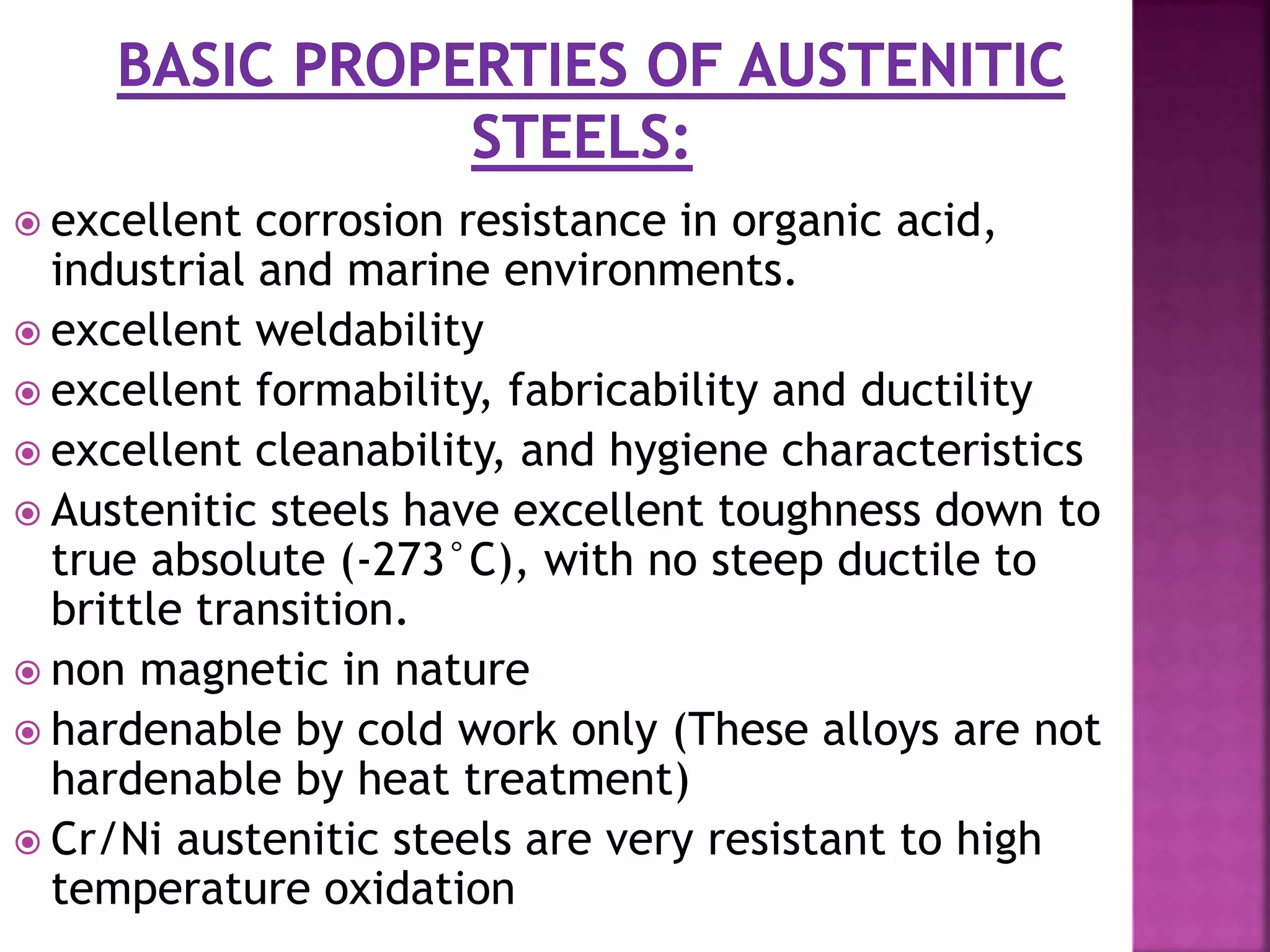

