- The document summarizes an experiment on absorption processes using a countercurrent gas-liquid absorption tower.

- Key findings include developing relationships between liquid flow rate, vapor flow rate, and pressure drop. Generalized correlations were constructed from these relationships.

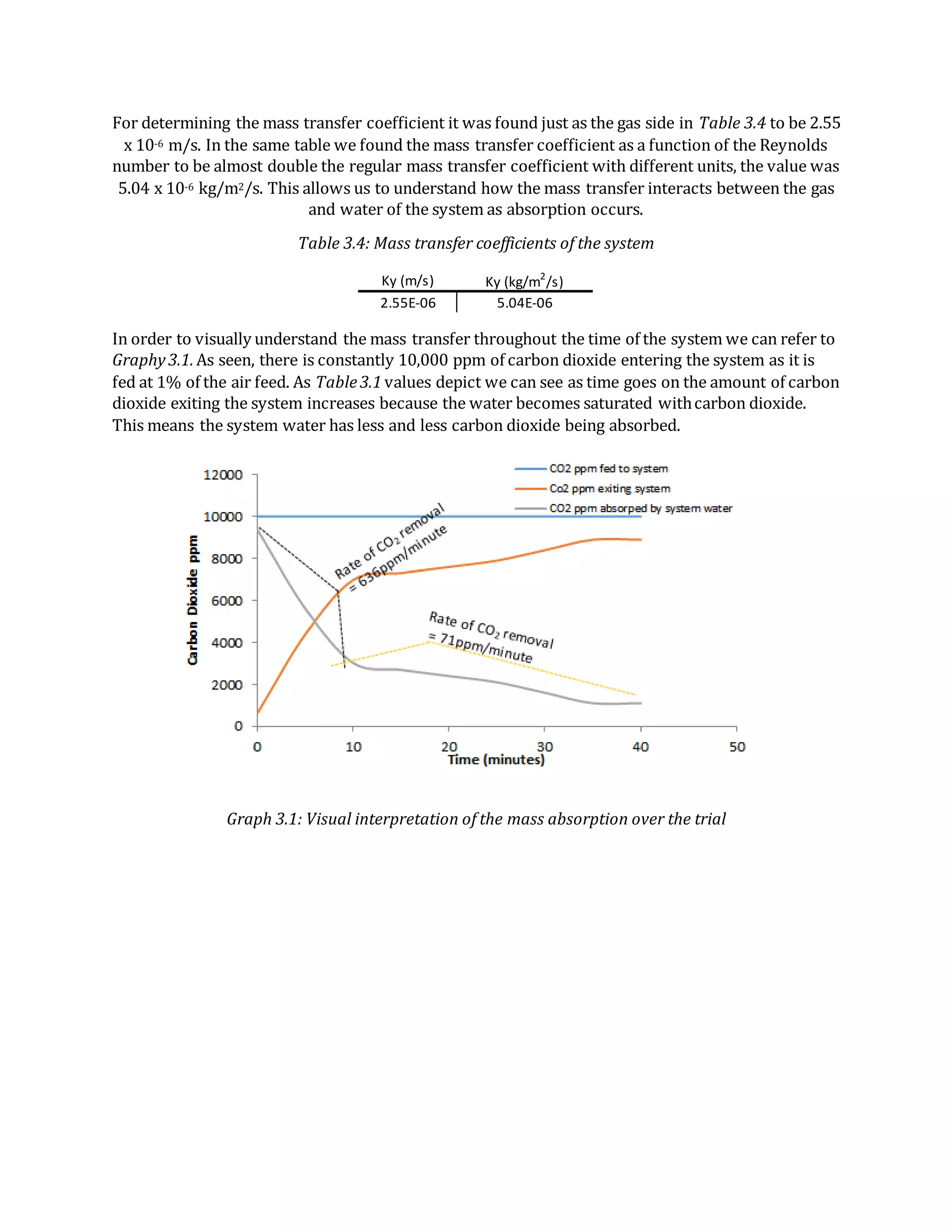

- Absorption of CO2 from air into water was also studied. Data showed decreasing CO2 removal over time as the water became saturated.

