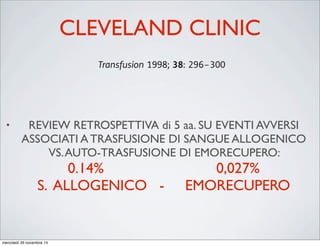

This study analyzed 45 observational studies including over 272,000 patients to determine the association between red blood cell transfusion and morbidity and mortality in high-risk hospitalized patients. The analysis found that in 42 of the 45 studies, the risks of red blood cell transfusion outweighed the benefits, with transfusion associated with increased risk of death, infections, multi-organ dysfunction syndrome, and acute respiratory distress syndrome. A meta-analysis found that transfusion was associated with 70% higher odds of death and 80% higher odds of developing an infectious complication. The study suggests current transfusion practices may need reevaluation given the risks appear to outweigh the benefits in most patients.

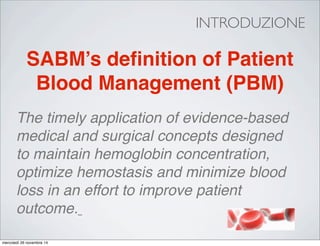

![Review Article

Efficacy of red blood cell transfusion in the critically ill:

A systematic review of the literature*

Paul E. Marik, MD, FACP, FCCM, FCCP; Howard L. Corwin, MD, FACP, FCCM, FCCP

In recent years red blood cell

(RBC) transfusion requirements

in western nations has been in-

creasing because of the increasing

burden of chronic disease in an aging

population, improvement in life-support

technology, and blood-intensive surgical

procedures (1, 2). In the United States

alone, nearly 15 million units of blood are

donated and 13 million units are trans-

fused annually (2). For much of the last

(3). On the other hand, it is now becom-

ing clear that there are other important,

less recognized risks of RBC transfusion

related to RBC storage effects and to im-

munomodulating effects of RBC transfu-

sions, which occur in almost all recipi-

ents (4). These immunomodulating*See also p. 2707.

From the Division of Pulmonary and Critical Care

Background: Red blood cell (RBC) transfusions are common in

intensive care unit, trauma, and surgical patients. However, the

hematocrit that should be maintained in any particular patient

because the risks of further transfusion of RBC outweigh the

benefits remains unclear.

Objective: A systematic review of the literature to determine

the association between red blood cell transfusion, and morbidity

and mortality in high-risk hospitalized patients.

Data Sources: MEDLINE, Embase, Cochrane Register of Con-

trolled Trials, and citation review of relevant primary and review

articles.

Study Selection: Cohort studies that assessed the independent

effect of RBC transfusion on patient outcomes. From 571 articles

screened, 45 met inclusion criteria and were included for data

extraction.

Data Extraction: Forty-five studies including 272,596 were

identified (the outcomes from one study were reported in four

separate publications). The outcome measures were mortality,

infections, multiorgan dysfunction syndrome, and acute respira-

tory distress syndrome. The overall risks vs. benefits of RBC

transfusion on patient outcome in each study was classified as (i)

risks outweigh benefits, (ii) neutral risk, and (iii) benefits out-

weigh risks. The odds ratio and 95% confidence interval for each

outcome measure was recorded if available. The pooled odds

ratios were determined using meta-analytic techniques.

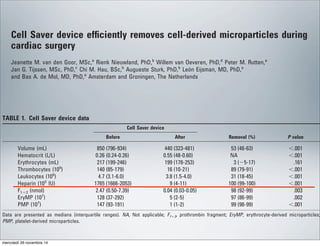

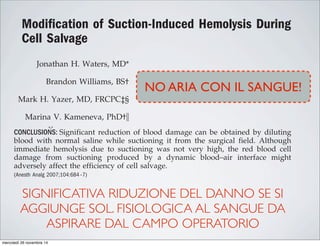

Data Synthesis: Forty-five observational studies with a median

of 687 patients/study (range, 63–78,974) were analyzed. In 42 of

the 45 studies the risks of RBC transfusion outweighed the

benefits; the risk was neutral in two studies with the benefits

outweighing the risks in a subgroup of a single study (elderly

patients with an acute myocardial infarction and a hematocrit

<30%). Seventeen of 18 studies, demonstrated that RBC trans-

fusions were an independent predictor of death; the pooled odds

ratio (12 studies) was 1.7 (95% confidence interval, 1.4؊1.9).

Twenty-two studies examined the association between RBC

transfusion and nosocomial infection; in all these studies blood

transfusion was an independent risk factor for infection. The

pooled odds ratio (nine studies) for developing an infectious

complication was 1.8 (95% confidence interval, 1.5–2.2). RBC

transfusions similarly increased the risk of developing multi-

organ dysfunction syndrome (three studies) and acute respiratory

distress syndrome (six studies). The pooled odds ratio for devel-

oping acute respiratory distress syndrome was 2.5 (95% confi-

dence interval, 1.6–3.3).

Conclusions: Despite the inherent limitations in the analysis of

cohort studies, our analysis suggests that in adult, intensive care

unit, trauma, and surgical patients, RBC transfusions are associated

with increased morbidity and mortality and therefore, current trans-

fusion practices may require reevaluation. The risks and benefits of

RBC transfusion should be assessed in every patient before transfu-

sion. (Crit Care Med 2008; 36:2667–2674)

KEY WORDS: blood; blood transfusion; anemia; infections; im-

munomodulation; transfusion-related acute lung injury; acute re-

spiratory distress syndrome; mortality; systematic analysis; meta-

analysis

Morbidity and mortality risk associated with red blood cell

and blood-component transfusion in isolated coronary artery

bypass grafting*

Colleen Gorman Koch, MD, MS; Liang Li, PhD; Andra I. Duncan, MD; Tomislav Mihaljevic, MD;

Delos M. Cosgrove, MD; Floyd D. Loop, MD; Norman J. Starr, MD; Eugene H. Blackstone, MD

A

dministration of packed red

blood cells (PRBCs) has been

associated with morbidity and

mortality for both medical and

surgical patients (1–13). Transfusions are

(2, 8) and long-term mortality (12). Gong

et al. (14) recently demonstrated the as-

sociation between PRBC transfusion and

the development and increased mortality

from acute respiratory distress syndrome.

Our objectives were 1) to exam

whether each unit of PRBC transfu

perioperatively conferred increment

increased risk for mortality and m

morbid outcomes in a large homo

Objective: Our objective was to quantify incremental risk asso-

ciated with transfusion of packed red blood cells and other blood

components on morbidity after coronary artery bypass grafting.

Design: The study design was an observational cohort study.

Setting: This investigation took place at a large tertiary care

referral center.

Patients: A total of 11,963 patients who underwent isolated

coronary artery bypass from January 1, 1995, through July 1,

2002.

Interventions: None.

