This document provides an overview of fractures and dislocations, including:

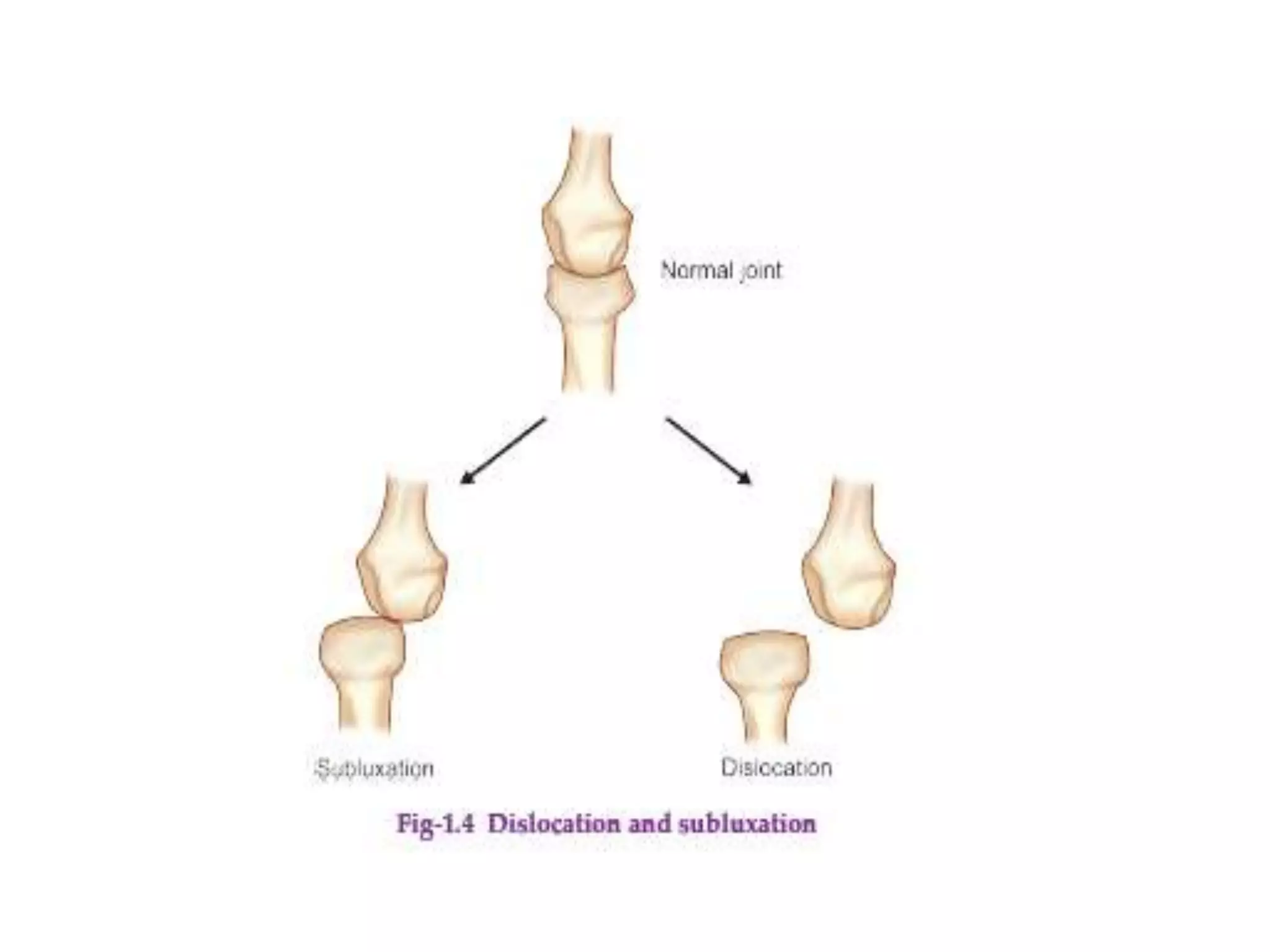

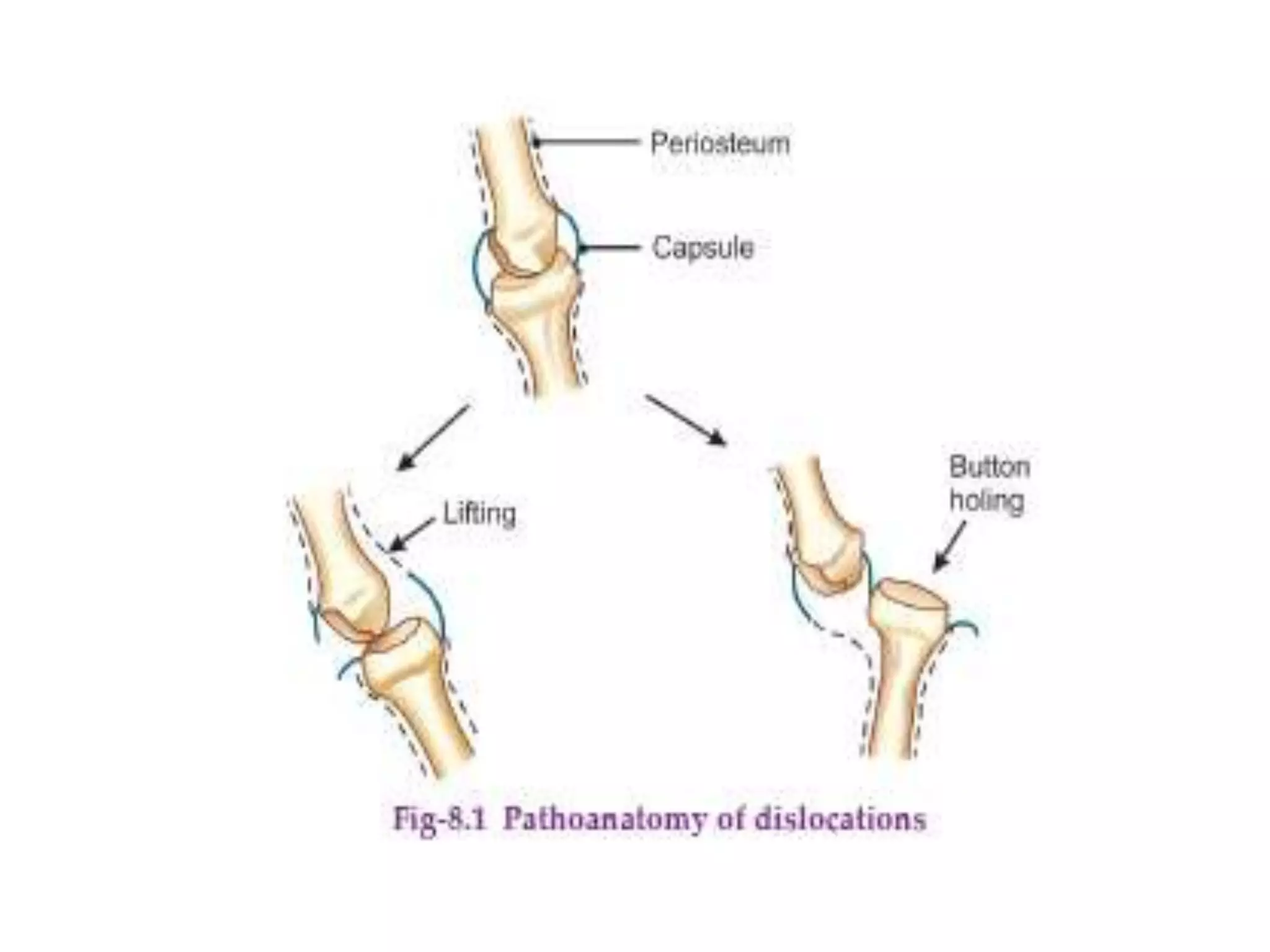

- A fracture is a break in the continuity of a bone, while a dislocation is the complete displacement of articular surfaces from one another.