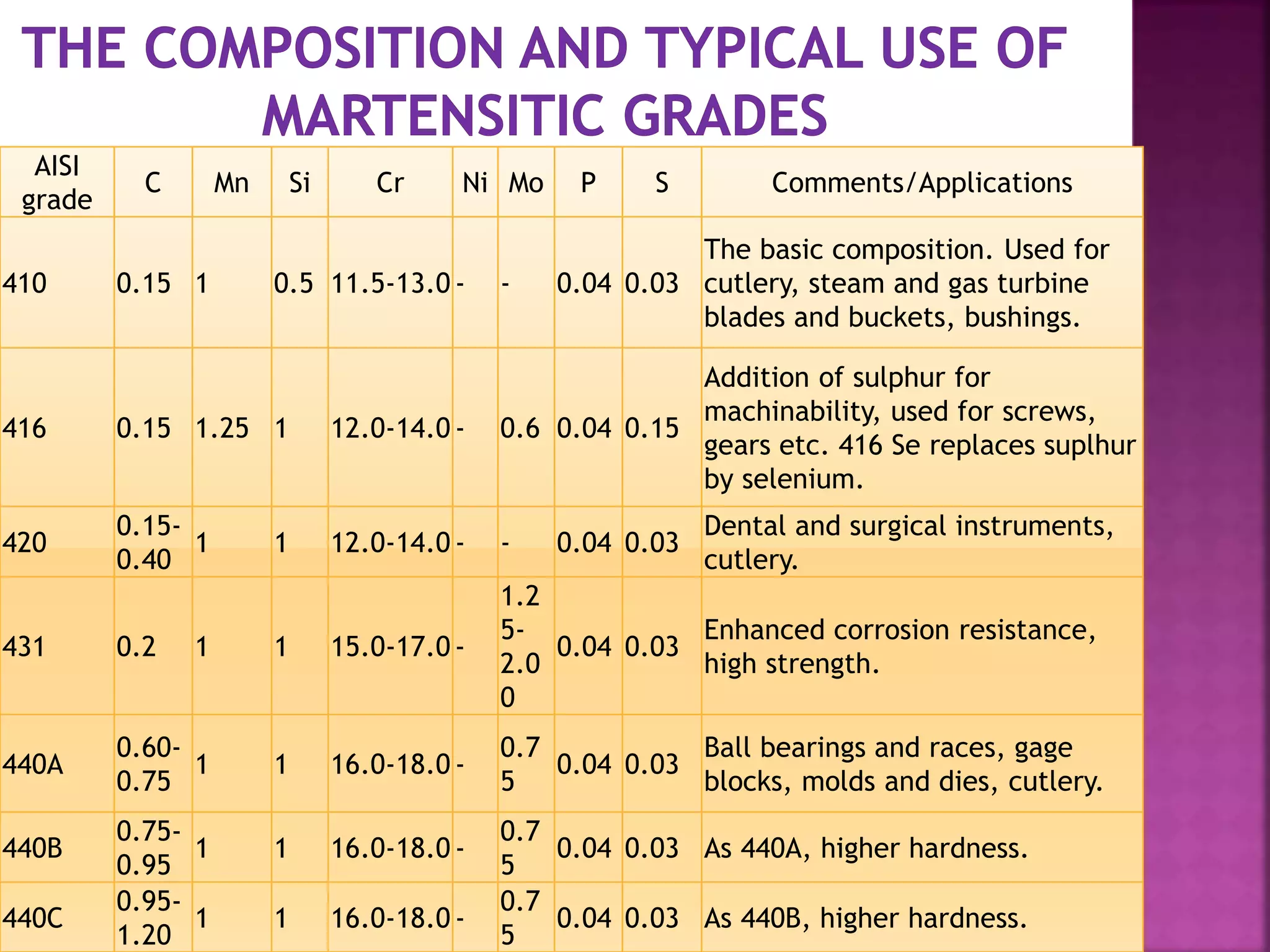

