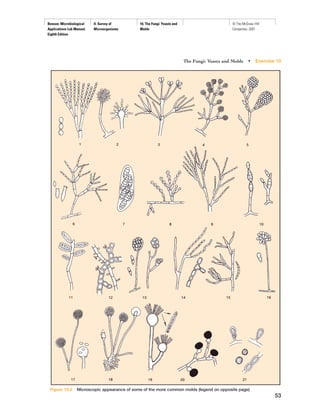

This document provides information about fungi, including yeasts and molds. It discusses the characteristics of fungi as a group, including that they are eukaryotic and nonphotosynthetic. It describes the divisions within the fungi, including the Amastigomycota division that contains yeasts and molds. The key differences between molds and yeasts are outlined, such as molds having hyphae and various types of spores while yeasts reproduce by budding. The document provides details on laboratory procedures for examining yeast and mold specimens under the microscope and identifying different mold genera.