Measurements and Main Results: Among the 11,963 patients

who underwent isolated coronary artery bypass grafting, 5,814

(48.6%) were transfused. Risk-adjusted probability of developing

in-hospital mortality and morbidity as a function of red blood cell

and blood-component transfusion was modeled using logistic

regression. Transfusion of red blood cells was associated with a

risk-adjusted increased risk for every postoperative morbid ev

mortality (odds ratio [OR], 1.77; 95% confidence interval

1.67–1.87; p < .0001), renal failure (OR, 2.06; 95% CI, 1.87–2

p < .0001), prolonged ventilatory support (OR, 1.79; 95%

1.72–1.86; p < .0001), serious infection (OR, 1.76; 95% CI, 1.68–1

p < .0001), cardiac complications (OR, 1.55; 95% CI, 1.47–1

p < .0001), and neurologic events (OR, 1.37; 95% CI, 1.30–1.44;

.0001).

Conclusions: Perioperative red blood cell transfusion is

single factor most reliably associated with increased risk

postoperative morbid events after isolated coronary artery byp

grafting. Each unit of red cells transfused is associated w

incrementally increased risk for adverse outcome. (Crit Care

2006; 34:1608–1616)

KEY WORDS: blood cells; hemoglobin; complications; cardio

monary bypass; cardiovascular disease; mortality

Transfusion of fresh frozen plasma in critically ill surgical patients

is associated with an increased risk of infection

Babak Sarani, MD, FACS; W. Jonathan Dunkman, BA; Laura Dean; Seema Sonnad, PhD;

Jeffrey I. Rohrbach, RN, MSN; Vicente H. Gracias, MD, FACS

Objective: To determine whether there is an association be-

tween transfusion of fresh frozen plasma and infection in criti-

cally ill surgical patients.

Design: Retrospective study.

Setting: A 24-bed surgical intensive care unit in a university

hospital.

Patients: A total of 380 non-trauma patients who received

fresh frozen plasma from 2004 to 2005 were compared with 2,058

nontrauma patients who did not receive fresh frozen plasma.

Interventions: None.

Measurements and Main Results: We calculated the relative

risk of infectious complication for patients receiving and not

receiving fresh frozen plasma. T-test allowed comparison of av-

erage units of fresh frozen plasma transfused to patients with and

associated pneumonia without shock (relative risk 1.97, 1.03–

3.78), bloodstream infection with shock (relative risk 3.35, 1.69–

6.64), and undifferentiated septic shock (relative risk 3.22, 1.84–

5.61). The relative risk for transfusion of fresh frozen plasma and

all infections was 2.99 (2.28–3.93). The t-test revealed a signifi-

cant dose-response relationship between fresh frozen plasma and

infectious complications (p ؍ .02). Chi-square analysis showed a

significant association between infection and transfusion of fresh

frozen plasma in patients who did not receive concomitant red

blood cell transfusion (p < .01), but this association was not

significant in those who did receive red blood cells in addition to

fresh frozen plasma. The association between fresh frozen

plasma and infectious complications remained significant in the

multivariate model, with an odds ratio of infection per unit of

Allogeneic Blood Transfusion Increases the Risk of

Postoperative Bacterial Infection: A Meta-analysis

Gary E. Hill, MD, William H. Frawley, PhD, Karl E. Griffith, MD, John E. Forestner, MD, and

Joseph P. Minei, MD

Background: Immunosuppression is

a consequence of allogeneic (homologous)

tions that included only the traumatically

injured patient was included in a separate

subgroup of trauma patien

(range, 5.03–5.43), with all stud

The Journal of TRAUMA Injury, Infection, and C

mercoledì 26 novembre 14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romaint-160320122837/85/A-fresh-look-at-cell-salvage-3-320.jpg)

![FORMAZIONE

USA

• PBMT : Perioperative Blood Management

Technologist

ESAME

K = conoscenza

S = abilità

A = pratica

Perioperative Blood Management Technologist [PBMT]

Job Domain Analysis

Theoretical Hierarchical Construct for K/S/A for Competency Exam

Respond correctly to

critical incidents and

emergencies [4.3]

Follow guideline

indications for use and

record keeping [3.3]

Disposable supplies

and interface with

hardware [2.3]

Inter-team member

communication and

patient privacy [1.3}

Communication with

team during critical

incident and crisis

management [4.4]

Follow guidelines

recognizing

contraindications and

exceptions [3.4]

Follow manufacturer

instructions-for-use

and assembly [2.4]

Integration into surgical

team and participate in

care planning and quality

management [1.4]

Design and practice

team drills for critical

incidents [4.5]

Suggest changes to and

author clinical procedure

guidelines [3.5]

Application and

operation of

equipment [2.5]

Assertiveness, lead team

when required [1.5]

Critical

Incidents

Patient Care

Procedures

Equipment /

Disposables

Environmental

Factors

K/S/A Label Count Percent

K Knowledge 45 0.41

S Skills 31 0.28

A Application 34 0.31

Total 110 1.00

mercoledì 26 novembre 14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romaint-160320122837/85/A-fresh-look-at-cell-salvage-19-320.jpg)

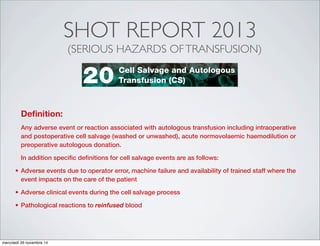

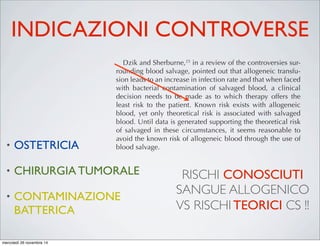

![reinfusion of salvaged blood was continued without the LDF and no hypotension occurred. This is a

recognised complication which may be related to elevated levels of interleukin 6 [71], and is reviewed

by Sreelakshmi [72].

Learning points

The use of leucodepletion filters (LDF) with cell salvaged blood can, rarely, cause significant

hypotension

Stopping the infusion and resuscitation with fluids and vasopressors may be necessary although

all reports describe only transient hypotension

In cases where there is brisk haemorrhage and the blood is needed, try infusing without the LDF

Recommendations

Ensure that all cell salvage users in your institution are made aware of this complication and the

simple measures that need to be taken should it occur

Action: Hospital Transfusion Committees (HTC), Hospital Transfusion Teams (HTT)

Ensure all cases of serious reactions are reported to SHOT via the hospital transfusion team

Action: HTTs, Operating Department Practitioners, Cell Salvage Operators

Consider where a machine failure occurs, which is not due to operator error, these are reported

to the Medicines and Healthcare products Regulatory Agency (MHRA) under the Medical Devices

reporting schememercoledì 26 novembre 14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romaint-160320122837/85/A-fresh-look-at-cell-salvage-37-320.jpg)

![plasma, and cryoprecipitate. Anticipate coagulation factor

deficiency after more than 2 litres blood loss with continued bleed-

ing and repeat full blood count, prothrombin time, and activated

partial thromboplastin time and fibrinogen levels after the reinfu-

sion of each litre of salvaged blood in order to detect and appropri-

ately treat coagulapathy (Table 1).

