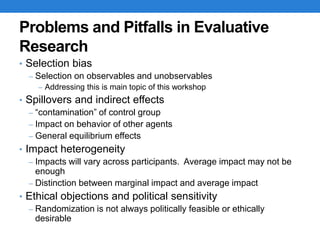

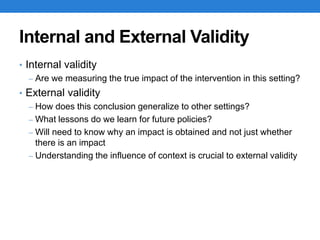

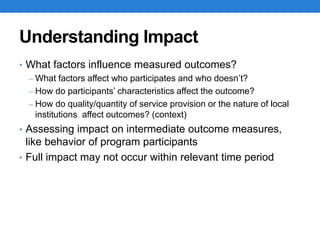

This document discusses causal inference and program evaluation. It notes that evaluating programs requires estimating the counterfactual outcome for participants in the absence of the program, which is difficult. Common problems in evaluation include selection bias if participants differ from non-participants in unobserved ways, spillover effects, and impact heterogeneity. Internal validity assesses if the true impact is measured, while external validity examines generalizability. Estimating average treatment effects requires addressing non-random selection into programs.

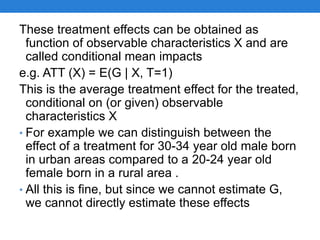

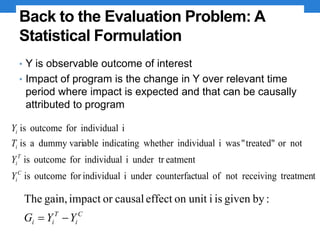

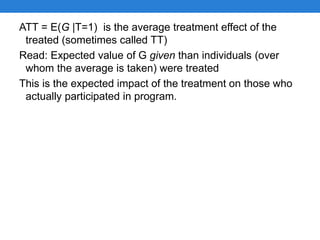

![ATU = E(G | T=0) is the average treatment effect on the

untreated (sometimes called TU)

This is the expected impact of the treatment on those who

did not participate.

Thus the average treatment effect for a random individual

in the population is given by

ATE = ATT * Pr[T=1] + ATU * Pr[T=0]

where Pr[T=1] is the probability of being treated.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/erftrainingjuly2016day1fundamentalproblemofcausalinferencera-160801103357/85/Causal-Inference-and-Program-Evaluation-11-320.jpg)