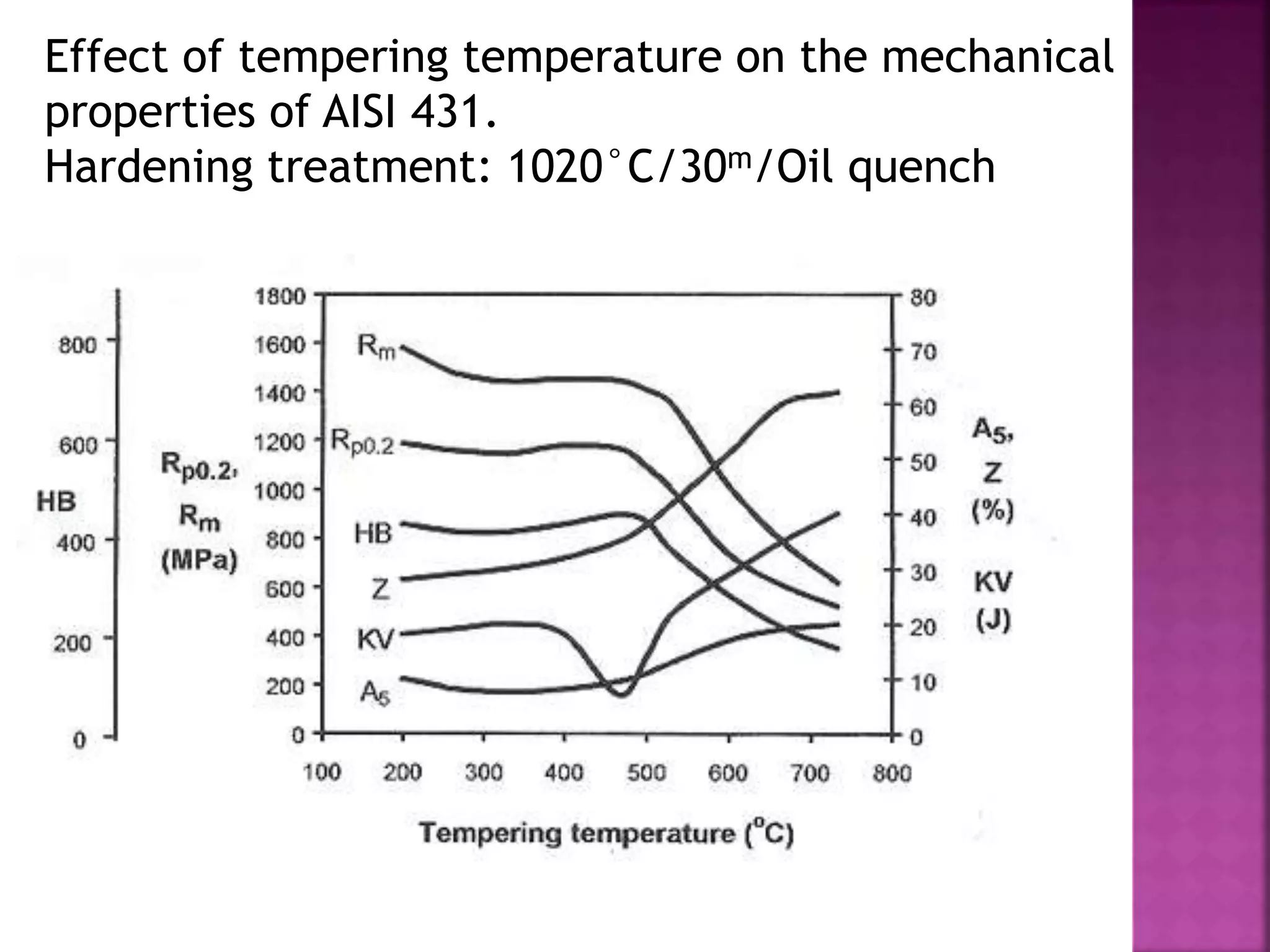

