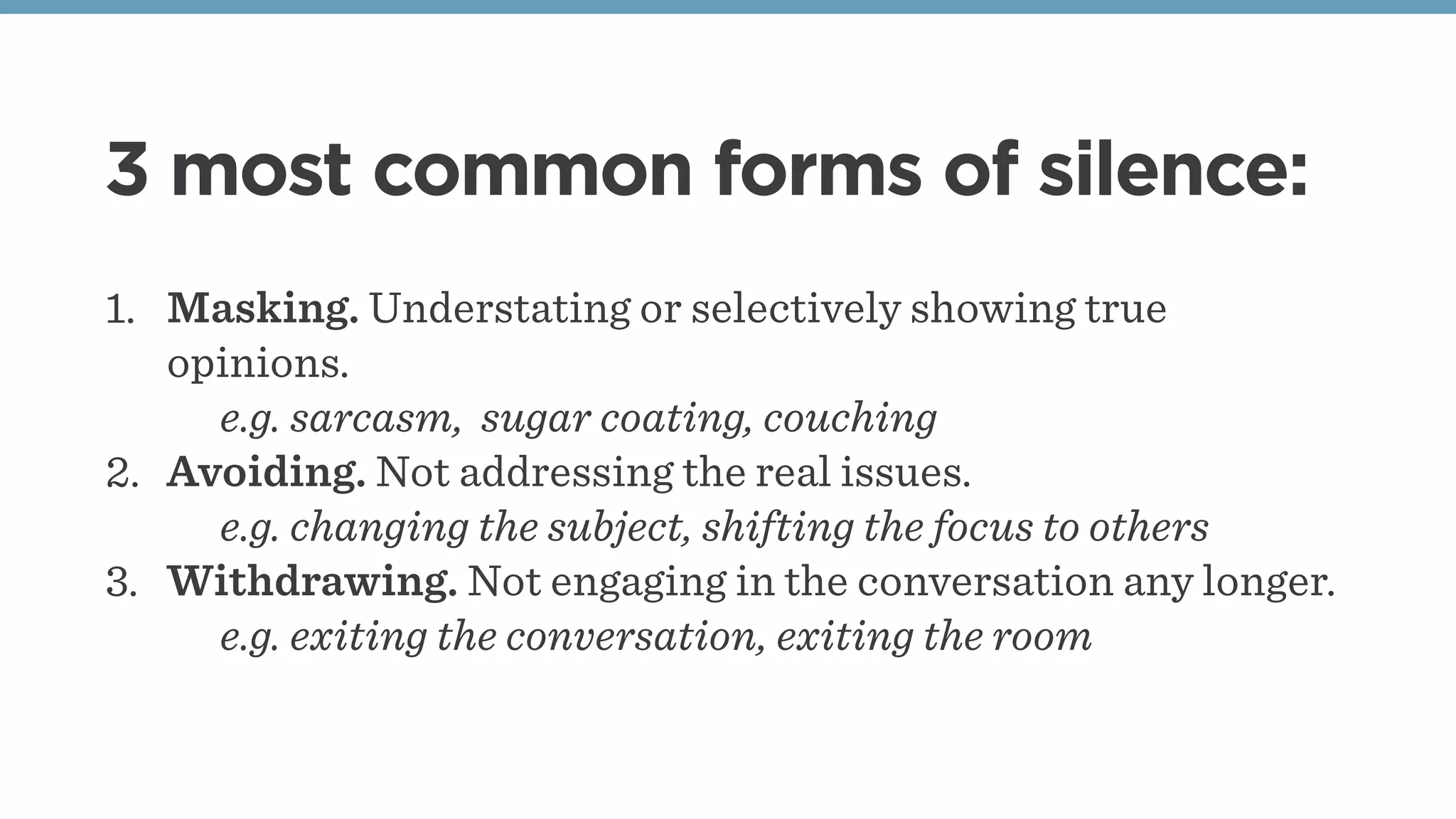

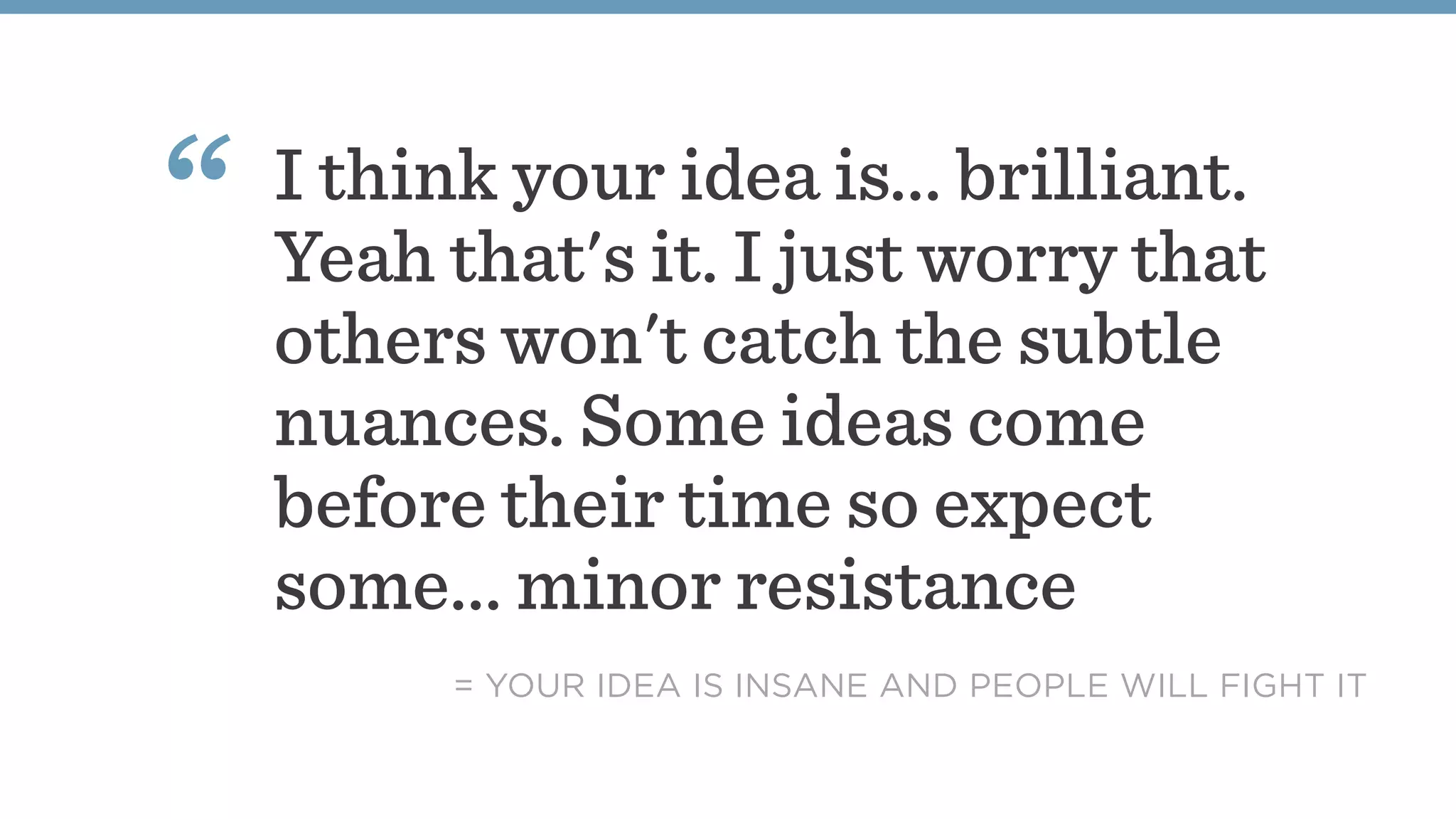

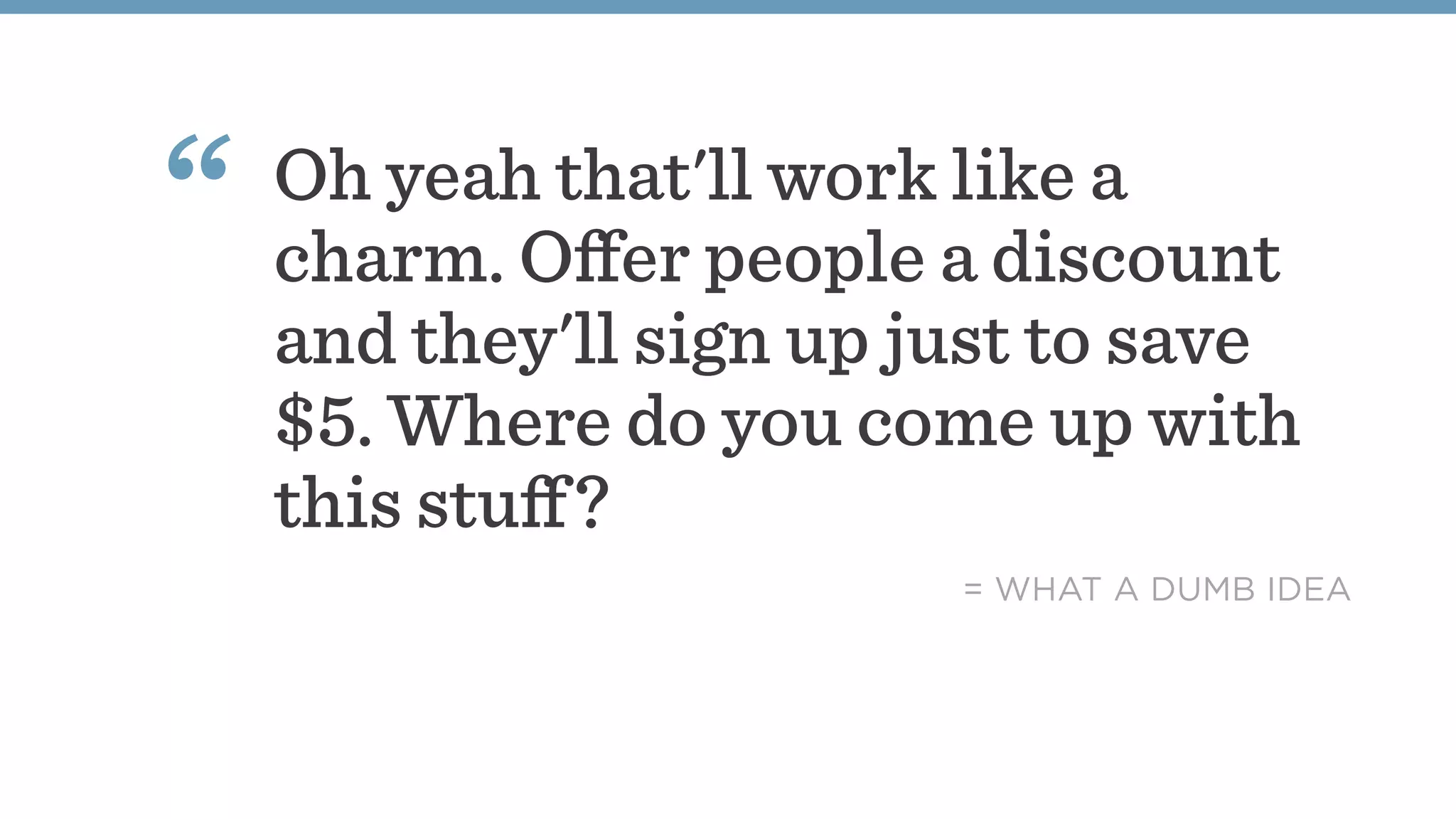

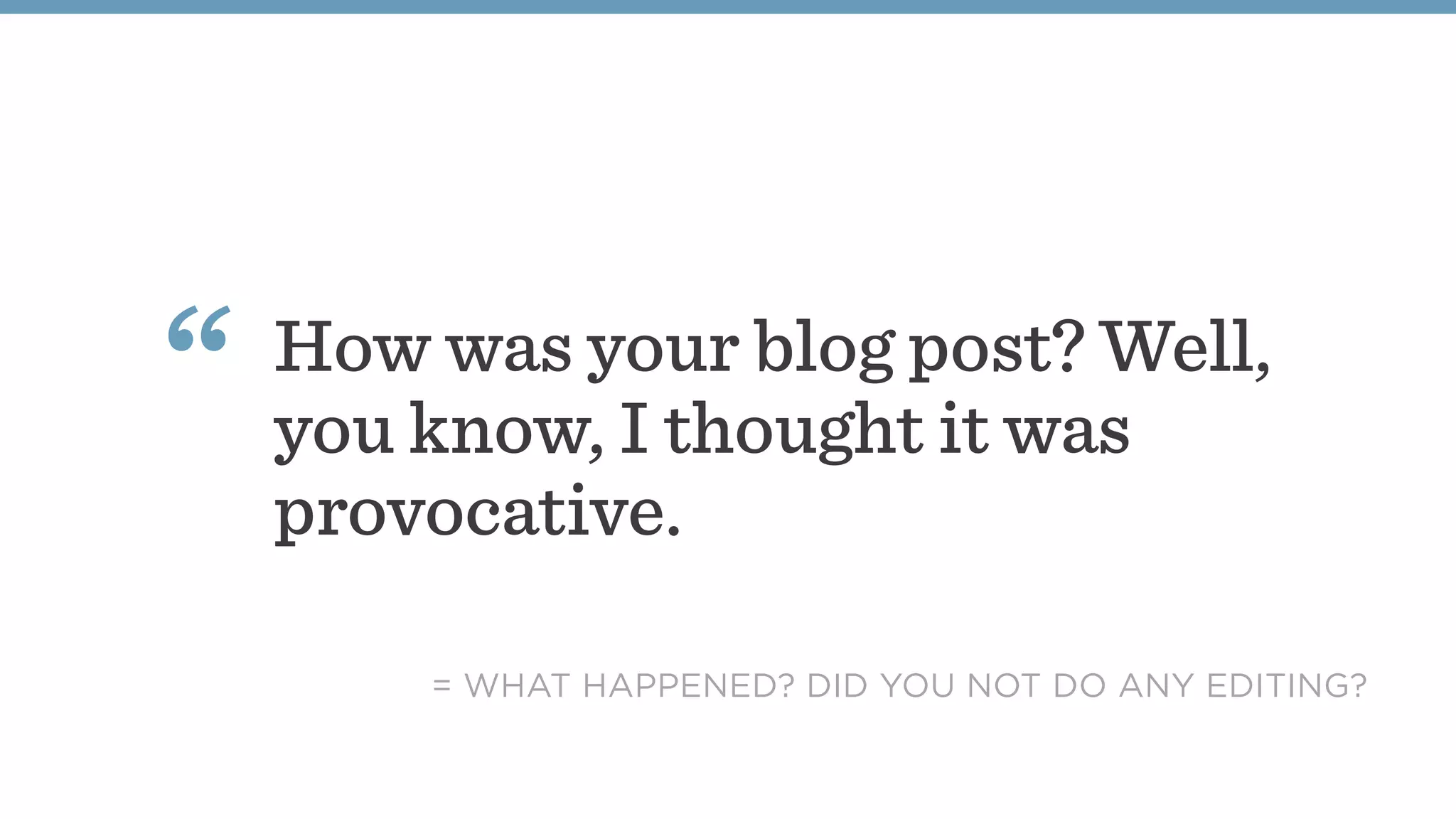

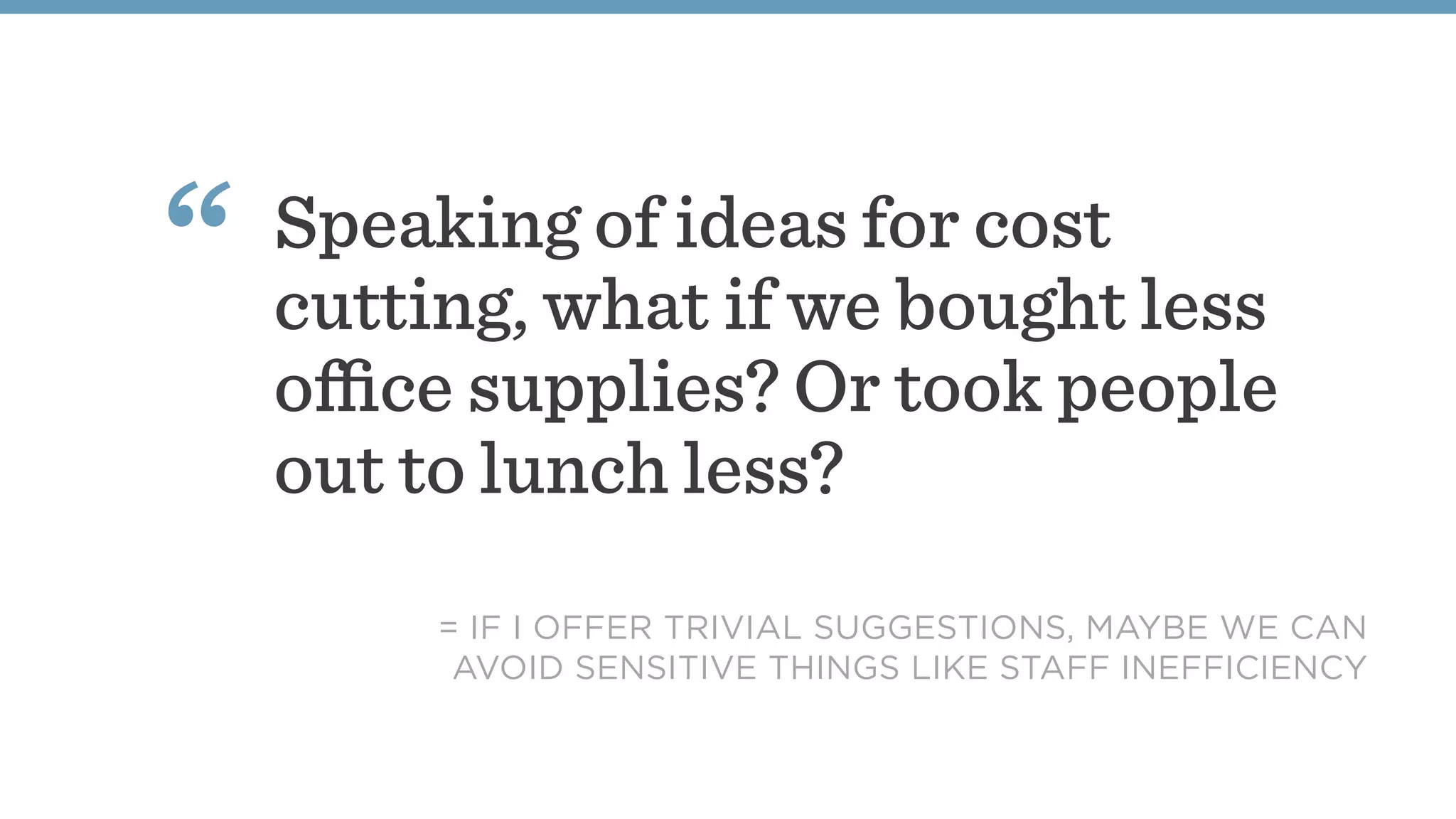

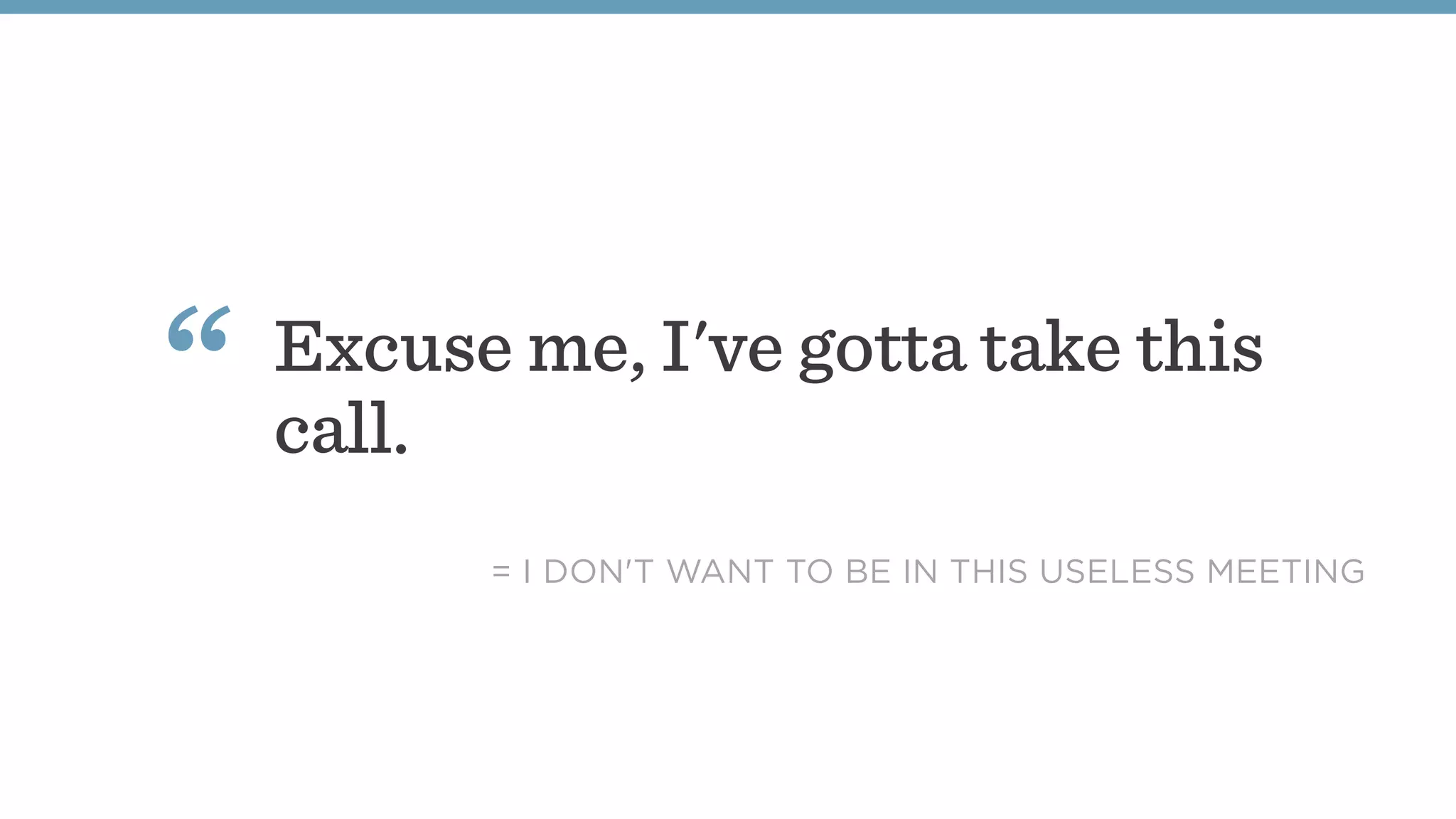

