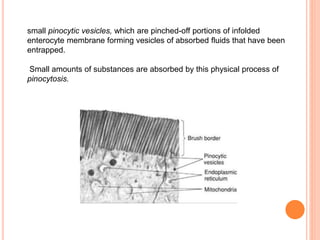

The document summarizes key principles of gastrointestinal absorption. It describes how the stomach, small intestine, and large intestine absorb nutrients and water. The small intestine absorbs the majority of nutrients through structures that increase surface area, like villi and microvilli. Absorption involves active transport processes, like sodium-glucose co-transport, as well as passive diffusion. The large intestine absorbs remaining water before forming feces from undigested material and bacterial byproducts.