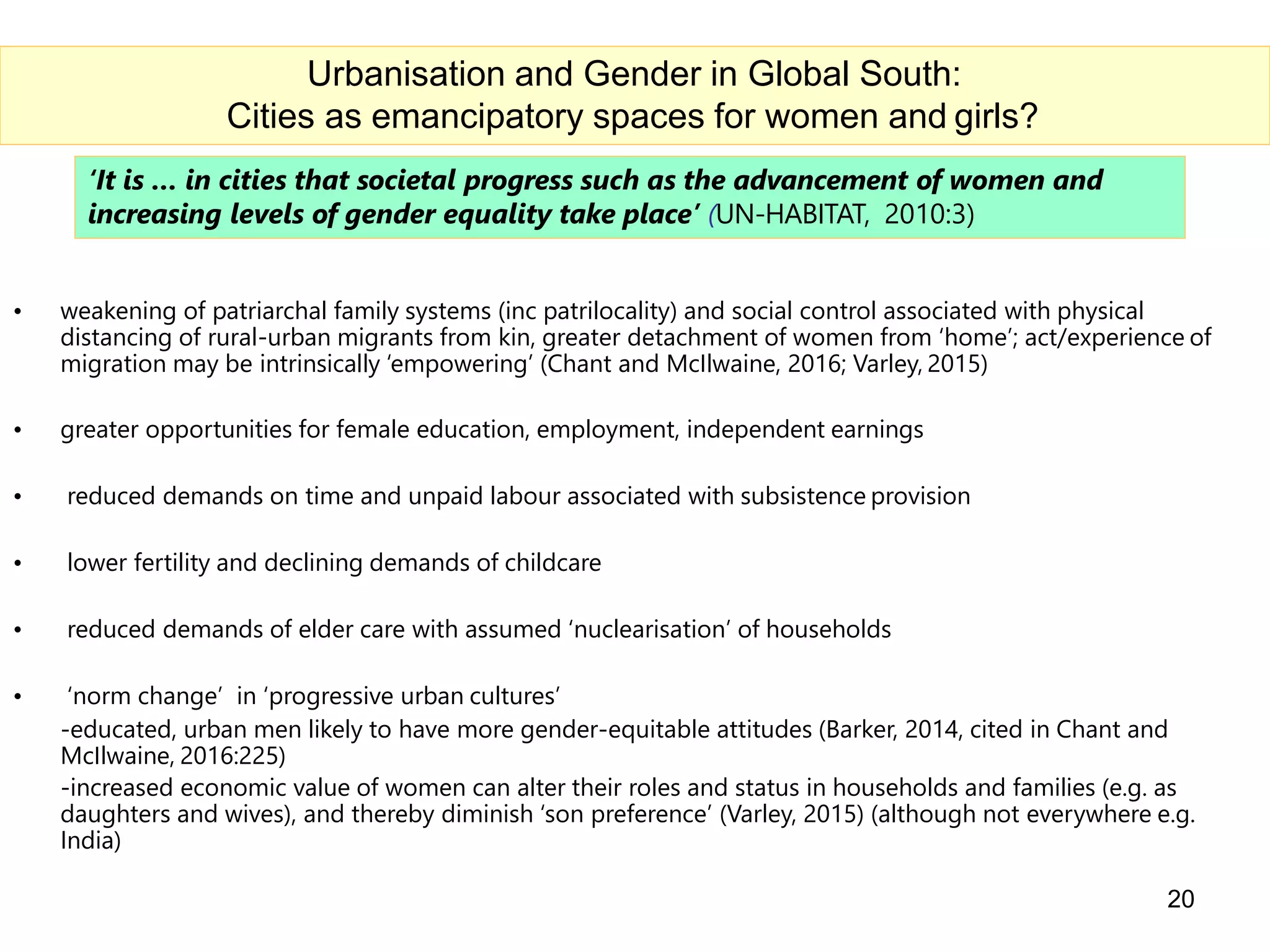

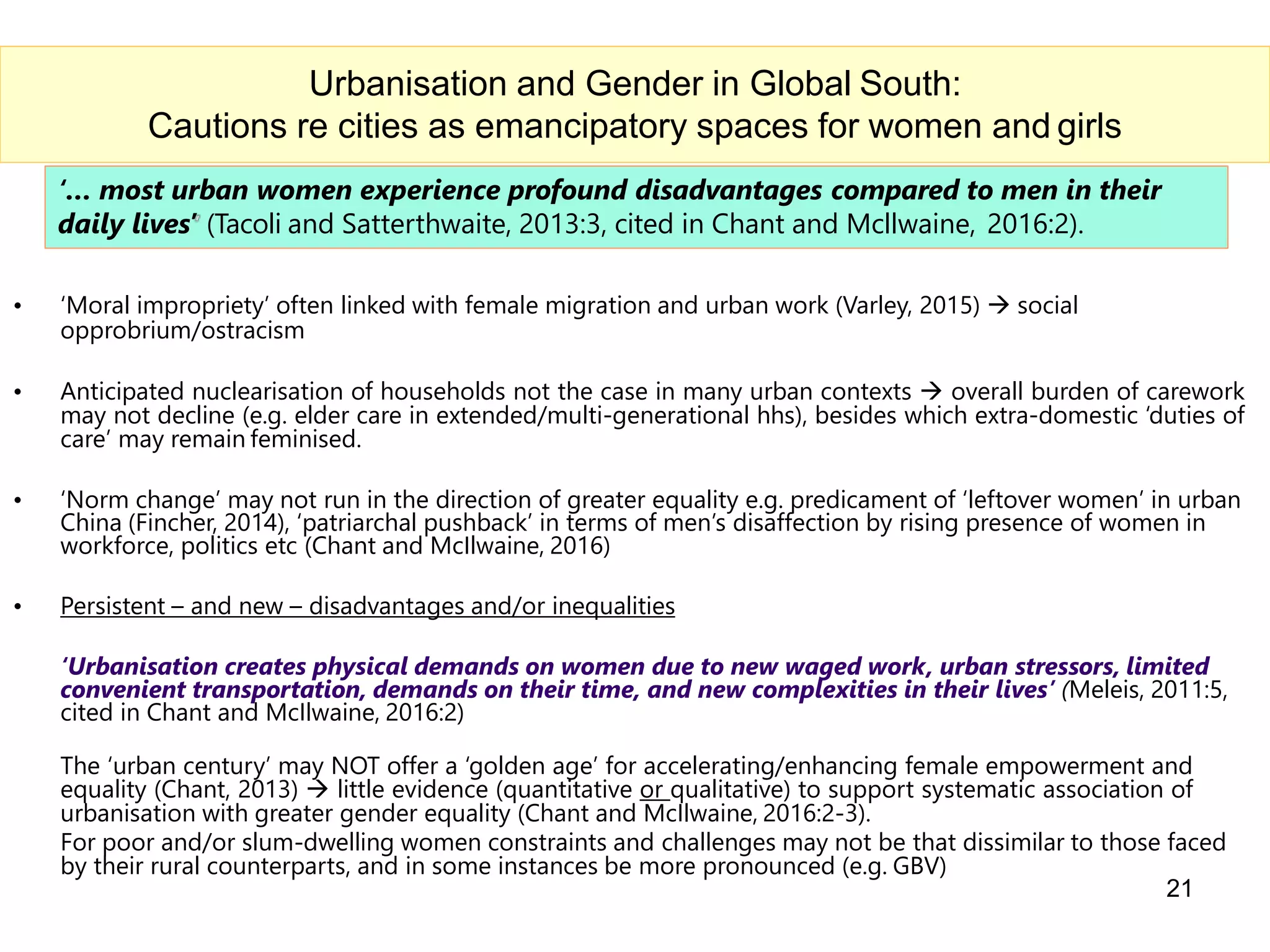

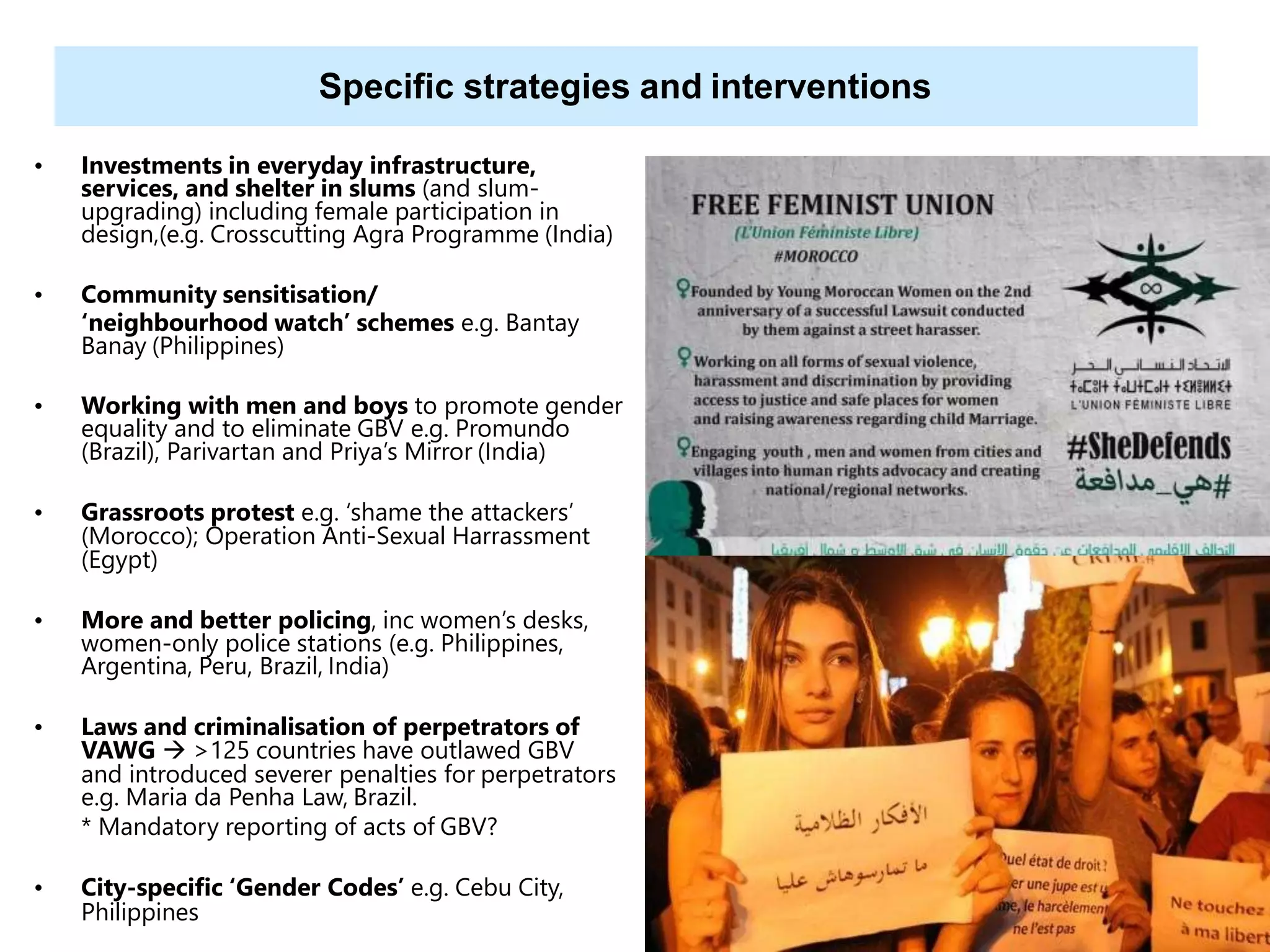

The lecture by Professor Sylvia Chant discusses the intersection of gender, urbanization, and poverty, highlighting the unique challenges faced by women and girls in slum environments of the Global South. It emphasizes the need for a gendered perspective in urban policy and planning to address pervasive inequalities, as many urbanization assumptions do not hold true for slum-dwelling women. The presentation also explores the role of women in household and community dynamics, noting that urbanization can lead to both opportunities and constraints for gender equality.

![Echoes and further thoughts on making future cities gender-fair,

‘empowering’ for women and girls … and ‘feminist’

• More collection and dissemination of spatially-disaggregated (e.g. slum/non-slum) as well as

