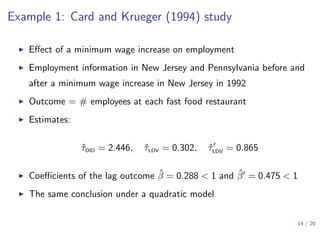

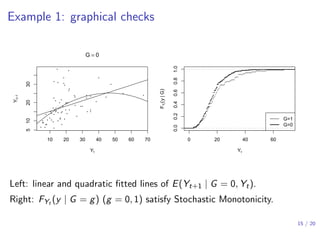

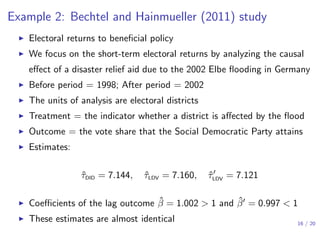

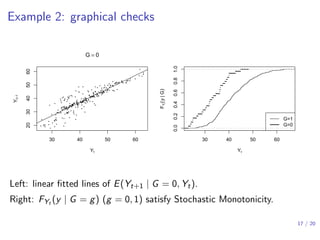

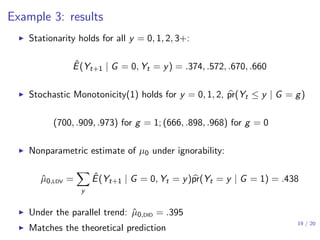

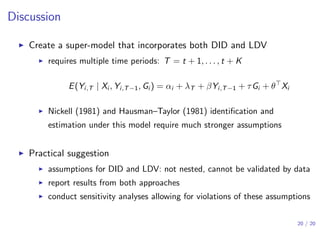

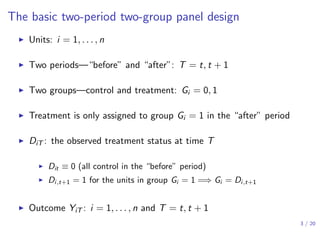

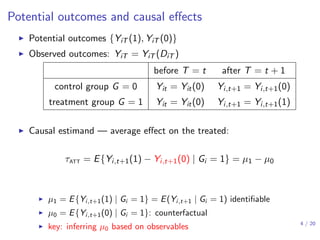

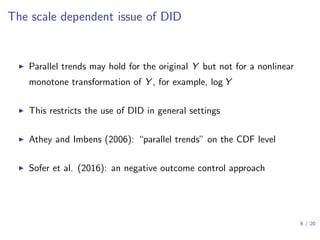

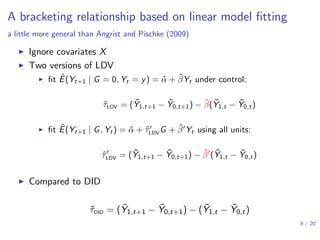

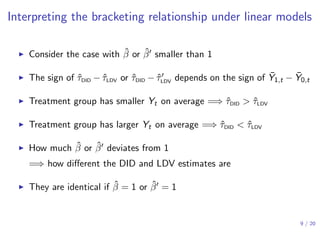

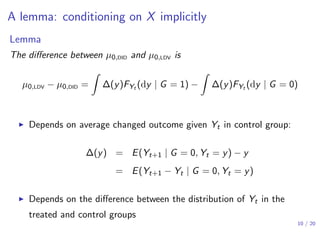

This document discusses the relationship between difference-in-differences (DiD) and lagged-dependent-variable (LDV) adjustment methods in causal inference. It presents a framework for identifying causal effects and highlights the importance of the assumptions underlying these methodologies, including parallel trends and stationarity. The findings suggest conditions under which DiD estimates may overestimate or underestimate true causal effects, with examples illustrating these concepts in real-world studies.

![Difference-in-differences (DID)

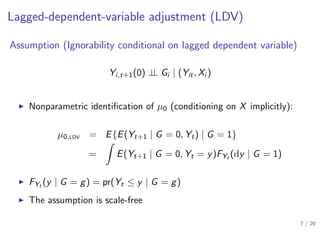

Assumption (Parallel trends conditioning on covariates Xi )

E{Yi,t+1(0) − Yi,t(0) | Xi , Gi = 1} = E{Yi,t+1(0) − Yi,t(0) | Xi , Gi = 0}

▶ Nonparametric identification of µ0 = E{Yi,t+1(0) | Gi = 1}

µ0,DID = E [E{Yit (0) | Xi , Gi = 1} + E{Yi,t+1(0) − Yit (0) | Xi , Gi = 0} | Gi = 1]

= E(Yit | Gi = 1) + E{E(Yi,t+1 − Yit | Xi , Gi = 0) | Gi = 1}

▶ Without covariates — difference-in-difference

▶ nonparametric identification:

µ0 = E(Yit | Gi = 1) + E(Yi,t+1 | Gi = 0) − E(Yit | Gi = 0)

▶ moment estimator: ˆτDID = ( ¯Y1,t+1 − ¯Y1,t) − ( ¯Y0,t+1 − ¯Y0,t)

5 / 20](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/didldvpresentation2019samsi-191219170825/85/Causal-Inference-Opening-Workshop-A-Bracketing-Relationship-between-Difference-in-Differences-and-Lagged-Dependent-Variable-Adjustment-Peng-Ding-December-11-2019-5-320.jpg)

![Interpretations of the theorem

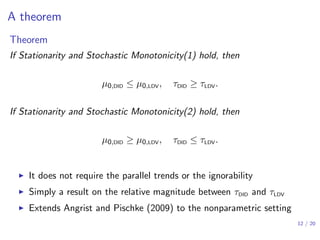

▶ Under Stationarity and Stochastic Monotonicity(1),

τDID ≥ τLDV

▶ Both of them can be biased for the true causal effect τATT

▶ τDID ≥ τLDV ≥ τATT =⇒ τDID over-estimates τATT more than τLDV

▶ τATT ≥ τDID ≥ τLDV =⇒ τLDV under-estimates τATT more than τDID

▶ τDID ≥ τATT ≥ τLDV =⇒ τDID and τLDV are the upper and lower bounds

▶ In the last case, [τLDV, τDID] bracket the true causal effect

▶ Analogous results under Stationarity and Stochastic Monotonicity(2)

13 / 20](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/didldvpresentation2019samsi-191219170825/85/Causal-Inference-Opening-Workshop-A-Bracketing-Relationship-between-Difference-in-Differences-and-Lagged-Dependent-Variable-Adjustment-Peng-Ding-December-11-2019-13-320.jpg)