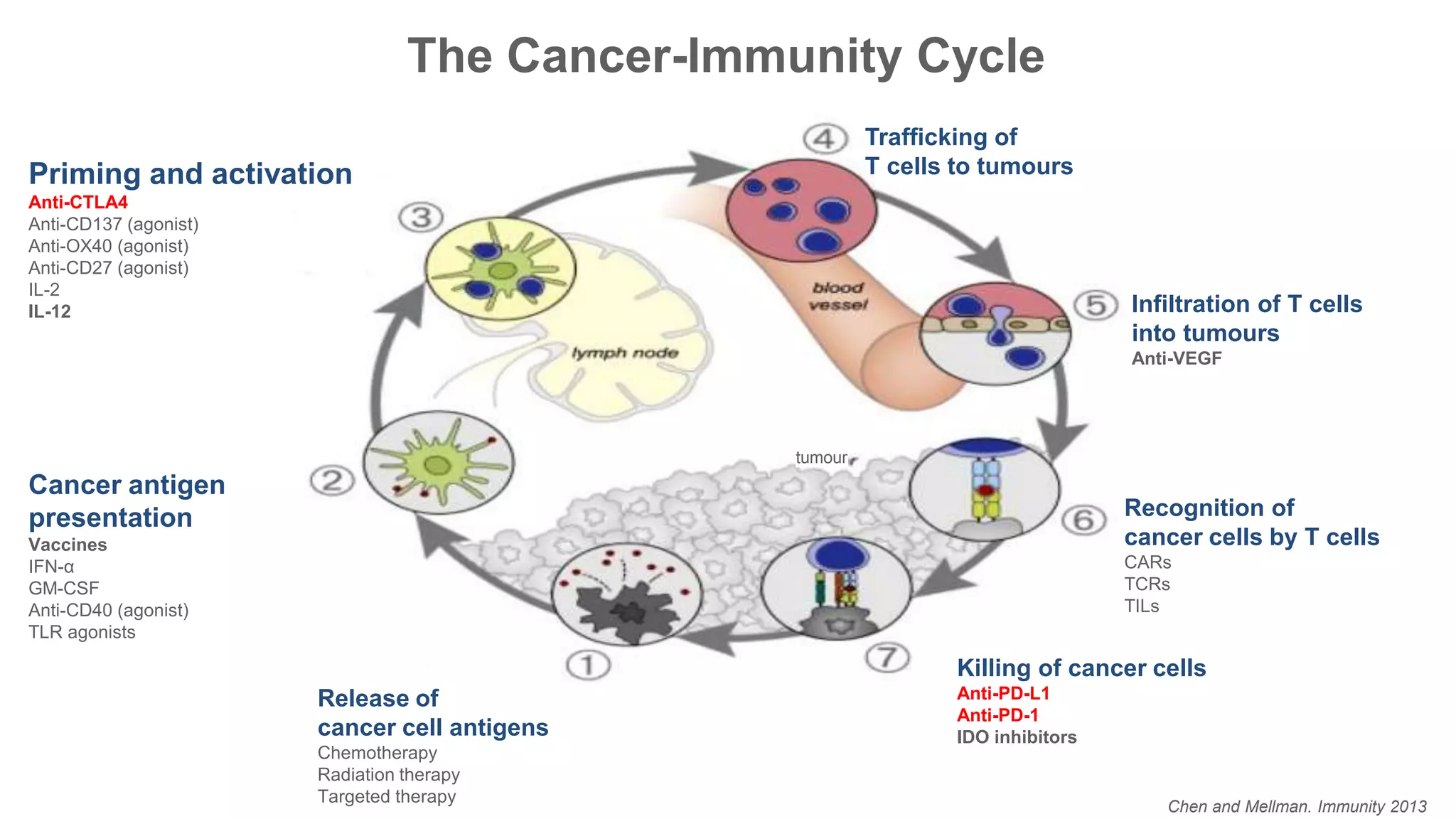

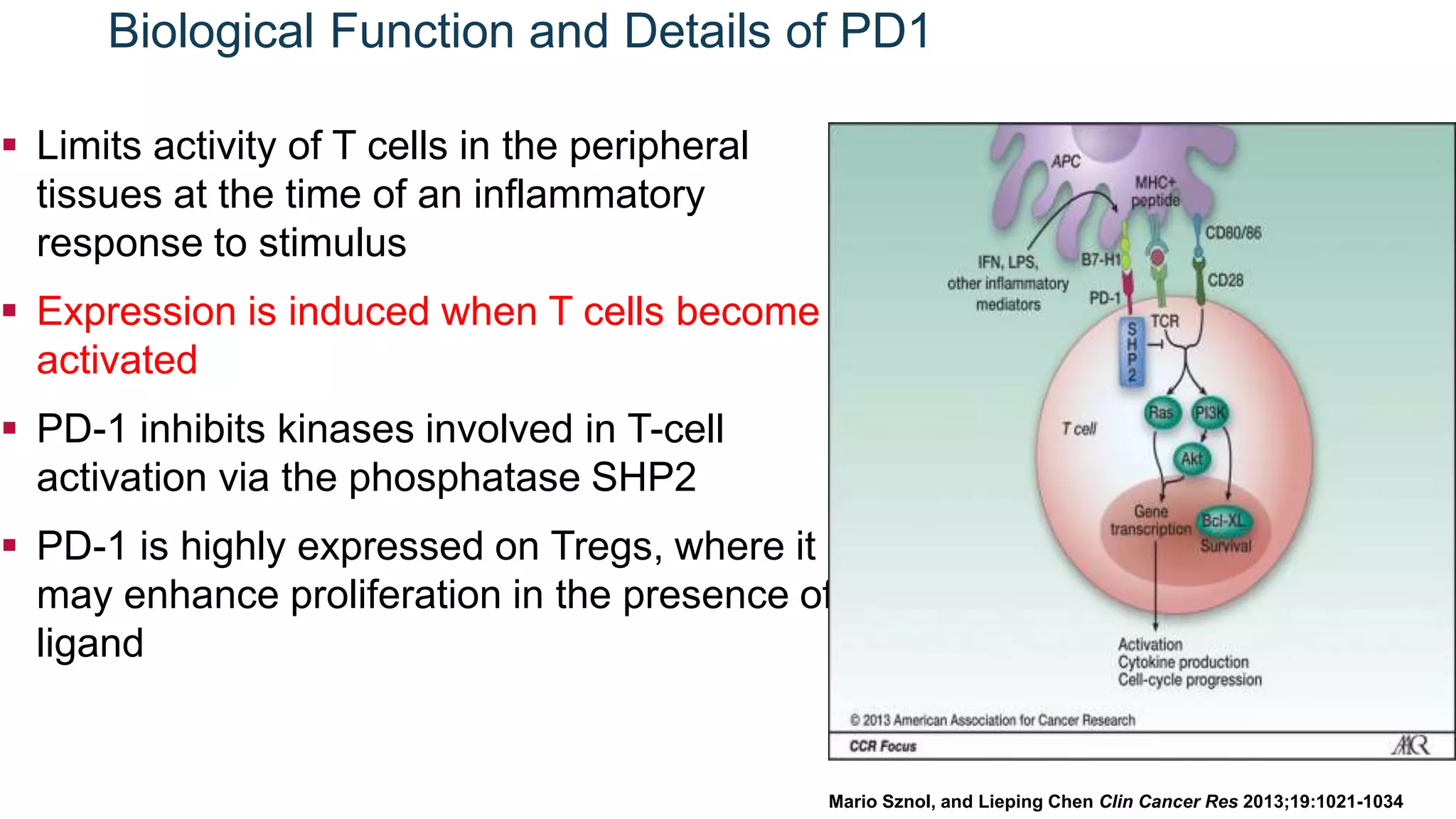

Immunological checkpoints and cancer immunotherapy were reviewed. Immune checkpoint inhibitors like anti-CTLA-4 and anti-PD-1/PD-L1 antibodies can activate the immune system against cancer by blocking inhibitory signals to T cells. Clinical trials show these drugs produce durable responses in various cancers like melanoma, lung cancer, and Merkel cell carcinoma. Combining different immunotherapies or with other treatments may help more patients by overcoming resistance. Ongoing research aims to better understand combination approaches and biomarkers of response.

![Day, Monjazeb, Sharon, Ivy, Rubin, Rosner, Butler. CCR Focus, [Accepted]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/07august2017-es-170811175031/75/Immunological-Checkpoints-and-Cancer-Immunotherapy-42-2048.jpg)