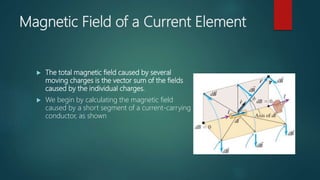

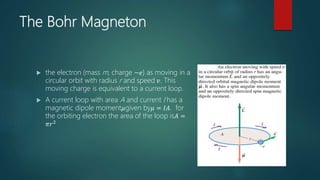

The document discusses the magnetic field created by moving charges and currents. It introduces the concept of the magnetic field created by a single moving charge (Biot-Savart law) and a current element. It then expands this to discuss how the total magnetic field is calculated by integrating these infinitesimal fields over all current elements using Ampere's law. Several examples are given to illustrate these principles, including the magnetic field around a long straight wire and how Ampere's law relates the line integral of B around a closed path to the current passing through the enclosed area. The document concludes by discussing how magnetic properties originate at the atomic level due to electron orbits and spins, defining the Bohr magneton as the fundamental unit of magnetic moment