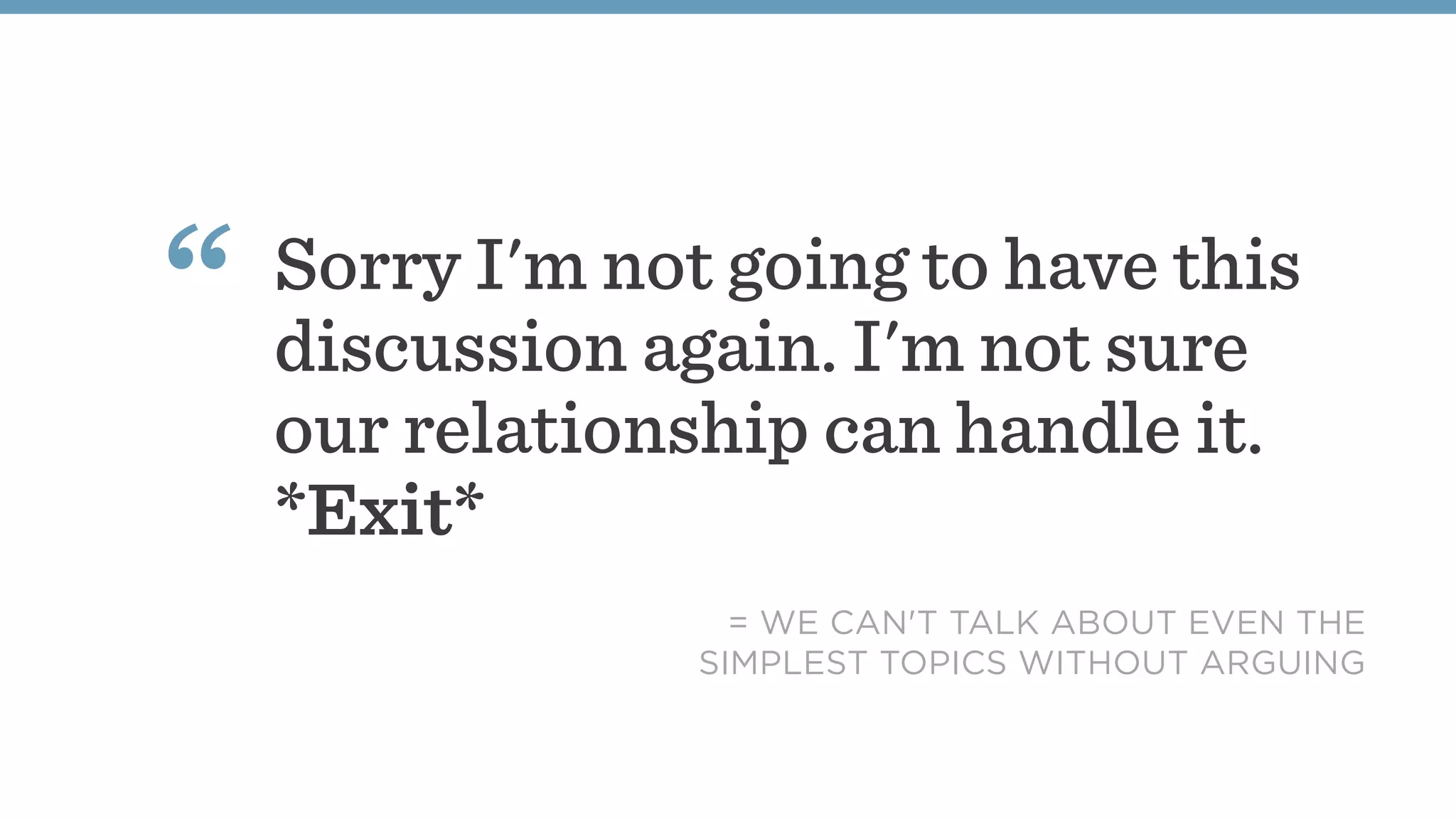

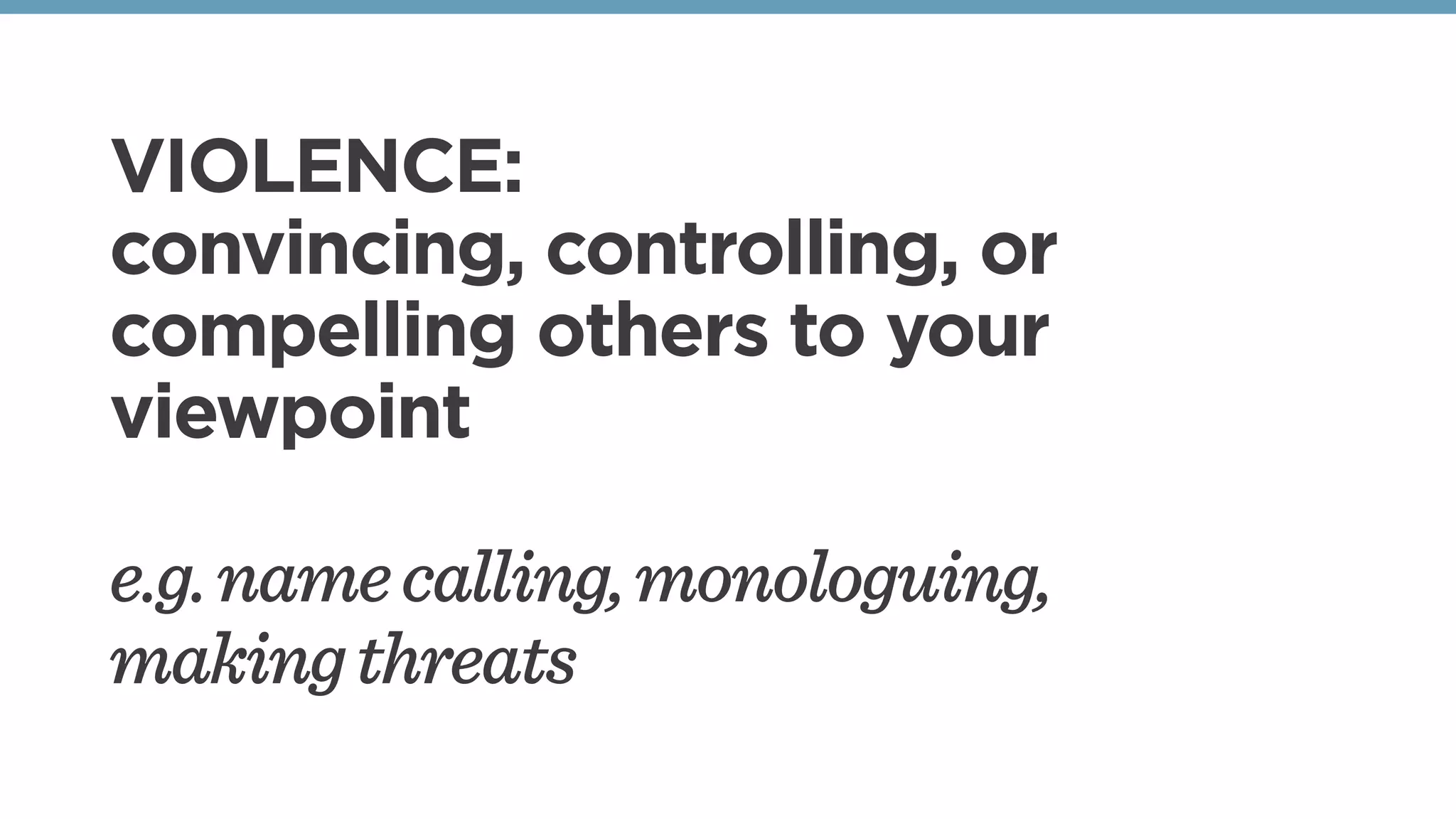

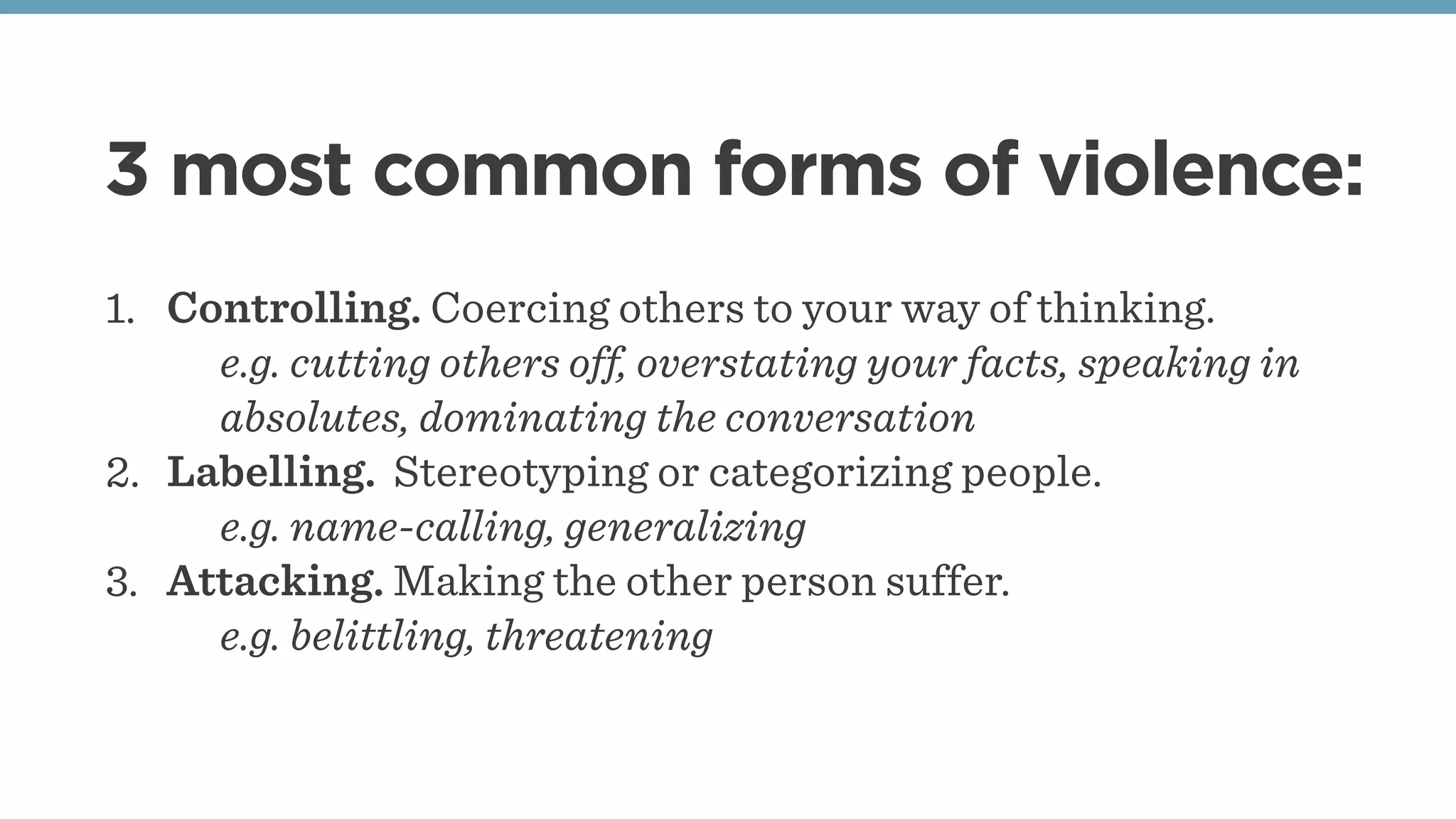

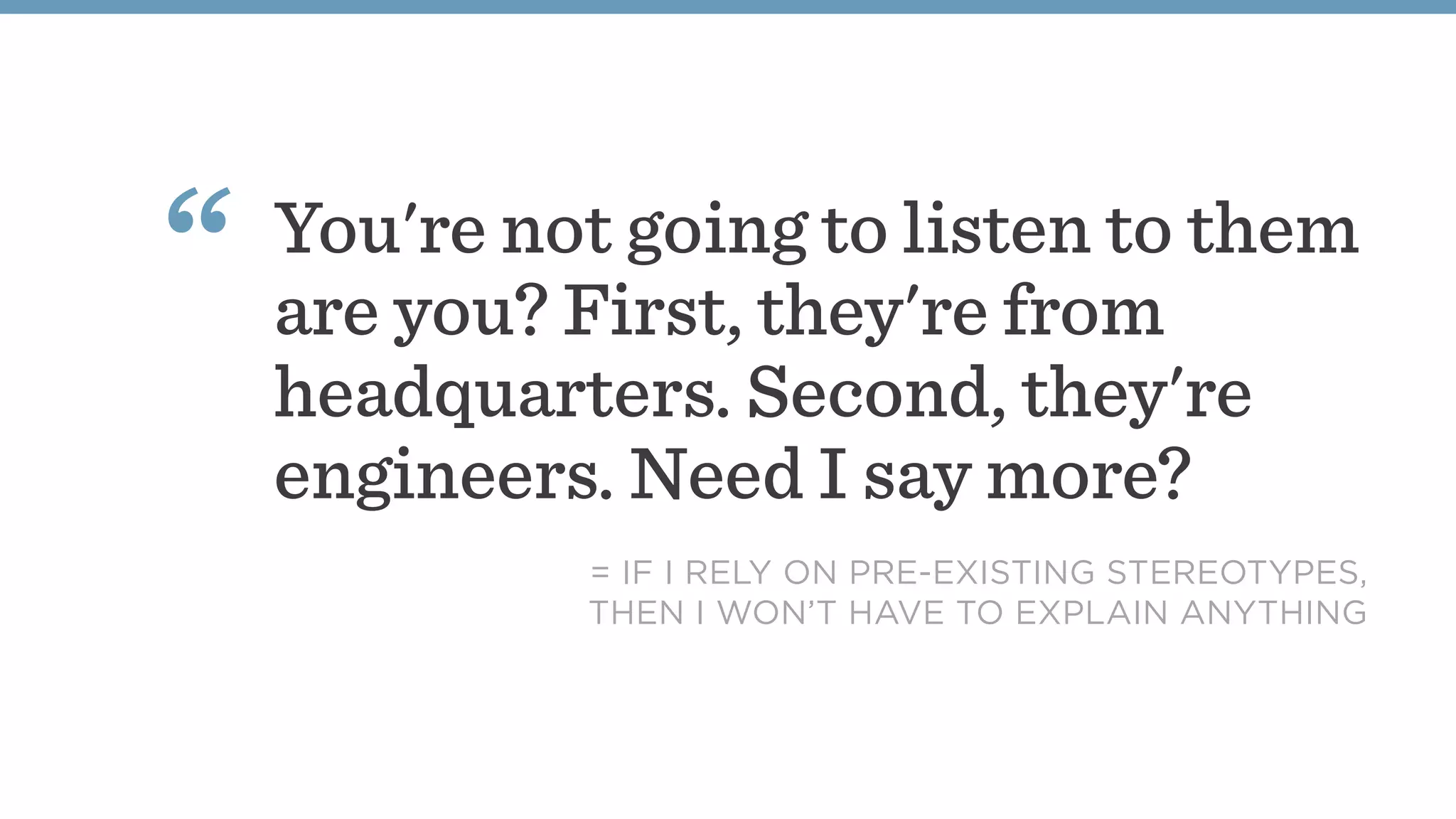

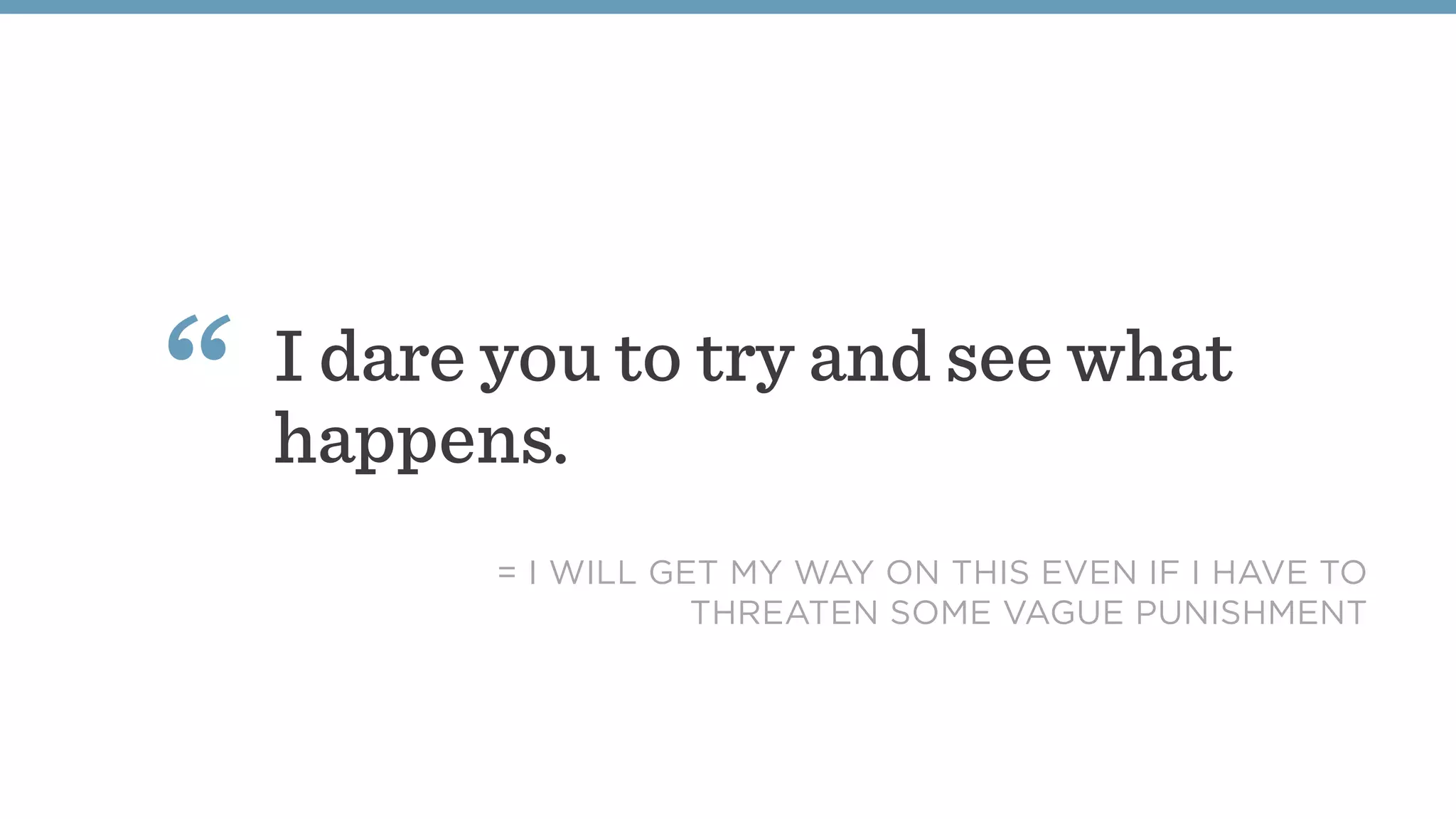

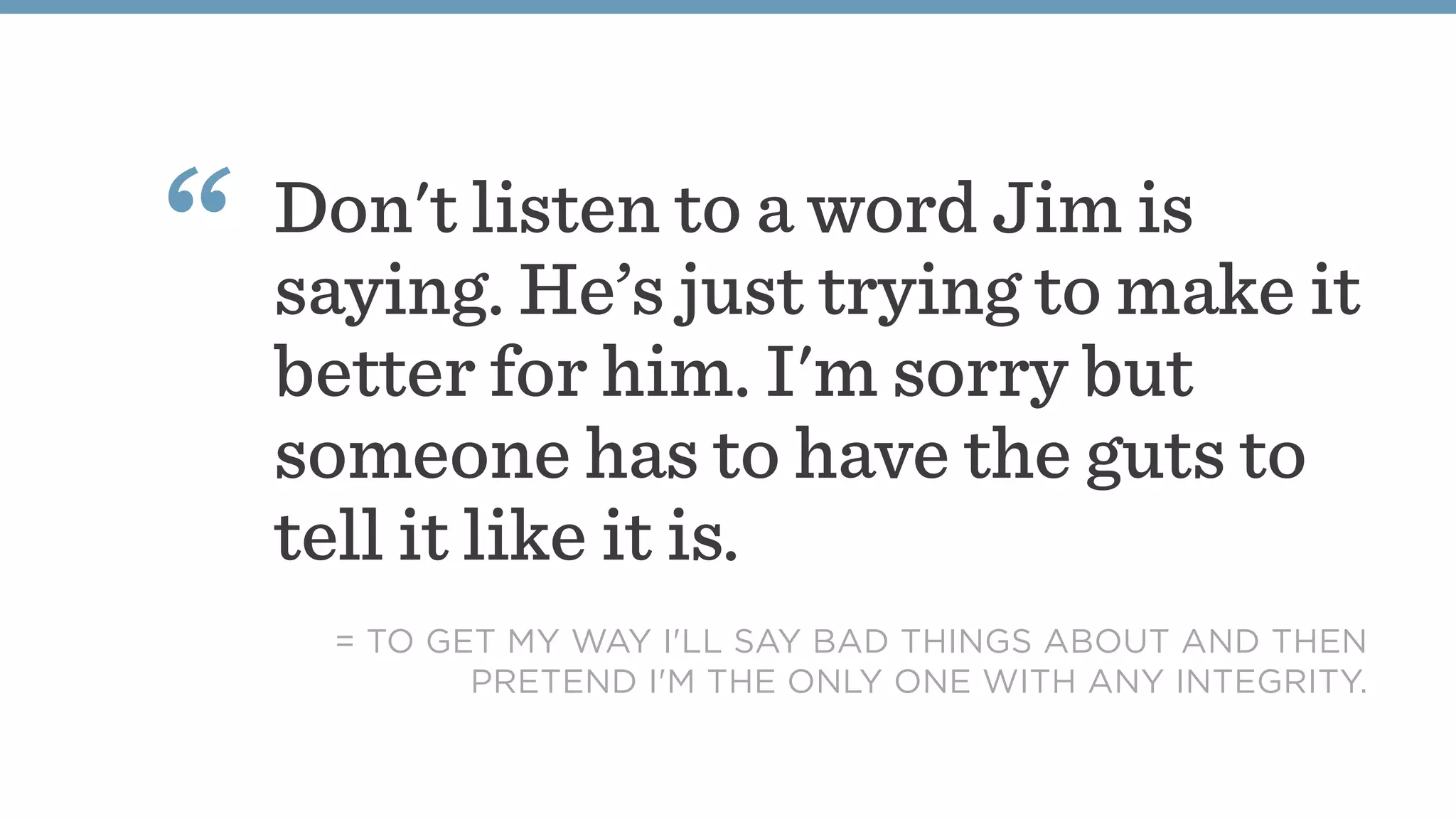

