The document discusses the use of differences-in-differences (DiD) methodology for estimating causal effects, specifically in the context of voter ID laws in Indiana and Georgia. It reviews assumptions, diagnostics, and introduces a new bracketing estimator to address potential confounding effects arising from selective maturation. Key findings highlight the importance of constructing appropriate control groups based on past turnout levels to improve the accuracy of causal estimates in electoral studies.

![Diff-in-Diff: Graphical Interpretation

-

6

r

r

r

r

t = 0 t = 1

E[R00]

E[R10]

E[R01]

E[R11|Z = 1]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/keelesamsi2019-191219170607/85/Causal-Inference-Opening-Workshop-Bracketing-Bounds-for-Differences-in-Differences-Methods-Luke-Keele-December-10-2019-6-320.jpg)

![Diff-in-Diff: Graphical Interpretation

-

6

r

r

r

r

t = 0 t = 1

E[R00]

E[R10]

E[R01]

E[R11|Z = 1]

b](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/keelesamsi2019-191219170607/85/Causal-Inference-Opening-Workshop-Bracketing-Bounds-for-Differences-in-Differences-Methods-Luke-Keele-December-10-2019-7-320.jpg)

![Diff-in-Diff: Graphical Interpretation

-

6

r

r

r

r

t = 0 t = 1

E[R00]

E[R10]

E[R01]

E[R11|Z = 1]

bE[R11|Z = 0]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/keelesamsi2019-191219170607/85/Causal-Inference-Opening-Workshop-Bracketing-Bounds-for-Differences-in-Differences-Methods-Luke-Keele-December-10-2019-8-320.jpg)

![Diff-in-Diff: Graphical Interpretation

-

6

r

r

r

r

t = 0 t = 1

E[R00]

E[R10]

E[R01]

E[R11|Z = 1]

bE[R11|Z = 0]

6

?

Treatment Effect](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/keelesamsi2019-191219170607/85/Causal-Inference-Opening-Workshop-Bracketing-Bounds-for-Differences-in-Differences-Methods-Luke-Keele-December-10-2019-9-320.jpg)

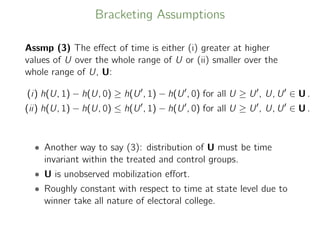

![Bracketing Assumptions

Assmp. (1) The within group distrbutions of U are stochastically

ordered:

U|G = lc U|G = t U|G = uc ,

meaning that

E[f (U)|G = lc] ≤ E[f (U)|G = t] ≤ E[f (U)|G = uc] for any

bounded, increasing function f .](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/keelesamsi2019-191219170607/85/Causal-Inference-Opening-Workshop-Bracketing-Bounds-for-Differences-in-Differences-Methods-Luke-Keele-December-10-2019-42-320.jpg)

![Bracketing Assumptions

Assmp. (1) The within group distrbutions of U are stochastically

ordered:

U|G = lc U|G = t U|G = uc ,

meaning that

E[f (U)|G = lc] ≤ E[f (U)|G = t] ≤ E[f (U)|G = uc] for any

bounded, increasing function f .

• In words: Higher values of U correspond to higher outcomes.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/keelesamsi2019-191219170607/85/Causal-Inference-Opening-Workshop-Bracketing-Bounds-for-Differences-in-Differences-Methods-Luke-Keele-December-10-2019-43-320.jpg)

![Bracketing Assumptions

Assmp. (1) The within group distrbutions of U are stochastically

ordered:

U|G = lc U|G = t U|G = uc ,

meaning that

E[f (U)|G = lc] ≤ E[f (U)|G = t] ≤ E[f (U)|G = uc] for any

bounded, increasing function f .

• In words: Higher values of U correspond to higher outcomes.

• U is unobserved mobilization effort.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/keelesamsi2019-191219170607/85/Causal-Inference-Opening-Workshop-Bracketing-Bounds-for-Differences-in-Differences-Methods-Luke-Keele-December-10-2019-44-320.jpg)

![Bracketing Assumptions

Assmp. (1) The within group distrbutions of U are stochastically

ordered:

U|G = lc U|G = t U|G = uc ,

meaning that

E[f (U)|G = lc] ≤ E[f (U)|G = t] ≤ E[f (U)|G = uc] for any

bounded, increasing function f .

