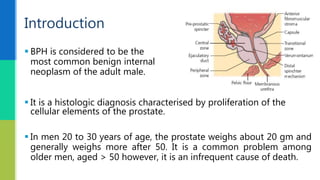

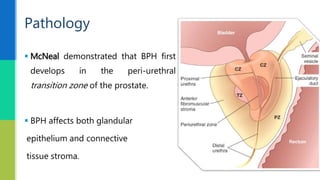

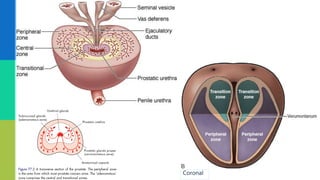

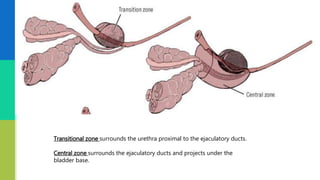

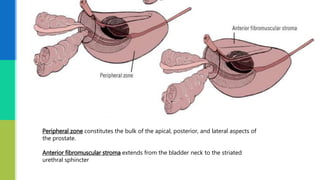

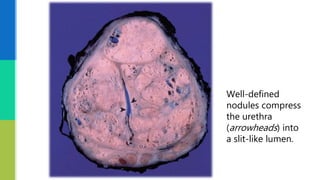

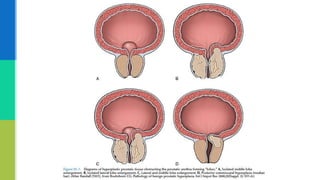

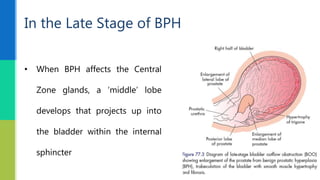

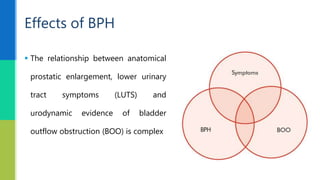

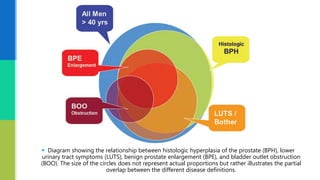

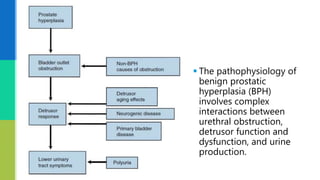

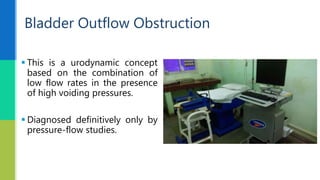

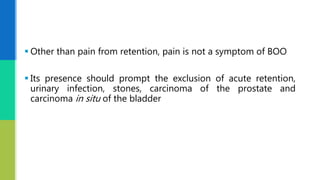

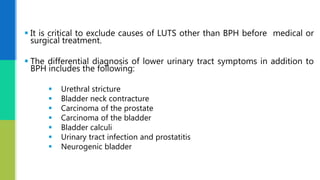

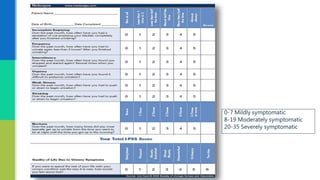

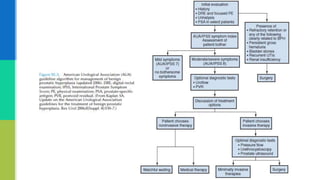

This document provides an overview of benign prostatic hyperplasia (BPH) including its etiology, pathology, clinical findings, and investigation. It notes that BPH begins as microscopic nodules in the transitional zone of the prostate that can grow and compress surrounding tissue. Common symptoms include urinary frequency, urgency, and nocturia. Evaluation involves assessment of lower urinary tract symptoms, digital rectal exam, urinalysis, post-void residual measurement, and in some cases urodynamic testing. BPH is a common condition among older men that results from changes in hormone levels and growth factors.