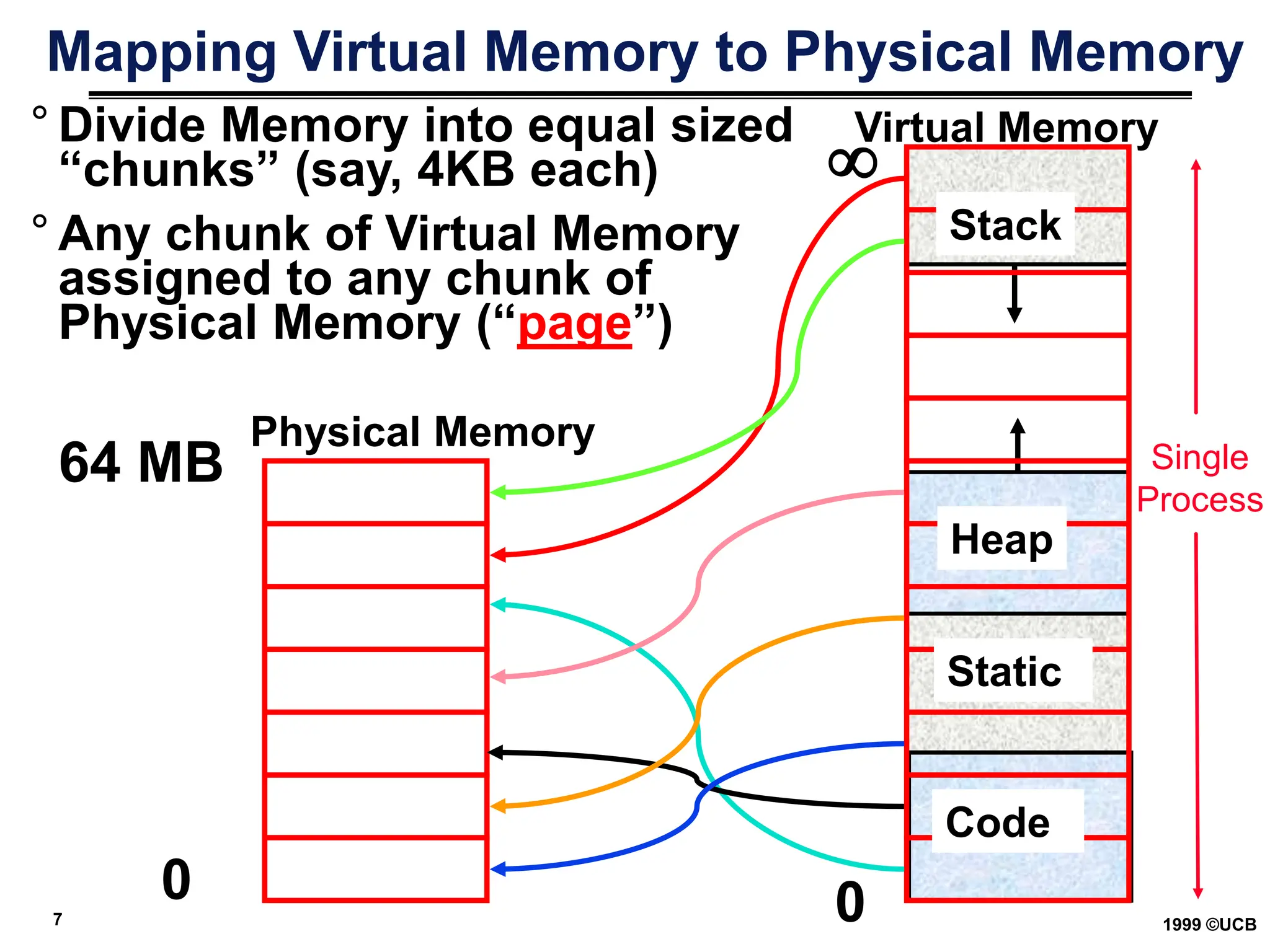

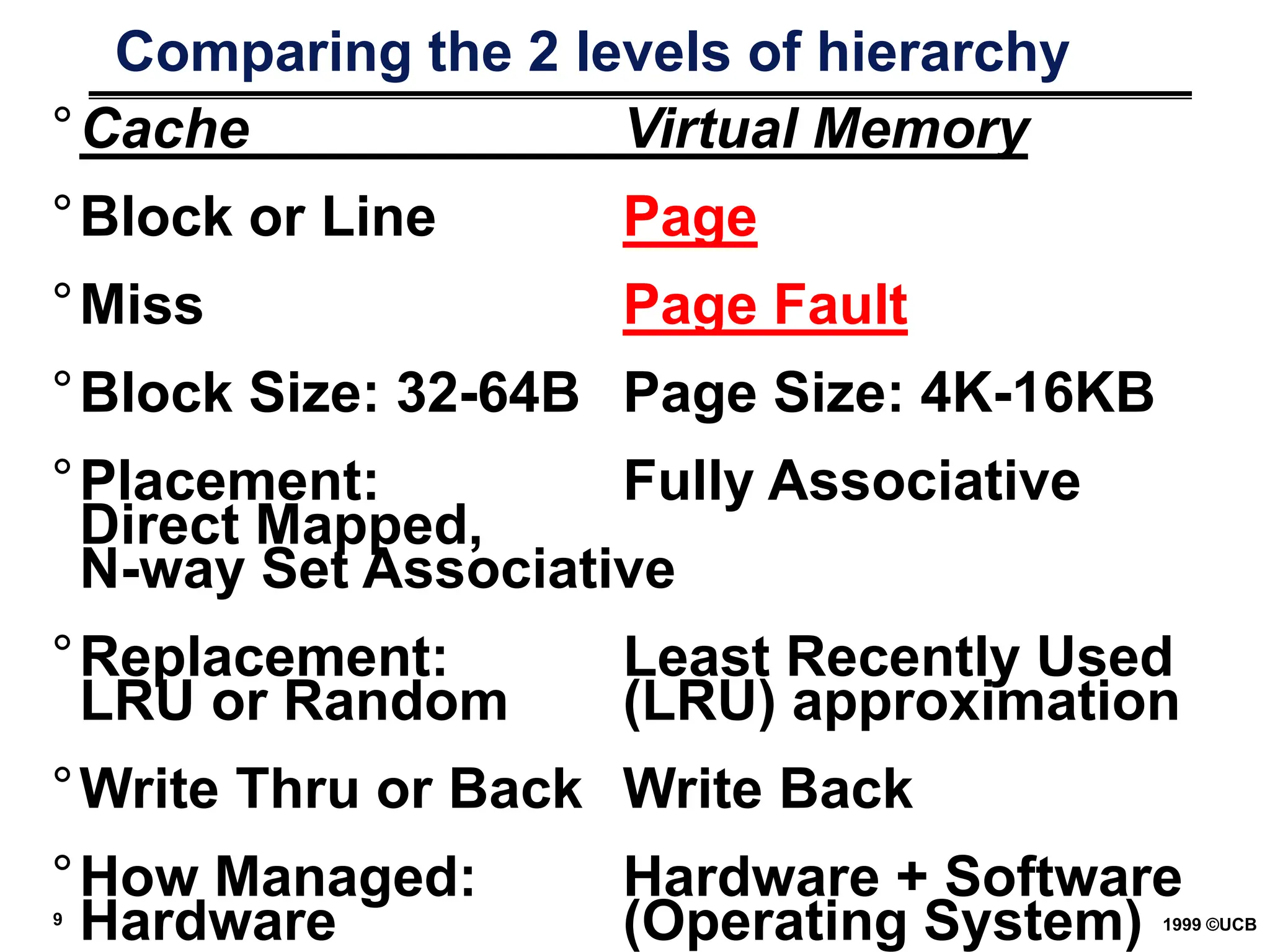

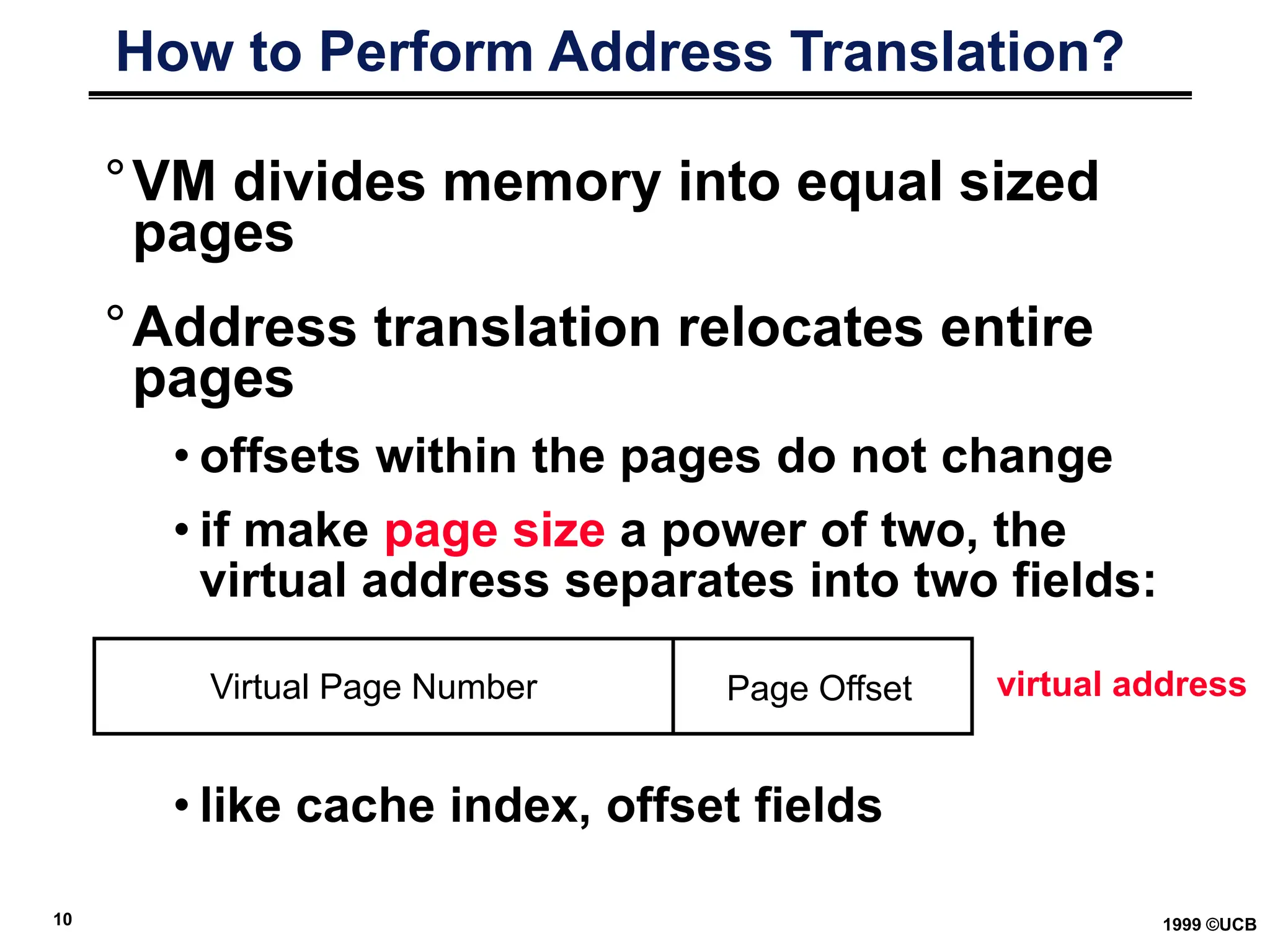