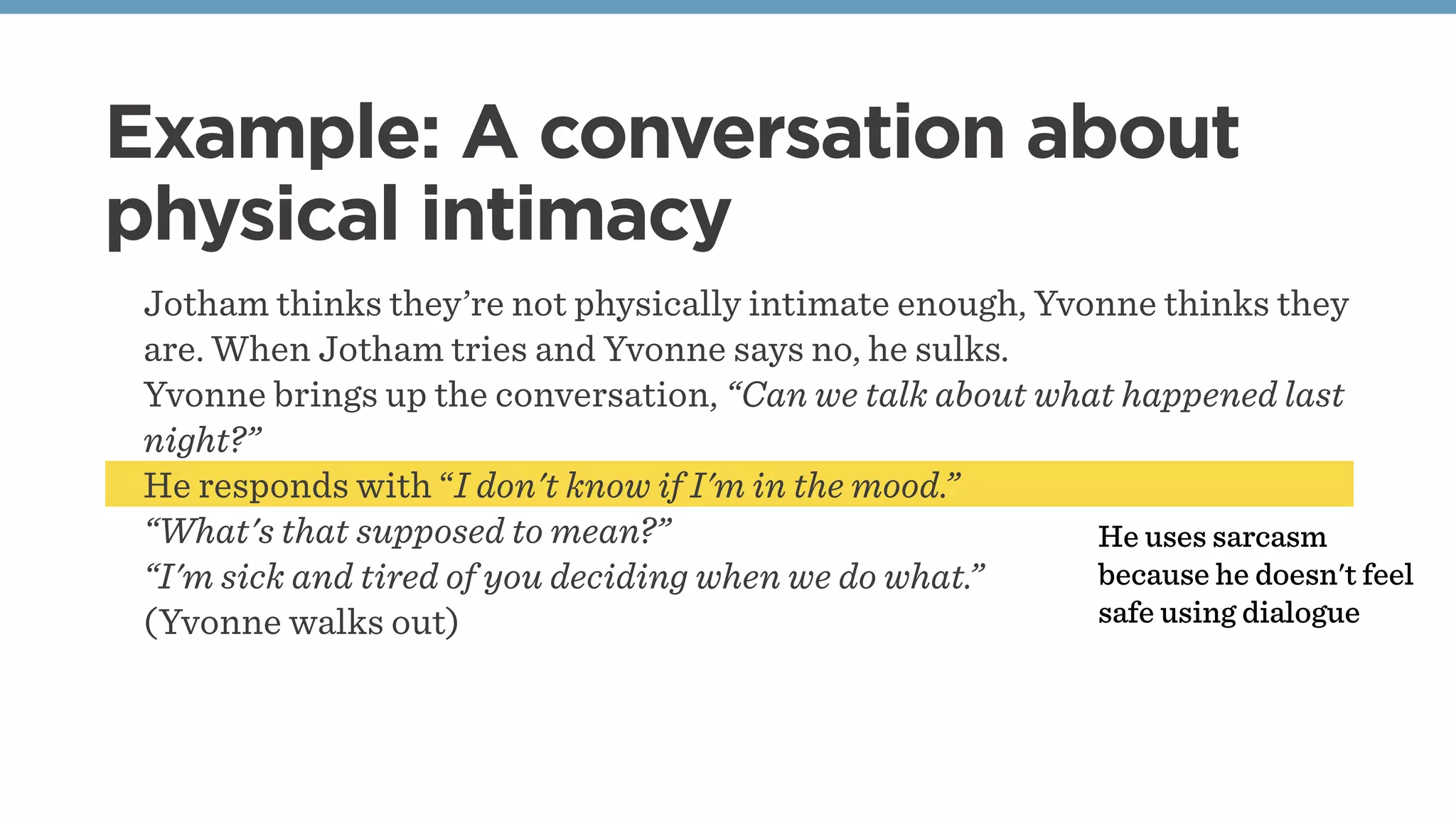

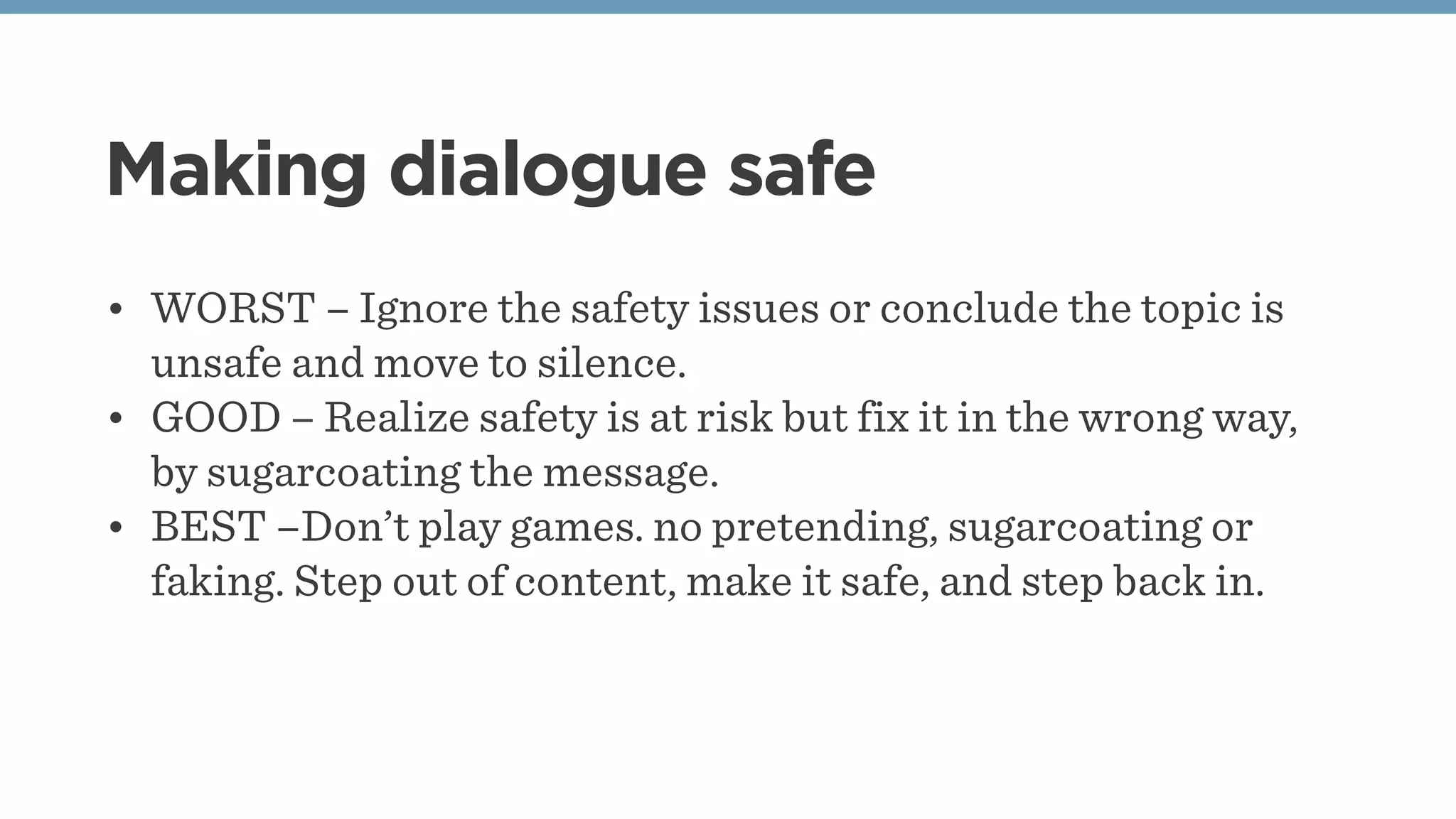

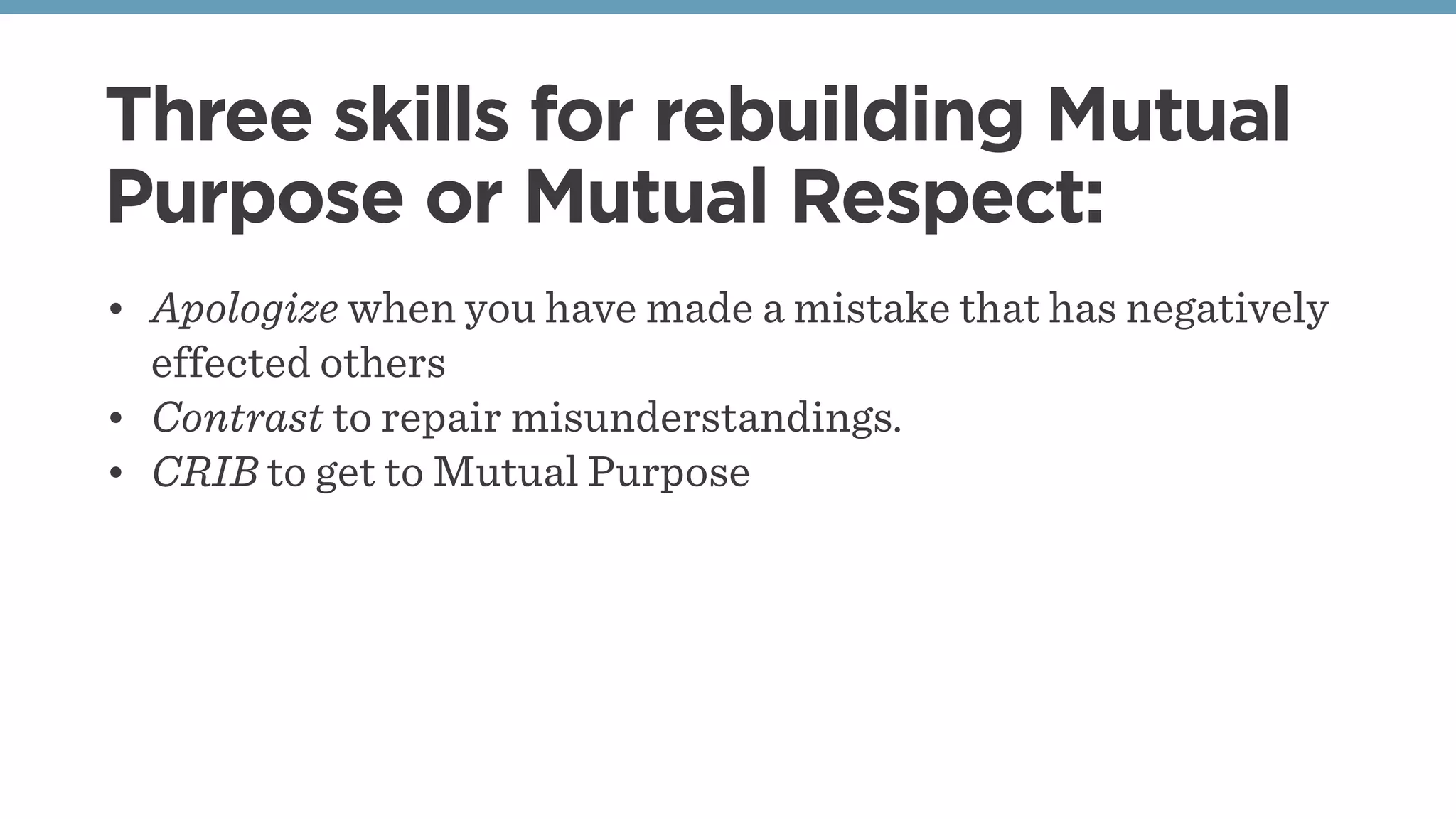

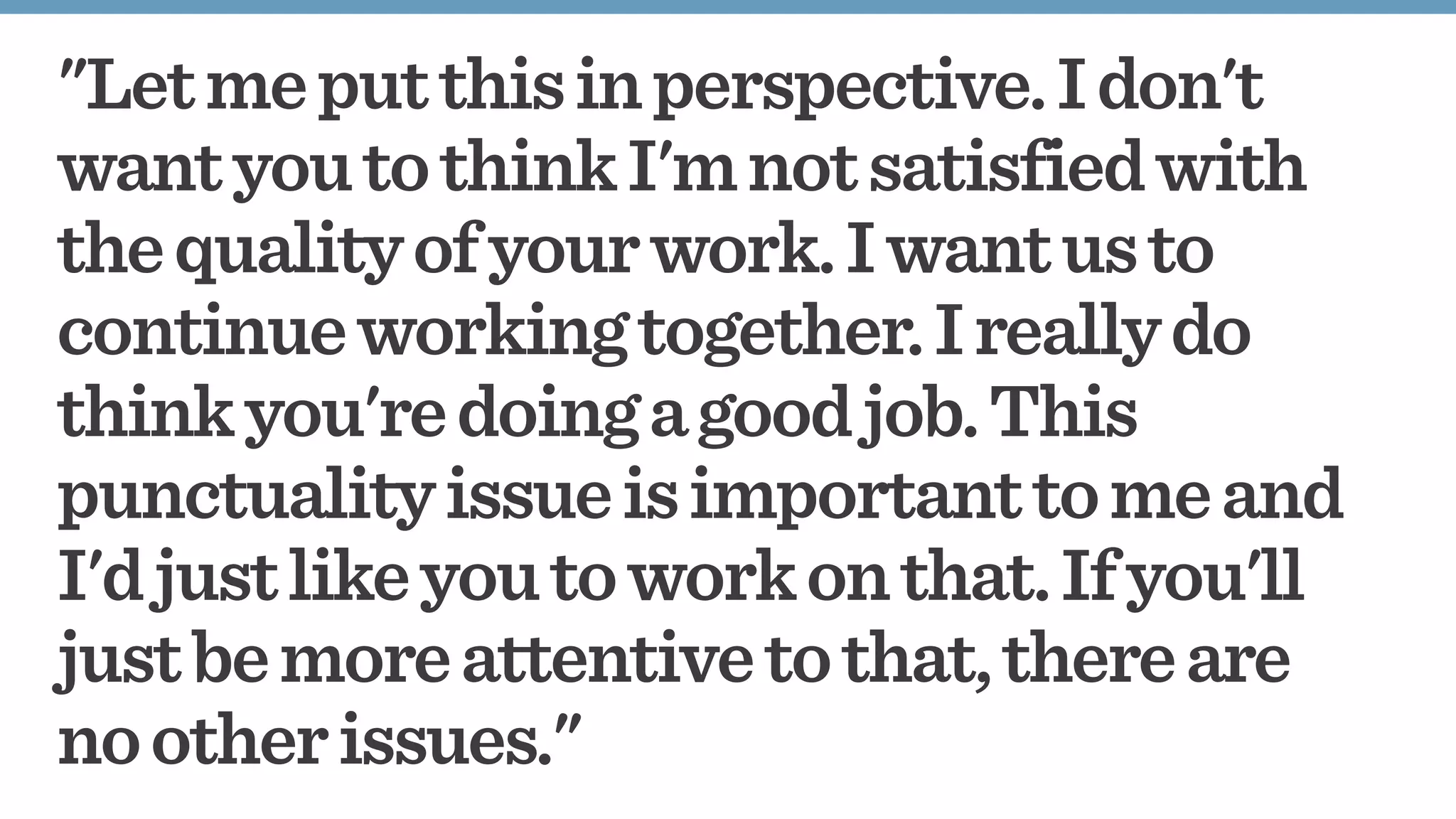

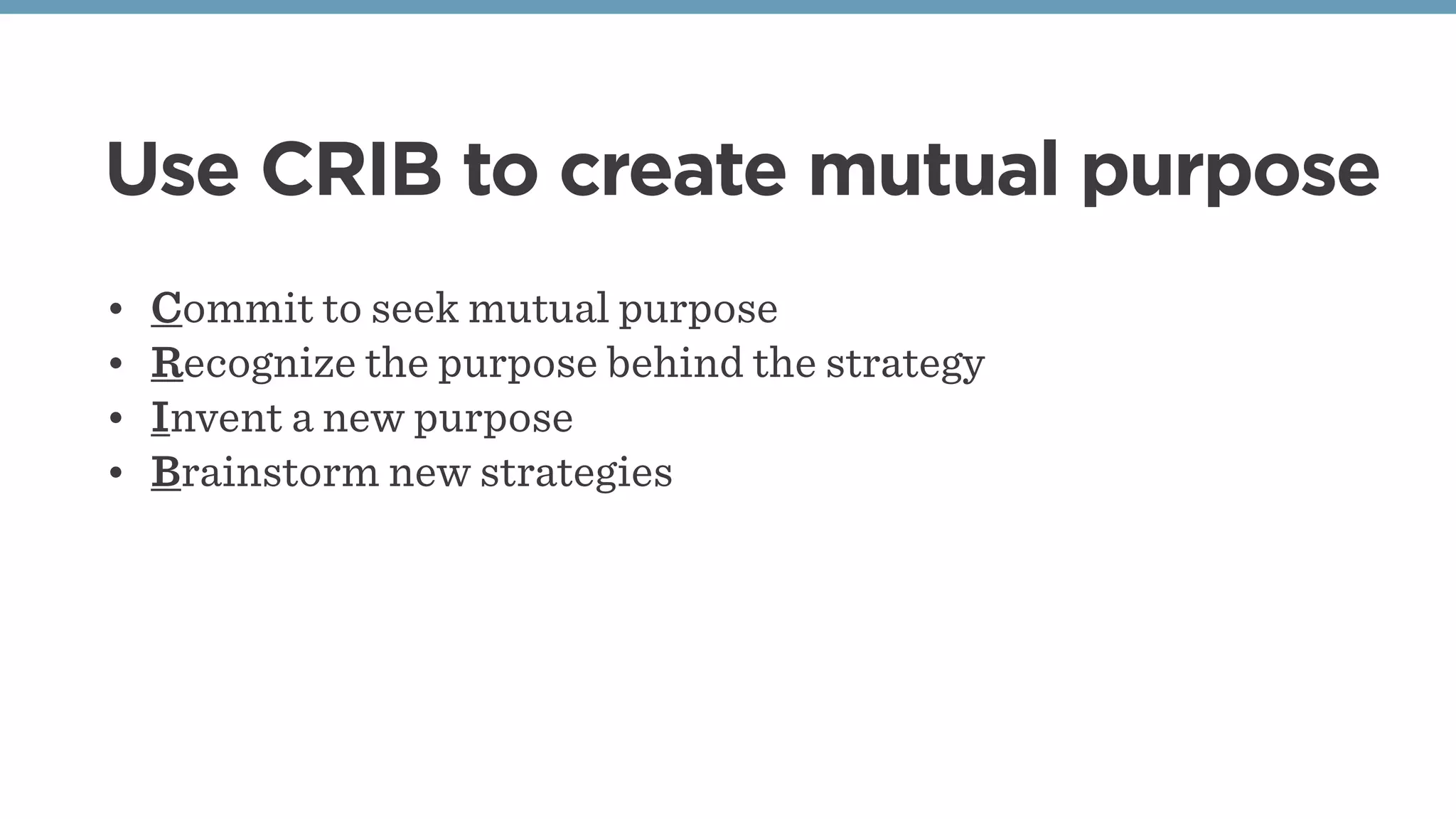

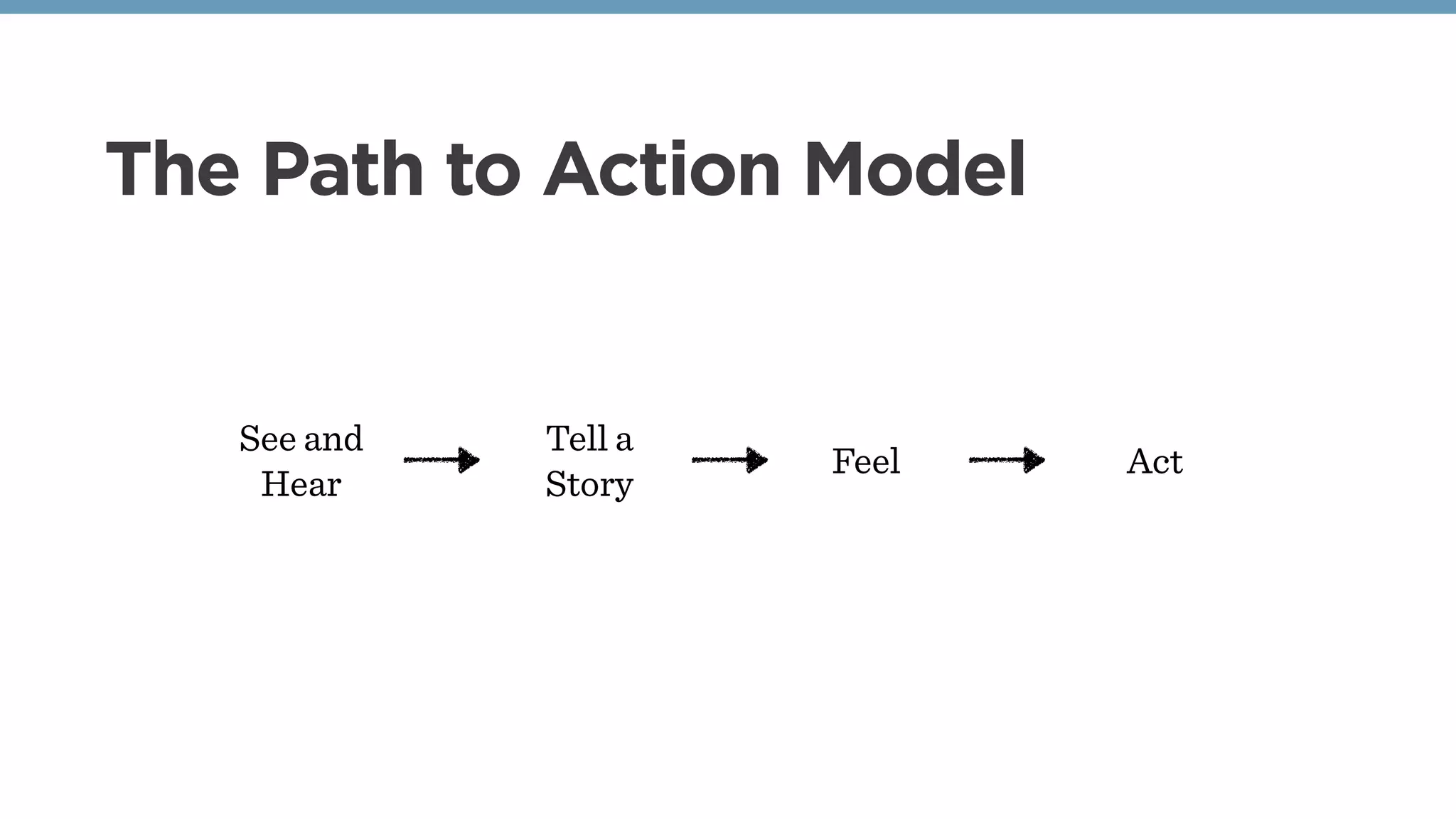