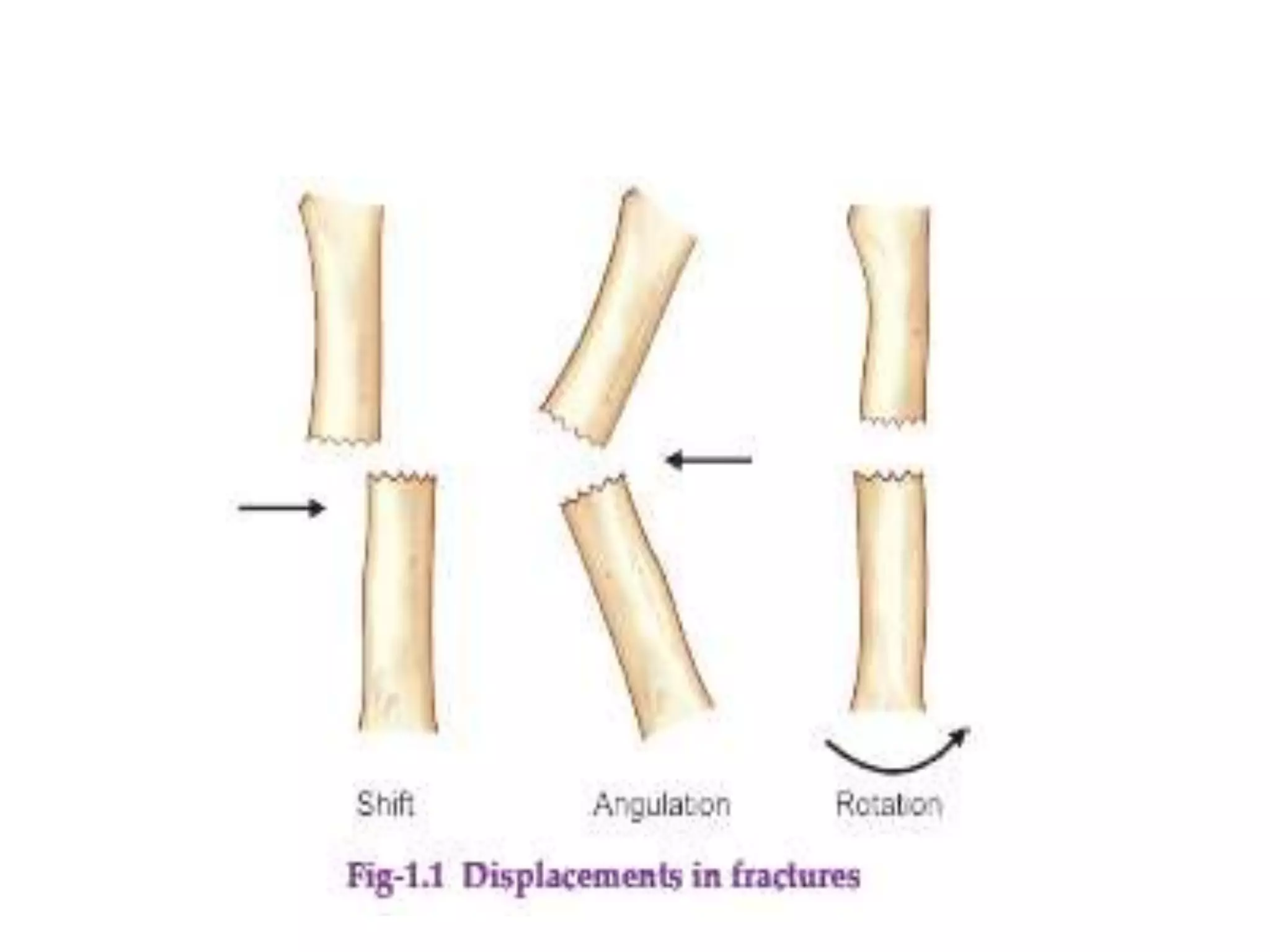

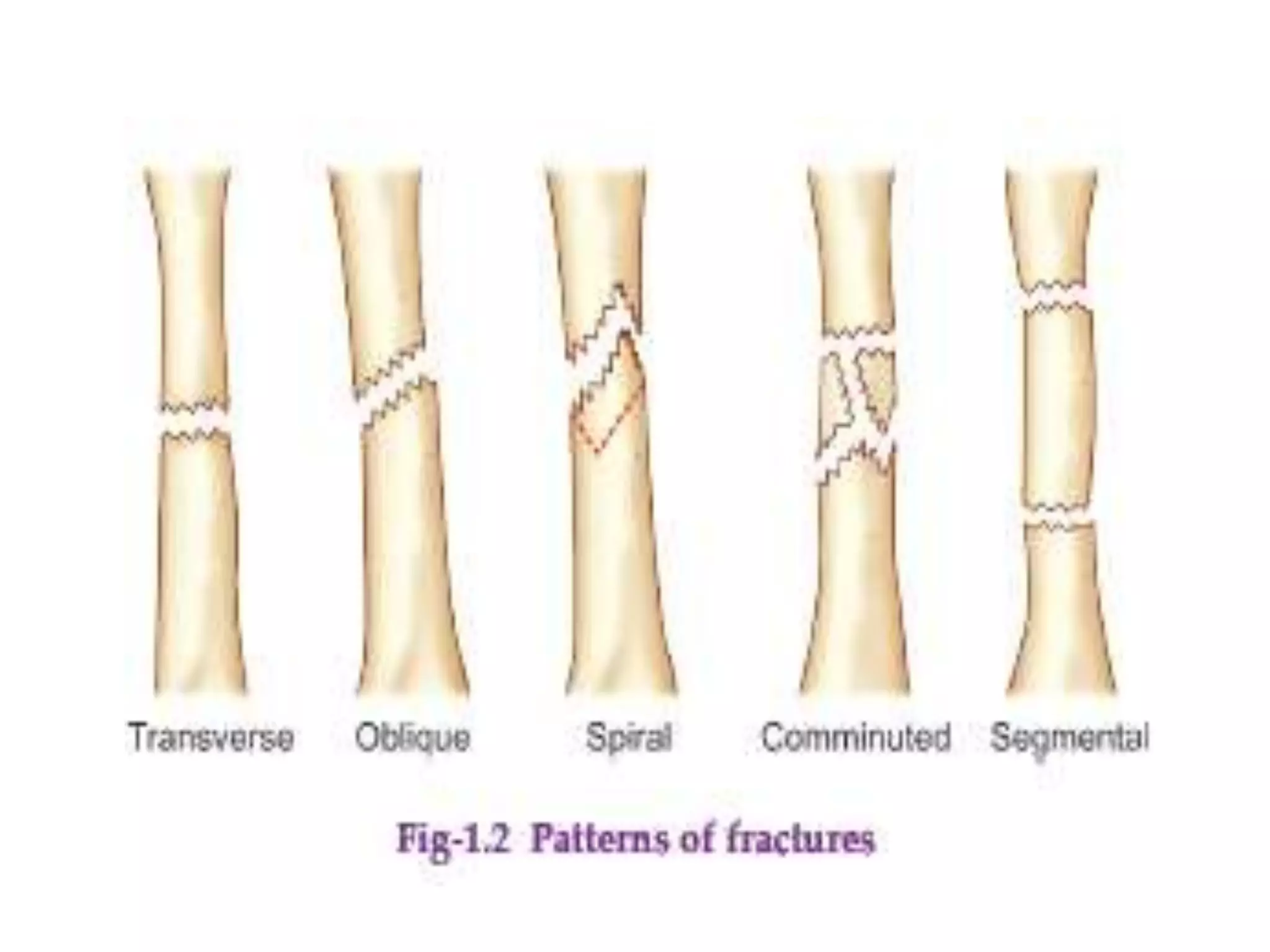

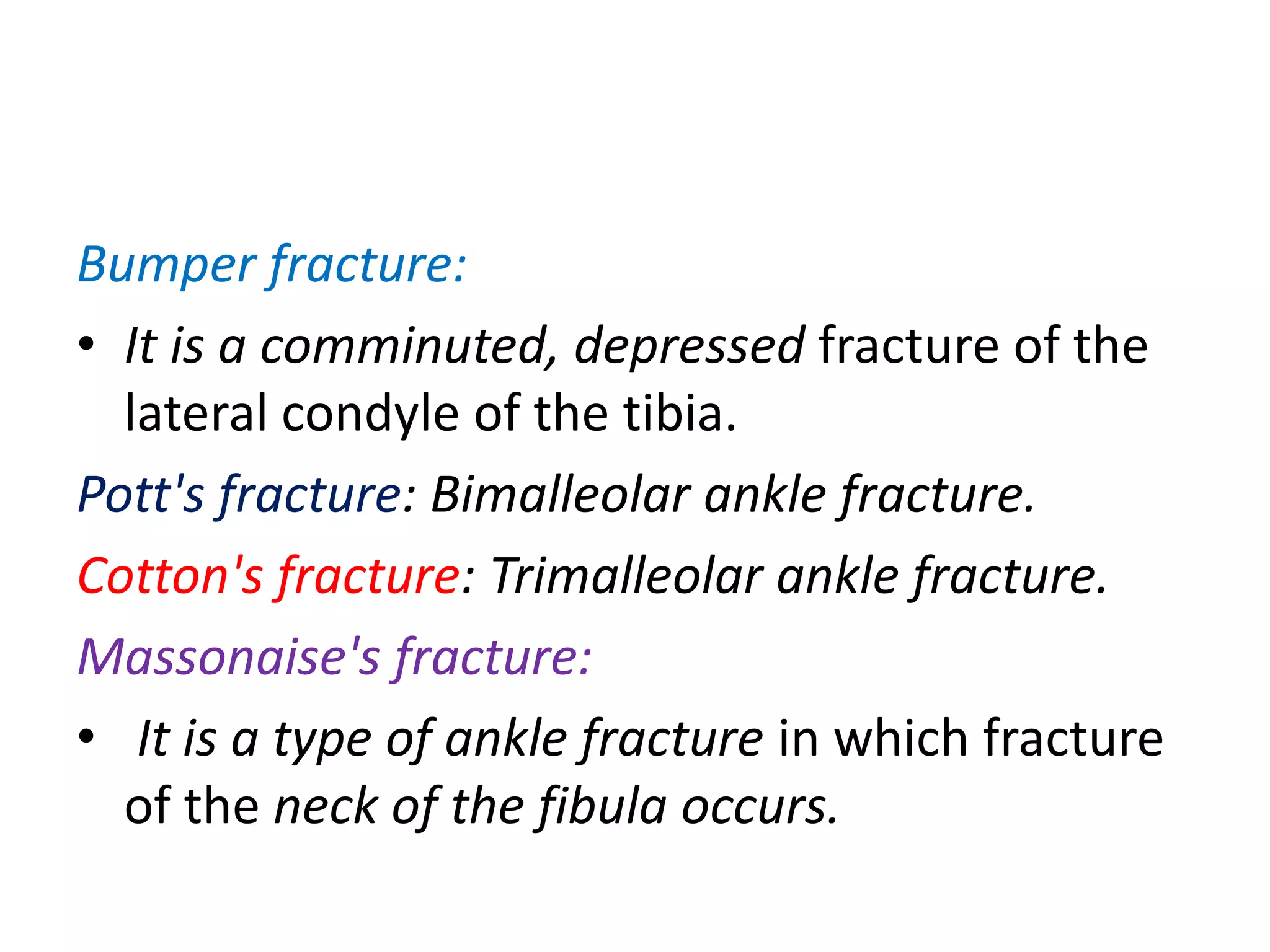

