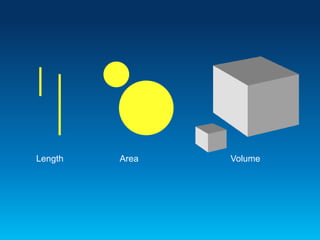

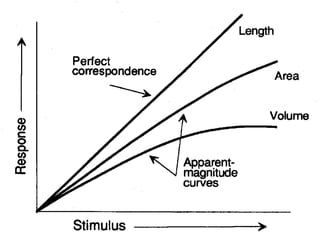

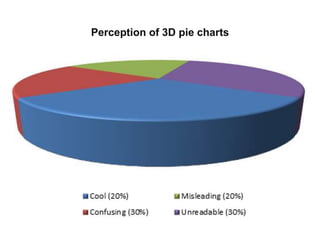

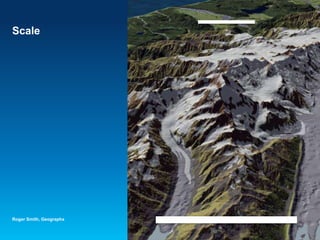

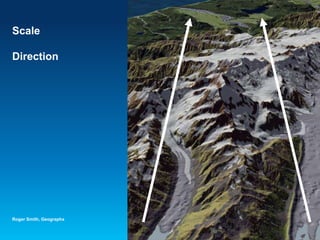

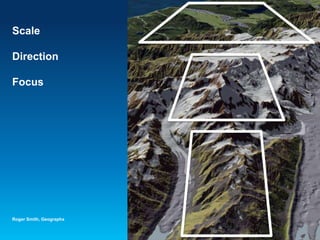

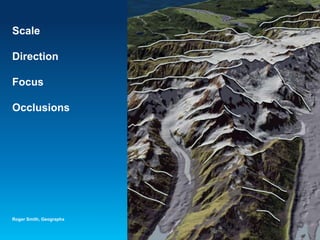

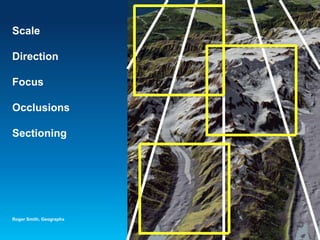

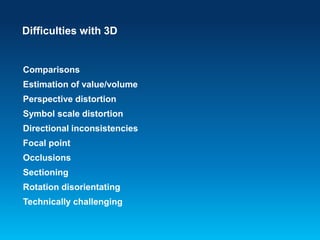

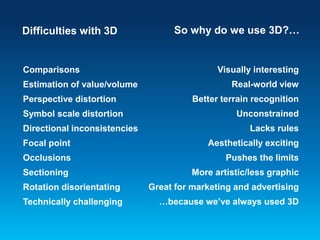

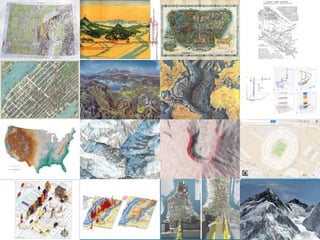

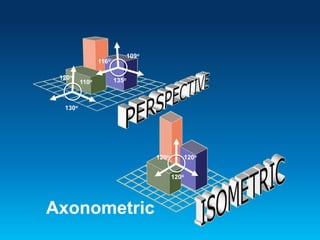

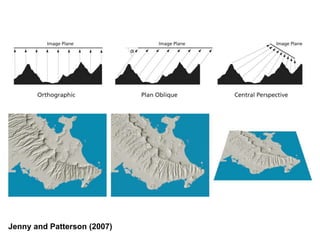

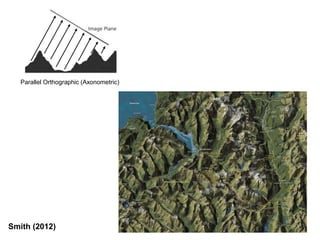

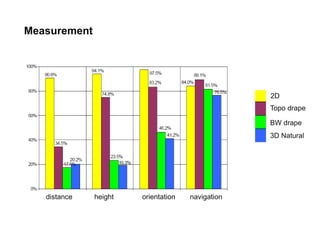

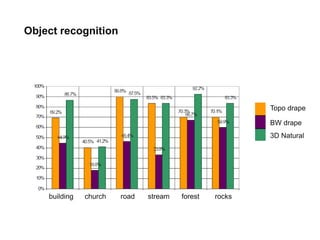

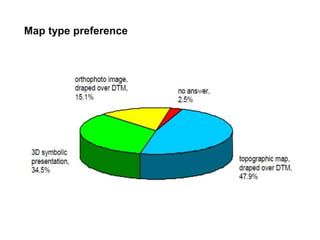

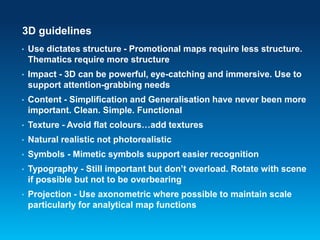

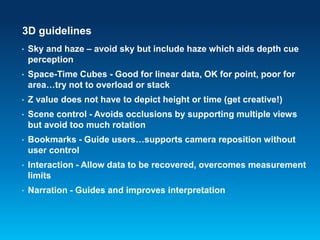

This document discusses 3D cartography and provides guidelines for its effective use. It notes both advantages and disadvantages of 3D maps, including that they can be visually interesting but also technically challenging. The document then outlines several guidelines for 3D maps, such as using them when the third dimension encodes useful information, employing simplification and generalization, avoiding photorealistic textures, and using axonometric projections to maintain scale. It stresses that 3D should only be used when it supports the map purpose and that 2D may be better if the third dimension does not encode something useful.