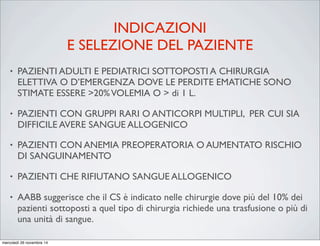

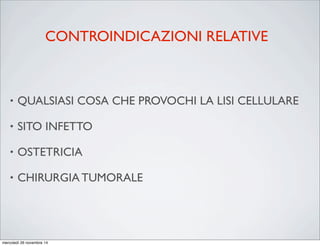

General indications for cell salvage

(i) Anticipated intraoperative blood loss .1 litre or .20% of

blood volume.

(ii) Preoperative anaemia or increased risk factors for bleeding.

(iii) Patients with rare blood group or antibodies.

(iv) Patient refusal to receive allogeneic blood transfusion.

(v) The American Association of Blood Banks suggest cell

salvage is indicated in surgery where blood would ordinarily

be cross-matched or where more than 10% of patients under-

going the procedure require transfusion.

allo

fixe

requ

pro

was

cran

plas

Sp

Cel

enc

ord

in p

pro

afte

Hom

safe

Perioperative cell salvage

Lakshminarasimhan Kuppurao MD DA DNB FRCA

Michael Wee BSc (Hons) MBChB FRCA

The National Blood Service for England col-

lects, tests, processes, stores, and issues 2.1

million blood donations each year, and the

optimal use of this scarce resource is of para-

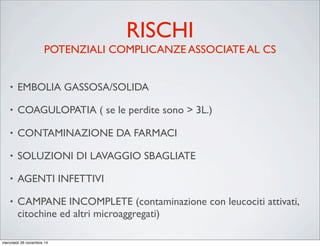

mount importance. Allogeneic red blood cell

(RBC) transfusion is associated with well-

known adverse effects. These include febrile,

anaphylactic, and haemolytic transfusion reac-

Key points

Complications of allogeneic

transfusion are rare but can

be life threatening.

There is a drive to reduce

allogeneic blood transfusion

due to cost and scarcity.

Cell salvage should be used

e cell salvage

purao MD DA DNB FRCA

s) MBChB FRCA

The National Blood Service for England col-

lects, tests, processes, stores, and issues 2.1

million blood donations each year, and the

optimal use of this scarce resource is of para-

mount importance. Allogeneic red blood cell

(RBC) transfusion is associated with well-

known adverse effects. These include febrile,

anaphylactic, and haemolytic transfusion reac-

tions, transfusion-related acute lung injury, and

transfusion-associated circulatory overload. In

addition, although rare, there are infection risks

of viral, bacterial, parasitic, or prion trans-

mission. In the laboratory setting, allogeneic

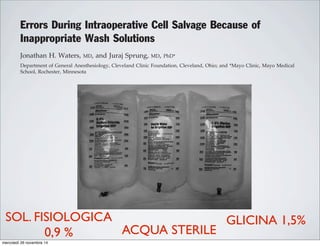

involves filtering and washing to remove con-

taminants. Red cells are retained, while the

plasma, platelets, heparin, free haemoglobin,

and inflammatory mediators are discarded with

the wash solution. This process may be discon-

tinuous or continuous, and the resulting red

cells are finally resuspended in normal saline at

a haematocrit of 50–70%, and reinfused into

the patient. Once primed, the cell salvage

machine should be used within 8 h to prevent

infective complications.

Benefits of cell salvage

Matrix reference 1A06

evolved since its inception in the 1960s.

Initially, cell salvage was limited to simply fil-

tering blood loss during surgery by gravity.

More modern devices collect blood to which is

added heparinized normal saline or citrate

anticoagulant. Processing the collected blood

activation of intravascular coagulation

increased capillary permeability causing

lung injury and renal failure. This syndr

related to the dilution of salvaged blood

large quantities of saline solution,

creates deposits of cellular aggregates

doi:10.1093/bjaceaccp/mkq017 Advance Access publication 26 M

Continuing Education in Anaesthesia, Critical Care & Pain | Volume 10 Number 4 2010

& The Author [2010]. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of the British Journal of Anaesthesia.

All rights reserved. For Permissions, please email: journals.permissions@oxfordjournal.org

mercoledì 26 novembre 14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romaint-160320122837/85/A-fresh-look-at-cell-salvage-41-320.jpg)

![Intraoperative blood salvage in cancer surgery:

safe and effective?

Ernil Hansen *, Volker Bechmann, Juergen Altmeppen

Department of Anesthesiologie, University of Regensburg, D-93042 Regensburg, Germany

Abstract

To support blood supply in the growing field of cancer surgery and to avoid transfusion induced immunomodulation

caused by the allogeneic barrier and by blood storage leasions we use intraoperative blood salvage with blood irra-

diation. This method is safe as it provides efficient elimination of contaminating cancer cells, and as it does not

compromise the quality of RBC. According to our experience with more than 700 procedures the combination of blood

salvage with blood irradiation also is very effective in saving blood resources. With this autologous, fresh, washed RBC

a blood product of excellent quality is available for optimal hemotherapy in cancer patients.

Ó 2002 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved.

1. Introduction

The demand for blood in cancer surgery is high

and increasing. Problems with the supply of com-

patible blood are not uncommon in these patients

that previously have seen surgery and transfusions.

Some transfusion risks are especially relevant to

cancer patients like immunomodulation with im-

donations suffers from the poor predictability of

intraoperative blood loss leading to a waste of

autologous blood, or to insufficient supply. Im-

munosuppression is not only caused by the allog-

eneic barrier, but also by cell lesions during blood

storage at low temperature [2], relevant to both

allogeneic and autologous banked blood. In ad-

dition, growth factors are released during storage

www.elsevier.com/locate/transci

Intraoperative blood salvage in cancer surgery

safe and effective?

Ernil Hansen *, Volker Bechmann, Juergen Altmeppen

Department of Anesthesiologie, University of Regensburg, D-93042 Regensburg, Germany

act

support blood supply in the growing field of cancer surgery and to avoid transfusion induced imm

d by the allogeneic barrier and by blood storage leasions we use intraoperative blood salvage w

www.elsevier.

Transfusion and Apheresis Science 27 (2002) 153–157

Fig. 1. Transfusion risks most relevant to cancer patients.