• In words: Higher values of U correspond to higher outcomes.

• U is unobserved mobilization effort.

• Higher values of U likely lead to higher levels of turnout.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/keelesamsi2019-191219170607/85/Causal-Inference-Opening-Workshop-Bracketing-Bounds-for-Differences-in-Differences-Methods-Luke-Keele-December-10-2019-45-320.jpg)

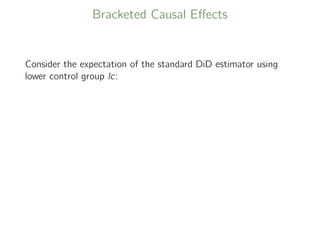

![Bracketed Causal Effects

Consider the expectation of the standard DiD estimator using

lower control group lc:

E ˆβdd.lc =

β + (E[h(U, 1) − h(U, 0)|G = t]) − (E[h(U, 1) − h(U, 0)|G = lc])](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/keelesamsi2019-191219170607/85/Causal-Inference-Opening-Workshop-Bracketing-Bounds-for-Differences-in-Differences-Methods-Luke-Keele-December-10-2019-52-320.jpg)

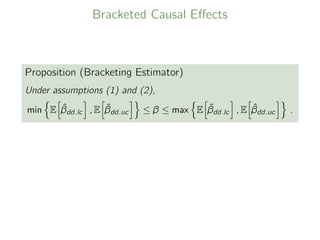

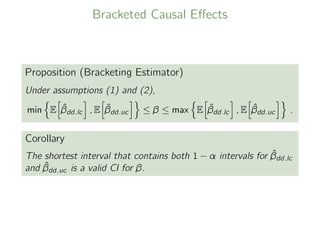

![Bracketed Causal Effects

Consider the expectation of the standard DiD estimator using

lower control group lc:

E ˆβdd.lc =

β + (E[h(U, 1) − h(U, 0)|G = t]) − (E[h(U, 1) − h(U, 0)|G = lc])

Similar logic yields,

E ˆβdd.uc =

β +(E[h(U, 1) − h(U, 0)|G = t])−(E[h(U, 1) − h(U, 0)|G = uc])](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/keelesamsi2019-191219170607/85/Causal-Inference-Opening-Workshop-Bracketing-Bounds-for-Differences-in-Differences-Methods-Luke-Keele-December-10-2019-53-320.jpg)

![DID Bracketing Estimates for Indiana

2008

DID Point Estimate 95% CI

Lower Control Group 4.4 [3.3, 5.4]

Upper Control Group 5.7 [4.2, 7.1]

Bounds [3.3, 7.1]

2012

DID Point Estimate 95% CI

Lower Control Group 5.9 [3.1, 8.6]

Upper Control Group 4.3 [3.3, 5.4]

Bounds [3.1, 8.6]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/keelesamsi2019-191219170607/85/Causal-Inference-Opening-Workshop-Bracketing-Bounds-for-Differences-in-Differences-Methods-Luke-Keele-December-10-2019-63-320.jpg)

![DID Bracketing Estimates for Georgia

2008

DID Point Estimate 95% CI

Lower Control Group 9.8 [6.5, 13.1]

Upper Control Group 7.6 [6.3, 8.9]

Bounds [6.3, 13.1]

2012

DID Point Estimate 95% CI

Lower Control Group 13.4 [12.0, 14.8]

Upper Control Group 8.5 [6.7, 10.4]

Bounds [6.7, 14.8]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/keelesamsi2019-191219170607/85/Causal-Inference-Opening-Workshop-Bracketing-Bounds-for-Differences-in-Differences-Methods-Luke-Keele-December-10-2019-64-320.jpg)

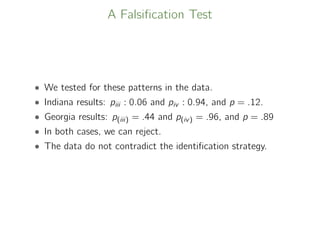

![A Falsification Test

The first pattern is

E[Y (−1)

|Zi = 1] − E[Y (−2)

|Zi = 1]

E[Y (−1)

|Zi = 0] − E[Y (−2)

|Zi = 0]

βuc,−t = E[Y (−1)

|Zi = 1] − E[Y (−2)

|Zi = 1] −

E[Y (−1)

|Zi = 0] − E[Y (−2)

|Zi = 0]

Test as: H(iii)[a] : βuc,−t 0 using p(iii)[a]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/keelesamsi2019-191219170607/85/Causal-Inference-Opening-Workshop-Bracketing-Bounds-for-Differences-in-Differences-Methods-Luke-Keele-December-10-2019-77-320.jpg)

![A Falsification Test

The second pattern is

E[Y (−1)

|Di = 1] − E[Y (−2)

|Di = 1]

E[Y (−1)

|Di = 0] − E[Y (−2)

|Di = 0] .