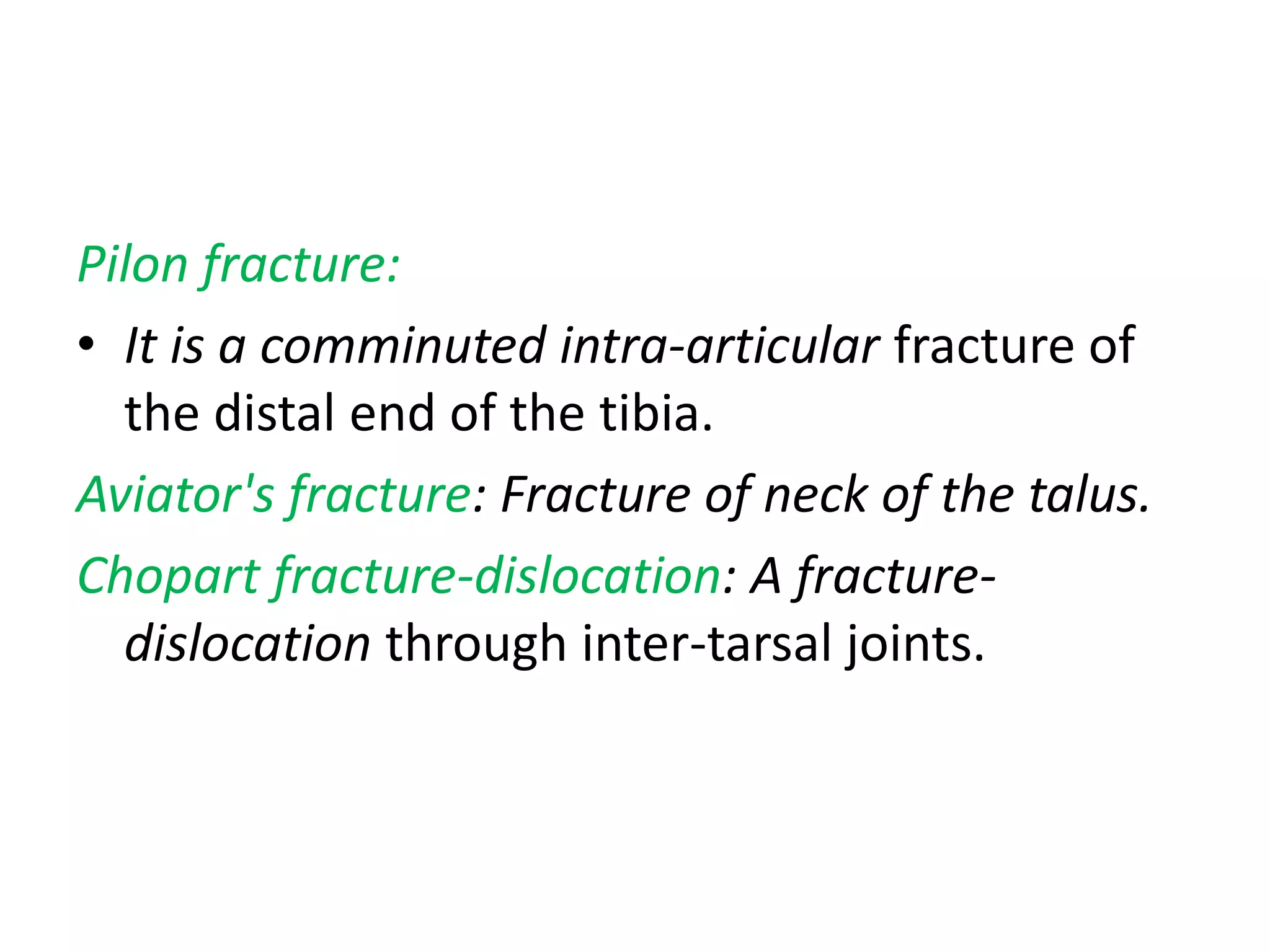

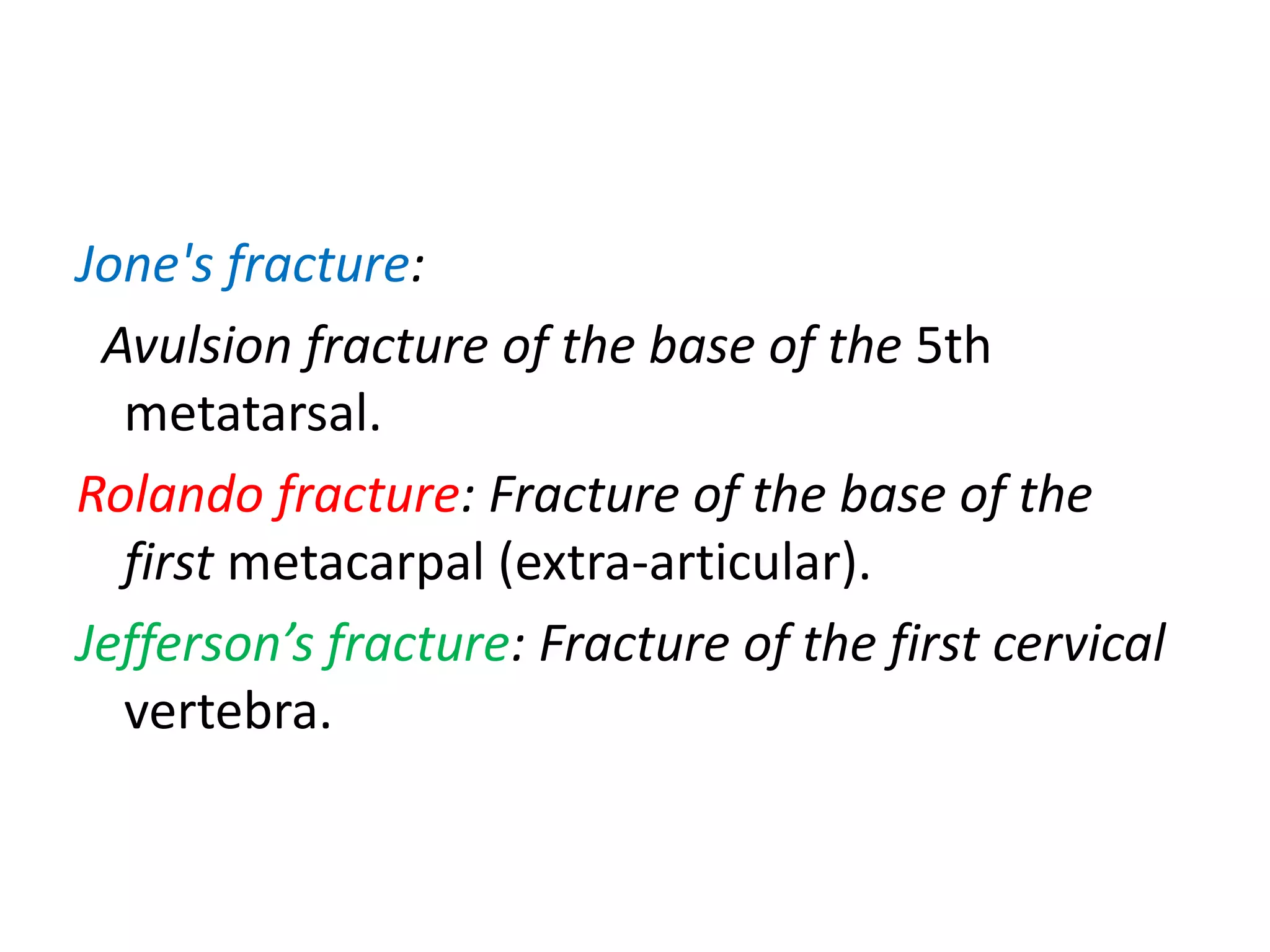

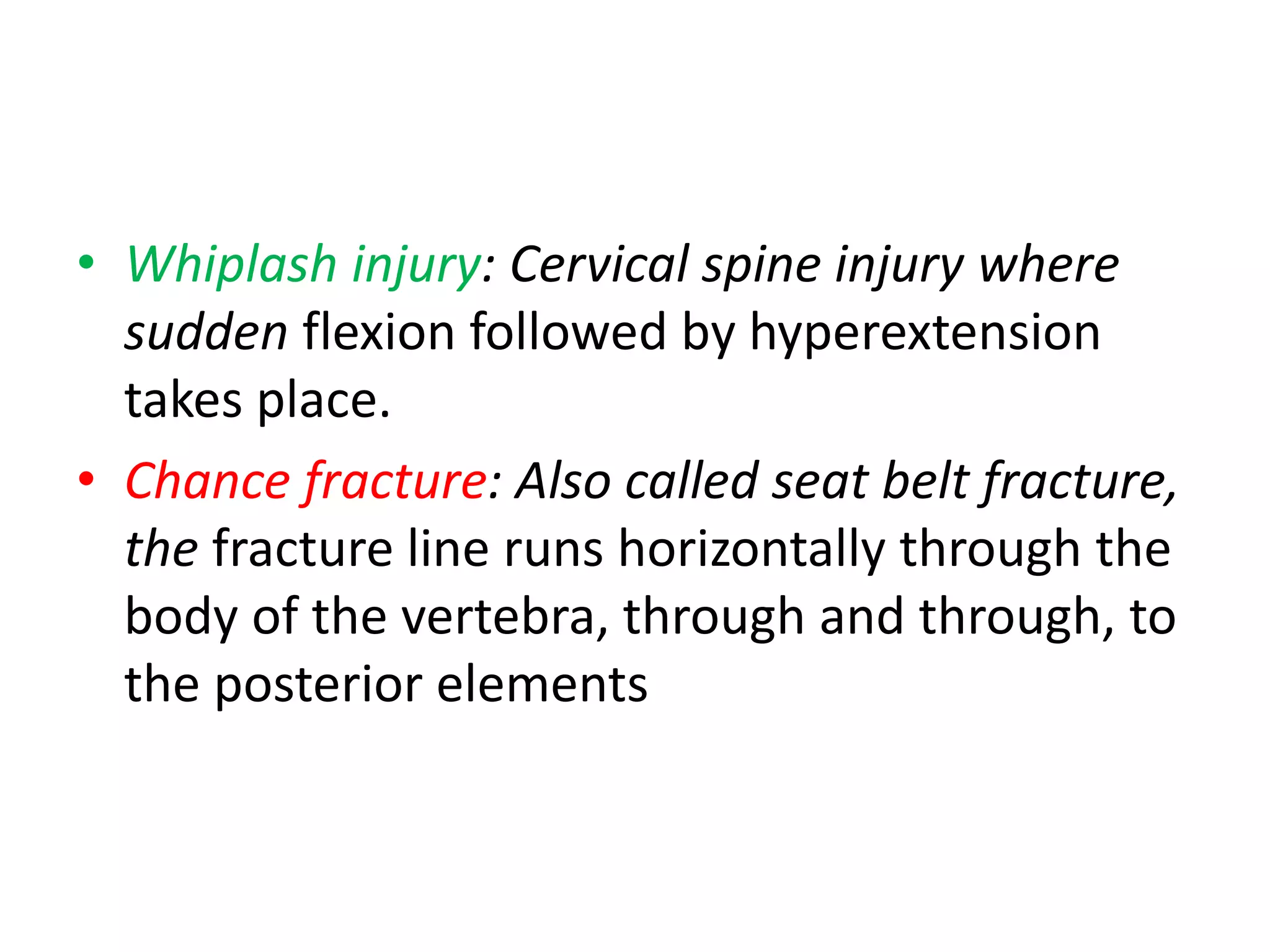

- Fractures can be classified based on etiology (traumatic, pathological, stress), displacement, relationship to external environment (closed, open), complexity of treatment (simple, complex), and pattern (transverse, oblique, etc.).