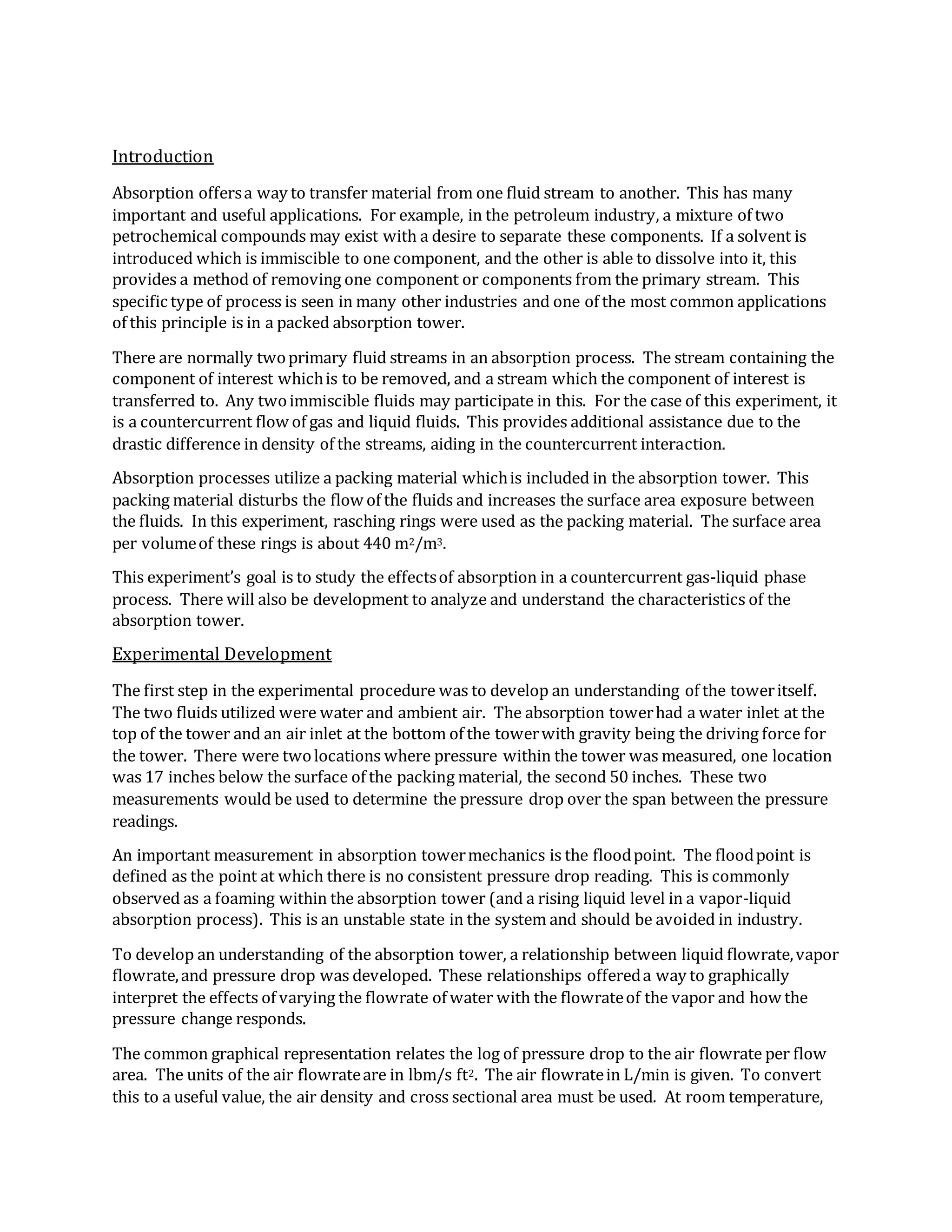

![air density is approximately 1.184 kg/m3 or 0.001184 kg/L. The diameter of the circulartube is 80

mm or 0.2625 ft. This results in a cross sectional area of 0.0541 ft2.The equation used:

𝐺𝑦 = (

𝐴𝑖𝑟 𝐹𝑙𝑜𝑤𝑟𝑎𝑡𝑒 𝐿

𝑠

) (

0.001184 𝑘𝑔

𝐿

) (

2.205 𝑙𝑏

𝑘𝑔

) (

1

0.0514 𝑓𝑡2

) = 𝑀𝑎𝑠𝑠 𝐹𝑙𝑜𝑤𝑟𝑎𝑡𝑒 [

𝑙𝑏

𝑠 𝑓𝑡2

]

This is the same method to calculate the mass flow rate of water which has a density of 1 kg/L.