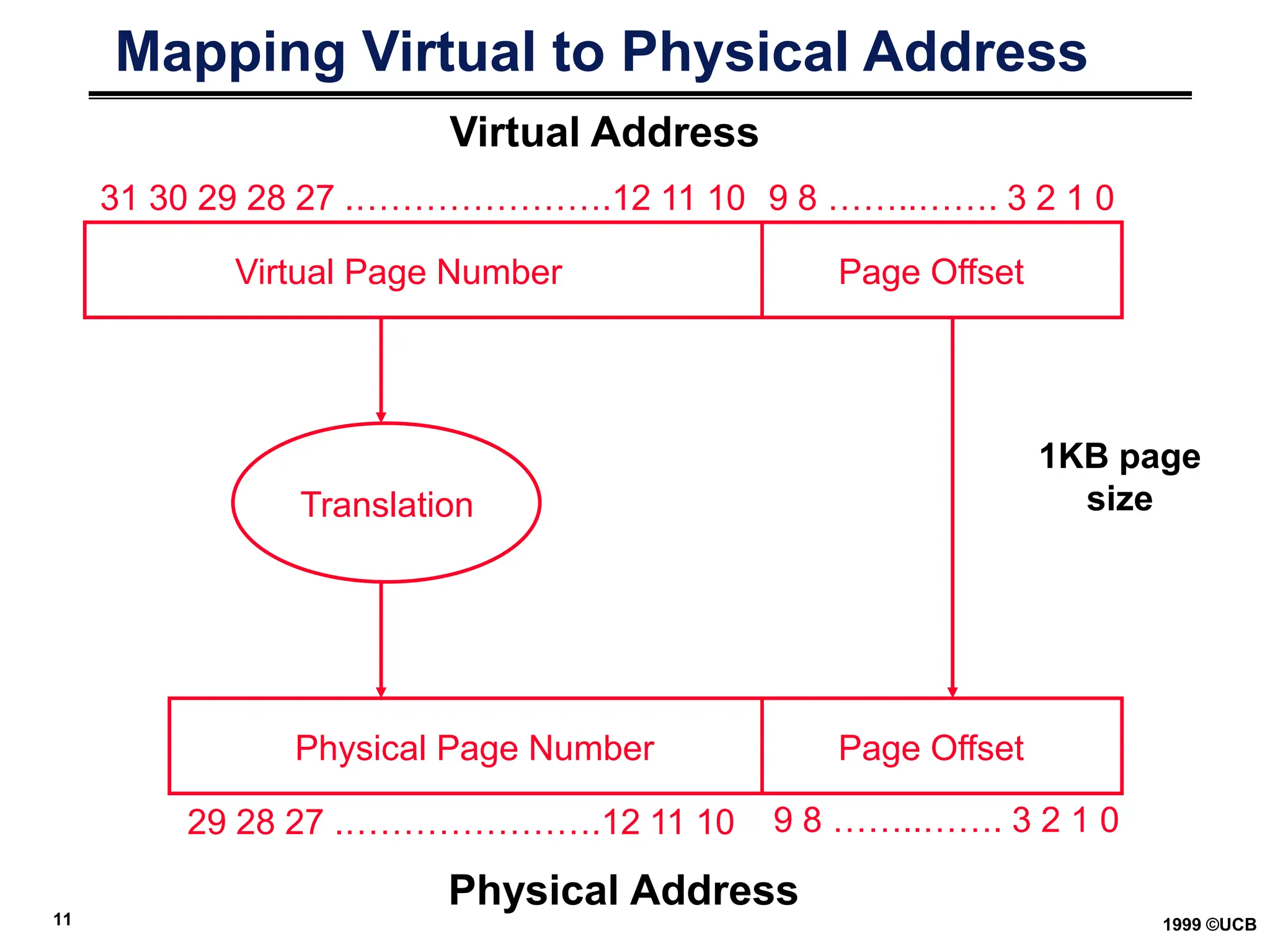

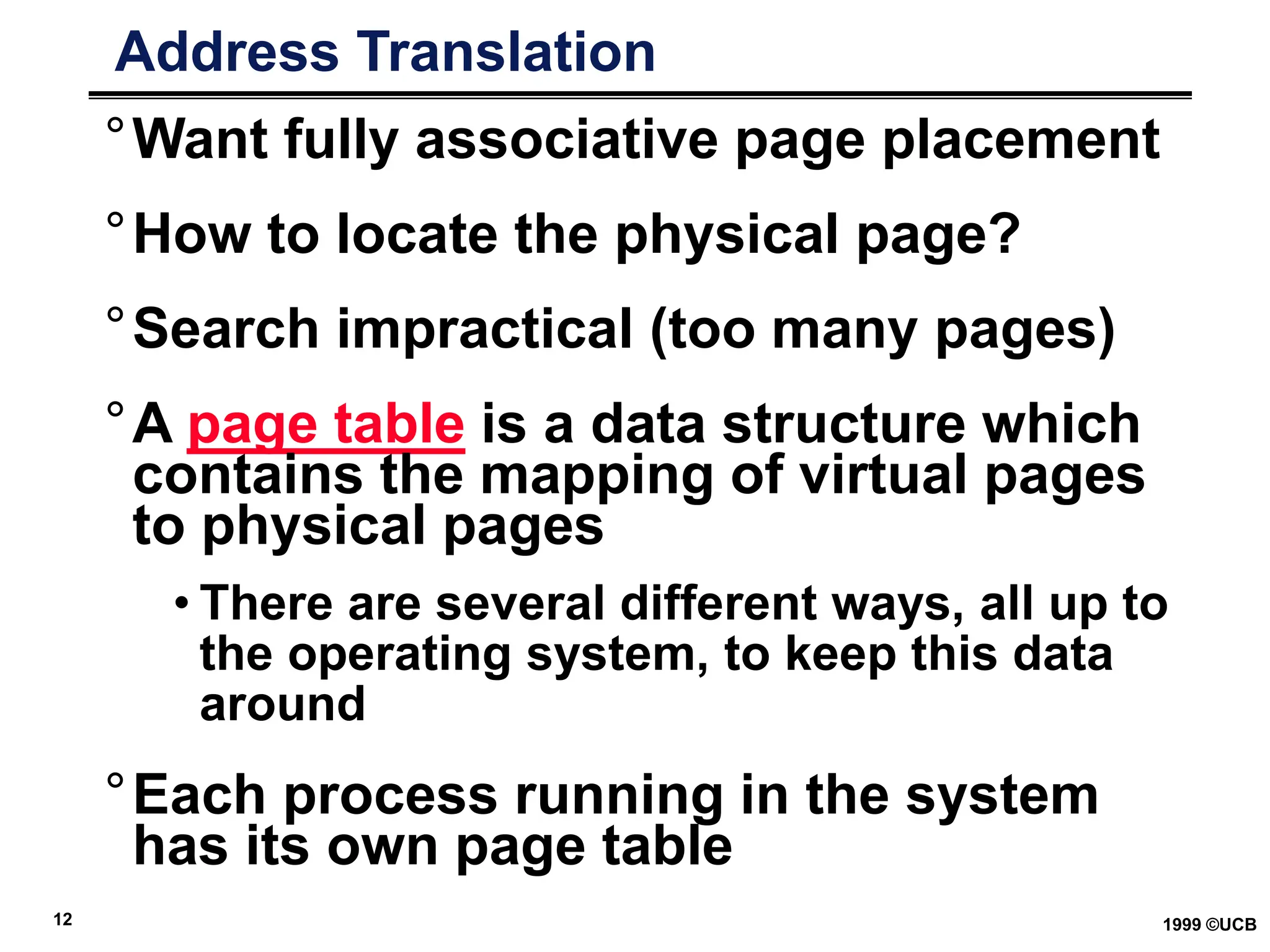

