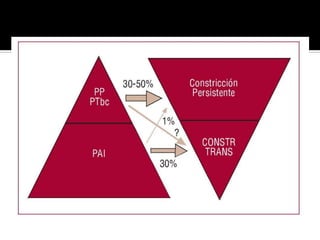

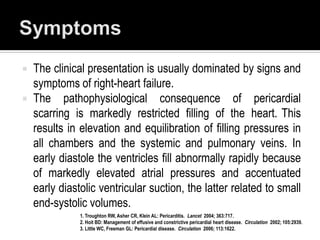

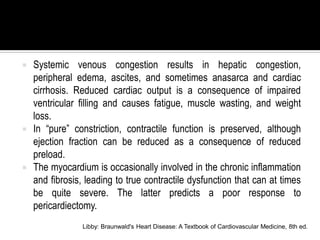

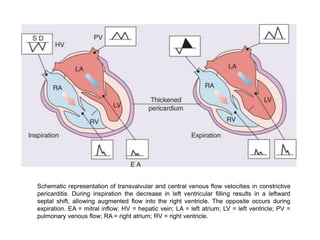

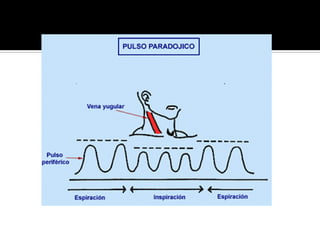

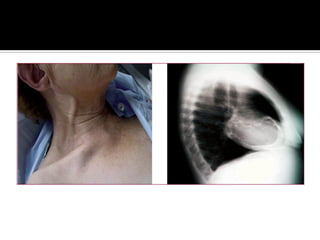

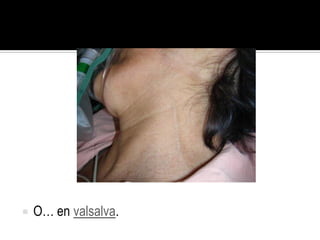

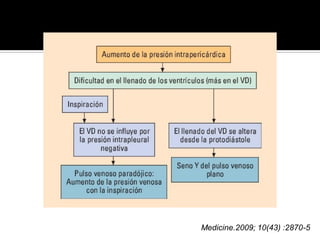

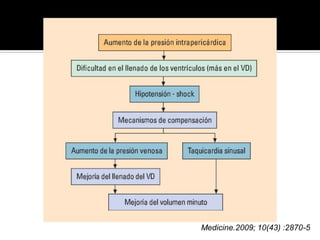

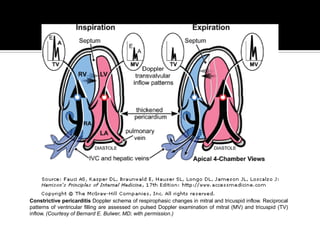

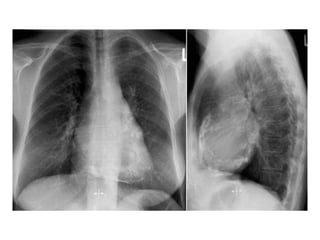

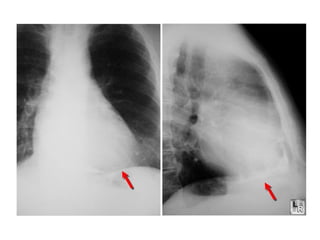

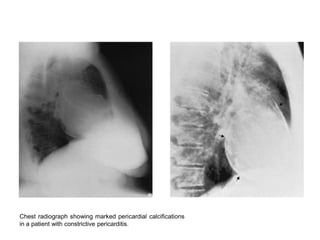

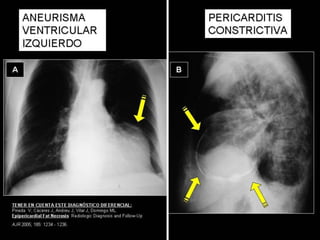

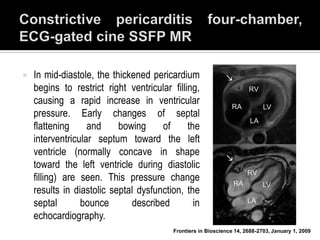

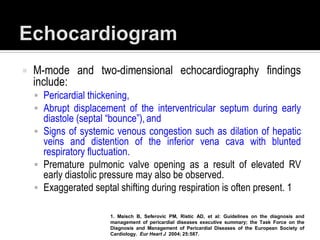

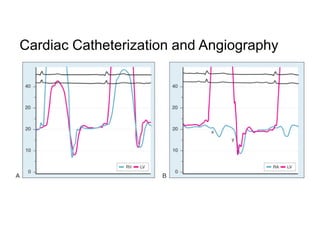

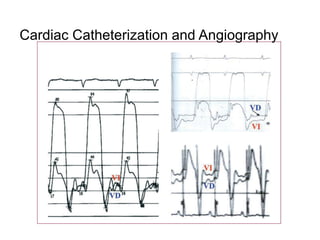

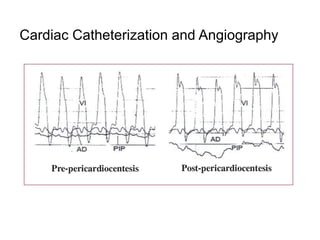

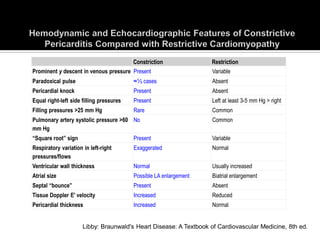

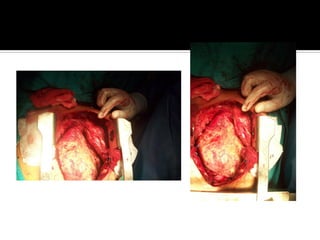

This document discusses constrictive pericarditis. It begins with definitions and mentions that constrictive pericarditis is the end stage of an inflammatory process involving the pericardium. Common causes in developed countries include idiopathic, postsurgical, or radiation injury, while tuberculosis is more common in developing countries. Over time, fibrosis and scarring of the pericardium develops, restricting heart filling. Clinical presentation involves signs of right heart failure like edema and ascites. Diagnosis involves identifying signs of restricted filling on imaging and hemodynamics. Treatment is surgical pericardiectomy except for transient cases.