𝐺𝑥 = (

𝑊𝑎𝑡𝑒𝑟 𝐹𝑙𝑜𝑤𝑟𝑎𝑡𝑒 𝐿

𝑠

) (

1 𝑘𝑔

𝐿

) (

2.205 𝑙𝑏

𝑘𝑔

)(

1

0.0514 𝑓𝑡2

) = 𝑀𝑎𝑠𝑠 𝐹𝑙𝑜𝑤𝑟𝑎𝑡𝑒 [

𝑙𝑏

𝑠 𝑓𝑡2

]

Forming the first relationship, ln(Gy) willrepresent the x-axis of the graphical relationship. The y-

axis is the pressure drop on a logarithmic scale. This is calculated by:

𝑙𝑛 (

𝑃ℎ𝑖𝑔ℎ − 𝑃𝑙𝑜𝑤

∆𝐻

)

This is the difference in pressures divided by the distance between the reading points in the tower.

Creating a generalized correlation would require many data points relating the flow topressure

drop. From the worksheet, there were twoequations identified to represent the x and y axes for

constructing the generalized correlations. They are as follows.

𝑥 − 𝑎𝑥𝑖𝑠:

𝐺𝑥

𝐺𝑦

√

𝜌𝑦

𝜌𝑥

𝑦 − 𝑎𝑥𝑖𝑠:

𝐺𝑦

2 𝐹𝑝 (

62.3

𝜌𝑥

) 𝜇 𝑥

0.2

𝑔 𝑐 𝜌𝑥 𝜌𝑦

Where

𝐹𝑝 − 𝐹𝑙𝑜𝑜𝑑 𝑃𝑜𝑖𝑛𝑡 (= 1024 𝑓𝑡−1)

𝑔 𝑐 − 𝑝𝑟𝑜𝑝𝑜𝑟𝑡𝑖𝑜𝑛𝑎𝑙𝑖𝑡𝑦 𝑓𝑎𝑐𝑡𝑜𝑟 (= 32.174

𝑓𝑡 𝑙𝑏

𝑙𝑏𝑓 𝑠2

)

𝜇 𝑥 − 𝐿𝑖𝑞𝑢𝑖𝑥 𝑣𝑖𝑠𝑐𝑜𝑠𝑖𝑡𝑦 (8.90𝐸 − 4

𝑘𝑔

𝑠 𝑚

)

The relationship between these twoparameters wouldform the generalized correlation.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/absorption-190314072956/75/On-Absorption-Practice-Methods-and-Theory-An-Empirical-Example-3-2048.jpg)