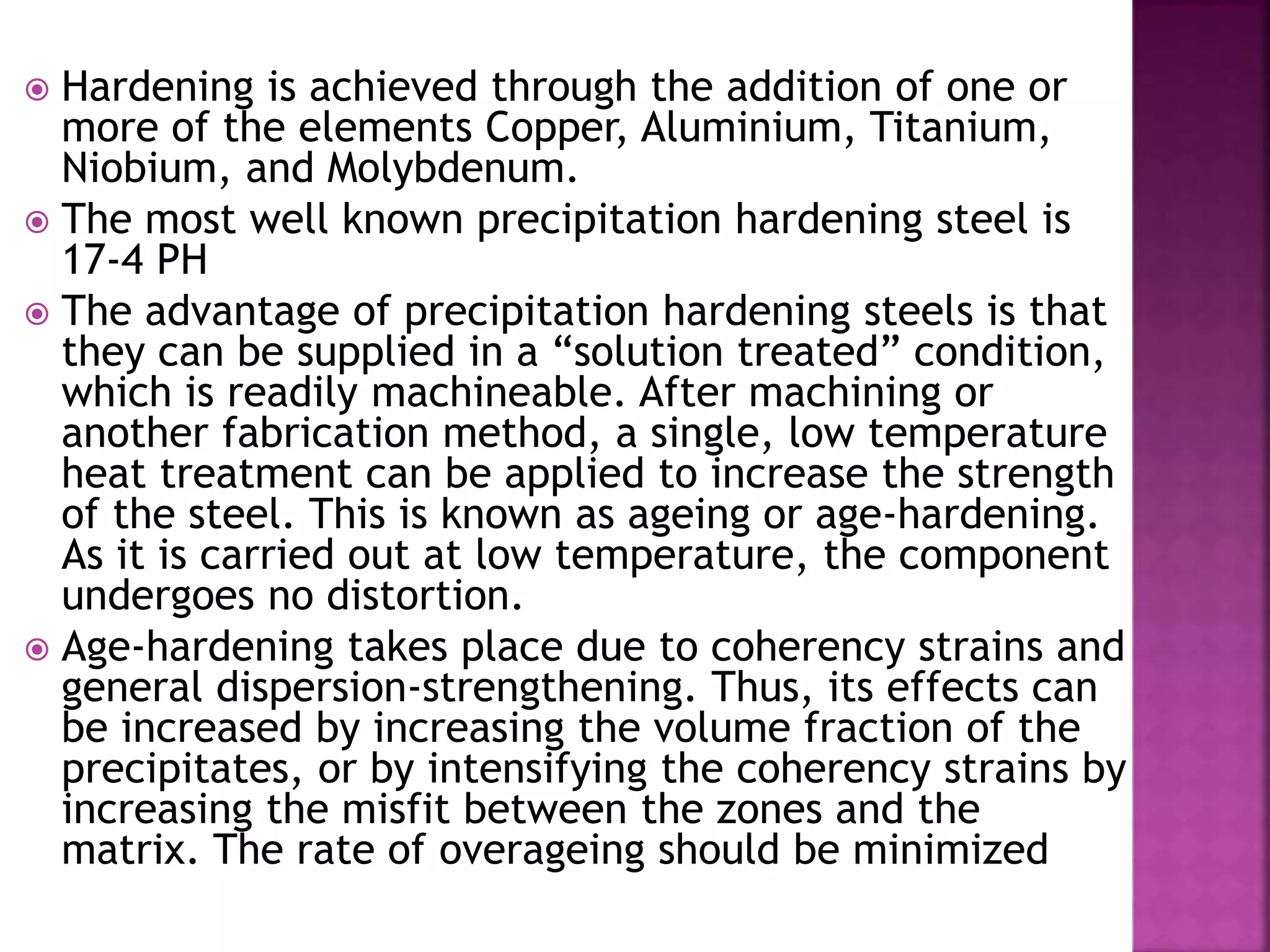