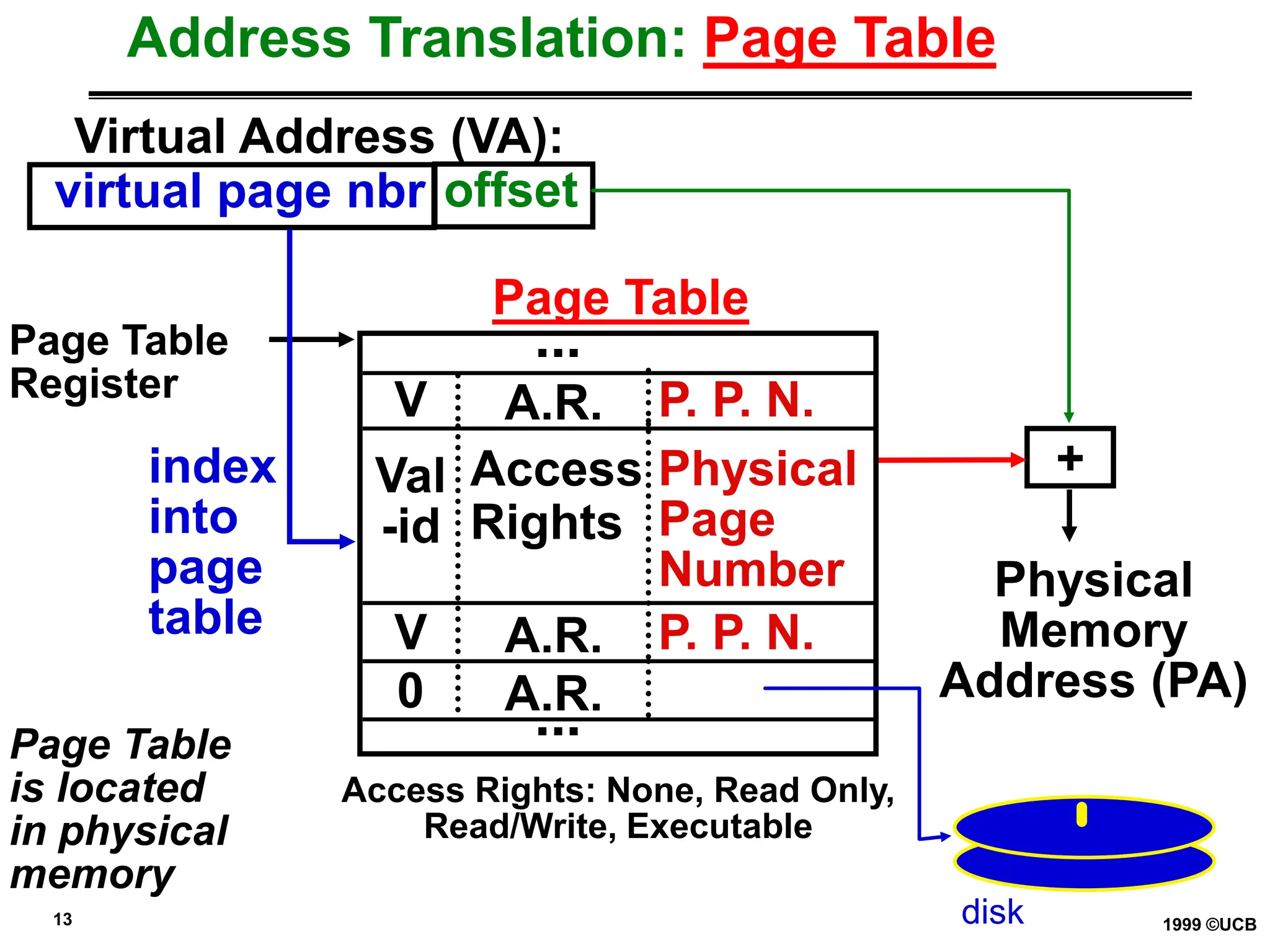

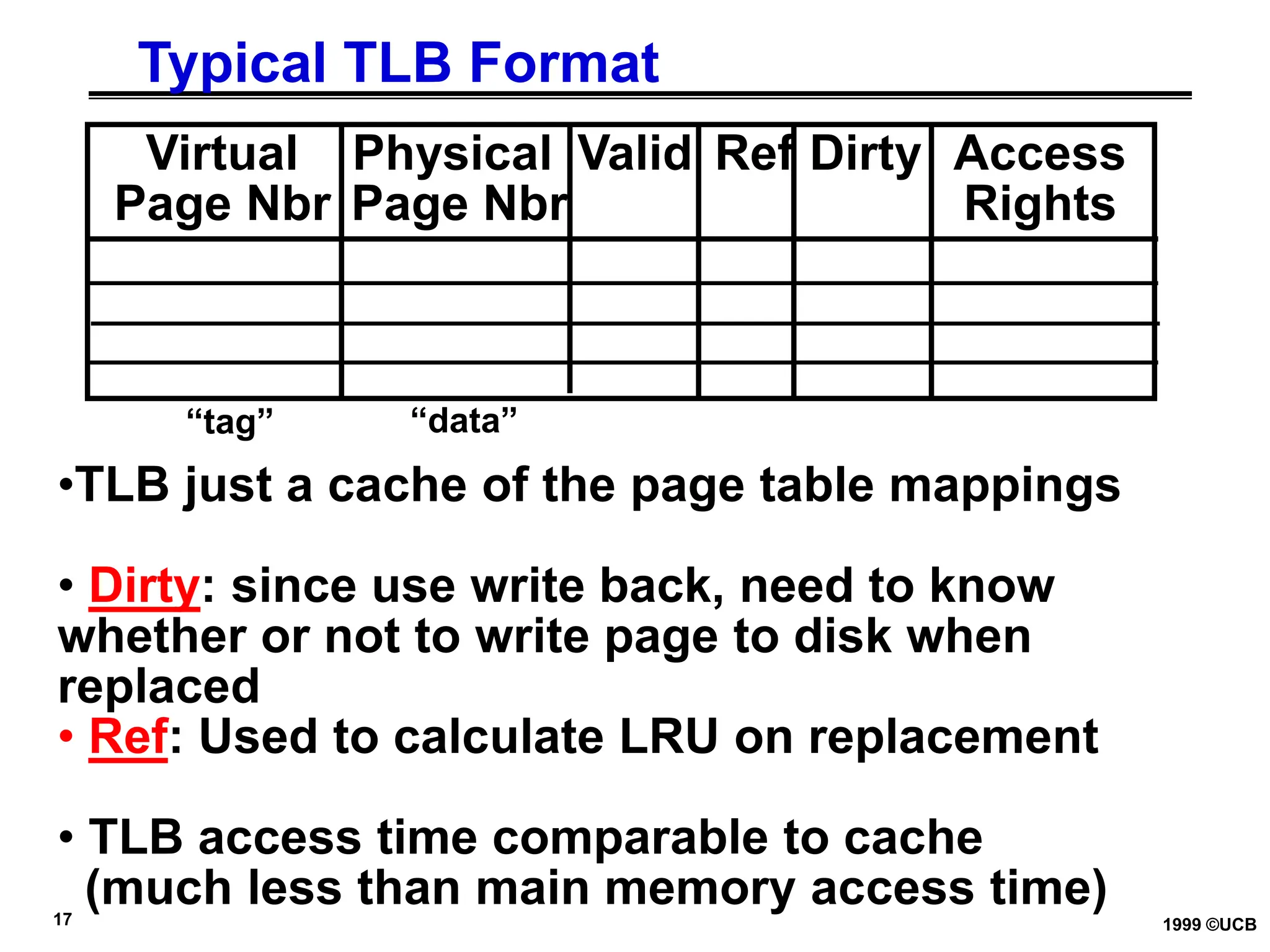

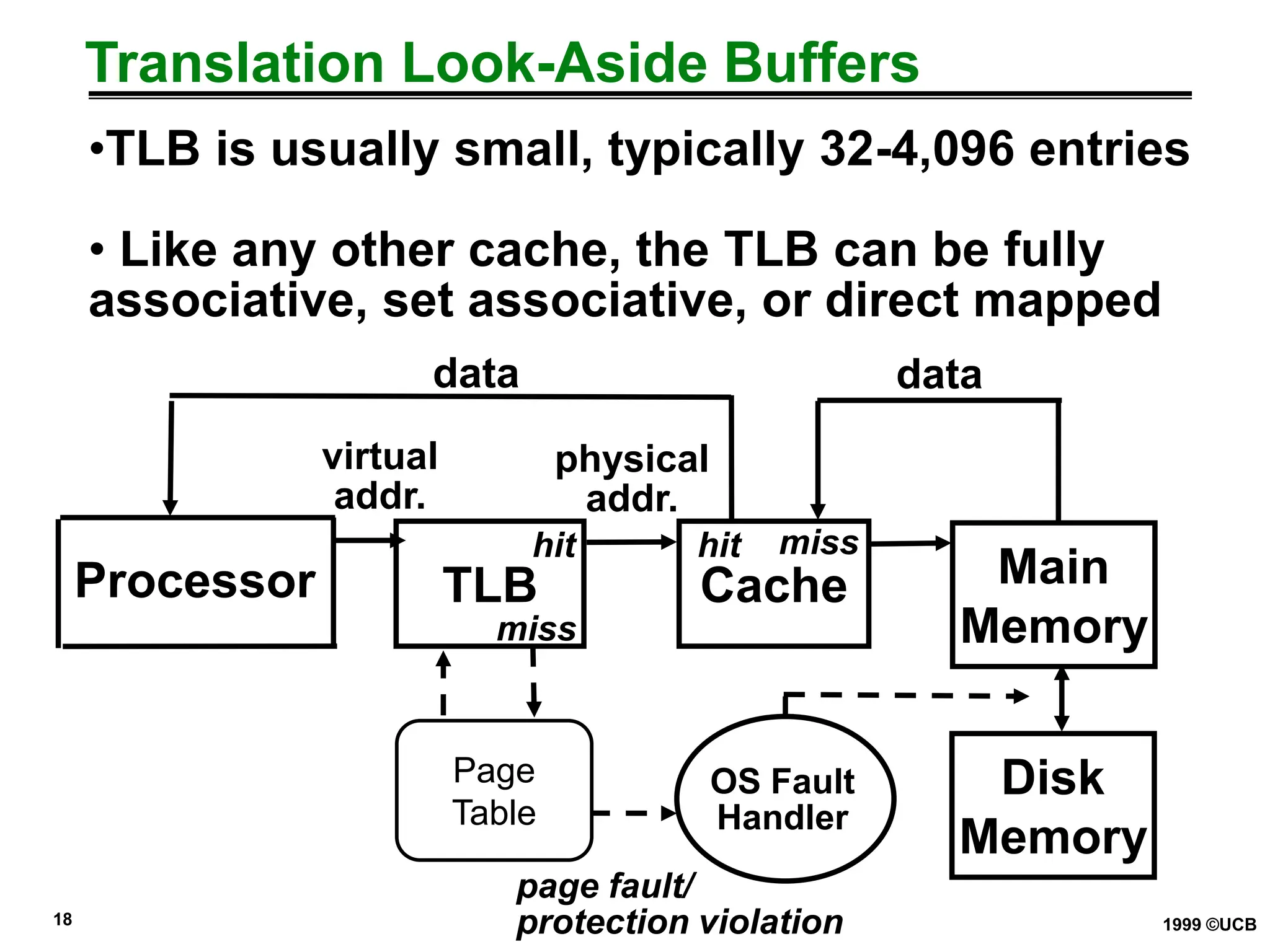