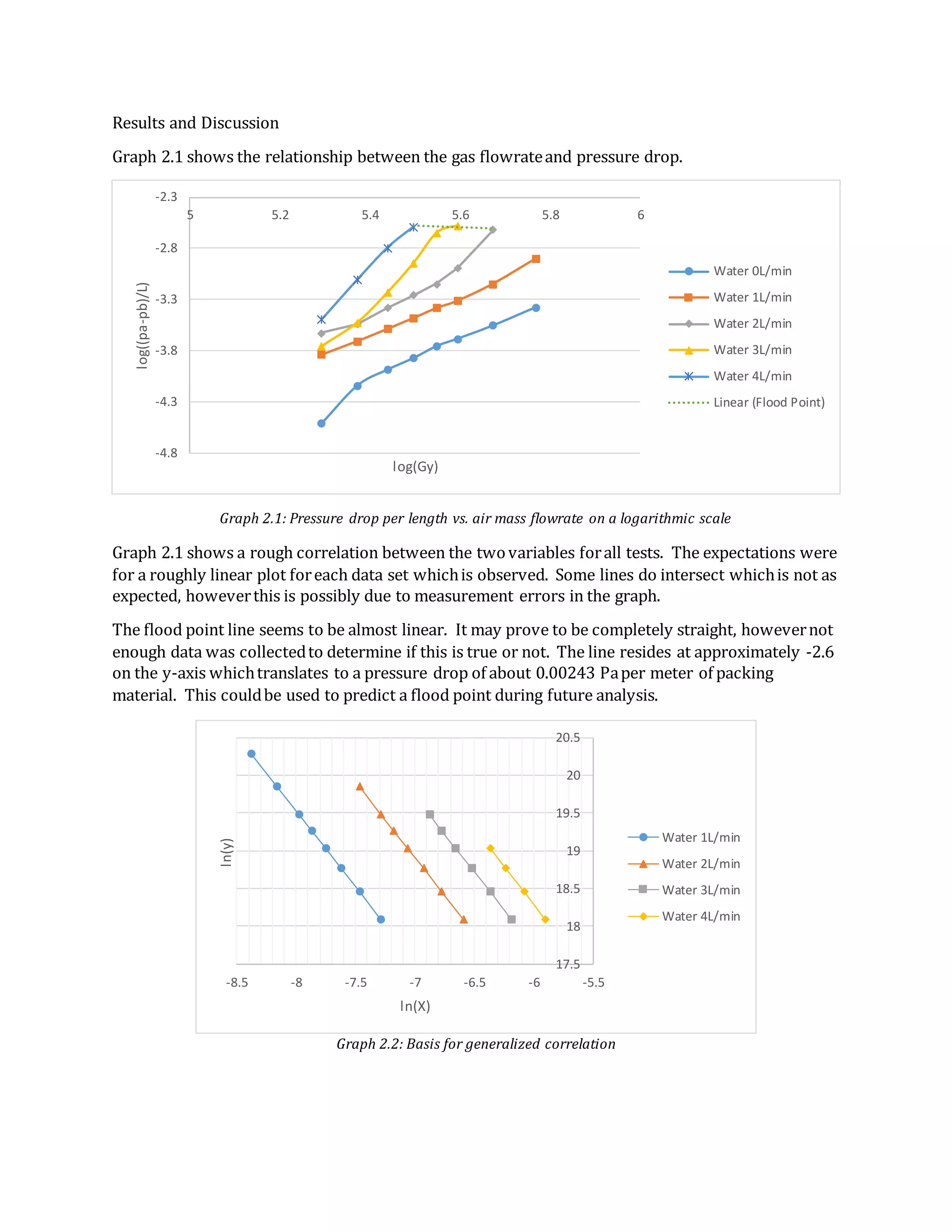

![To constructthe generalized correlation, a graph of the data points was generated at first. This is

shown as Graph 2.2 with each data set corresponding to a different water flowrate. The axes are

described in the experimental development section and willbe restated.

𝑥 − 𝑎𝑥𝑖𝑠:

𝐺𝑥

𝐺𝑦

√

𝜌𝑦

𝜌𝑥

𝑦 − 𝑎𝑥𝑖𝑠:

𝐺𝑦

2 𝐹𝑝 (

62.3

𝜌𝑥

) 𝜇 𝑥

0.2

𝑔 𝑐 𝜌𝑥 𝜌𝑦

Eachpoint represents a different pressure drop relation. Again, the pressure drop is calculated

with respect to the total height difference. The units are also important as well.

𝑃𝑟𝑒𝑠𝑠𝑢𝑟𝑒 𝐷𝑟𝑜𝑝 =

𝑃ℎ𝑖𝑔ℎ − 𝑃𝑙𝑜𝑤

ℎ𝑒𝑖𝑔ℎ𝑡

[

𝑖𝑛 𝐻2 𝑂

𝑓𝑡

]

To constructthe correlation, points with similar pressure drops werefocused on and assessed for

the accuracy of the regression. This is shown in Graph 2.3.

Graph 2.3: Linear regression of pressure drops. See Table 2.1 for the parameters of each line moving from the

top line downward.

These regressions were significantly accurate and provided a basis forthe graphical construction.

The R2 values were all above 0.95 confirming the accuracy of the measurements. The linear

regression was accurateenough to remain the desired correlation method (as opposed to

exponential or other). The results are shown in Table 2.1 withthe slope of each line, the intercept,

the pressure drop value corresponding to the line, and the R2 value. The table is ordered so that

each column position relates to the position of each line in the graph, highest being first, lowest

being last. For example, the “floodpoint” line is the uppermost line on the graph. “Line 5” is the

lowermost line on the graph.

