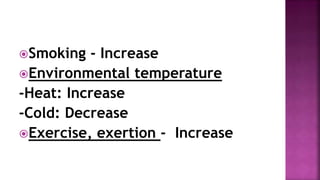

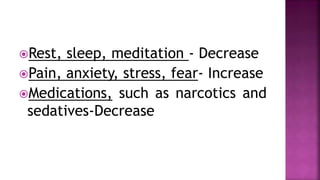

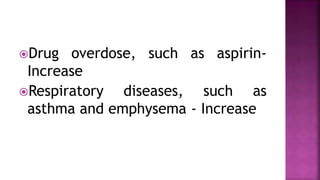

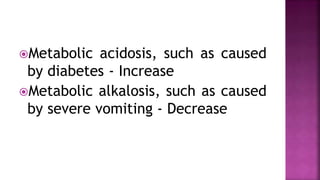

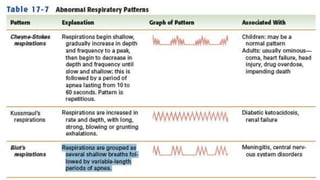

This document discusses respiration and the process of breathing. It defines respiration as the exchange of oxygen and carbon dioxide between the lungs and blood, and between blood and tissues. It describes the mechanics of breathing including inhalation driven by contraction of the diaphragm and intercostal muscles, and exhalation via relaxation of these muscles and elastic recoil of the lungs. Factors that can affect respiratory rate such as temperature, medications, and disease states are also summarized.