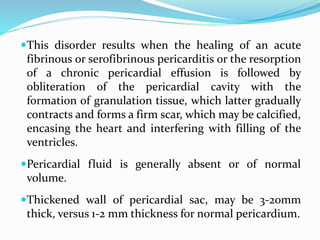

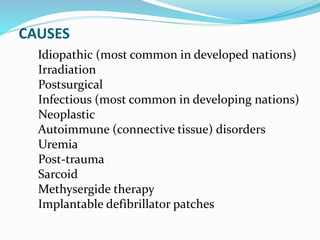

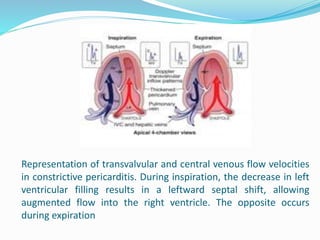

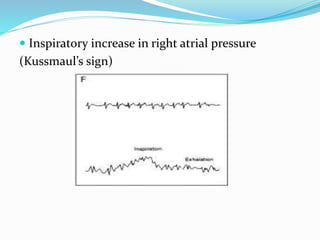

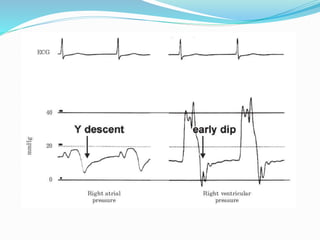

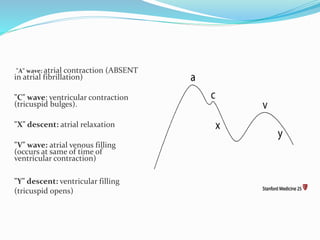

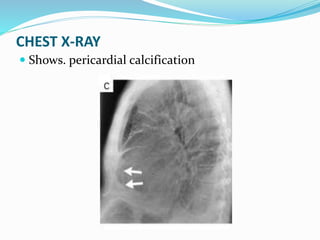

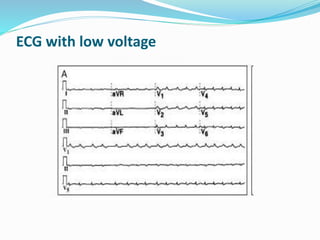

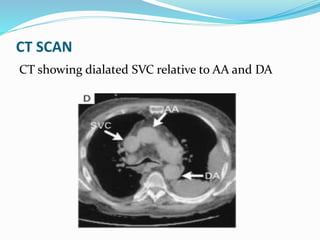

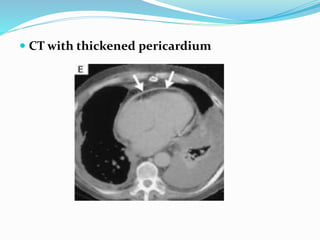

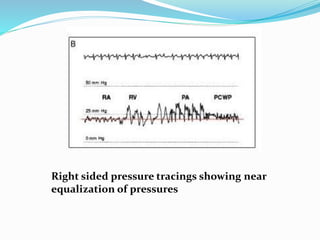

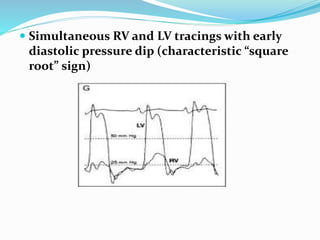

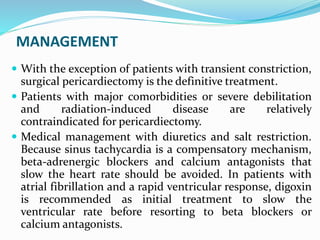

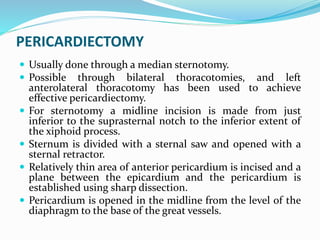

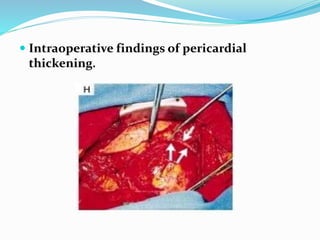

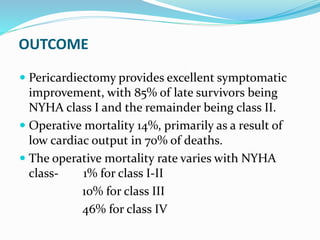

Chronic constrictive pericarditis is a condition where the pericardium thickens and scar tissue forms, restricting the heart's ability to fill with blood. It results from various causes like infections, surgery, radiation, or autoimmune disorders. On examination, elevated jugular venous pressure and equalization of cardiac filling pressures are seen. Imaging like echocardiograms and CT scans show thickened pericardium. Definitive treatment is surgical removal of the pericardium (pericardiectomy), which improves symptoms in most patients.