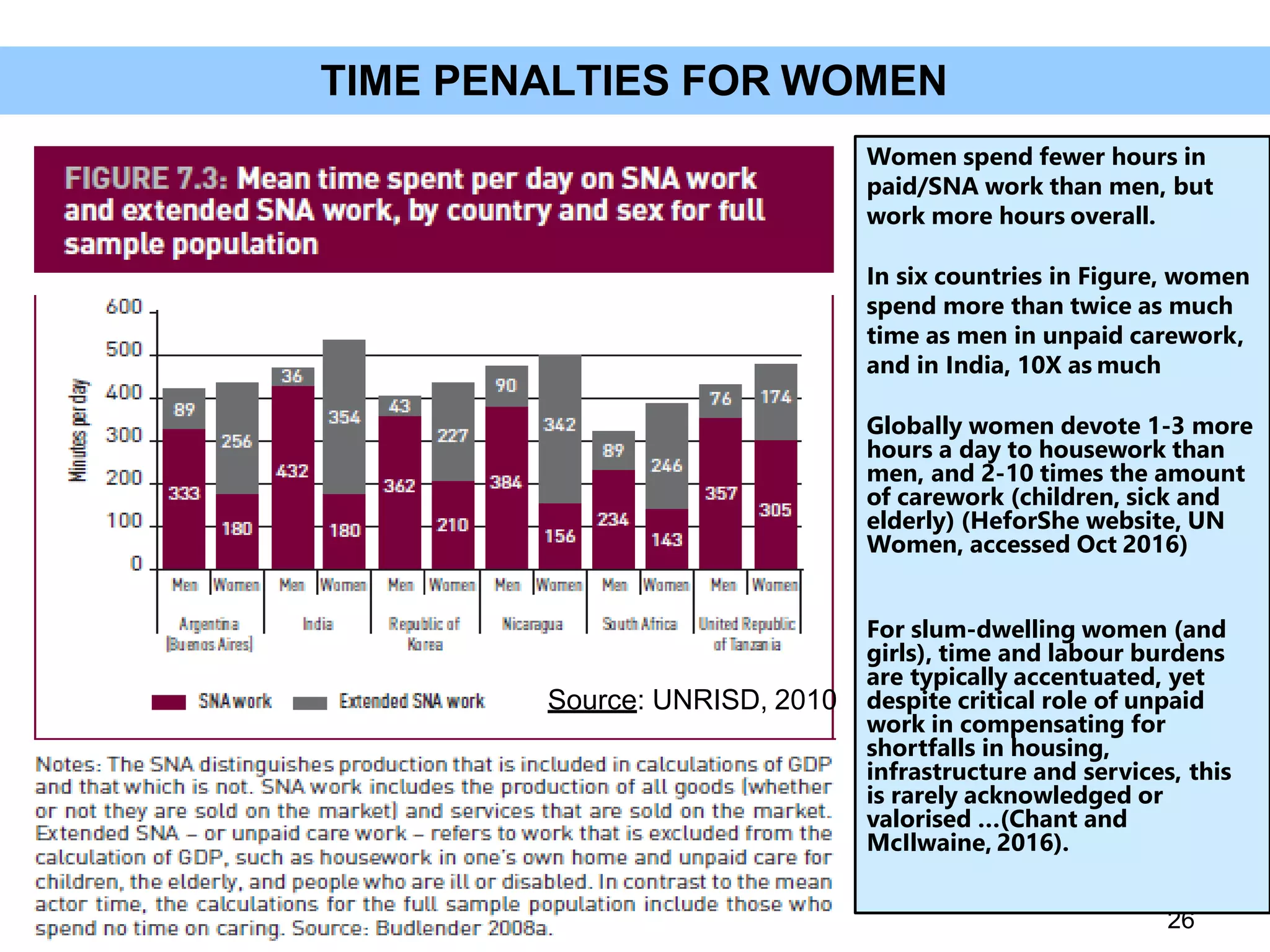

sex-disaggregated data (e.g. on time-use)?

‘What gets counted is more likely to get addressed’ (Moser [Annalise], 2007:7, cited in Chant and

McIlwaine, 2016)

• Greater recognition, assessment and valorisation of ‘unpaid economy’ and ‘care economy’

More attention to gender-differentiated responsibilities for unpaid labour and care

• Strategies required to address social relations between women and men which underpin

gendered divisions of labour – SDG 5, ‘50/50 by 2030’?

Work with men and boys to incentivise more equitable responsibilities for unpaid work, as well

as other household obligations such as control of income and consumption

• More attention to intersectionality – e.g. LGBT rights absent in NUA

• Move from ‘gender mainstreaming’ to ‘gender transformation’ (Moser,2016)

• Ensure that calls for ‘women’s empowerment’ and gender equality are not subordinated to

efficiency objectives -- poverty alleviation and economic growth are likely corollaries of more

gender-equitable cities but they should be treated as positive outcomes rather than the goals

that drive the gender agenda.

40](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/0803chantmanchestergdilecture-170309155630/75/Gender-Urbanisation-and-Poverty-Principles-Practice-and-the-Space-of-Slums-Professor-Sylvia-Chant-41-2048.jpg)