Test as: H(iii)[b] : βlc,−t 0 using p(iii)[b]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/keelesamsi2019-191219170607/85/Causal-Inference-Opening-Workshop-Bracketing-Bounds-for-Differences-in-Differences-Methods-Luke-Keele-December-10-2019-78-320.jpg)

![A Falsification Test

The third pattern is:

E[Y (−1)

|Zi = 1] − E[Y (−2)

|Zi = 1]

E[Y (−1)

|Zi = 0] − E[Y (−2)

|Zi = 0]

Test: H(iv)[a] : βuc,−t 0 using p(iv)[a]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/keelesamsi2019-191219170607/85/Causal-Inference-Opening-Workshop-Bracketing-Bounds-for-Differences-in-Differences-Methods-Luke-Keele-December-10-2019-79-320.jpg)

![A Falsification Test

The fourth pattern is:

E[Y (−1)

|Di = 1] − E[Y (−2)

|Di = 1]

E[Y (−1)

|Di = 0] − E[Y (−2)

|Di = 0]

Test: H(iv)[a] : βul,−t 0 using p(iv)[b]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/keelesamsi2019-191219170607/85/Causal-Inference-Opening-Workshop-Bracketing-Bounds-for-Differences-in-Differences-Methods-Luke-Keele-December-10-2019-80-320.jpg)

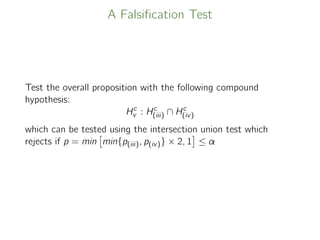

![A Falsification Test

Test Hc

(iii) with p(iii) = max{p(iii)[a], p(iii)[b]}

Test Hc

(iv) with p(iv) = max{p(iii)[a], p(iii)[b]}](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/keelesamsi2019-191219170607/85/Causal-Inference-Opening-Workshop-Bracketing-Bounds-for-Differences-in-Differences-Methods-Luke-Keele-December-10-2019-81-320.jpg)

![Sensitivity Analysis Bounds

The sensitivity bounds are:

LBsens = min[(τCIBBlb

−db2, τCIBBlb

−da), (τCIBBlb

−db, τCIBBlb

−da2)]

UBsens = max[(τCIBBub

− (−db2), τCIBBub

− (−da)),

(τCIBBub

− (−db), τCIBBub

− (−da2))]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/keelesamsi2019-191219170607/85/Causal-Inference-Opening-Workshop-Bracketing-Bounds-for-Differences-in-Differences-Methods-Luke-Keele-December-10-2019-93-320.jpg)

![Sensitivity Analysis

Table: Sensitivity Analysis for Indiana

2008

DID Bracketing Bounds [3.3, 7.1]

Sensitivity Analysis Bounds [1.7, 12.0]

2012

DID Bracketing Bounds [3.1, 8.6]

Sensitivity Analysis Bounds [0.0, 18.0]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/keelesamsi2019-191219170607/85/Causal-Inference-Opening-Workshop-Bracketing-Bounds-for-Differences-in-Differences-Methods-Luke-Keele-December-10-2019-94-320.jpg)

![Sensitivity Analysis

Table: Sensitivity Analysis for Georgia

2008

DID Bracketing Bounds [6.3, 13.1]

Sensitivity Analysis Bounds [1.2, 13.6]

2012

DID Bracketing Bounds [6.7, 14.8]

Sensitivity Analysis Bounds [-1.2, 15.0]](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/keelesamsi2019-191219170607/85/Causal-Inference-Opening-Workshop-Bracketing-Bounds-for-Differences-in-Differences-Methods-Luke-Keele-December-10-2019-95-320.jpg)