17.5

18

18.5

19

19.5

20

20.5

-9 -8.5 -8 -7.5 -7 -6.5 -6 -5.5

ln(y)

ln(x)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/absorption-190314072956/75/On-Absorption-Practice-Methods-and-Theory-An-Empirical-Example-5-2048.jpg)

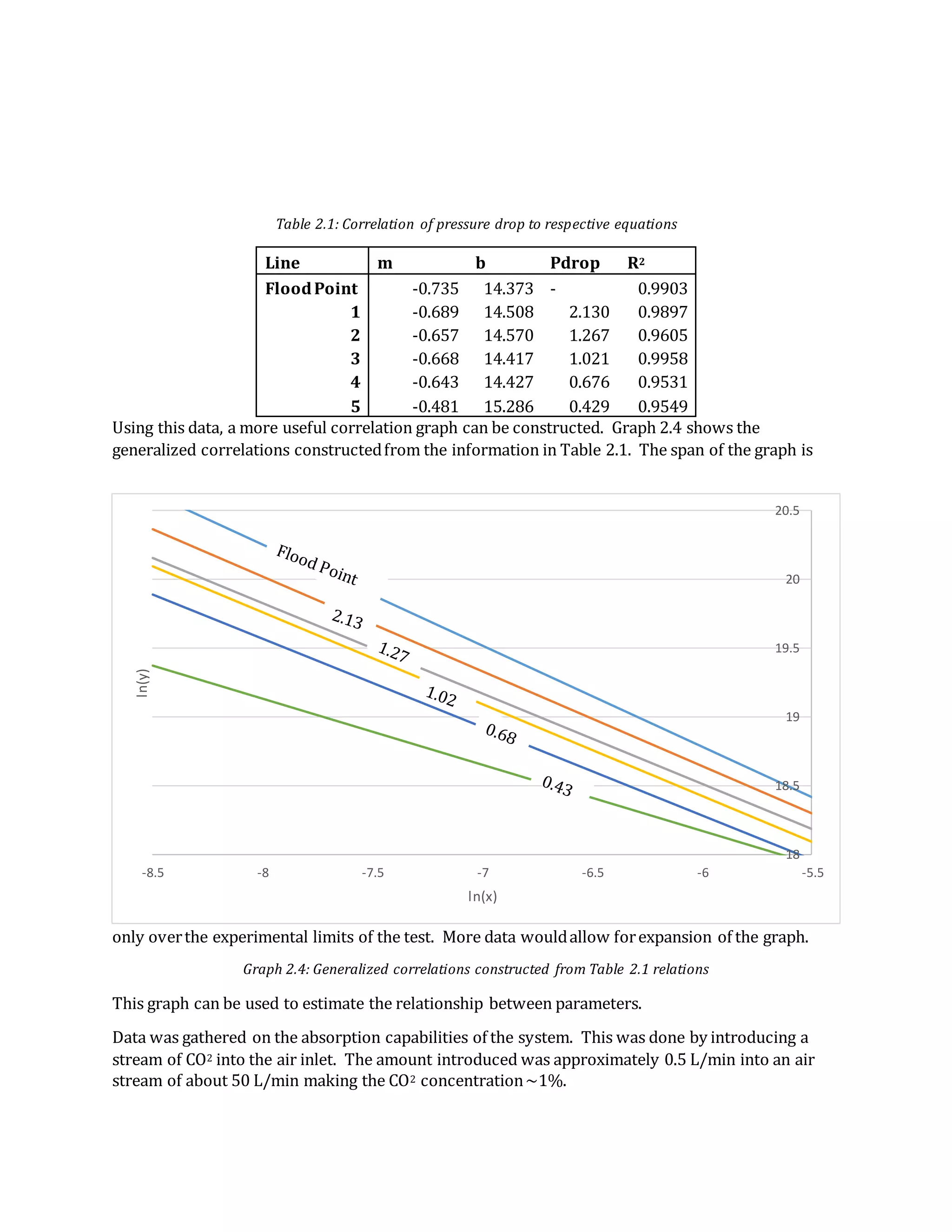

![Table 3.1: ppm Balance of the absorption tower

In Table3.2 a very similar balance is done but instead of ppm the numbers have been converted

into moles of carbon dioxide in water.Similar explanations and ideas revolvearound this table as

they do for the discussion of Table3.1. Using this table we can determine that roughly 0.035 moles

of carbon dioxide are now in the water.

