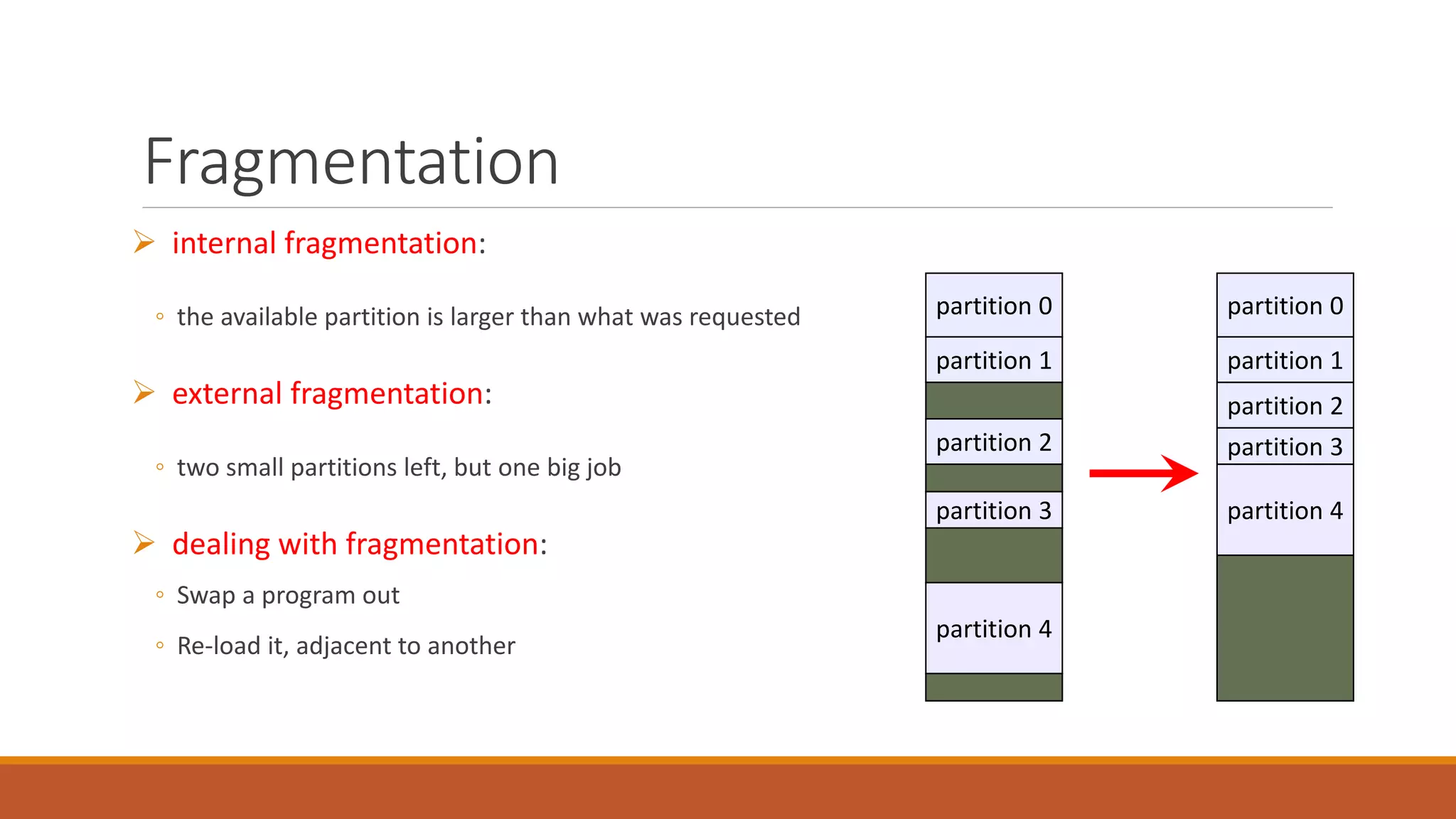

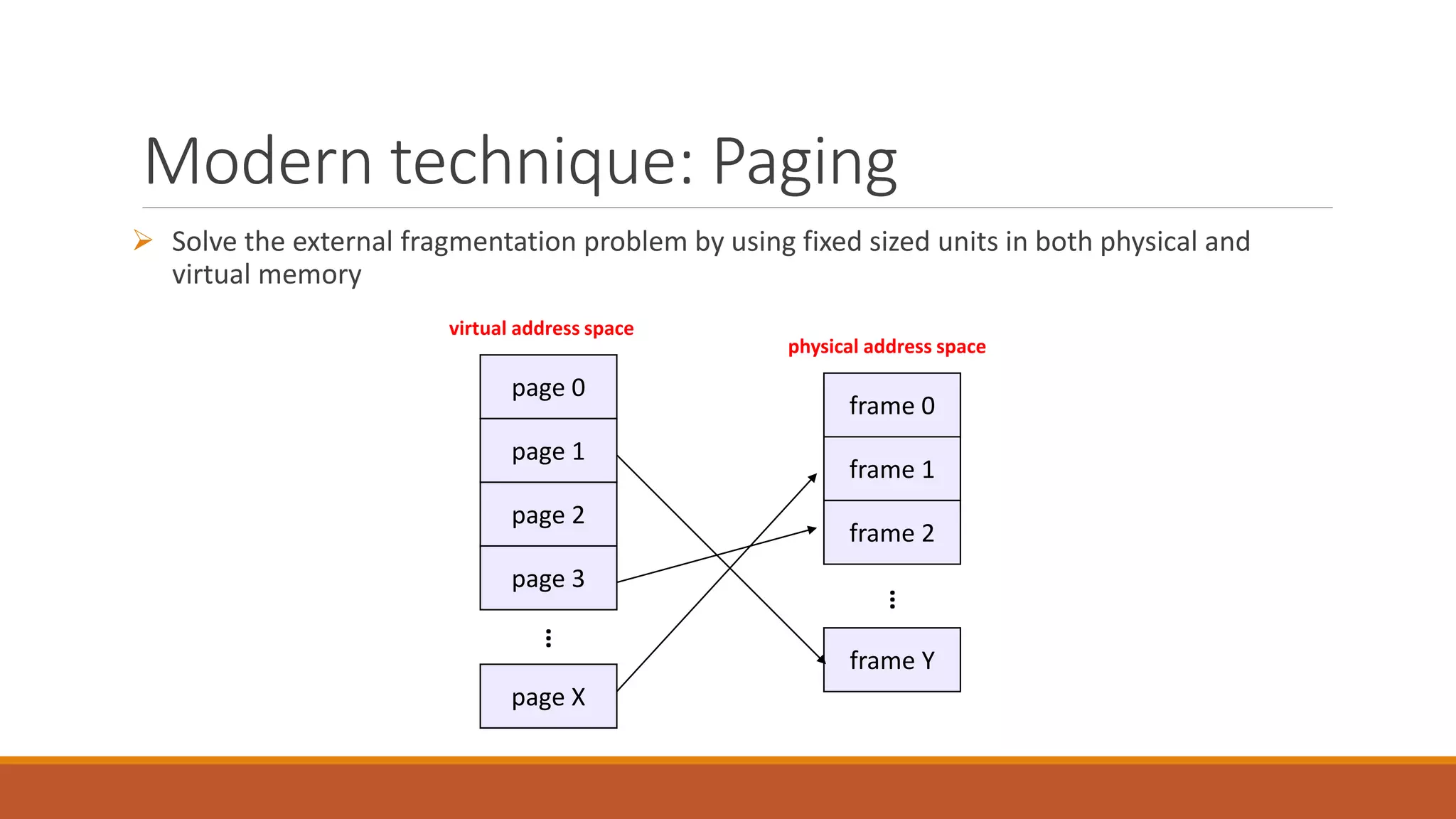

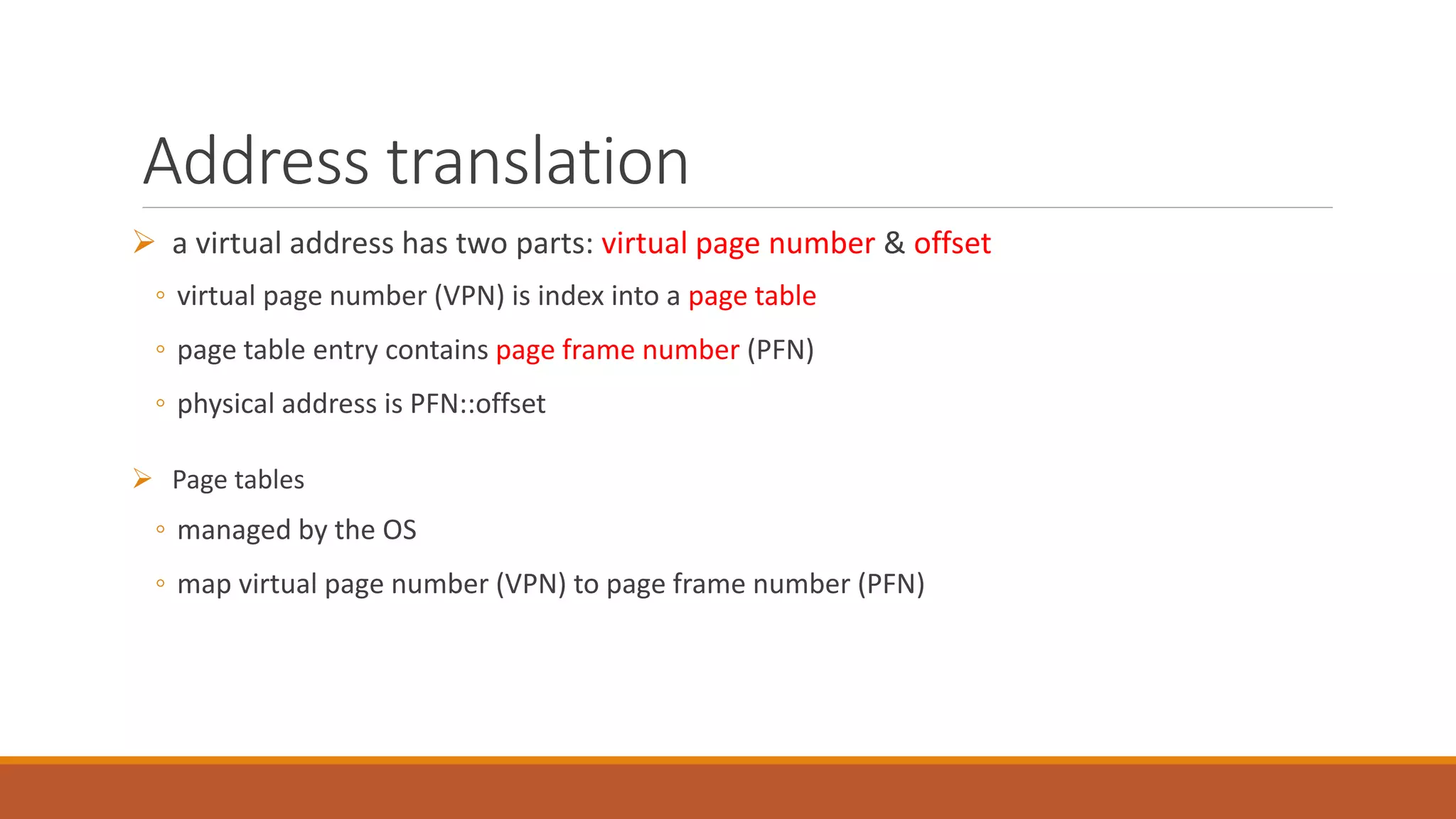

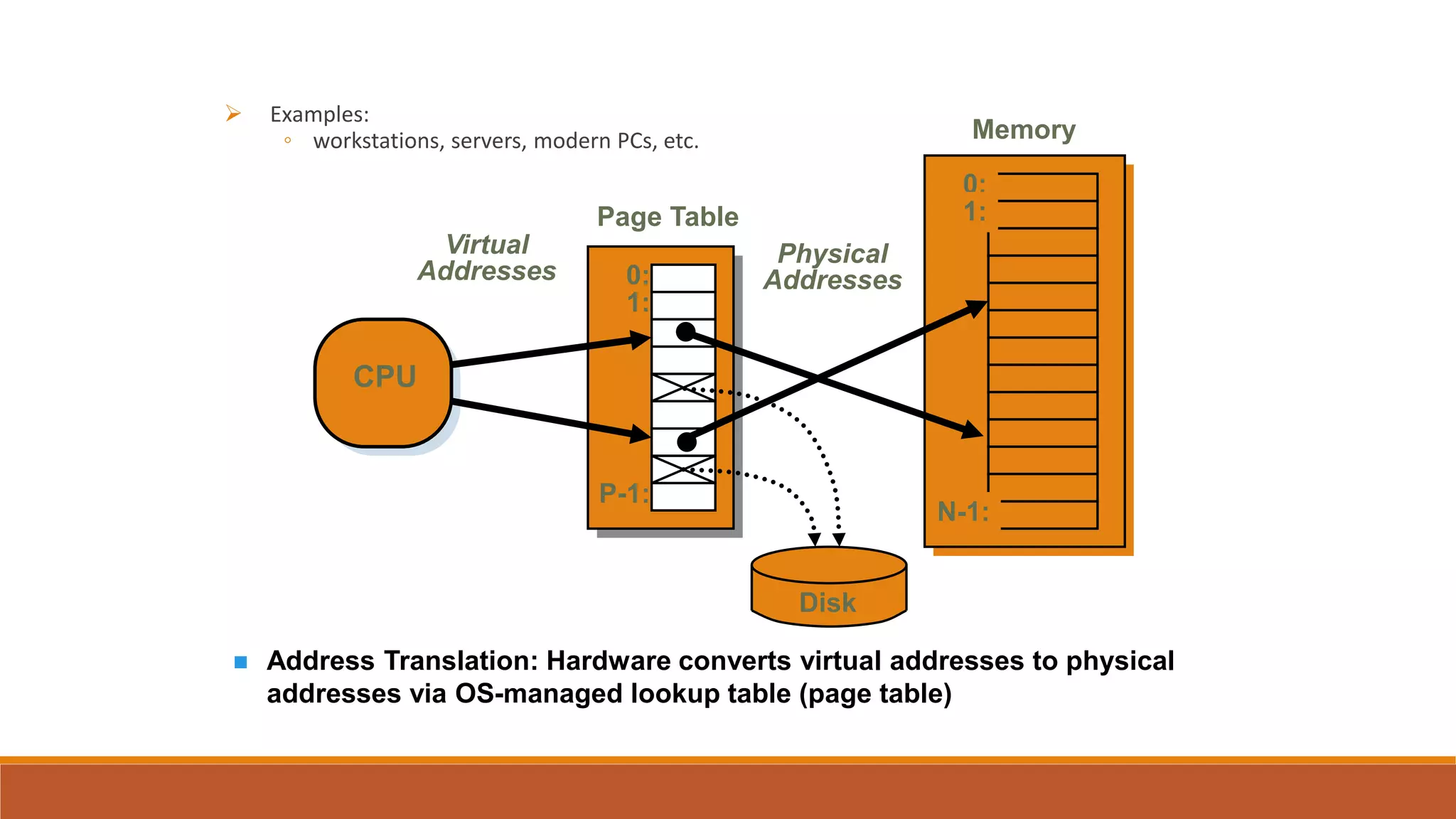