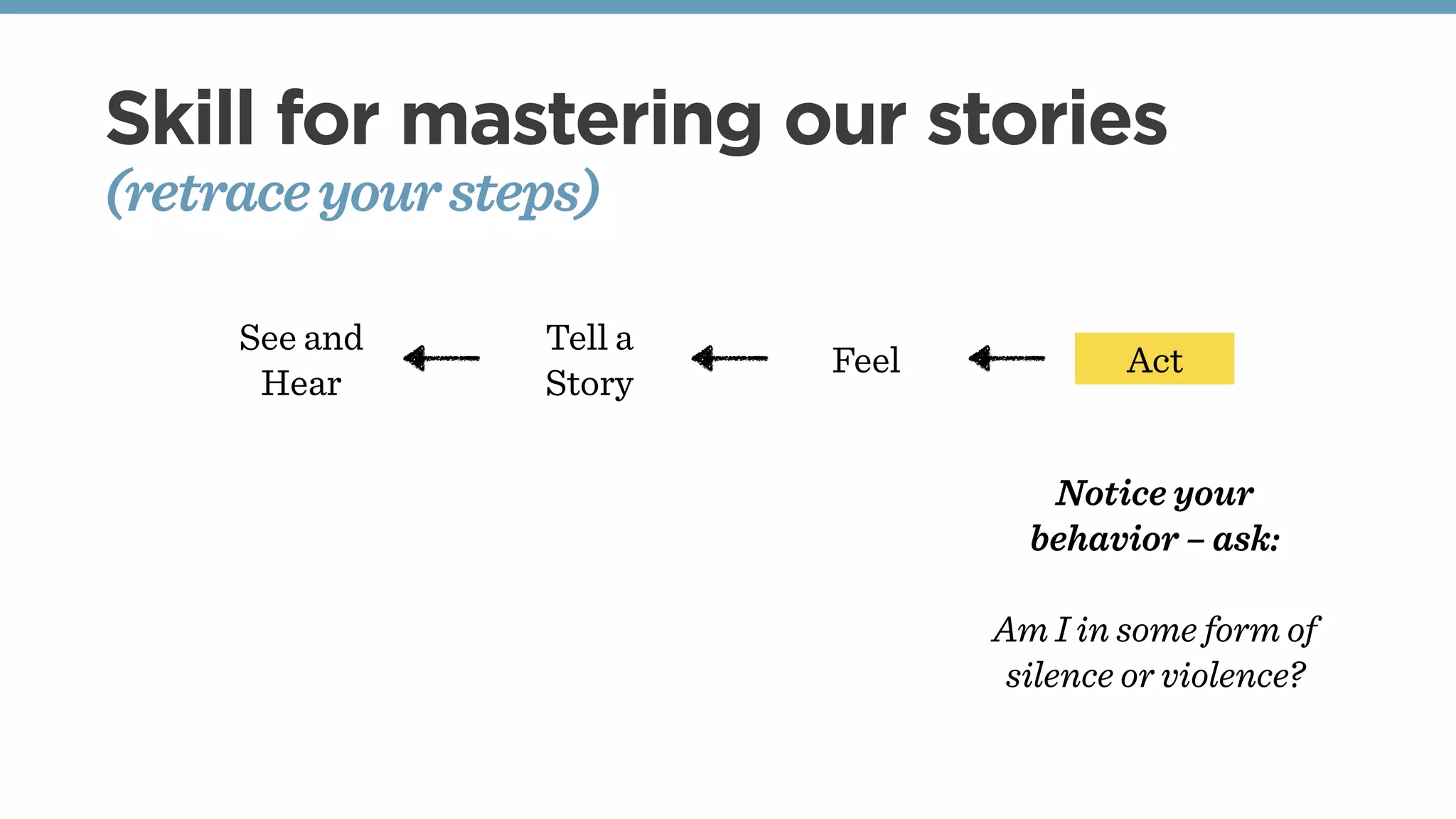

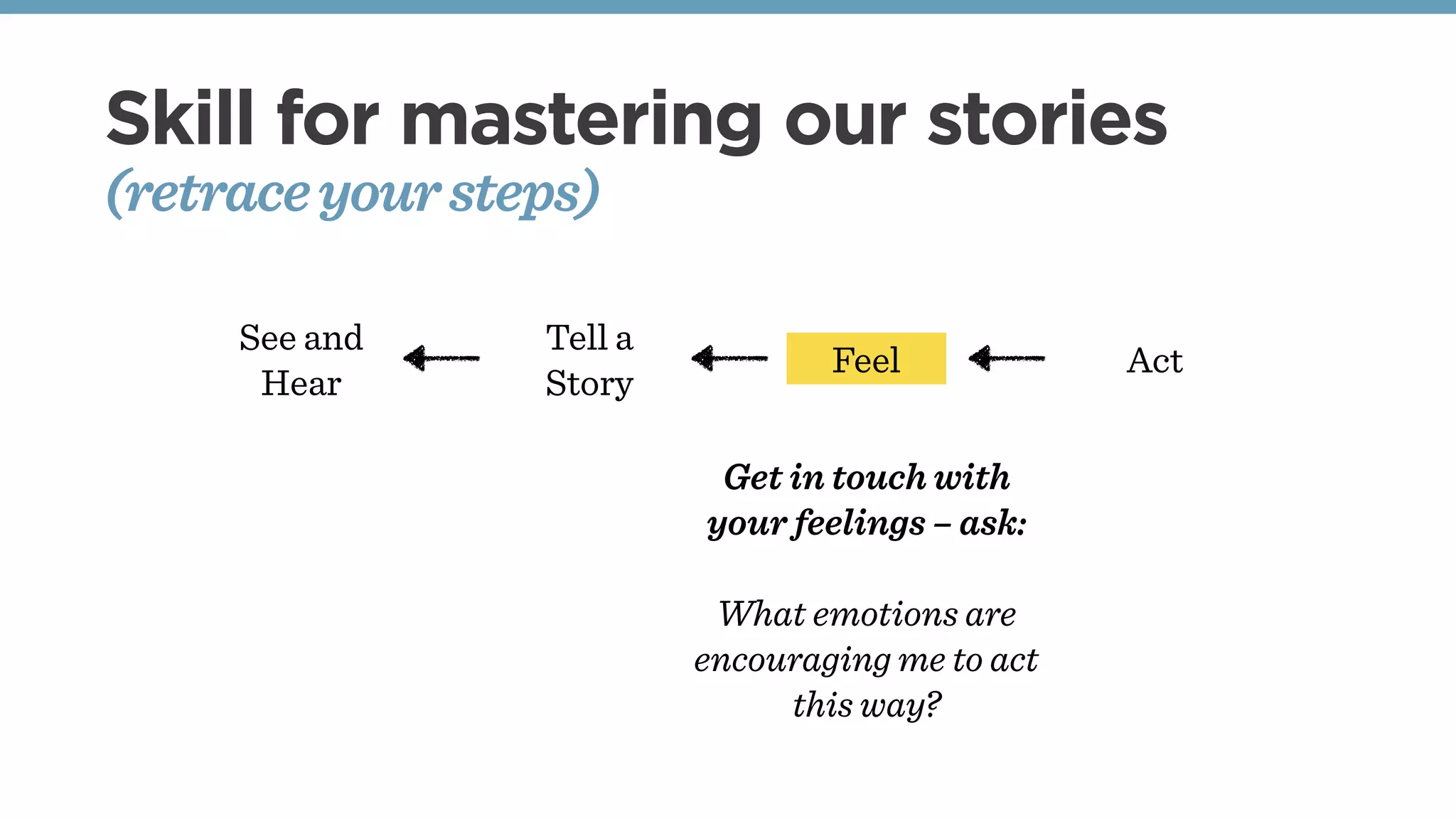

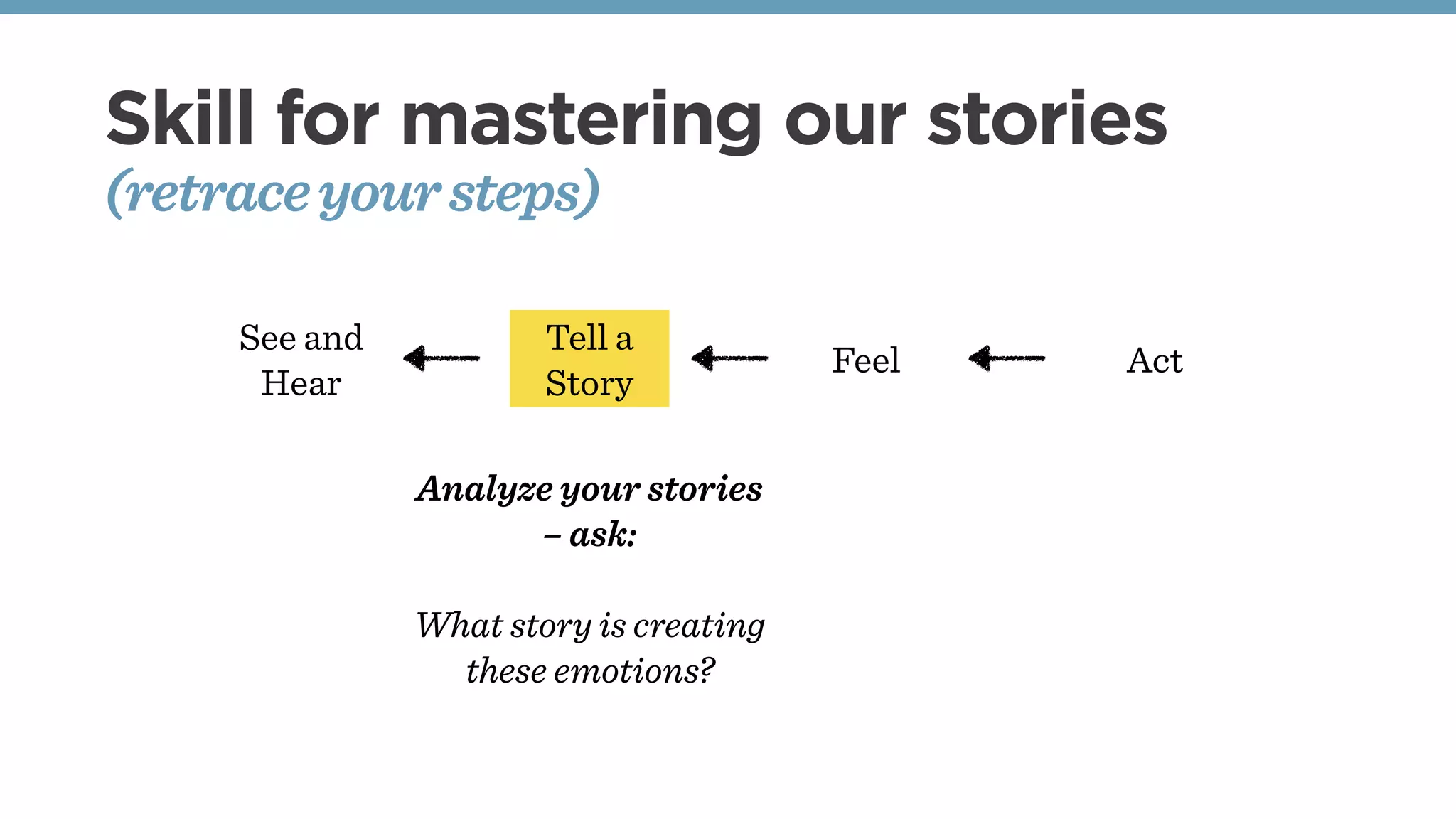

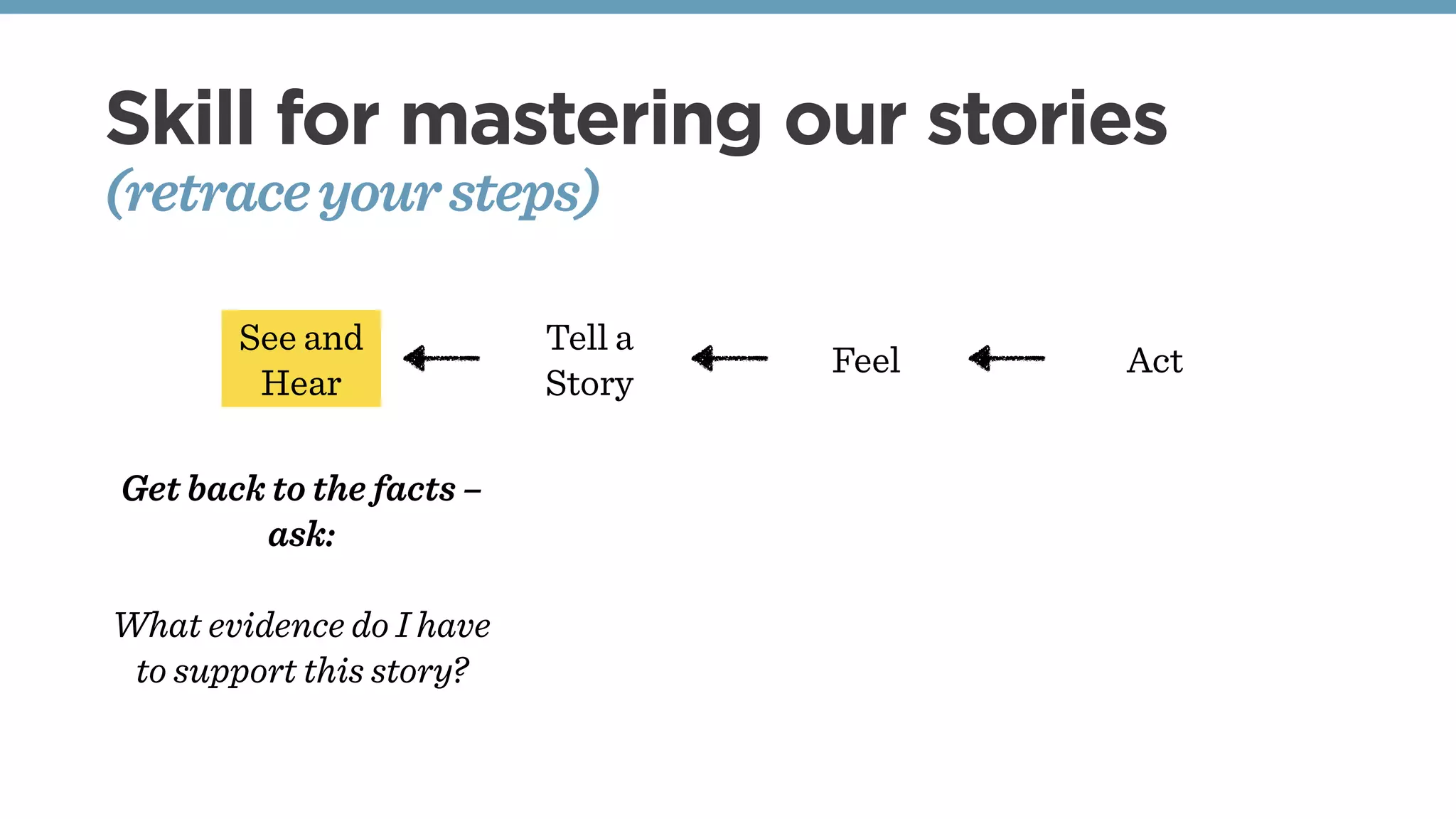

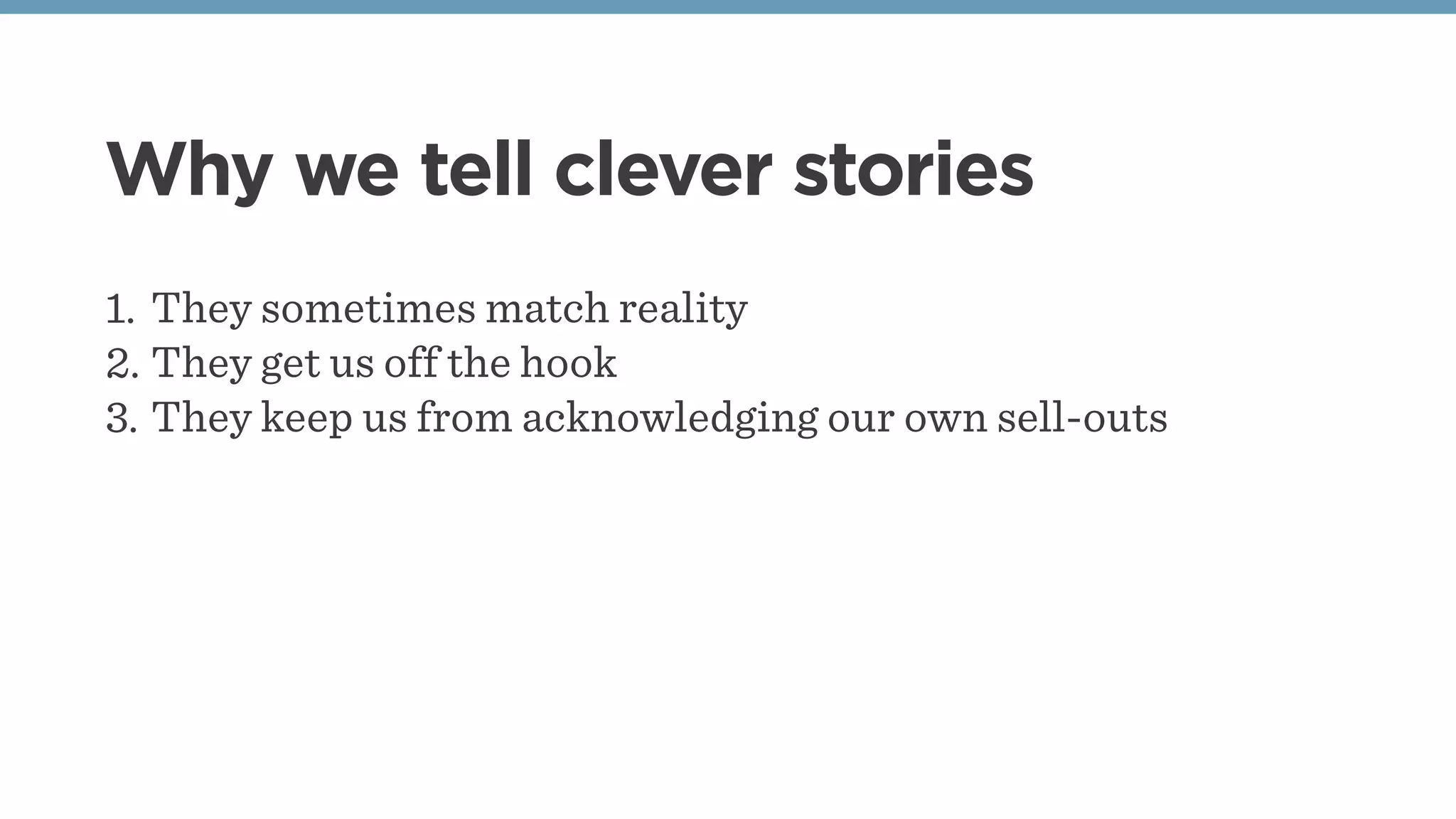

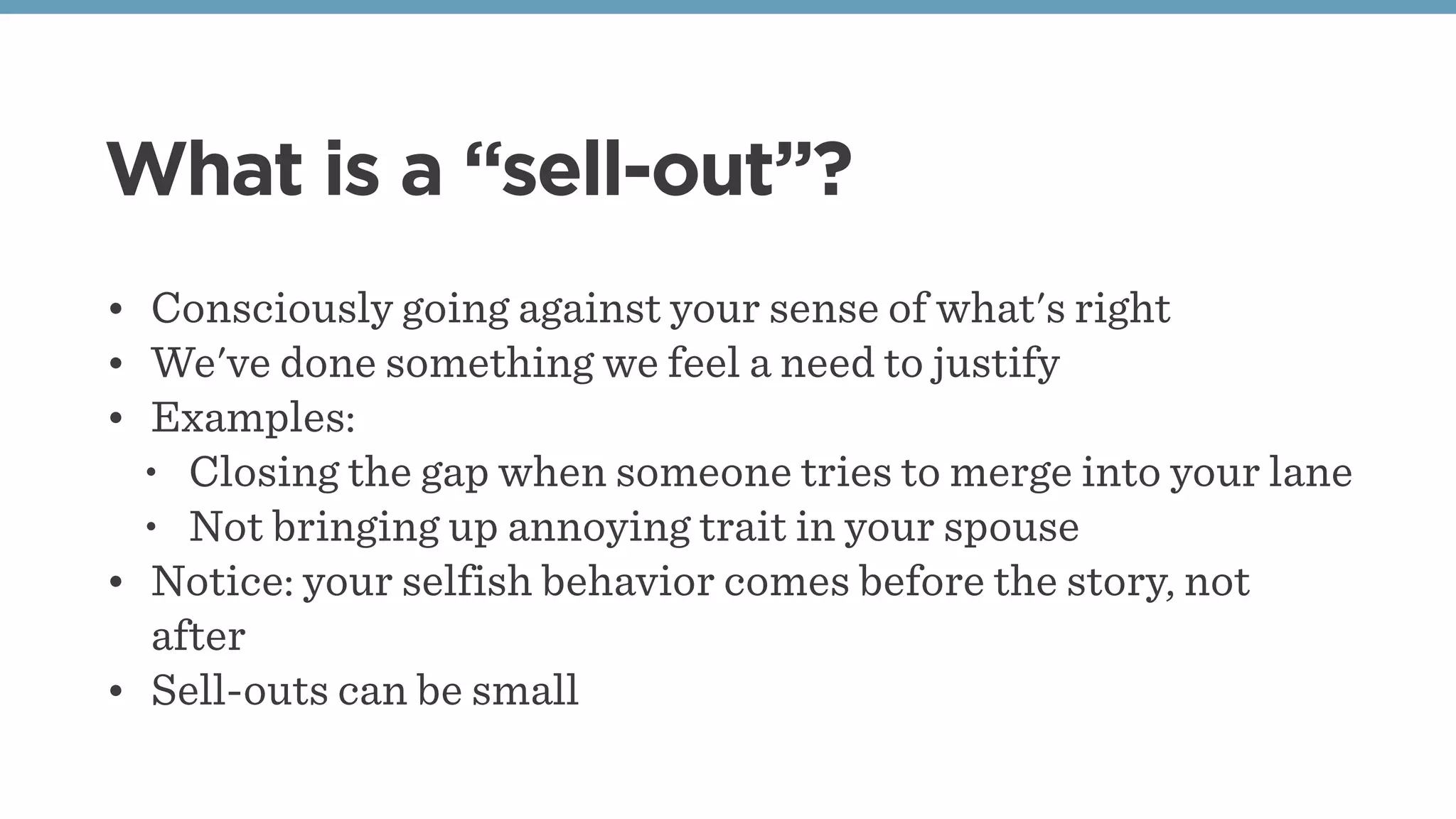

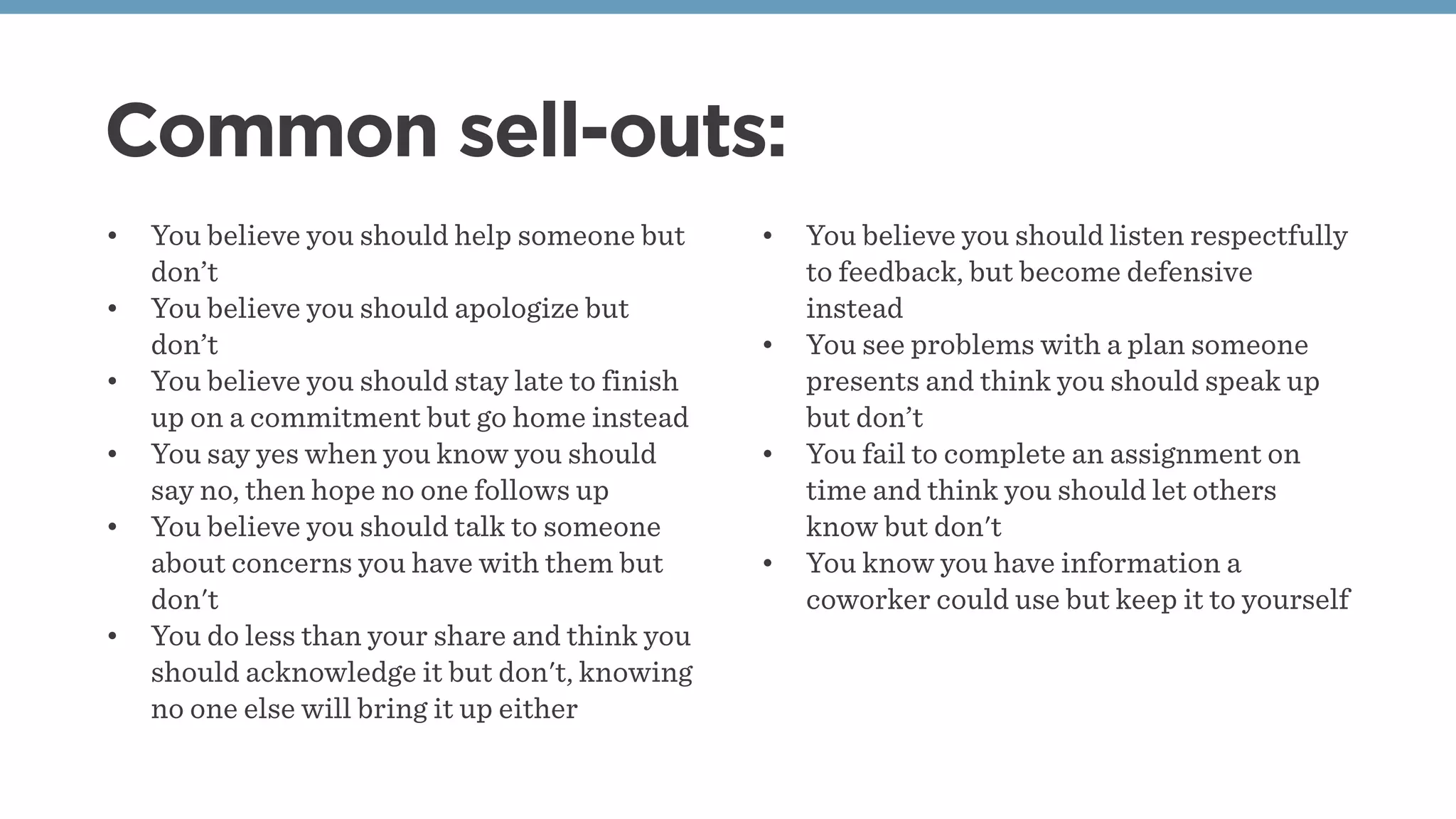