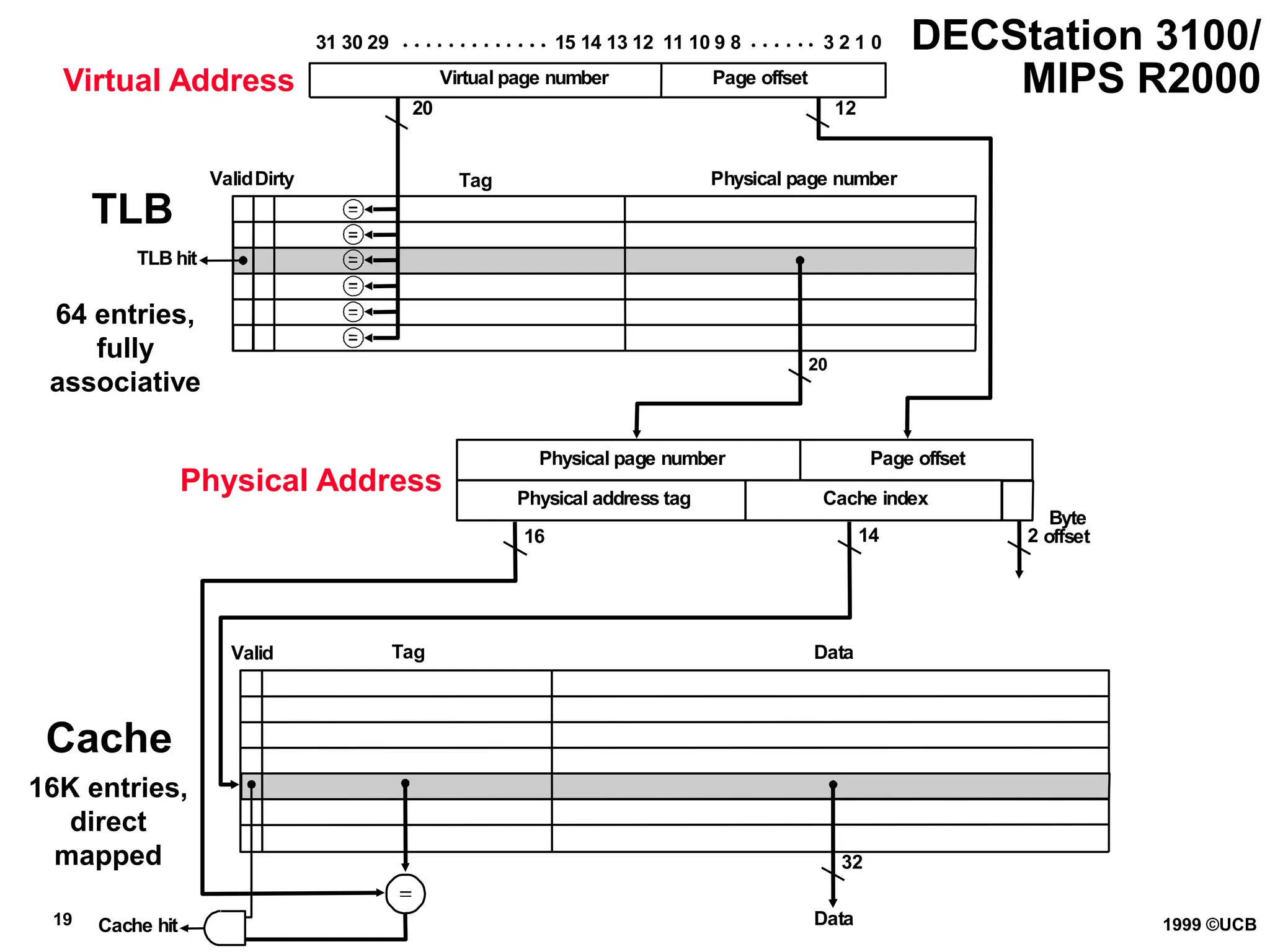

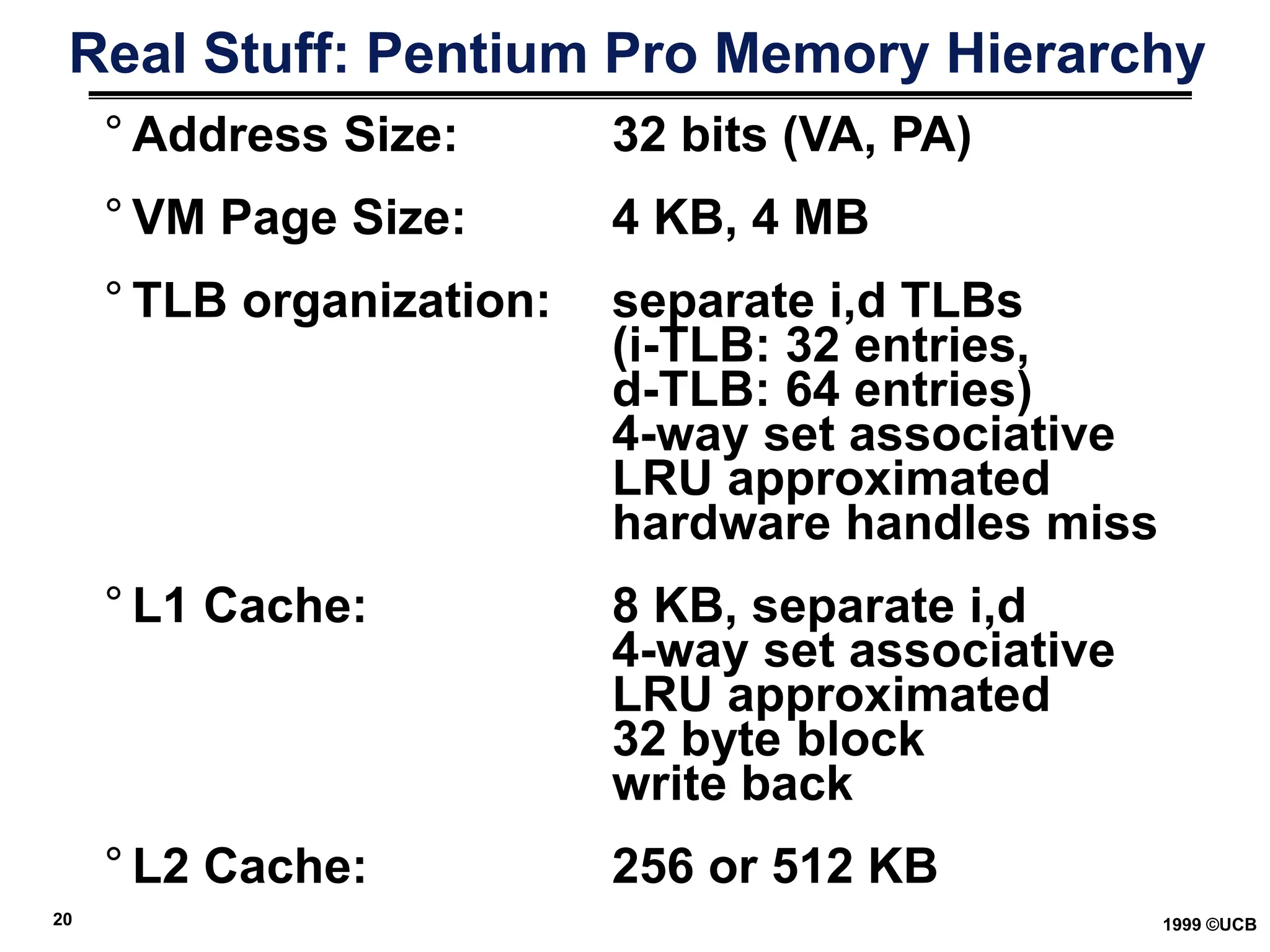

This document discusses virtual memory and memory hierarchies. It describes how virtual memory uses page tables to map virtual addresses to physical addresses, allowing processes to access memory in pages that may be stored in main memory or on disk. It also discusses how translation lookaside buffers (TLBs) are used to cache translations from virtual to physical addresses to speed up the translation process, acting as a cache for the page tables stored in physical memory.