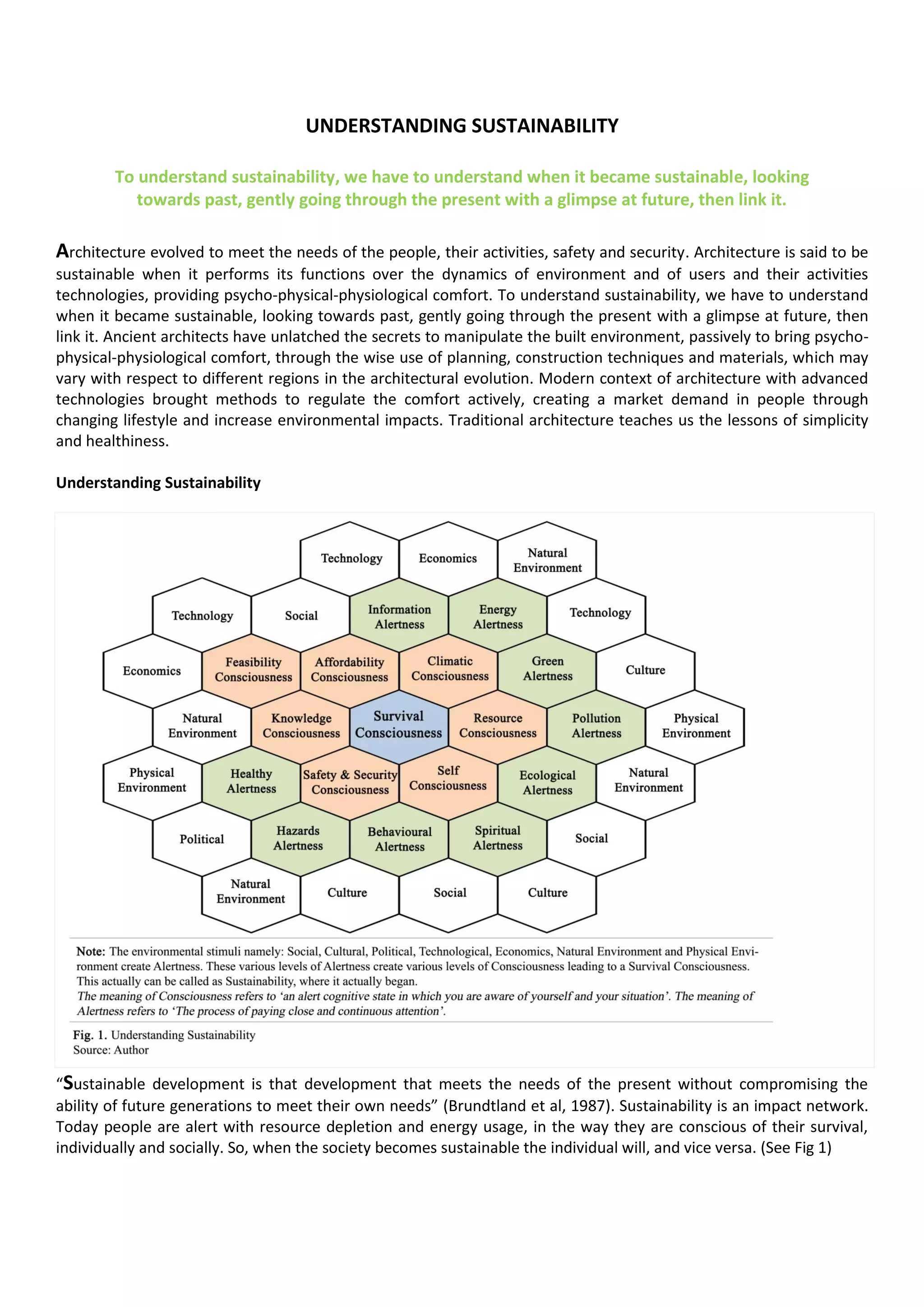

The document discusses sustainability in architecture from traditional and modern perspectives. It summarizes that traditional architecture was more sustainable due to use of local materials, passive design techniques, joint family structures, and production of own resources. However, modern architecture focuses more on artificial comfort through advanced technologies and materials with high embodied energy, leading to less sustainability. While technology is important, traditional principles of simplicity, resource efficiency and climate responsiveness provide lessons for creating sustainable modern architecture.