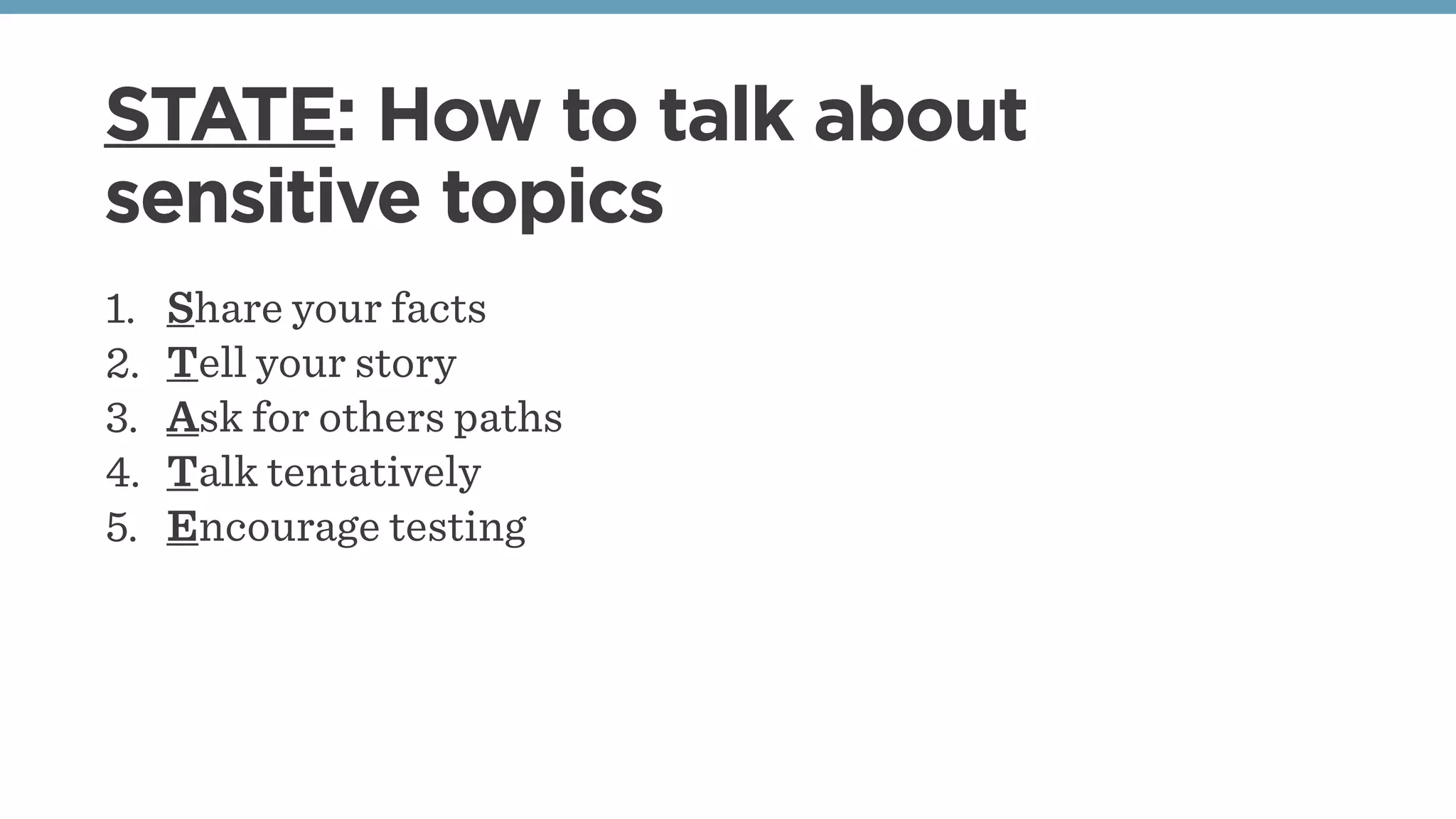

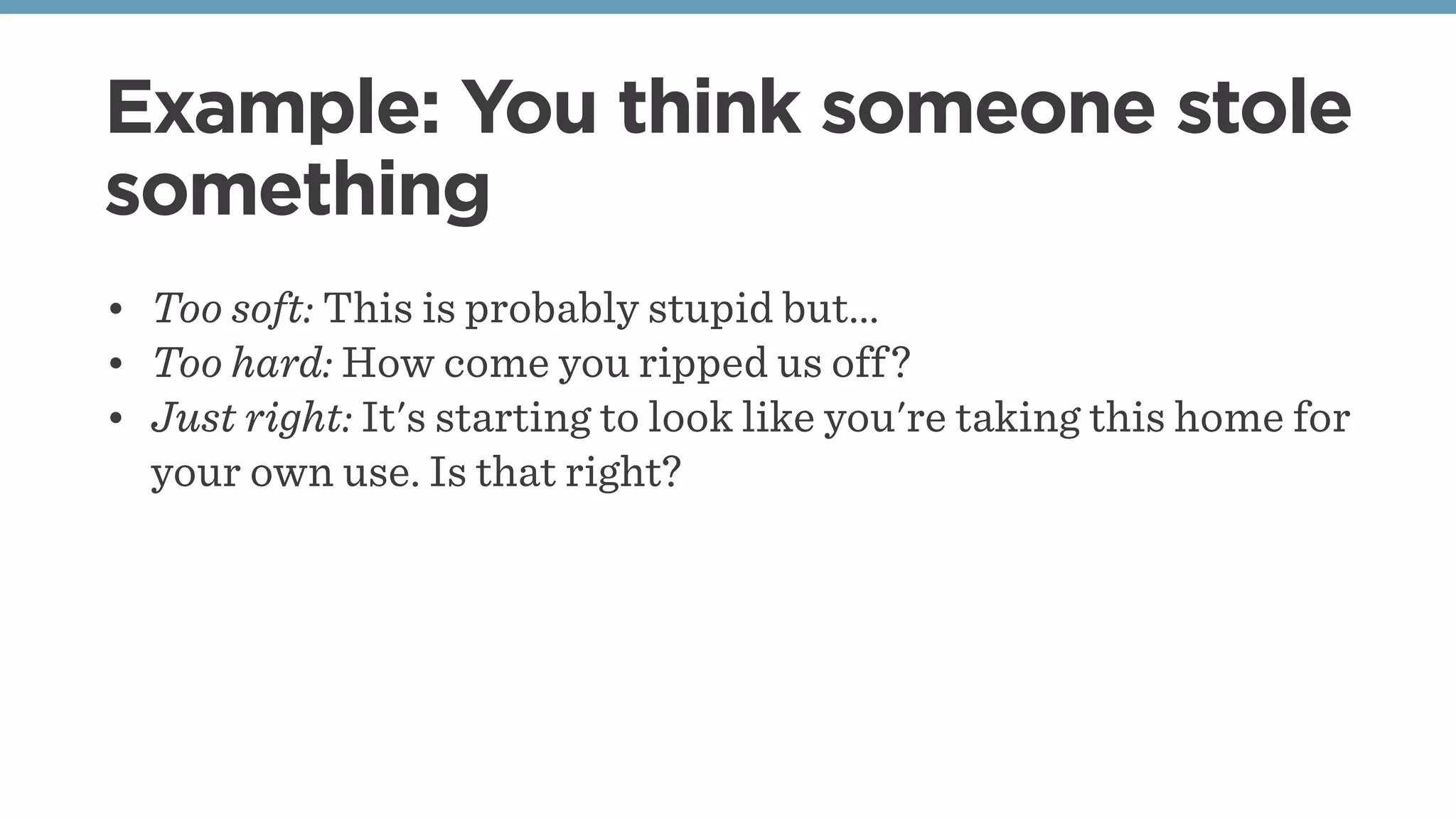

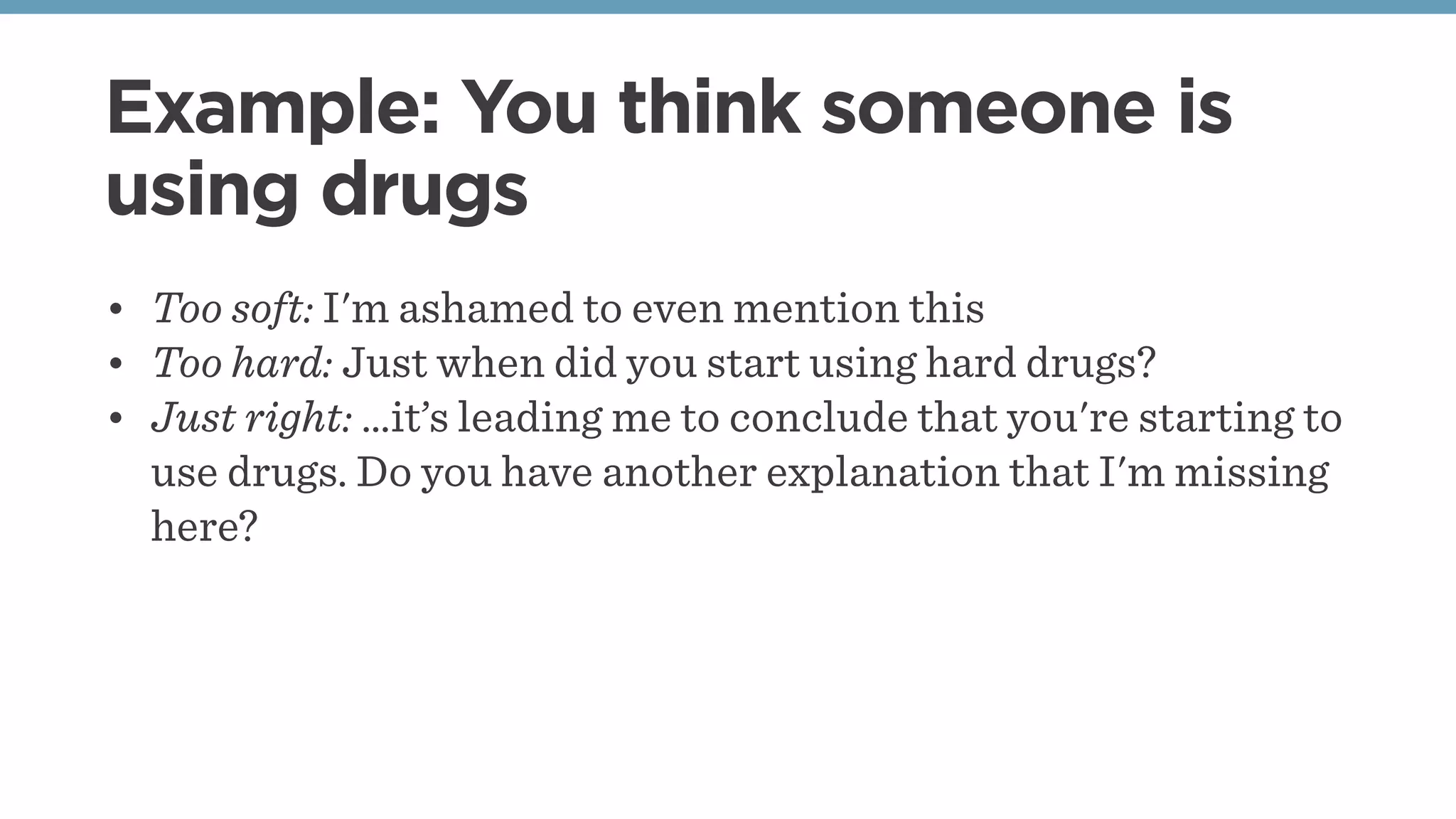

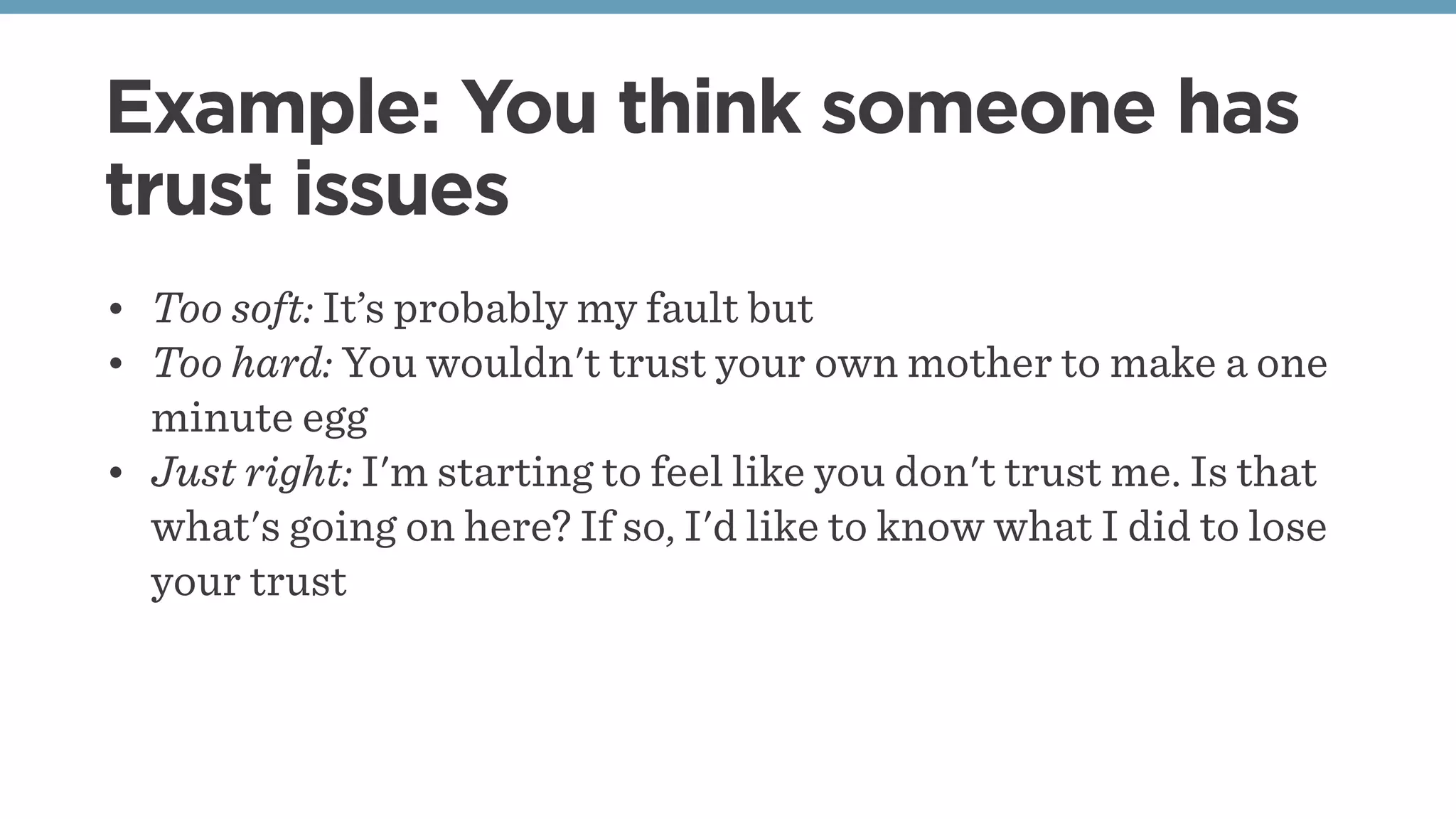

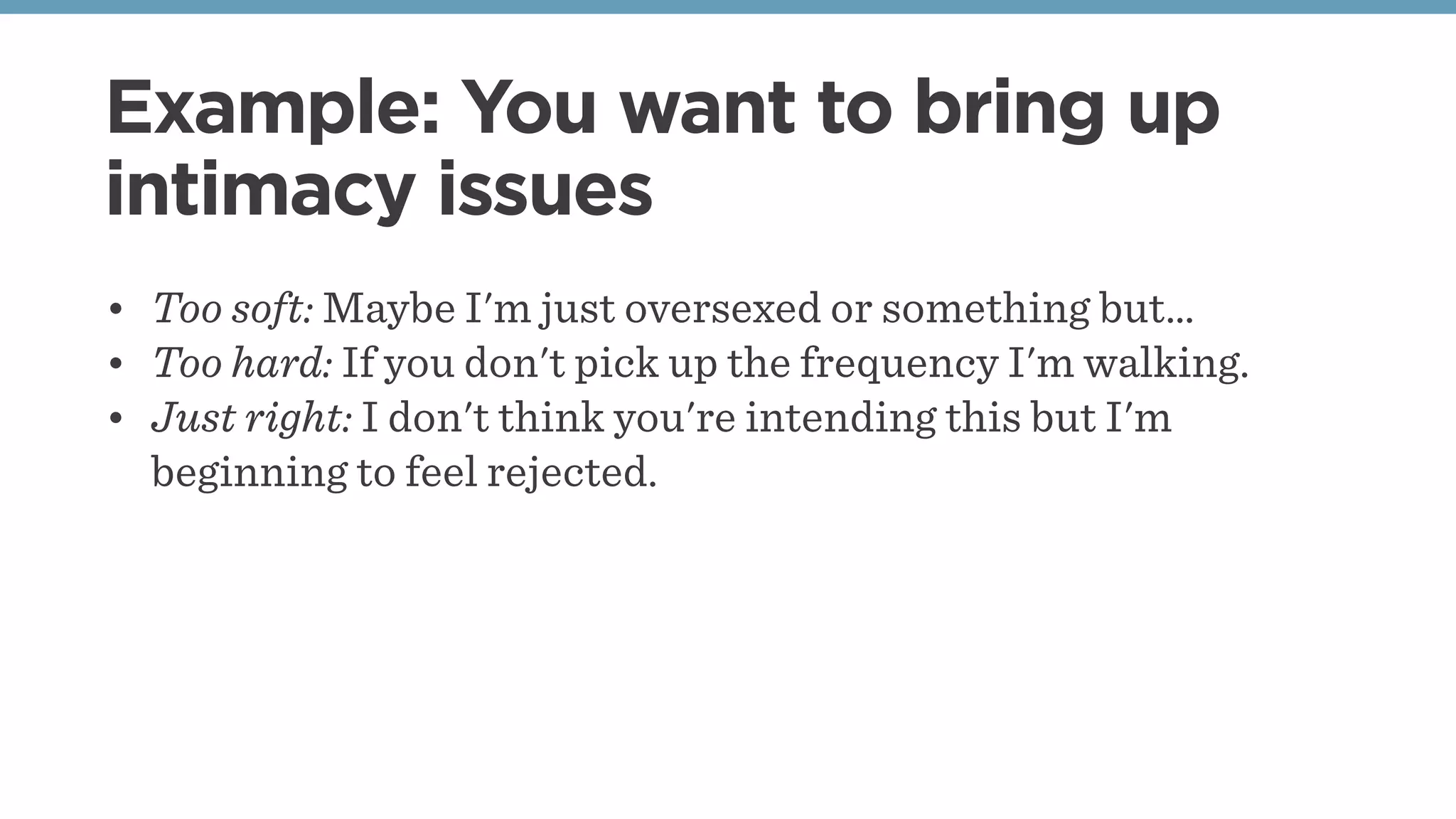

This document provides guidance on having difficult conversations by discussing how to make such conversations safe and productive. It notes that crucial conversations are discussions where stakes are high, opinions vary, and emotions run strong. Such conversations often go poorly due to factors like biology, surprise, confusion, and self-defeating behavior. The document outlines how to start with the right motives by focusing on what you and others really want, rather than protective behaviors. It also discusses how to notice when safety is at risk by looking for signs of silence or violence in conversations. Specific tactics are provided for rebuilding mutual purpose and mutual respect to make conversations safe, including apologizing, contrasting to repair misunderstandings, and using C.R.I.B. to