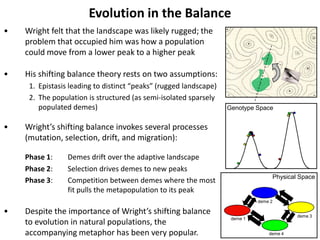

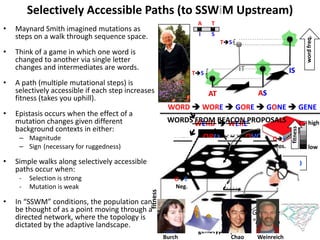

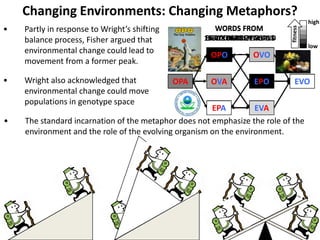

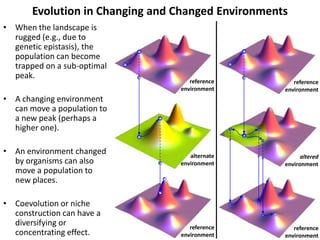

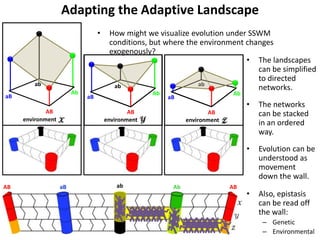

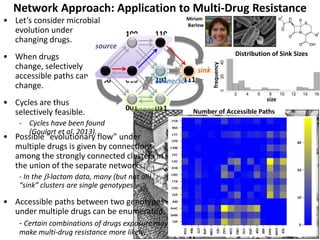

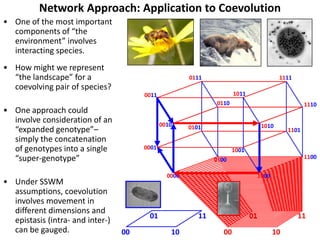

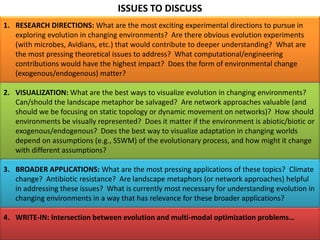

This document discusses evolution in changing environments using adaptive landscape metaphors. It describes Darwin's concept of natural selection acting on variations, Wright's shifting balance theory involving semi-isolated populations on a rugged adaptive landscape, and how environmental changes can move populations between peaks. Network representations of selectively accessible paths are introduced as alternatives to landscapes. The document explores applying these approaches to microbial evolution under changing drugs and coevolution, suggesting networked models could represent accessible evolutionary paths. It raises issues for further discussion around experimental directions, visualization techniques, broader applications, and intersections with optimization problems.

![Picking the Wright Metaphor

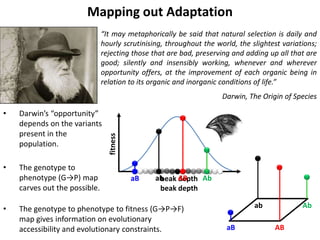

Wright

• In 1932, Sewall Wright was invited to give a non-

technical talk on his view of evolution at the sixth

International Congress of Genetics.

• Wright (1932) started with a simple idea: a map

from genotype to fitness, where “the entire field of

possible gene combinations [could] be graded with

respect to adaptive value.”

• Thus, a genotype-to-fitness (G→F) map and

specification of how genotypes are connected

defines an adaptive landscape.

Figure 2 from Wright (1932)

Fitness](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/adaptivelandscapeskerrslides-130828113616-phpapp02/85/Ben-Kerr-Adaptive-landscapes-in-changing-environments-3-320.jpg)