Table 3.2: mole balance of the Absorption Tower

Here in Table3.3 we can observe how the rate of carbon dioxide removal from the gas phase by

absorption in water changes throughout the experiment. For the first ten minutes the rate of

removal was very high and efficientat around 640 ppm/min of carbonremoved fromgas phase.

After ten minutes the water became toosaturated and the rate of removal dropped to 71 ppm/min.

The last removal rate that we lookedat is the bold number whichdetermines the rate over the

entire forty minute period, we found that the overall rate of carbon dioxide removal from the gas

phase by absorption by water was 207 ppm/min.

Table 3.3: Rate of Removal of Carbon Dioxide

Time (min) pH (z)

CO2 ppm fed to

system

Co2 ppm exiting

system

CO2 ppm

absorped by

system water

0 10.5 10000 617 9383

5 10.5 10000 4381 5619

10 10.1 10000 6980 3020

15 10.1 10000 7310 2690

20 9.9 10000 7600 2400

25 9.8 10000 7900 2100

30 9.7 10000 8400 1600

35 9.7 10000 8900 1100

40 9.5 10000 8900 1100

Time (min) pH (z) Exit CO2 mol frac Exit CO2 moles/min [H+] ions Ct (moles/L)

Moles

CO2 in

water

CO2

Moles

leaving

0 10.5 0.0006 0.0013 3.16E-11 -1.14E-06 0.0000 0.0000

5 10.5 0.0044 0.0090 3.16E-11 -1.14E-06 0.0000 0.0448

10 10.1 0.0070 0.0143 7.94E-11 1.10E-04 0.0031 0.1429

15 10.1 0.0073 0.0150 7.94E-11 1.10E-04 0.0031 0.2244

20 9.9 0.0076 0.0156 1.26E-10 1.62E-04 0.0046 0.3111

25 9.8 0.0079 0.0162 1.58E-10 1.85E-04 0.0053 0.4043

30 9.7 0.0084 0.0172 2.00E-10 2.05E-04 0.0059 0.5158

35 9.7 0.0089 0.0182 2.00E-10 2.05E-04 0.0059 0.6376

40 9.5 0.0089 0.0182 3.16E-10 2.39E-04 0.0068 0.7287

Time

Range

(min)

Rate of

Removal

(ppm/min)

0 - 10 636

10 - 40 71

0 - 40 207](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/absorption-190314072956/75/On-Absorption-Practice-Methods-and-Theory-An-Empirical-Example-8-2048.jpg)