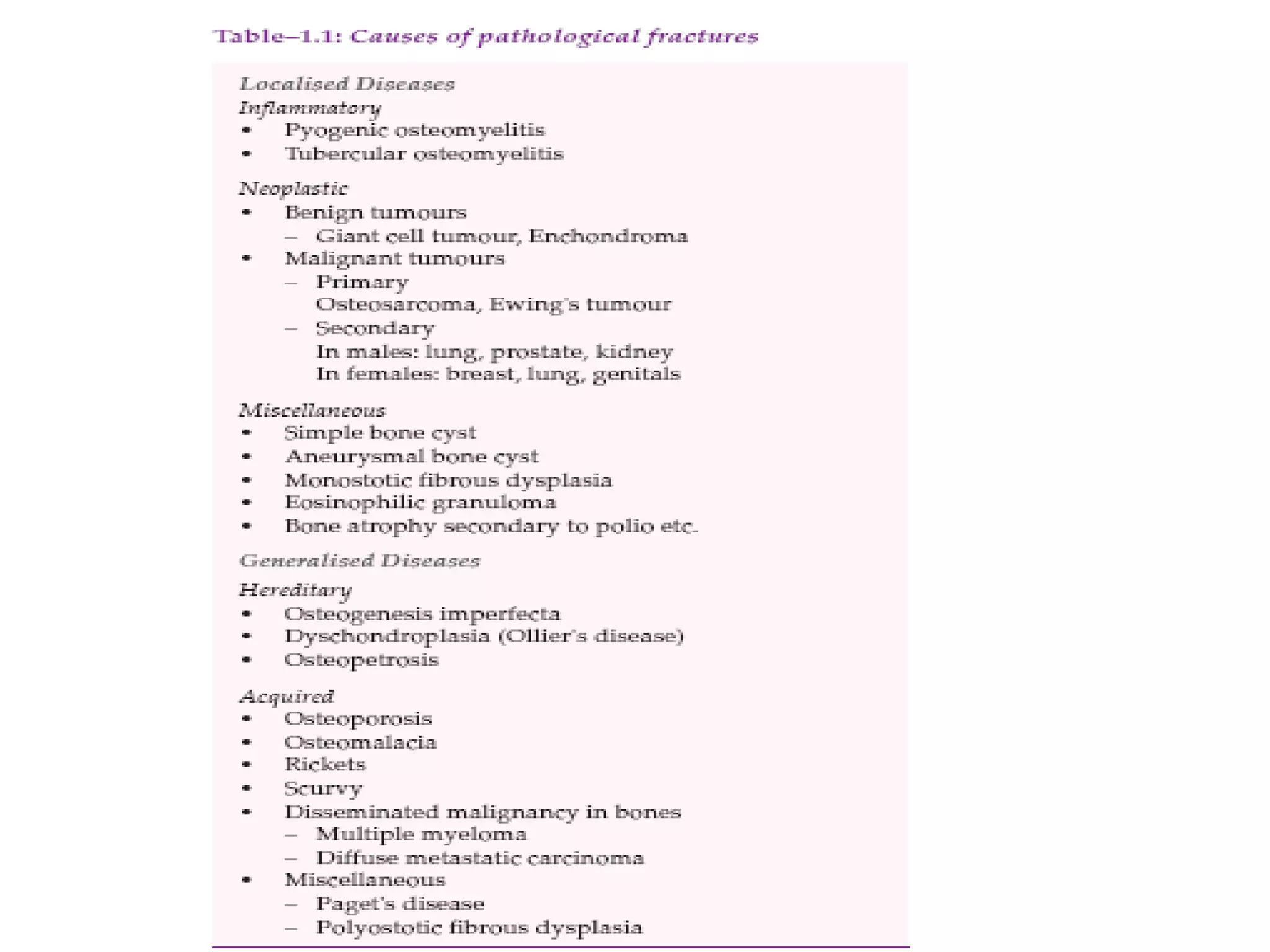

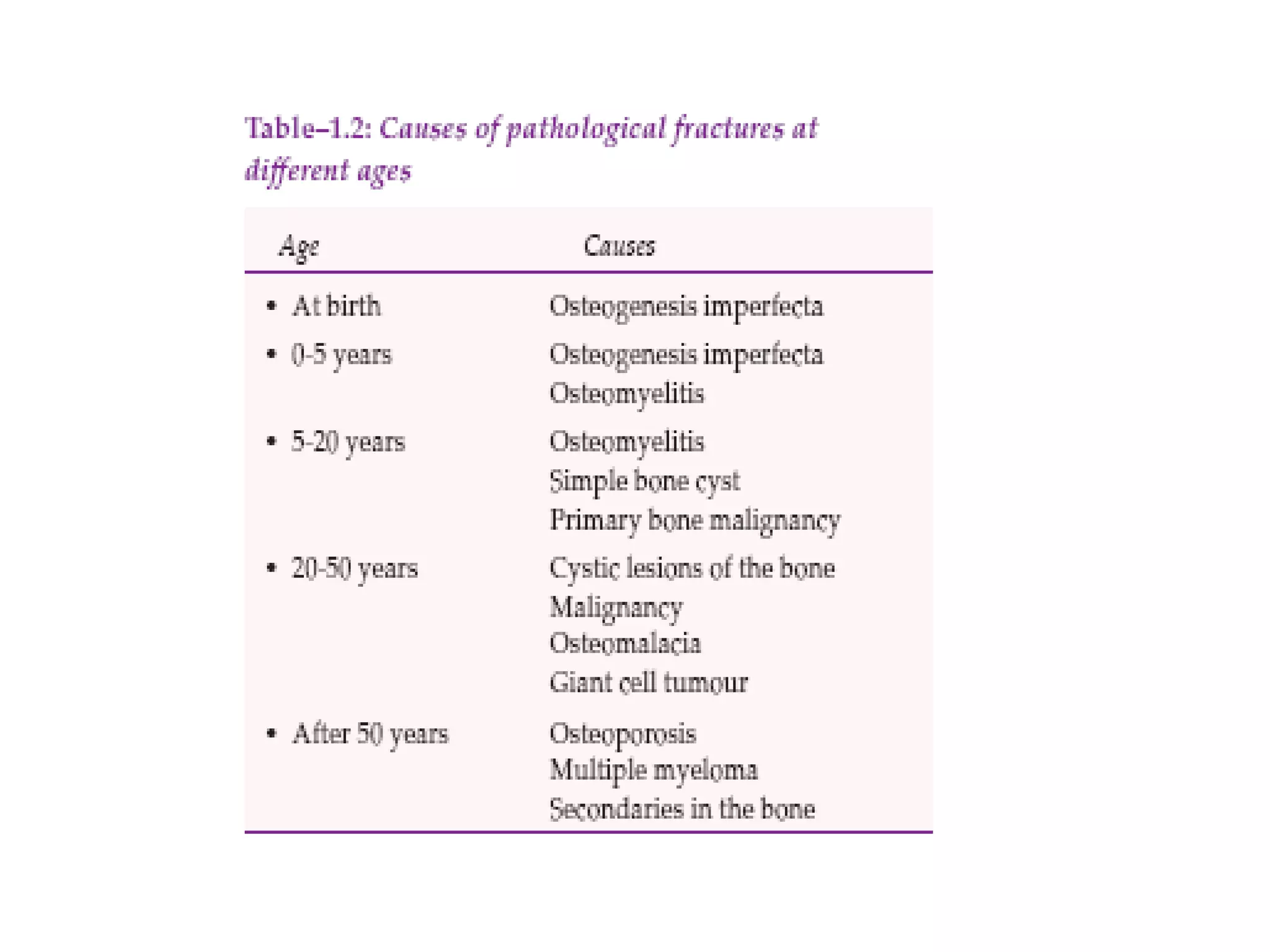

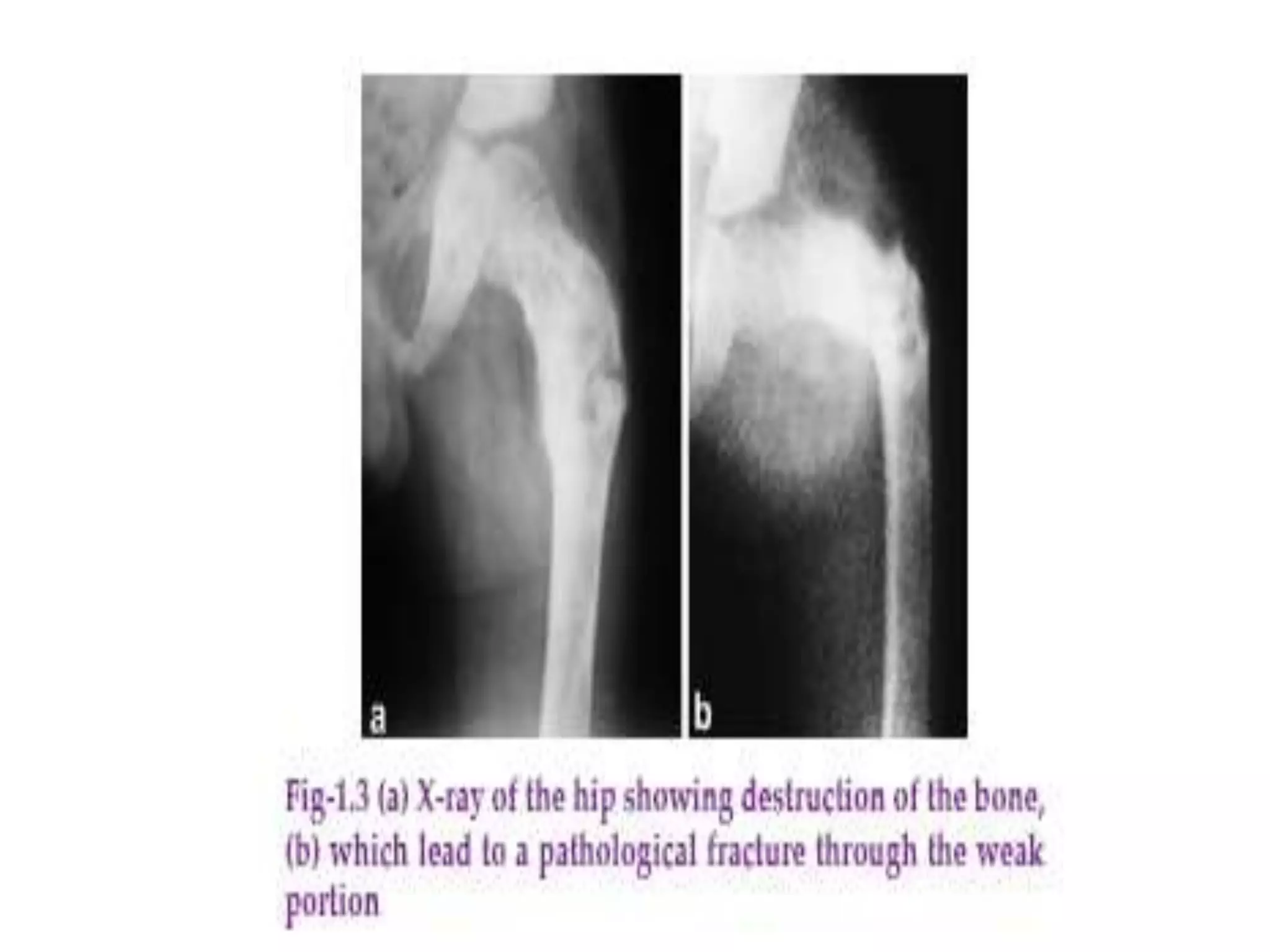

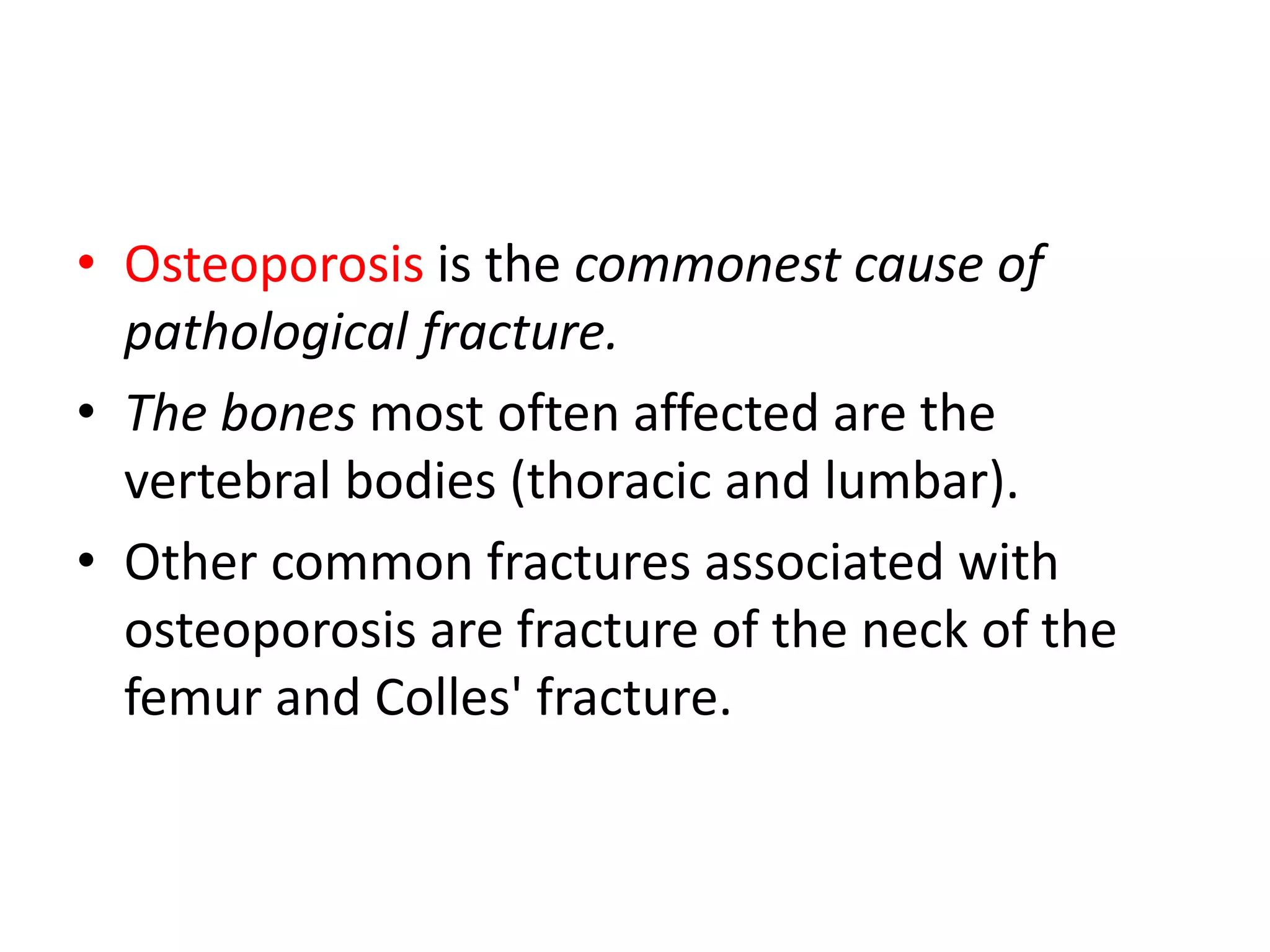

- Pathological fractures occur through weakened bone from underlying disease. Treatment involves addressing the underlying cause and stabilizing the fracture.

