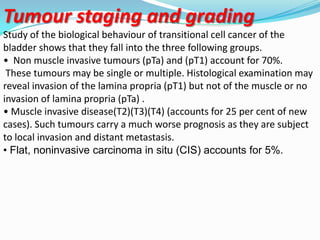

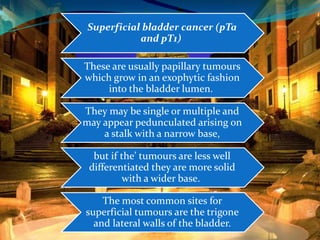

1. The majority (95%) of primary bladder tumors originate from the bladder epithelium and are transitional cell carcinoma (90%). Squamous cell carcinoma (5%) and adenocarcinoma (1-2%) can also occur.

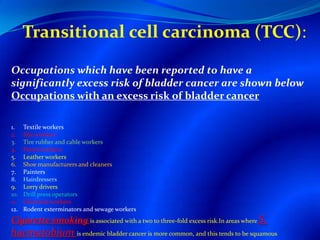

2. Risk factors for bladder cancer include occupational exposures like chemicals, smoking, and infections like Schistosomiasis.

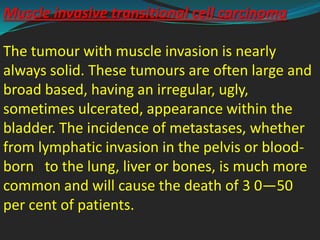

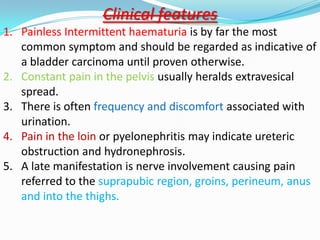

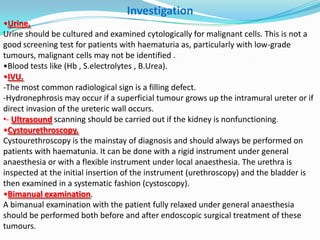

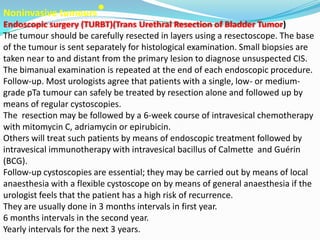

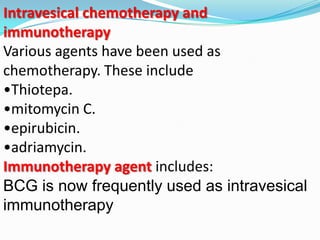

3. Evaluation involves urine cytology, cystoscopy, imaging and biopsy. Treatment depends on tumor stage and grade, ranging from transurethral resection for non-muscle invasive tumors to radical cystectomy for muscle-invasive tumors.