E. Hansen et al. / Transfusion and Apheresis Science 27 (2002) 153–157

più di 700 casi

irradiazione GRC

50Gy

diminuzione cellule

tumorali Log 12

ottima qualità,

sopravvivenza,

funzione

mercoledì 26 novembre 14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romaint-160320122837/85/A-fresh-look-at-cell-salvage-53-320.jpg)

![2011 Update to The Society of Thoracic Surgeons

and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists

Blood Conservation Clinical Practice Guidelines*

The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Blood Conservation Guideline Task Force:

Victor A. Ferraris, MD, PhD (Chair), Jeremiah R. Brown, PhD, George J. Despotis, MD,

John W. Hammon, MD, T. Brett Reece, MD, Sibu P. Saha, MD, MBA,

Howard K. Song, MD, PhD, and Ellen R. Clough, PhD

The Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists Special Task Force on Blood Transfusion:

Linda J. Shore-Lesserson, MD, Lawrence T. Goodnough, MD, C. David Mazer, MD,

Aryeh Shander, MD, Mark Stafford-Smith, MD, and Jonathan Waters, MD

The International Consortium for Evidence Based Perfusion:

Robert A. Baker, PhD, Dip Perf, CCP (Aus), Timothy A. Dickinson, MS,

Daniel J. FitzGerald, CCP, LP, Donald S. Likosky, PhD, and Kenneth G. Shann, CCP

Division of Cardiovascular and Thoracic Surgery, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky (VAF, SPS), Department of

Anesthesiology, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (JW), Departments of Anesthesiology and Critical

Care Medicine, Englewood Hospital and Medical Center, Englewood, New Jersey (AS), Departments of Pathology and Medicine,

Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, California (LTG), Departments of Anesthesiology and Cardiothoracic Surgery,

Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, New York (LJS-L, KGS), Departments of Anesthesiology, Immunology, and Pathology, Washington

University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri (GJD), Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, Section of

Cardiology, Dartmouth Medical School, Lebanon, New Hampshire (JRB), Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Wake Forest School of

Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina (JWH), Department of Anesthesia, St. Michael’s Hospital, University of Toronto, Toronto,

Ontario (CDM), Cardiac Surgical Research Group, Flinders Medical Centre, South Australia, Australia (RAB), Department of Surgery,

Medicine, Community and Family Medicine, and the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, Dartmouth Medical

School, Hanover, New Hampshire (DSL), SpecialtyCare, Nashville, Tennessee (TAD), Department of Cardiac Surgery, Brigham and

Women’s Hospital, Harvard University, Boston, Massachusetts (DJF), Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Oregon Health and Science

University Medical Center, Portland, Oregon (HKS), Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, University of Colorado Health Sciences

Center, Aurora, Colorado (TBR), Department of Anesthesiology, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina (MS-S), and

The Society of Thoracic Surgeons, Chicago, Illinois (ERC)

Background. Practice guidelines reflect published liter- Methods. The search methods used in the current

pro-

bolic

ports

with

213].

t re-

lica-

that

om-

g, or

per-

ICU

Two

ship

pa-

volv-

diac

tar-

mbo-

able [227], and addition of factor concentrates augments

multiple other interventions. Fractionated factor concen-

trates, like factor IX concentrates or one of its various

forms (Beriplex or factor VIII inhibitor bypassing activ-

ity), are considered “secondary components” and may be

acceptable to some Jehovah’s Witness patients [222].

Addition of factor IX concentrates may be most useful in

the highest risk Jehovah’s Witness patients.

d) Blood Salvage Interventions

EXPANDED USE OF RED CELL SALVAGE USING CENTRIFUGATION

Class IIb.

1. In high-risk patients with known malignancy who

require CPB, blood salvage using centrifugation of

blood salvaged from the operative field may be

considered since substantial data support benefit in

patients without malignancy, and new evidence

suggests worsened outcome when allogeneic trans-

fusion is required in patients with malignancy.

(Level of evidence B)

In 1986, the American Medical Association Council on

Scientific Affairs issued a statement regarding the safety

of blood salvage during cancer surgery [228]. At that

time, they advised against its use. Since then, 10 obser-

vational studies that included 476 patients who received

blood salvage during resection of multiple different tumor

types involving the liver [229–231], prostate [232–234],

uterus [235, 236], and urologic system [237, 238] support the

use of salvage of red cells using centrifugation in cancer

patients. In seven studies, a control group received no

transfusion, allogeneic transfusion, or preoperative autolo-

end of CPB is reasonable as part of a bl

agement program to minimize blood tr

(Level of evidence C)

2. Centrifugation instead of direct infusion o

pump blood is reasonable for minimizing

allogeneic RBC transfusion. (Level of evi

Most surgical teams reinfuse blood from t

poreal circuit (ECC) back into patients at the

as part of a blood conservation strategy. Cu

blood salvaging techniques exist: (1) direct

post-CPB circuit blood with no processing;

cessing of the circuit blood, either by centrifu

ultrafiltration, to remove either plasma com

water soluble components from blood before

Ann Thorac Surg FERRARIS

2011;91:944–82 STS BLOOD CONSERVATION REVISION

mercoledì 26 novembre 14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romaint-160320122837/85/A-fresh-look-at-cell-salvage-54-320.jpg)

![2011 Update to The Society of Thoracic Surgeons

and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists

Blood Conservation Clinical Practice Guidelines*

The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Blood Conservation Guideline Task Force:

Victor A. Ferraris, MD, PhD (Chair), Jeremiah R. Brown, PhD, George J. Despotis, MD,

John W. Hammon, MD, T. Brett Reece, MD, Sibu P. Saha, MD, MBA,

Howard K. Song, MD, PhD, and Ellen R. Clough, PhD

The Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists Special Task Force on Blood Transfusion:

Linda J. Shore-Lesserson, MD, Lawrence T. Goodnough, MD, C. David Mazer, MD,

Aryeh Shander, MD, Mark Stafford-Smith, MD, and Jonathan Waters, MD

The International Consortium for Evidence Based Perfusion:

Robert A. Baker, PhD, Dip Perf, CCP (Aus), Timothy A. Dickinson, MS,

Daniel J. FitzGerald, CCP, LP, Donald S. Likosky, PhD, and Kenneth G. Shann, CCP

Division of Cardiovascular and Thoracic Surgery, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky (VAF, SPS), Department of

Anesthesiology, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (JW), Departments of Anesthesiology and Critical

Care Medicine, Englewood Hospital and Medical Center, Englewood, New Jersey (AS), Departments of Pathology and Medicine,

Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, California (LTG), Departments of Anesthesiology and Cardiothoracic Surgery,

Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, New York (LJS-L, KGS), Departments of Anesthesiology, Immunology, and Pathology, Washington

University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri (GJD), Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, Section of

Cardiology, Dartmouth Medical School, Lebanon, New Hampshire (JRB), Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Wake Forest School of

Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina (JWH), Department of Anesthesia, St. Michael’s Hospital, University of Toronto, Toronto,

Ontario (CDM), Cardiac Surgical Research Group, Flinders Medical Centre, South Australia, Australia (RAB), Department of Surgery,

Medicine, Community and Family Medicine, and the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, Dartmouth Medical

School, Hanover, New Hampshire (DSL), SpecialtyCare, Nashville, Tennessee (TAD), Department of Cardiac Surgery, Brigham and

Women’s Hospital, Harvard University, Boston, Massachusetts (DJF), Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Oregon Health and Science

University Medical Center, Portland, Oregon (HKS), Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, University of Colorado Health Sciences

Center, Aurora, Colorado (TBR), Department of Anesthesiology, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina (MS-S), and

The Society of Thoracic Surgeons, Chicago, Illinois (ERC)

Background. Practice guidelines reflect published liter- Methods. The search methods used in the current

pro-

bolic

ports

with

213].

t re-

lica-

that

om-

g, or

per-

ICU

Two

ship

pa-

volv-

diac

tar-

mbo-

able [227], and addition of factor concentrates augments

multiple other interventions. Fractionated factor concen-

trates, like factor IX concentrates or one of its various

forms (Beriplex or factor VIII inhibitor bypassing activ-

ity), are considered “secondary components” and may be

acceptable to some Jehovah’s Witness patients [222].