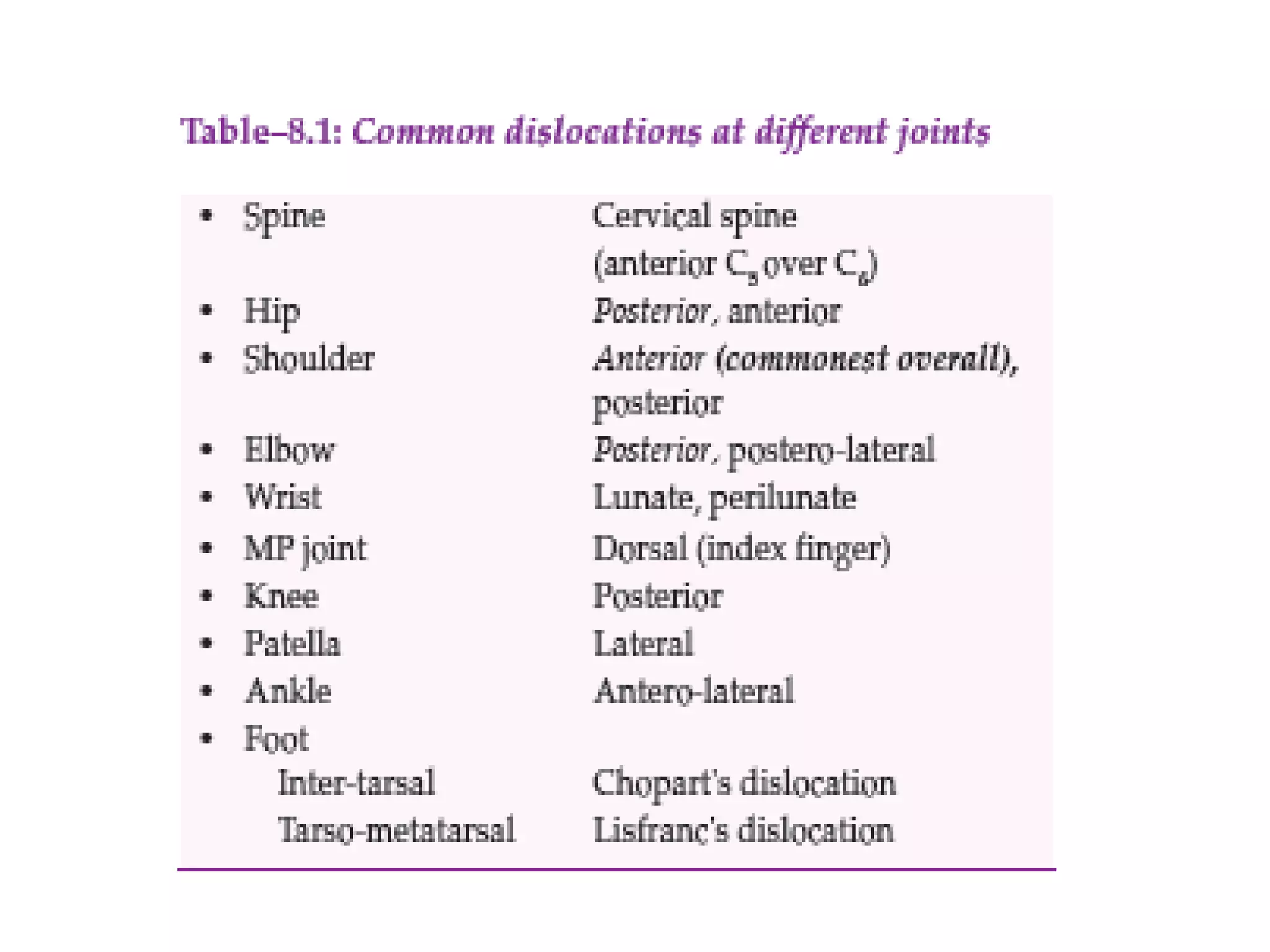

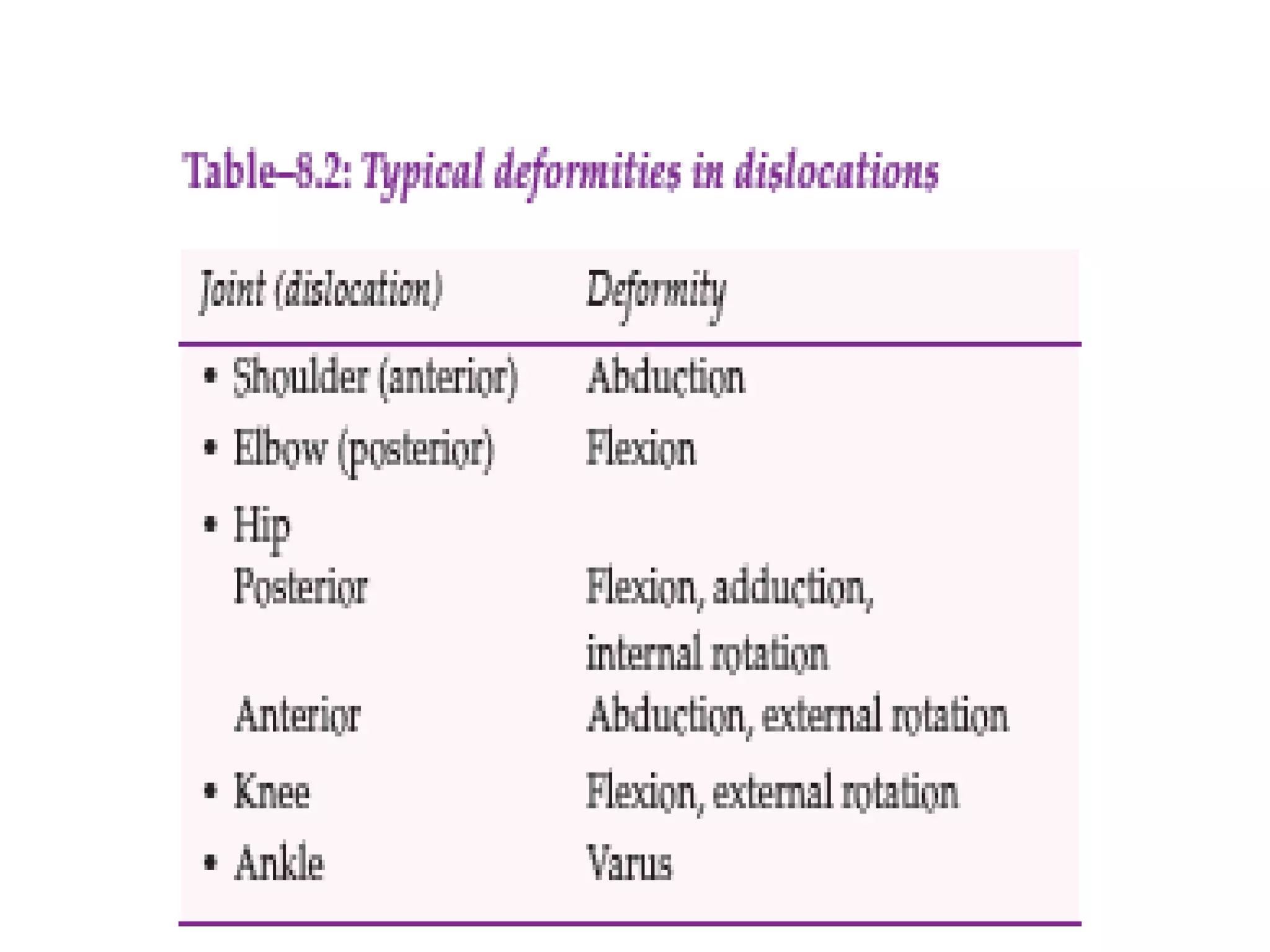

- Dislocations can cause immediate complications like neurovascular injury or long-term issues like recurrence, stiffness and arthritis.