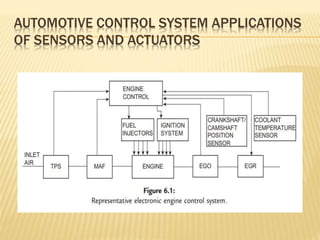

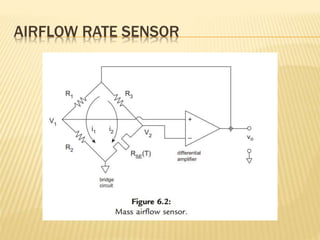

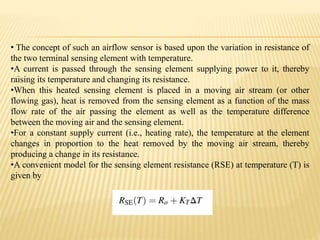

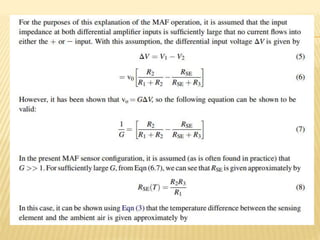

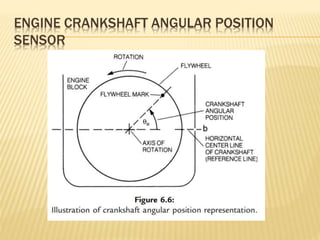

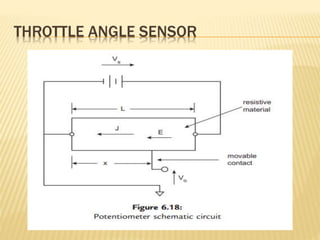

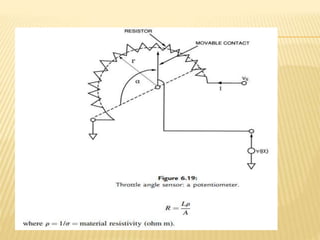

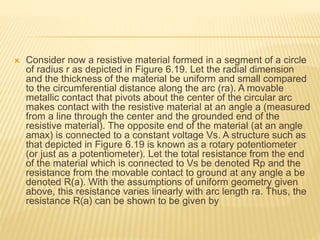

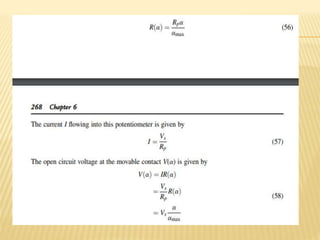

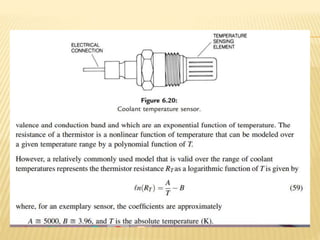

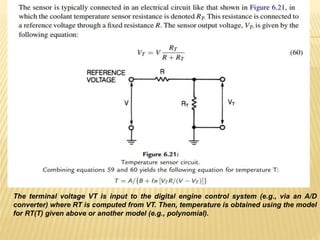

The document summarizes sensors and actuators used in automotive control systems. It describes several common sensors that measure important engine variables like mass air flow, crankshaft position, throttle position, and temperature. It provides details on how sensors like the airflow sensor, crankshaft position sensor, throttle angle sensor, and coolant temperature sensor operate. The document also discusses actuators used to control engine inputs and mentions fuel injectors as an example.