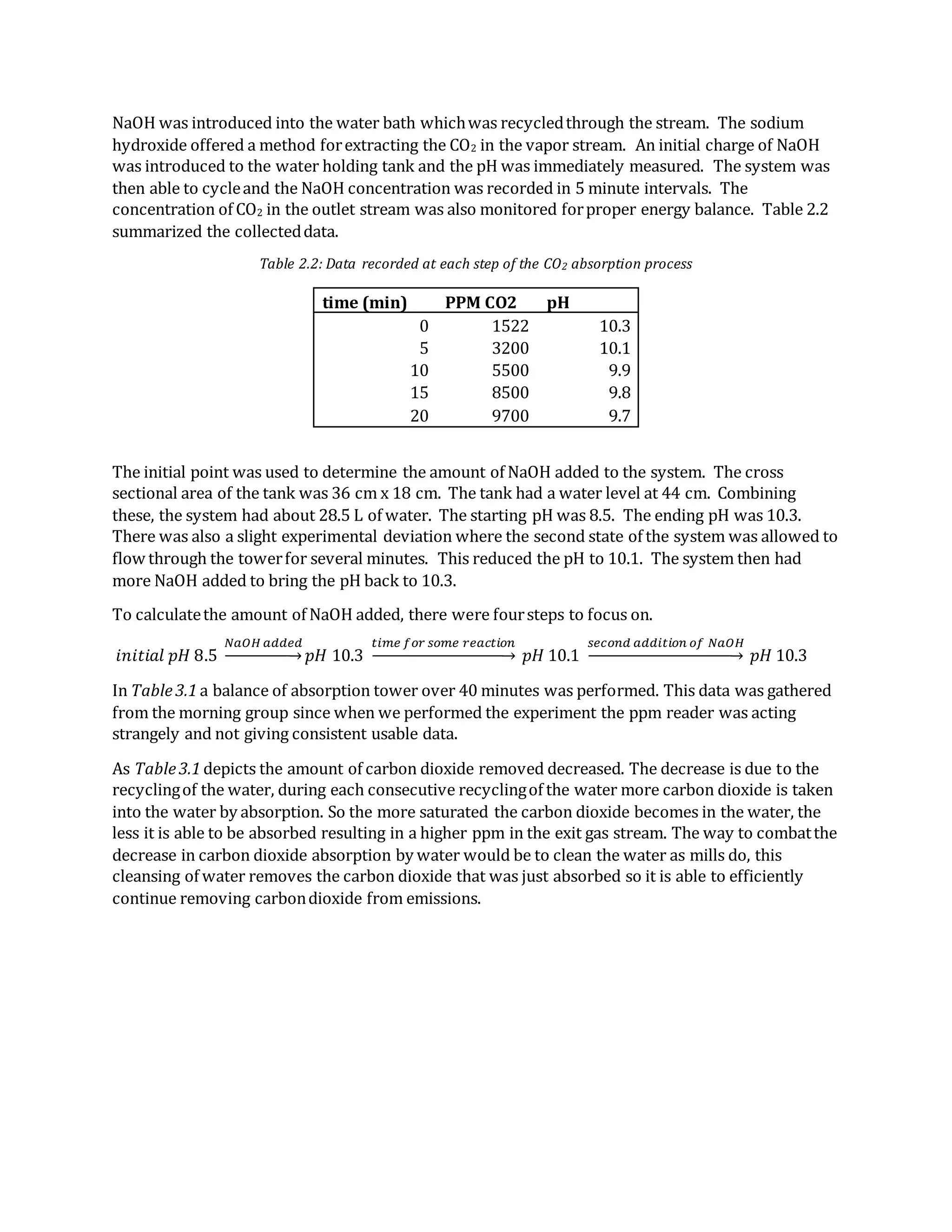

![Table 4: Tabulation of back calculated values for the addition on NaOH to raise pH from 8.3

to 10.3

Additional Notes and Further Inquiry:

The back calculationof the mass of NaOH needed to be added to our system to raise the pH

by three points was rather straightforward. It also yielded results that were pretty close to the

actual, known value of NaOH added to the system. The principal behind this calculation was that pH

is based off of molarity, whichis a concentration measurement. The pH gave us a moles/liter value.

As shown above,we calculated these values. From there, we knew that there was about 28.5 liters

of water solution in out system. This allowed us to multiply the difference in molarities by the

amount of liters of solution. The stoichiometry of NaOH and H2O is one to one, so a direct molar

correlation could be achieved. This yielded a molar value forNaOH. From there, the molecular

weight was used to yield a final mass value, of about 4.4 grams of NaOH. As noted before, we knew

the amount of NaOH that we added, because we weighed it before the addition. Our measured

weight was about 4.1 grams. This value is very closeto the theoretically calculated value. Some

reasons why it coulddiffer slightly are that while the waterwas flowing,residual acidic media may

have been left overon the walls and parts of the system. Also, human error in calculation probably

played a role in the discrepancy. Overall,we were not very surprised by this calculation and

expected a small error involved.

Please Inquire at lehmanjw@miamioh.edu

Back Calculated Parameters Calculated Value

Molarity of Solution at pH of 8.3 [H+] 5.013 x 10-9 moles/liter

Molarity of Solution at pH of 10.3 [H+] 5.001 x 10-11 moles/liter

Moles of NaOH needed to be added 0.110 moles NaOH

Weight of NaOH to be added (39.9 g/mol) 4.412 grams NaOH](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/absorption-190314072956/75/On-Absorption-Practice-Methods-and-Theory-An-Empirical-Example-10-2048.jpg)