Addition of factor IX concentrates may be most useful in

the highest risk Jehovah’s Witness patients.

d) Blood Salvage Interventions

EXPANDED USE OF RED CELL SALVAGE USING CENTRIFUGATION

Class IIb.

1. In high-risk patients with known malignancy who

require CPB, blood salvage using centrifugation of

blood salvaged from the operative field may be

considered since substantial data support benefit in

patients without malignancy, and new evidence

suggests worsened outcome when allogeneic trans-

fusion is required in patients with malignancy.

(Level of evidence B)

In 1986, the American Medical Association Council on

Scientific Affairs issued a statement regarding the safety

of blood salvage during cancer surgery [228]. At that

time, they advised against its use. Since then, 10 obser-

vational studies that included 476 patients who received

blood salvage during resection of multiple different tumor

types involving the liver [229–231], prostate [232–234],

uterus [235, 236], and urologic system [237, 238] support the

use of salvage of red cells using centrifugation in cancer

patients. In seven studies, a control group received no

transfusion, allogeneic transfusion, or preoperative autolo-

end of CPB is reasonable as part of a bl

agement program to minimize blood tr

(Level of evidence C)

2. Centrifugation instead of direct infusion o

pump blood is reasonable for minimizing

allogeneic RBC transfusion. (Level of evi

Most surgical teams reinfuse blood from t

poreal circuit (ECC) back into patients at the

as part of a blood conservation strategy. Cu

blood salvaging techniques exist: (1) direct

post-CPB circuit blood with no processing;

cessing of the circuit blood, either by centrifu

ultrafiltration, to remove either plasma com

water soluble components from blood before

Ann Thorac Surg FERRARIS

2011;91:944–82 STS BLOOD CONSERVATION REVISION

10 studi osservazionali su 476 pazienti

operati per diverse patologie tumorali

supportano l’uso del cell saver

mercoledì 26 novembre 14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romaint-160320122837/85/A-fresh-look-at-cell-salvage-55-320.jpg)

![2011 Update to The Society of Thoracic Surgeons

and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists

Blood Conservation Clinical Practice Guidelines*

The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Blood Conservation Guideline Task Force:

Victor A. Ferraris, MD, PhD (Chair), Jeremiah R. Brown, PhD, George J. Despotis, MD,

John W. Hammon, MD, T. Brett Reece, MD, Sibu P. Saha, MD, MBA,

Howard K. Song, MD, PhD, and Ellen R. Clough, PhD

The Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists Special Task Force on Blood Transfusion:

Linda J. Shore-Lesserson, MD, Lawrence T. Goodnough, MD, C. David Mazer, MD,

Aryeh Shander, MD, Mark Stafford-Smith, MD, and Jonathan Waters, MD

The International Consortium for Evidence Based Perfusion:

Robert A. Baker, PhD, Dip Perf, CCP (Aus), Timothy A. Dickinson, MS,

Daniel J. FitzGerald, CCP, LP, Donald S. Likosky, PhD, and Kenneth G. Shann, CCP

Division of Cardiovascular and Thoracic Surgery, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky (VAF, SPS), Department of

Anesthesiology, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (JW), Departments of Anesthesiology and Critical

Care Medicine, Englewood Hospital and Medical Center, Englewood, New Jersey (AS), Departments of Pathology and Medicine,

Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, California (LTG), Departments of Anesthesiology and Cardiothoracic Surgery,

Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, New York (LJS-L, KGS), Departments of Anesthesiology, Immunology, and Pathology, Washington

University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri (GJD), Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, Section of

Cardiology, Dartmouth Medical School, Lebanon, New Hampshire (JRB), Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Wake Forest School of

Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina (JWH), Department of Anesthesia, St. Michael’s Hospital, University of Toronto, Toronto,

Ontario (CDM), Cardiac Surgical Research Group, Flinders Medical Centre, South Australia, Australia (RAB), Department of Surgery,

Medicine, Community and Family Medicine, and the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, Dartmouth Medical

School, Hanover, New Hampshire (DSL), SpecialtyCare, Nashville, Tennessee (TAD), Department of Cardiac Surgery, Brigham and

Women’s Hospital, Harvard University, Boston, Massachusetts (DJF), Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Oregon Health and Science

University Medical Center, Portland, Oregon (HKS), Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, University of Colorado Health Sciences

Center, Aurora, Colorado (TBR), Department of Anesthesiology, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina (MS-S), and

The Society of Thoracic Surgeons, Chicago, Illinois (ERC)

Background. Practice guidelines reflect published liter- Methods. The search methods used in the current

pro-

bolic

ports

with

213].

t re-

lica-

that

om-

g, or

per-

ICU

Two

ship

pa-

volv-

diac

tar-

mbo-

able [227], and addition of factor concentrates augments

multiple other interventions. Fractionated factor concen-

trates, like factor IX concentrates or one of its various

forms (Beriplex or factor VIII inhibitor bypassing activ-

ity), are considered “secondary components” and may be

acceptable to some Jehovah’s Witness patients [222].

Addition of factor IX concentrates may be most useful in

the highest risk Jehovah’s Witness patients.

d) Blood Salvage Interventions

EXPANDED USE OF RED CELL SALVAGE USING CENTRIFUGATION

Class IIb.

1. In high-risk patients with known malignancy who

require CPB, blood salvage using centrifugation of

blood salvaged from the operative field may be

considered since substantial data support benefit in

patients without malignancy, and new evidence

suggests worsened outcome when allogeneic trans-

fusion is required in patients with malignancy.

(Level of evidence B)

In 1986, the American Medical Association Council on

Scientific Affairs issued a statement regarding the safety

of blood salvage during cancer surgery [228]. At that

time, they advised against its use. Since then, 10 obser-

vational studies that included 476 patients who received

blood salvage during resection of multiple different tumor

types involving the liver [229–231], prostate [232–234],

uterus [235, 236], and urologic system [237, 238] support the

use of salvage of red cells using centrifugation in cancer

patients. In seven studies, a control group received no

transfusion, allogeneic transfusion, or preoperative autolo-

end of CPB is reasonable as part of a bl

agement program to minimize blood tr

(Level of evidence C)

2. Centrifugation instead of direct infusion o

pump blood is reasonable for minimizing

allogeneic RBC transfusion. (Level of evi

Most surgical teams reinfuse blood from t

poreal circuit (ECC) back into patients at the

as part of a blood conservation strategy. Cu

blood salvaging techniques exist: (1) direct

post-CPB circuit blood with no processing;

cessing of the circuit blood, either by centrifu

ultrafiltration, to remove either plasma com

water soluble components from blood before

Ann Thorac Surg FERRARIS

2011;91:944–82 STS BLOOD CONSERVATION REVISION

10 studi osservazionali su 476 pazienti

operati per diverse patologie tumorali

supportano l’uso del cell saver

mercoledì 26 novembre 14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romaint-160320122837/85/A-fresh-look-at-cell-salvage-56-320.jpg)