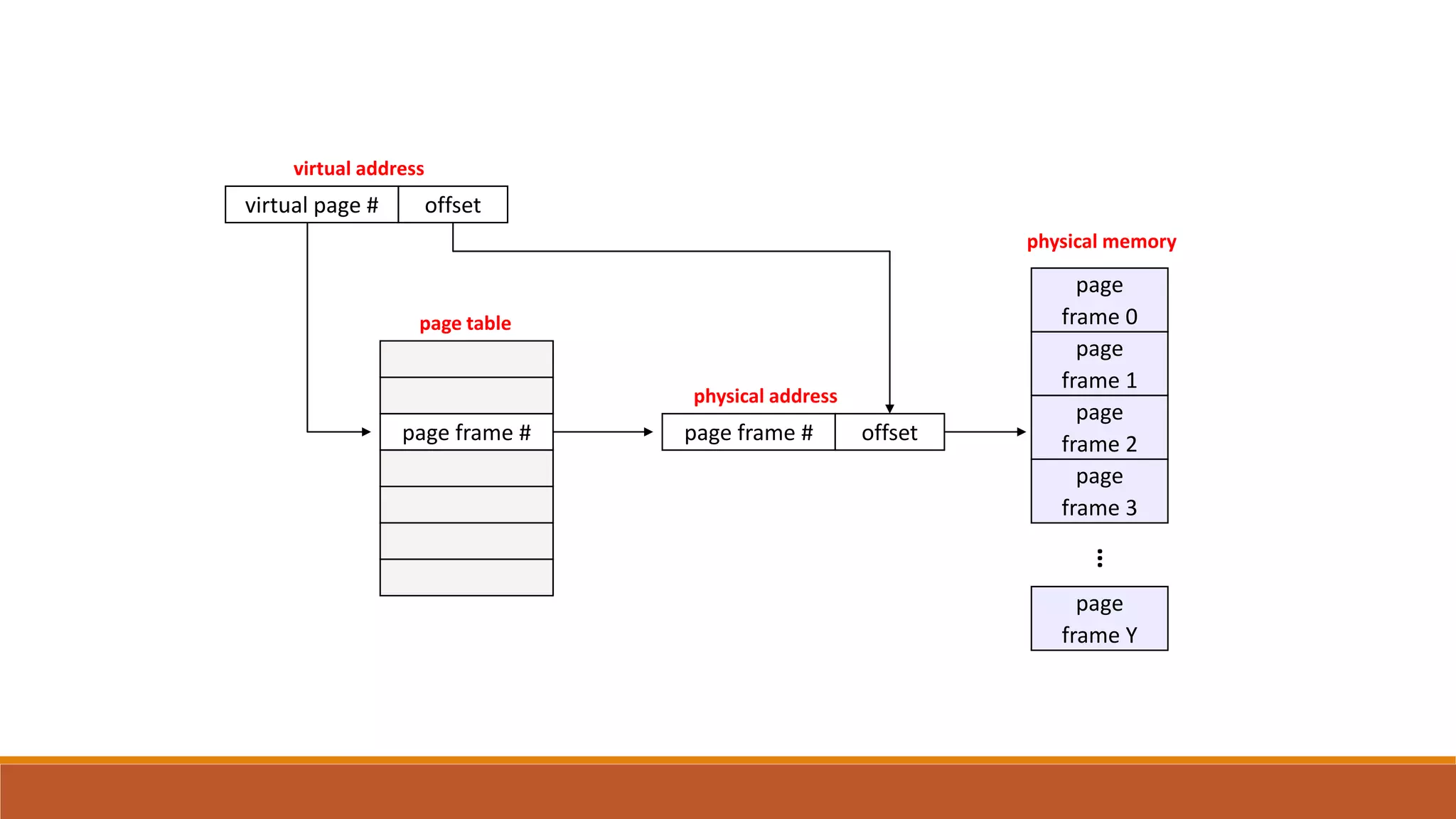

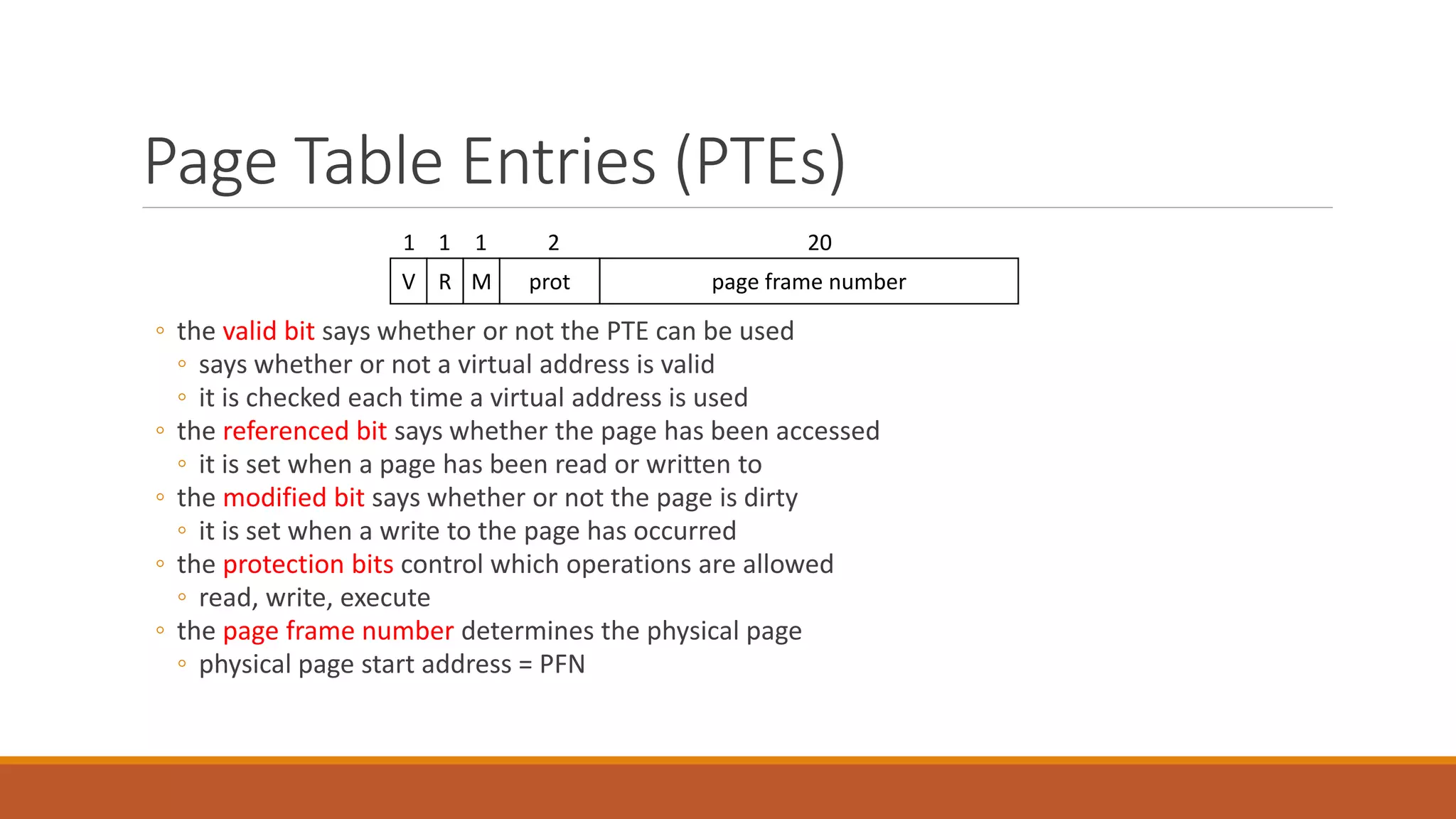

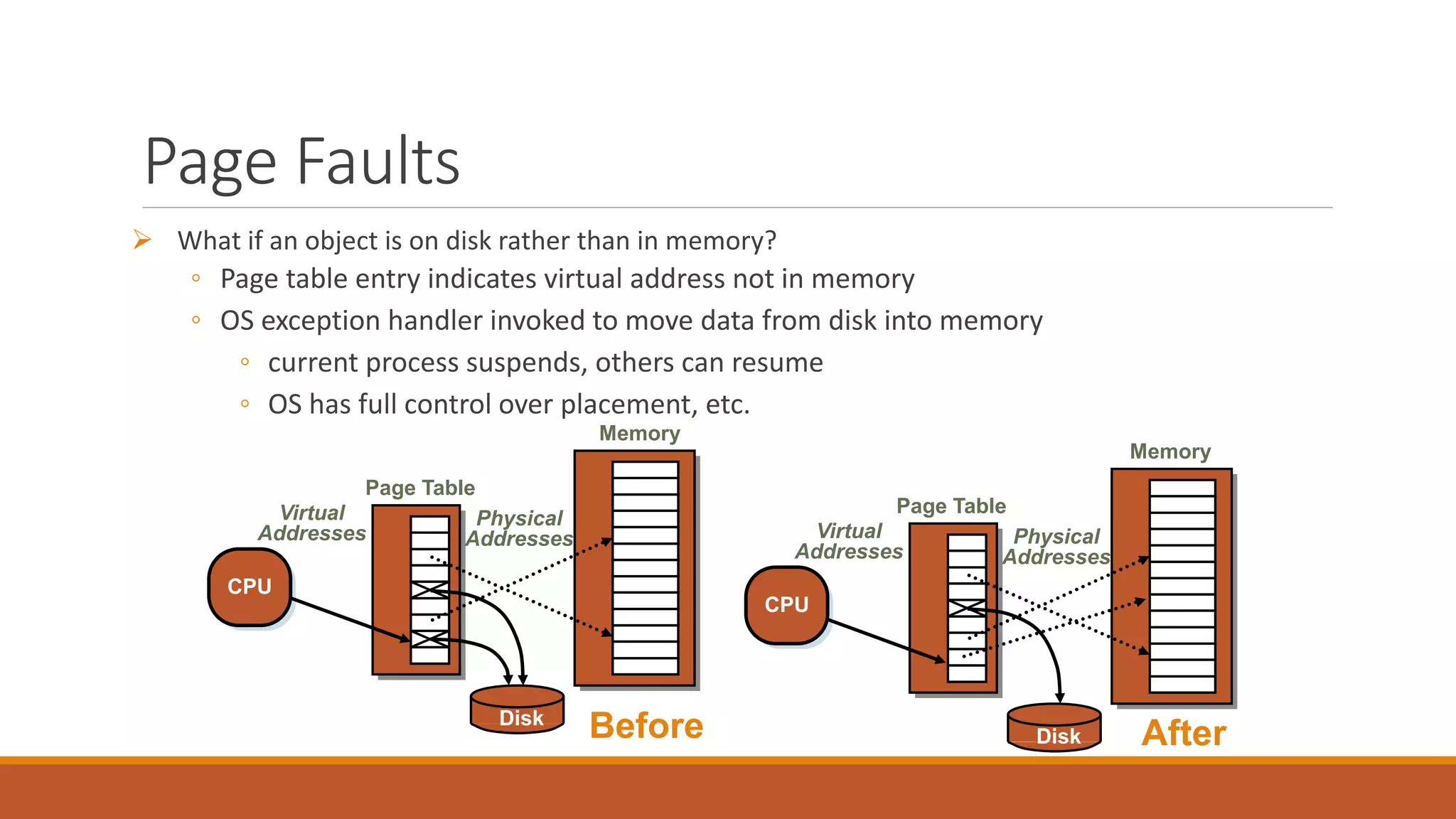

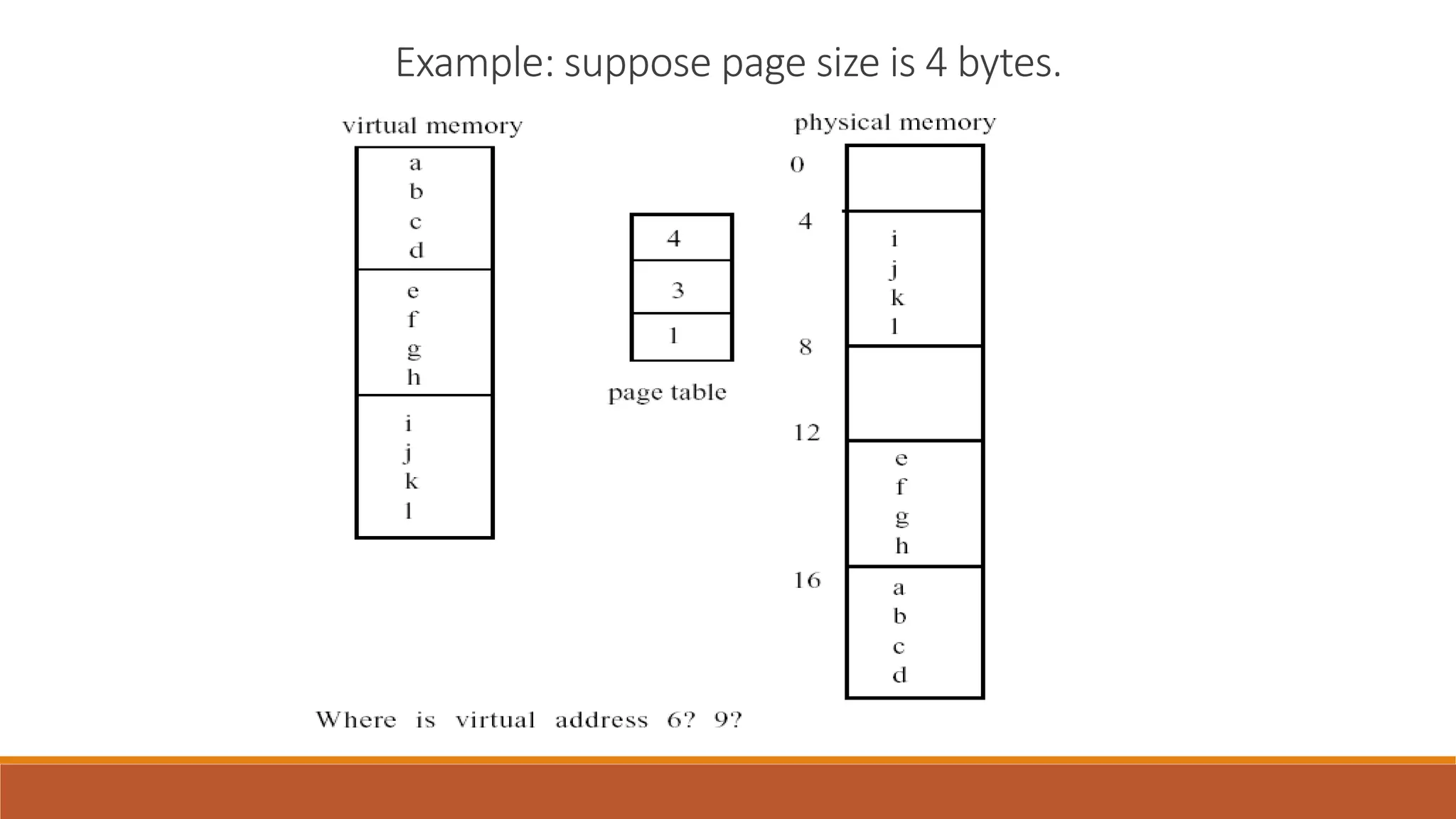

