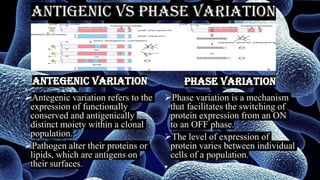

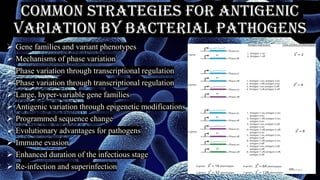

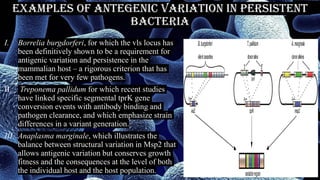

The document discusses antigenic variation in bacteria. It defines antigenic variation as when an infectious agent like a bacterium alters surface proteins or carbohydrates to avoid the host immune response and allow reinfection. This can occur through mechanisms like gene conversion, DNA inversions, or recombination. It allows for a heterogeneous phenotype even in a clonal population. Antigenic variation is important for bacterial pathogens to evade immunity and persist in the host. Examples discussed include Salmonella, Borrelia burgdorferi, and Treponema pallidum.