![2011 Update to The Society of Thoracic Surgeons

and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists

Blood Conservation Clinical Practice Guidelines*

The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Blood Conservation Guideline Task Force:

Victor A. Ferraris, MD, PhD (Chair), Jeremiah R. Brown, PhD, George J. Despotis, MD,

John W. Hammon, MD, T. Brett Reece, MD, Sibu P. Saha, MD, MBA,

Howard K. Song, MD, PhD, and Ellen R. Clough, PhD

The Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists Special Task Force on Blood Transfusion:

Linda J. Shore-Lesserson, MD, Lawrence T. Goodnough, MD, C. David Mazer, MD,

Aryeh Shander, MD, Mark Stafford-Smith, MD, and Jonathan Waters, MD

The International Consortium for Evidence Based Perfusion:

Robert A. Baker, PhD, Dip Perf, CCP (Aus), Timothy A. Dickinson, MS,

Daniel J. FitzGerald, CCP, LP, Donald S. Likosky, PhD, and Kenneth G. Shann, CCP

Division of Cardiovascular and Thoracic Surgery, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky (VAF, SPS), Department of

Anesthesiology, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (JW), Departments of Anesthesiology and Critical

Care Medicine, Englewood Hospital and Medical Center, Englewood, New Jersey (AS), Departments of Pathology and Medicine,

Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, California (LTG), Departments of Anesthesiology and Cardiothoracic Surgery,

Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, New York (LJS-L, KGS), Departments of Anesthesiology, Immunology, and Pathology, Washington

University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri (GJD), Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, Section of

Cardiology, Dartmouth Medical School, Lebanon, New Hampshire (JRB), Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Wake Forest School of

Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina (JWH), Department of Anesthesia, St. Michael’s Hospital, University of Toronto, Toronto,

Ontario (CDM), Cardiac Surgical Research Group, Flinders Medical Centre, South Australia, Australia (RAB), Department of Surgery,

Medicine, Community and Family Medicine, and the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, Dartmouth Medical

School, Hanover, New Hampshire (DSL), SpecialtyCare, Nashville, Tennessee (TAD), Department of Cardiac Surgery, Brigham and

Women’s Hospital, Harvard University, Boston, Massachusetts (DJF), Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Oregon Health and Science

University Medical Center, Portland, Oregon (HKS), Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, University of Colorado Health Sciences

Center, Aurora, Colorado (TBR), Department of Anesthesiology, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina (MS-S), and

The Society of Thoracic Surgeons, Chicago, Illinois (ERC)

Background. Practice guidelines reflect published liter- Methods. The search methods used in the current

pro-

bolic

ports

with

213].

t re-

lica-

that

om-

g, or

per-

ICU

Two

ship

pa-

volv-

diac

tar-

mbo-

able [227], and addition of factor concentrates augments

multiple other interventions. Fractionated factor concen-

trates, like factor IX concentrates or one of its various

forms (Beriplex or factor VIII inhibitor bypassing activ-

ity), are considered “secondary components” and may be

acceptable to some Jehovah’s Witness patients [222].

Addition of factor IX concentrates may be most useful in

the highest risk Jehovah’s Witness patients.

d) Blood Salvage Interventions

EXPANDED USE OF RED CELL SALVAGE USING CENTRIFUGATION

Class IIb.

1. In high-risk patients with known malignancy who

require CPB, blood salvage using centrifugation of

blood salvaged from the operative field may be

considered since substantial data support benefit in

patients without malignancy, and new evidence

suggests worsened outcome when allogeneic trans-

fusion is required in patients with malignancy.

(Level of evidence B)

In 1986, the American Medical Association Council on

Scientific Affairs issued a statement regarding the safety

of blood salvage during cancer surgery [228]. At that

time, they advised against its use. Since then, 10 obser-

vational studies that included 476 patients who received

blood salvage during resection of multiple different tumor

types involving the liver [229–231], prostate [232–234],

uterus [235, 236], and urologic system [237, 238] support the

use of salvage of red cells using centrifugation in cancer

patients. In seven studies, a control group received no

transfusion, allogeneic transfusion, or preoperative autolo-

end of CPB is reasonable as part of a bl

agement program to minimize blood tr

(Level of evidence C)

2. Centrifugation instead of direct infusion o

pump blood is reasonable for minimizing

allogeneic RBC transfusion. (Level of evi

Most surgical teams reinfuse blood from t

poreal circuit (ECC) back into patients at the

as part of a blood conservation strategy. Cu

blood salvaging techniques exist: (1) direct

post-CPB circuit blood with no processing;

cessing of the circuit blood, either by centrifu

ultrafiltration, to remove either plasma com

water soluble components from blood before

Ann Thorac Surg FERRARIS

2011;91:944–82 STS BLOOD CONSERVATION REVISION

10 studi osservazionali su 476 pazienti

operati per diverse patologie tumorali

supportano l’uso del cell saver

molti reports indicano che i

pazienti che hanno ricevuto

trasfusioni allogeniche hanno un

maggior rischio di recidiva

mercoledì 26 novembre 14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romaint-160320122837/85/A-fresh-look-at-cell-salvage-57-320.jpg)

![2011 Update to The Society of Thoracic Surgeons

and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists

Blood Conservation Clinical Practice Guidelines*

The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Blood Conservation Guideline Task Force:

Victor A. Ferraris, MD, PhD (Chair), Jeremiah R. Brown, PhD, George J. Despotis, MD,

John W. Hammon, MD, T. Brett Reece, MD, Sibu P. Saha, MD, MBA,

Howard K. Song, MD, PhD, and Ellen R. Clough, PhD

The Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists Special Task Force on Blood Transfusion:

Linda J. Shore-Lesserson, MD, Lawrence T. Goodnough, MD, C. David Mazer, MD,

Aryeh Shander, MD, Mark Stafford-Smith, MD, and Jonathan Waters, MD

The International Consortium for Evidence Based Perfusion:

Robert A. Baker, PhD, Dip Perf, CCP (Aus), Timothy A. Dickinson, MS,

Daniel J. FitzGerald, CCP, LP, Donald S. Likosky, PhD, and Kenneth G. Shann, CCP

Division of Cardiovascular and Thoracic Surgery, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky (VAF, SPS), Department of

Anesthesiology, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (JW), Departments of Anesthesiology and Critical

Care Medicine, Englewood Hospital and Medical Center, Englewood, New Jersey (AS), Departments of Pathology and Medicine,

Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, California (LTG), Departments of Anesthesiology and Cardiothoracic Surgery,

Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, New York (LJS-L, KGS), Departments of Anesthesiology, Immunology, and Pathology, Washington

University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri (GJD), Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, Section of

Cardiology, Dartmouth Medical School, Lebanon, New Hampshire (JRB), Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Wake Forest School of

Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina (JWH), Department of Anesthesia, St. Michael’s Hospital, University of Toronto, Toronto,