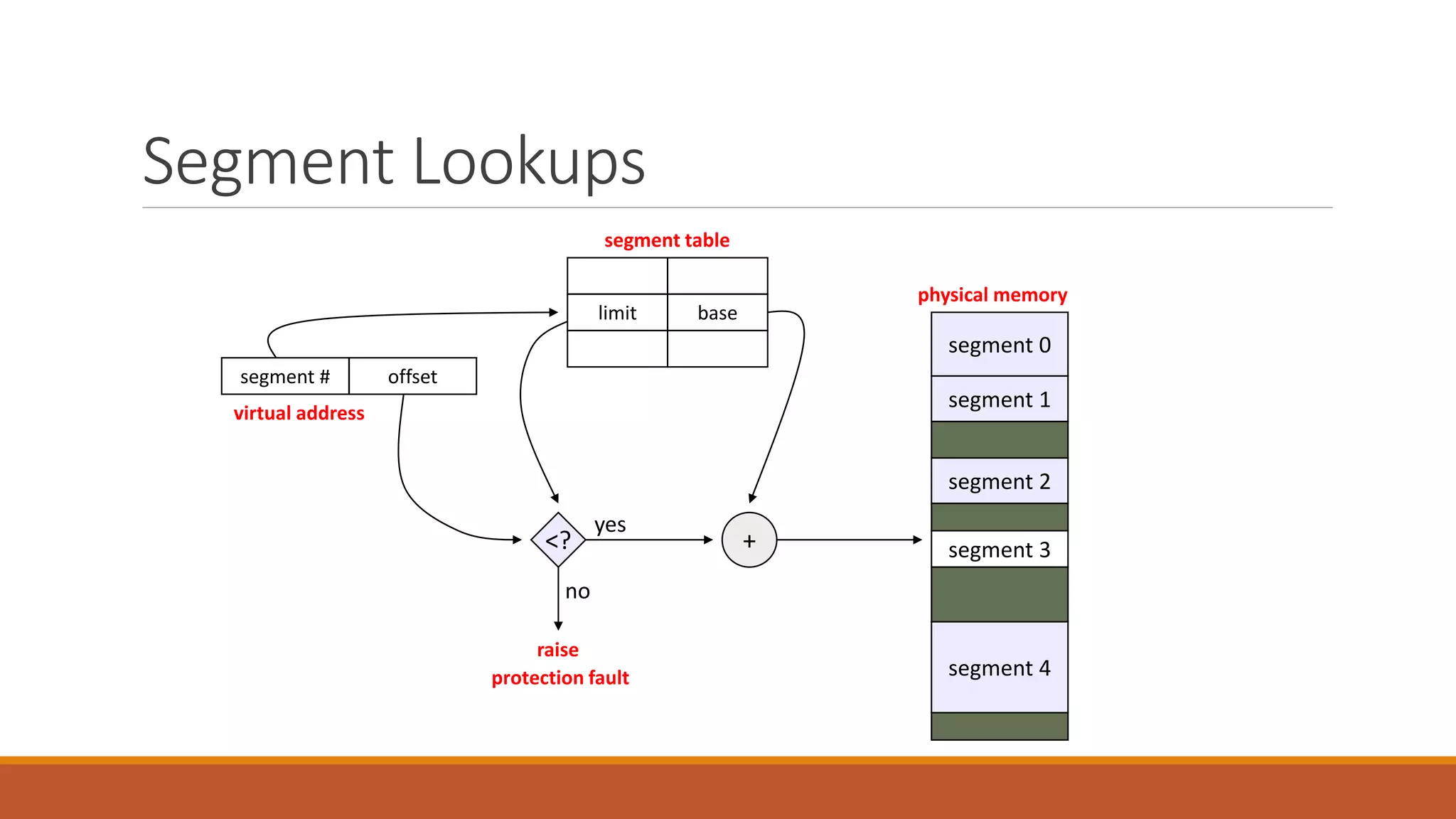

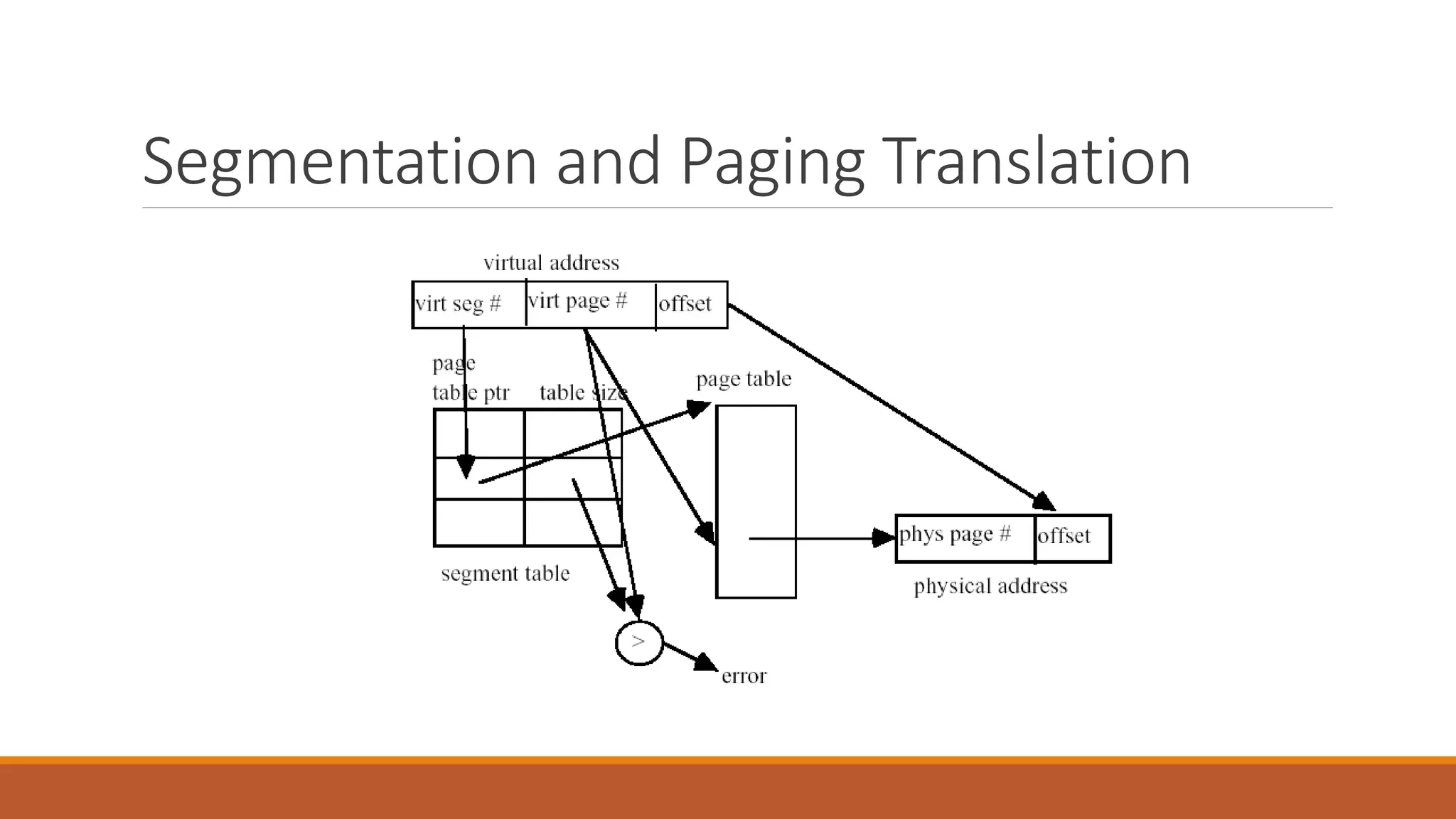

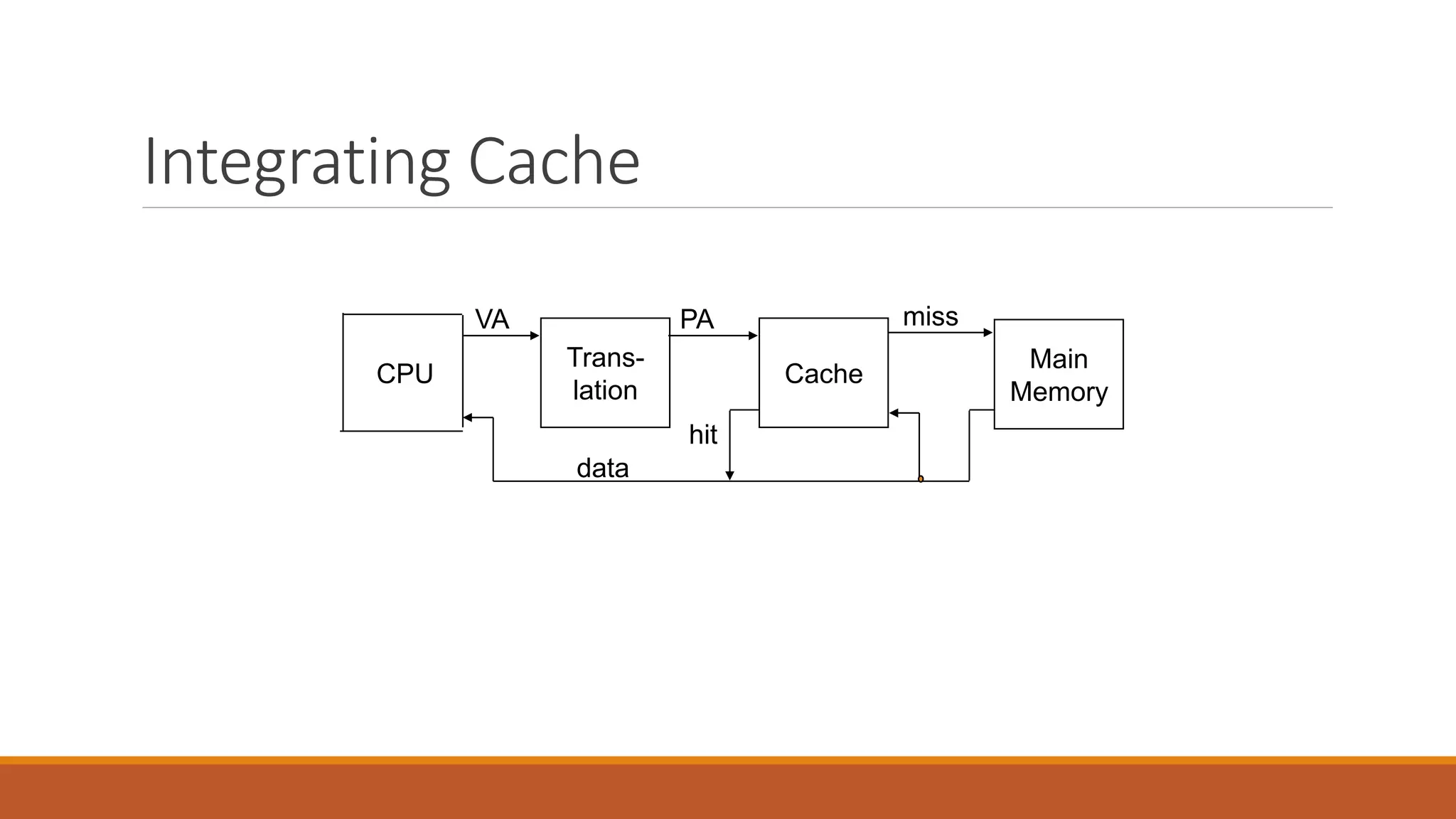

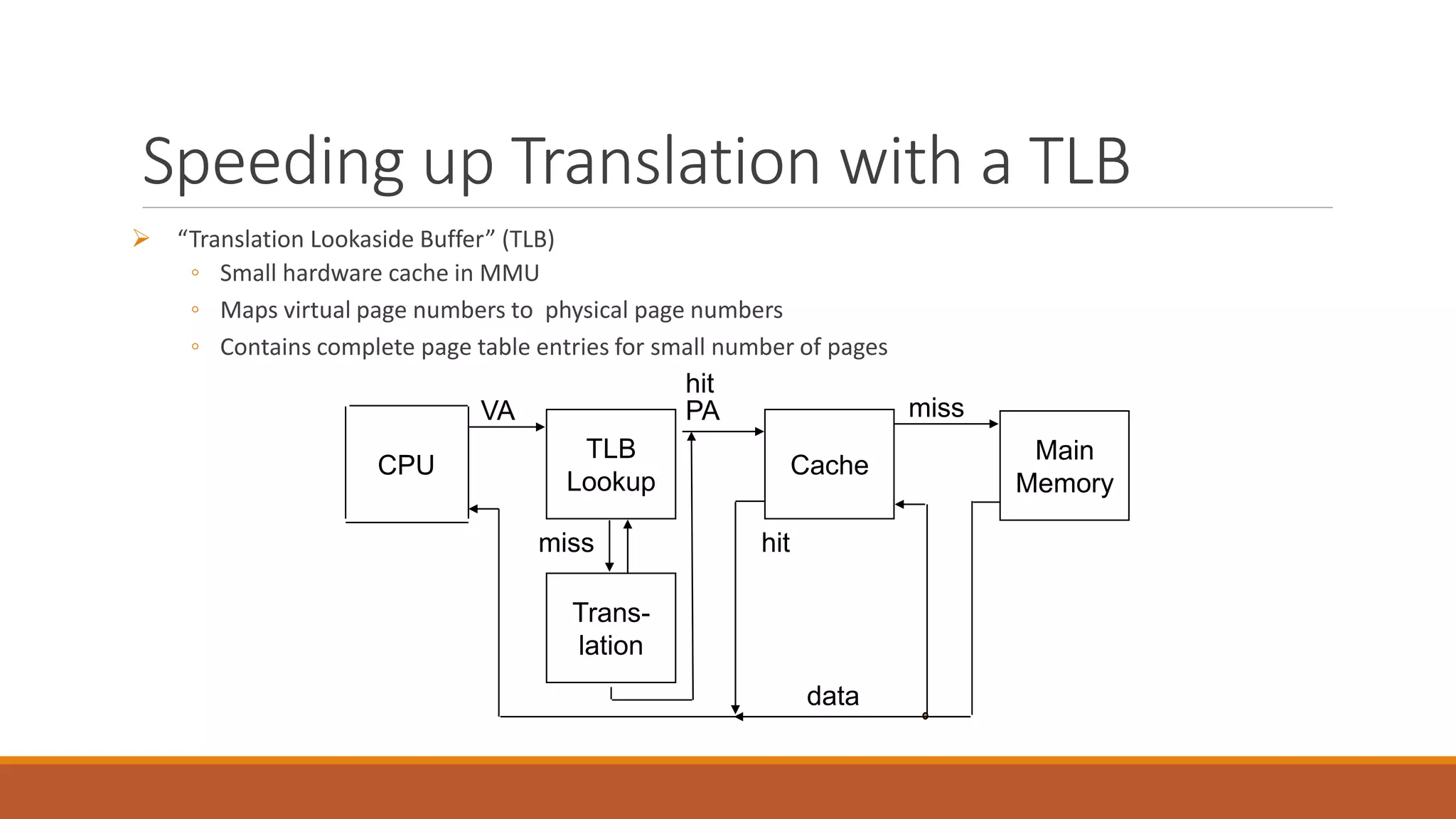

Virtual memory allows programs to execute without requiring their entire address space to be resident in physical memory. It uses virtual addresses that are translated to physical addresses by the hardware. This translation occurs via page tables managed by the operating system. When a virtual address is accessed, its virtual page number is used as an index into the page table to obtain the corresponding physical page frame number. If the page is not in memory, a page fault occurs and the OS handles loading it from disk. Paging partitions both physical and virtual memory into fixed-sized pages to address fragmentation issues. Segmentation further partitions the virtual address space into logical segments. Hardware support for segmentation involves a segment table containing base/limit pairs for each segment. Translation lookaside buffers