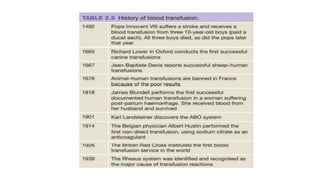

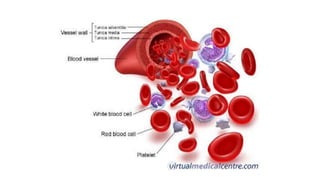

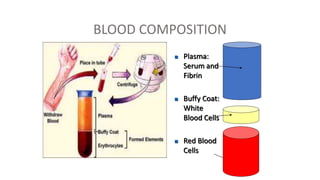

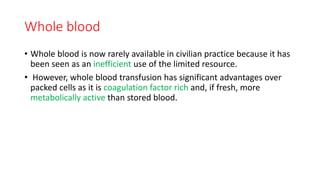

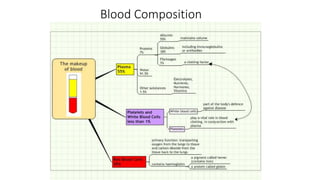

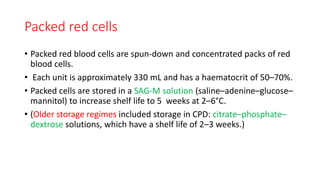

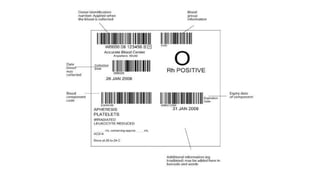

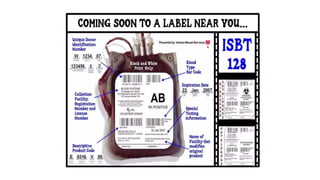

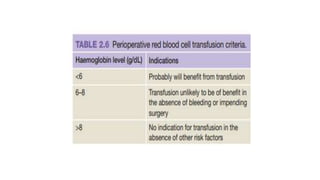

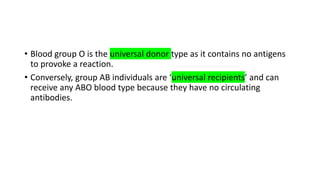

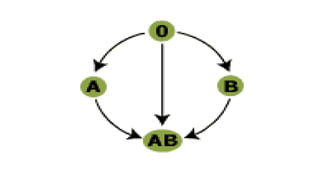

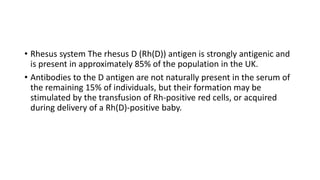

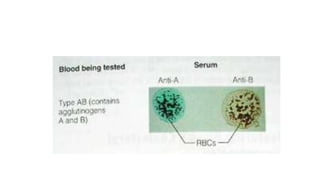

This document summarizes information about blood products and transfusion. It discusses how blood is collected from donors and tested before being separated into components like packed red blood cells, fresh frozen plasma, cryoprecipitate, and platelets. It describes the storage and uses of these components. The document also covers blood groups, cross-matching, transfusion reactions, complications of transfusion, indications for transfusion, and blood substitutes currently under investigation.