Ontario (CDM), Cardiac Surgical Research Group, Flinders Medical Centre, South Australia, Australia (RAB), Department of Surgery,

Medicine, Community and Family Medicine, and the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, Dartmouth Medical

School, Hanover, New Hampshire (DSL), SpecialtyCare, Nashville, Tennessee (TAD), Department of Cardiac Surgery, Brigham and

Women’s Hospital, Harvard University, Boston, Massachusetts (DJF), Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Oregon Health and Science

University Medical Center, Portland, Oregon (HKS), Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, University of Colorado Health Sciences

Center, Aurora, Colorado (TBR), Department of Anesthesiology, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina (MS-S), and

The Society of Thoracic Surgeons, Chicago, Illinois (ERC)

Background. Practice guidelines reflect published liter- Methods. The search methods used in the current

pro-

bolic

ports

with

213].

t re-

lica-

that

om-

g, or

per-

ICU

Two

ship

pa-

volv-

diac

tar-

mbo-

able [227], and addition of factor concentrates augments

multiple other interventions. Fractionated factor concen-

trates, like factor IX concentrates or one of its various

forms (Beriplex or factor VIII inhibitor bypassing activ-

ity), are considered “secondary components” and may be

acceptable to some Jehovah’s Witness patients [222].

Addition of factor IX concentrates may be most useful in

the highest risk Jehovah’s Witness patients.

d) Blood Salvage Interventions

EXPANDED USE OF RED CELL SALVAGE USING CENTRIFUGATION

Class IIb.

1. In high-risk patients with known malignancy who

require CPB, blood salvage using centrifugation of

blood salvaged from the operative field may be

considered since substantial data support benefit in

patients without malignancy, and new evidence

suggests worsened outcome when allogeneic trans-

fusion is required in patients with malignancy.

(Level of evidence B)

In 1986, the American Medical Association Council on

Scientific Affairs issued a statement regarding the safety

of blood salvage during cancer surgery [228]. At that

time, they advised against its use. Since then, 10 obser-

vational studies that included 476 patients who received

blood salvage during resection of multiple different tumor

types involving the liver [229–231], prostate [232–234],

uterus [235, 236], and urologic system [237, 238] support the

use of salvage of red cells using centrifugation in cancer

patients. In seven studies, a control group received no

transfusion, allogeneic transfusion, or preoperative autolo-

end of CPB is reasonable as part of a bl

agement program to minimize blood tr

(Level of evidence C)

2. Centrifugation instead of direct infusion o

pump blood is reasonable for minimizing

allogeneic RBC transfusion. (Level of evi

Most surgical teams reinfuse blood from t

poreal circuit (ECC) back into patients at the

as part of a blood conservation strategy. Cu

blood salvaging techniques exist: (1) direct

post-CPB circuit blood with no processing;

cessing of the circuit blood, either by centrifu

ultrafiltration, to remove either plasma com

water soluble components from blood before

Ann Thorac Surg FERRARIS

2011;91:944–82 STS BLOOD CONSERVATION REVISION

10 studi osservazionali su 476 pazienti

operati per diverse patologie tumorali

supportano l’uso del cell saver

molti reports indicano che i

pazienti che hanno ricevuto

trasfusioni allogeniche hanno un

maggior rischio di recidiva

mercoledì 26 novembre 14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romaint-160320122837/85/A-fresh-look-at-cell-salvage-58-320.jpg)

![2011 Update to The Society of Thoracic Surgeons

and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists

Blood Conservation Clinical Practice Guidelines*

The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Blood Conservation Guideline Task Force:

Victor A. Ferraris, MD, PhD (Chair), Jeremiah R. Brown, PhD, George J. Despotis, MD,

John W. Hammon, MD, T. Brett Reece, MD, Sibu P. Saha, MD, MBA,

Howard K. Song, MD, PhD, and Ellen R. Clough, PhD

The Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists Special Task Force on Blood Transfusion:

Linda J. Shore-Lesserson, MD, Lawrence T. Goodnough, MD, C. David Mazer, MD,

Aryeh Shander, MD, Mark Stafford-Smith, MD, and Jonathan Waters, MD

The International Consortium for Evidence Based Perfusion:

Robert A. Baker, PhD, Dip Perf, CCP (Aus), Timothy A. Dickinson, MS,

Daniel J. FitzGerald, CCP, LP, Donald S. Likosky, PhD, and Kenneth G. Shann, CCP

Division of Cardiovascular and Thoracic Surgery, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky (VAF, SPS), Department of

Anesthesiology, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (JW), Departments of Anesthesiology and Critical

Care Medicine, Englewood Hospital and Medical Center, Englewood, New Jersey (AS), Departments of Pathology and Medicine,

Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, California (LTG), Departments of Anesthesiology and Cardiothoracic Surgery,

Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, New York (LJS-L, KGS), Departments of Anesthesiology, Immunology, and Pathology, Washington

University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri (GJD), Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, Section of

Cardiology, Dartmouth Medical School, Lebanon, New Hampshire (JRB), Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Wake Forest School of

Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina (JWH), Department of Anesthesia, St. Michael’s Hospital, University of Toronto, Toronto,

Ontario (CDM), Cardiac Surgical Research Group, Flinders Medical Centre, South Australia, Australia (RAB), Department of Surgery,

Medicine, Community and Family Medicine, and the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, Dartmouth Medical

School, Hanover, New Hampshire (DSL), SpecialtyCare, Nashville, Tennessee (TAD), Department of Cardiac Surgery, Brigham and

Women’s Hospital, Harvard University, Boston, Massachusetts (DJF), Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Oregon Health and Science

University Medical Center, Portland, Oregon (HKS), Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, University of Colorado Health Sciences

Center, Aurora, Colorado (TBR), Department of Anesthesiology, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina (MS-S), and

The Society of Thoracic Surgeons, Chicago, Illinois (ERC)

Background. Practice guidelines reflect published liter- Methods. The search methods used in the current

pro-

bolic

ports

with

213].

t re-

lica-

that

om-

g, or

per-

ICU

Two

ship

pa-

volv-

diac

tar-

mbo-

able [227], and addition of factor concentrates augments

multiple other interventions. Fractionated factor concen-

trates, like factor IX concentrates or one of its various

forms (Beriplex or factor VIII inhibitor bypassing activ-

ity), are considered “secondary components” and may be

acceptable to some Jehovah’s Witness patients [222].

Addition of factor IX concentrates may be most useful in

the highest risk Jehovah’s Witness patients.

d) Blood Salvage Interventions

EXPANDED USE OF RED CELL SALVAGE USING CENTRIFUGATION

Class IIb.

1. In high-risk patients with known malignancy who

require CPB, blood salvage using centrifugation of

blood salvaged from the operative field may be

considered since substantial data support benefit in

patients without malignancy, and new evidence

suggests worsened outcome when allogeneic trans-

fusion is required in patients with malignancy.

(Level of evidence B)

In 1986, the American Medical Association Council on

Scientific Affairs issued a statement regarding the safety

of blood salvage during cancer surgery [228]. At that

time, they advised against its use. Since then, 10 obser-

vational studies that included 476 patients who received

blood salvage during resection of multiple different tumor

types involving the liver [229–231], prostate [232–234],

uterus [235, 236], and urologic system [237, 238] support the

use of salvage of red cells using centrifugation in cancer

patients. In seven studies, a control group received no

transfusion, allogeneic transfusion, or preoperative autolo-

end of CPB is reasonable as part of a bl

agement program to minimize blood tr

(Level of evidence C)

2. Centrifugation instead of direct infusion o

pump blood is reasonable for minimizing

allogeneic RBC transfusion. (Level of evi

Most surgical teams reinfuse blood from t

poreal circuit (ECC) back into patients at the

as part of a blood conservation strategy. Cu

blood salvaging techniques exist: (1) direct

post-CPB circuit blood with no processing;

cessing of the circuit blood, either by centrifu

ultrafiltration, to remove either plasma com

water soluble components from blood before

Ann Thorac Surg FERRARIS

2011;91:944–82 STS BLOOD CONSERVATION REVISION

10 studi osservazionali su 476 pazienti

operati per diverse patologie tumorali

supportano l’uso del cell saver

molti reports indicano che i

pazienti che hanno ricevuto

trasfusioni allogeniche hanno un

maggior rischio di recidiva

due recenti metanalisi

suggeriscono che questo

rischio è doppio

mercoledì 26 novembre 14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romaint-160320122837/85/A-fresh-look-at-cell-salvage-59-320.jpg)

![2011 Update to The Society of Thoracic Surgeons

and the Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists

Blood Conservation Clinical Practice Guidelines*

The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Blood Conservation Guideline Task Force:

Victor A. Ferraris, MD, PhD (Chair), Jeremiah R. Brown, PhD, George J. Despotis, MD,

John W. Hammon, MD, T. Brett Reece, MD, Sibu P. Saha, MD, MBA,

Howard K. Song, MD, PhD, and Ellen R. Clough, PhD

The Society of Cardiovascular Anesthesiologists Special Task Force on Blood Transfusion:

Linda J. Shore-Lesserson, MD, Lawrence T. Goodnough, MD, C. David Mazer, MD,

Aryeh Shander, MD, Mark Stafford-Smith, MD, and Jonathan Waters, MD

The International Consortium for Evidence Based Perfusion:

Robert A. Baker, PhD, Dip Perf, CCP (Aus), Timothy A. Dickinson, MS,

Daniel J. FitzGerald, CCP, LP, Donald S. Likosky, PhD, and Kenneth G. Shann, CCP

Division of Cardiovascular and Thoracic Surgery, University of Kentucky, Lexington, Kentucky (VAF, SPS), Department of

Anesthesiology, University of Pittsburgh Medical Center, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania (JW), Departments of Anesthesiology and Critical

Care Medicine, Englewood Hospital and Medical Center, Englewood, New Jersey (AS), Departments of Pathology and Medicine,

Stanford University School of Medicine, Stanford, California (LTG), Departments of Anesthesiology and Cardiothoracic Surgery,

Montefiore Medical Center, Bronx, New York (LJS-L, KGS), Departments of Anesthesiology, Immunology, and Pathology, Washington

University School of Medicine, St. Louis, Missouri (GJD), Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, Section of

Cardiology, Dartmouth Medical School, Lebanon, New Hampshire (JRB), Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Wake Forest School of

Medicine, Winston-Salem, North Carolina (JWH), Department of Anesthesia, St. Michael’s Hospital, University of Toronto, Toronto,

Ontario (CDM), Cardiac Surgical Research Group, Flinders Medical Centre, South Australia, Australia (RAB), Department of Surgery,

Medicine, Community and Family Medicine, and the Dartmouth Institute for Health Policy and Clinical Practice, Dartmouth Medical

School, Hanover, New Hampshire (DSL), SpecialtyCare, Nashville, Tennessee (TAD), Department of Cardiac Surgery, Brigham and

Women’s Hospital, Harvard University, Boston, Massachusetts (DJF), Division of Cardiothoracic Surgery, Oregon Health and Science

University Medical Center, Portland, Oregon (HKS), Department of Cardiothoracic Surgery, University of Colorado Health Sciences

Center, Aurora, Colorado (TBR), Department of Anesthesiology, Duke University Medical Center, Durham, North Carolina (MS-S), and

The Society of Thoracic Surgeons, Chicago, Illinois (ERC)

Background. Practice guidelines reflect published liter- Methods. The search methods used in the current

pro-

bolic

ports

with

213].

t re-

lica-

that

om-

g, or

per-

ICU

Two

ship

pa-

volv-

diac

tar-

mbo-

able [227], and addition of factor concentrates augments

multiple other interventions. Fractionated factor concen-

trates, like factor IX concentrates or one of its various

forms (Beriplex or factor VIII inhibitor bypassing activ-

ity), are considered “secondary components” and may be

acceptable to some Jehovah’s Witness patients [222].

Addition of factor IX concentrates may be most useful in

the highest risk Jehovah’s Witness patients.

d) Blood Salvage Interventions

EXPANDED USE OF RED CELL SALVAGE USING CENTRIFUGATION

Class IIb.

1. In high-risk patients with known malignancy who

require CPB, blood salvage using centrifugation of

blood salvaged from the operative field may be

considered since substantial data support benefit in

patients without malignancy, and new evidence

suggests worsened outcome when allogeneic trans-

fusion is required in patients with malignancy.

(Level of evidence B)

In 1986, the American Medical Association Council on

Scientific Affairs issued a statement regarding the safety

of blood salvage during cancer surgery [228]. At that

time, they advised against its use. Since then, 10 obser-

vational studies that included 476 patients who received

blood salvage during resection of multiple different tumor

types involving the liver [229–231], prostate [232–234],

uterus [235, 236], and urologic system [237, 238] support the

use of salvage of red cells using centrifugation in cancer

patients. In seven studies, a control group received no

transfusion, allogeneic transfusion, or preoperative autolo-

end of CPB is reasonable as part of a bl

agement program to minimize blood tr

(Level of evidence C)

2. Centrifugation instead of direct infusion o

pump blood is reasonable for minimizing

allogeneic RBC transfusion. (Level of evi

Most surgical teams reinfuse blood from t

poreal circuit (ECC) back into patients at the

as part of a blood conservation strategy. Cu

blood salvaging techniques exist: (1) direct

post-CPB circuit blood with no processing;

cessing of the circuit blood, either by centrifu

ultrafiltration, to remove either plasma com

water soluble components from blood before

Ann Thorac Surg FERRARIS

2011;91:944–82 STS BLOOD CONSERVATION REVISION

10 studi osservazionali su 476 pazienti

operati per diverse patologie tumorali

supportano l’uso del cell saver

molti reports indicano che i

pazienti che hanno ricevuto

trasfusioni allogeniche hanno un

maggior rischio di recidiva

due recenti metanalisi

suggeriscono che questo

rischio è doppio

mercoledì 26 novembre 14](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/romaint-160320122837/85/A-fresh-look-at-cell-salvage-60-320.jpg)