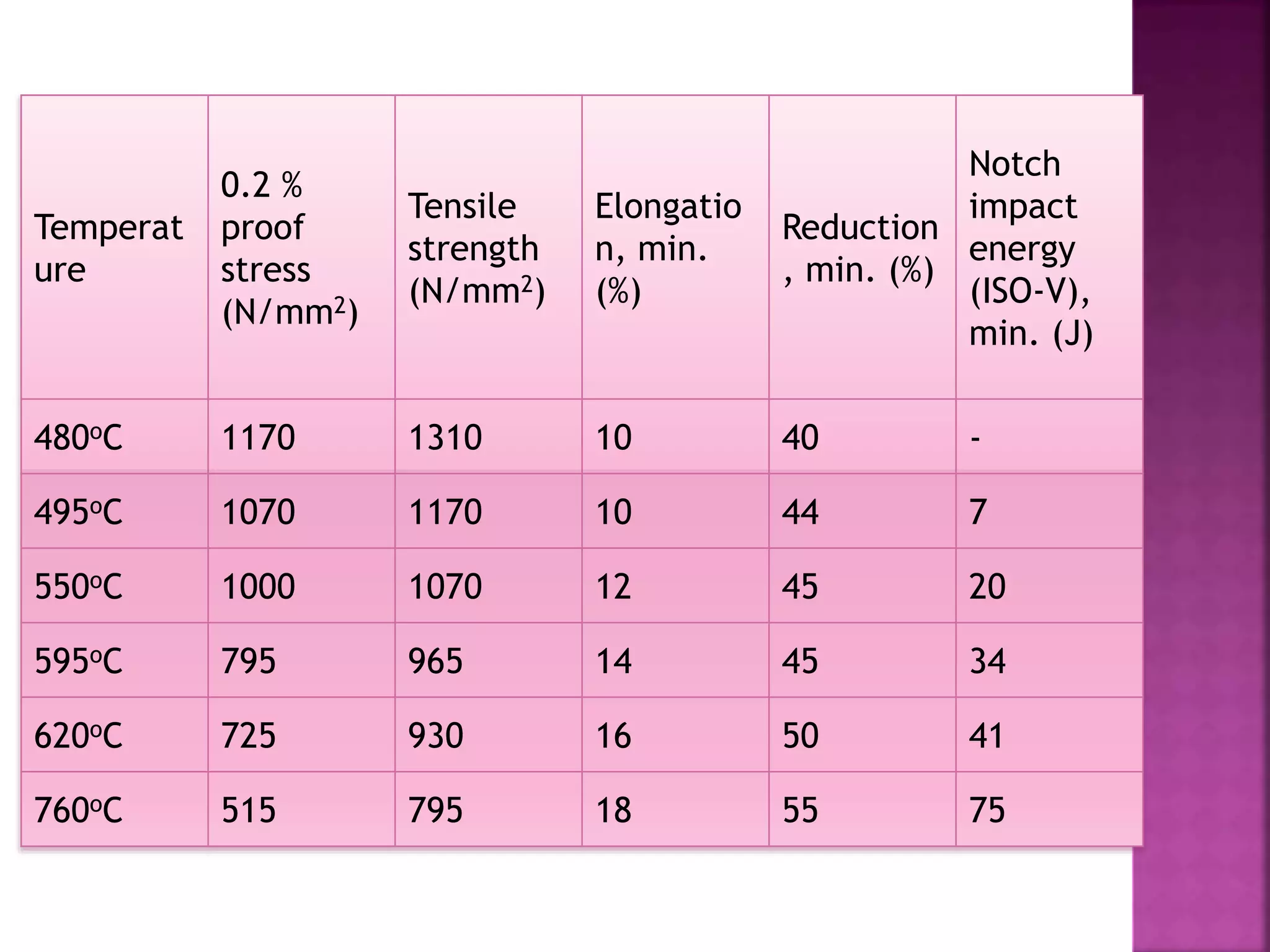

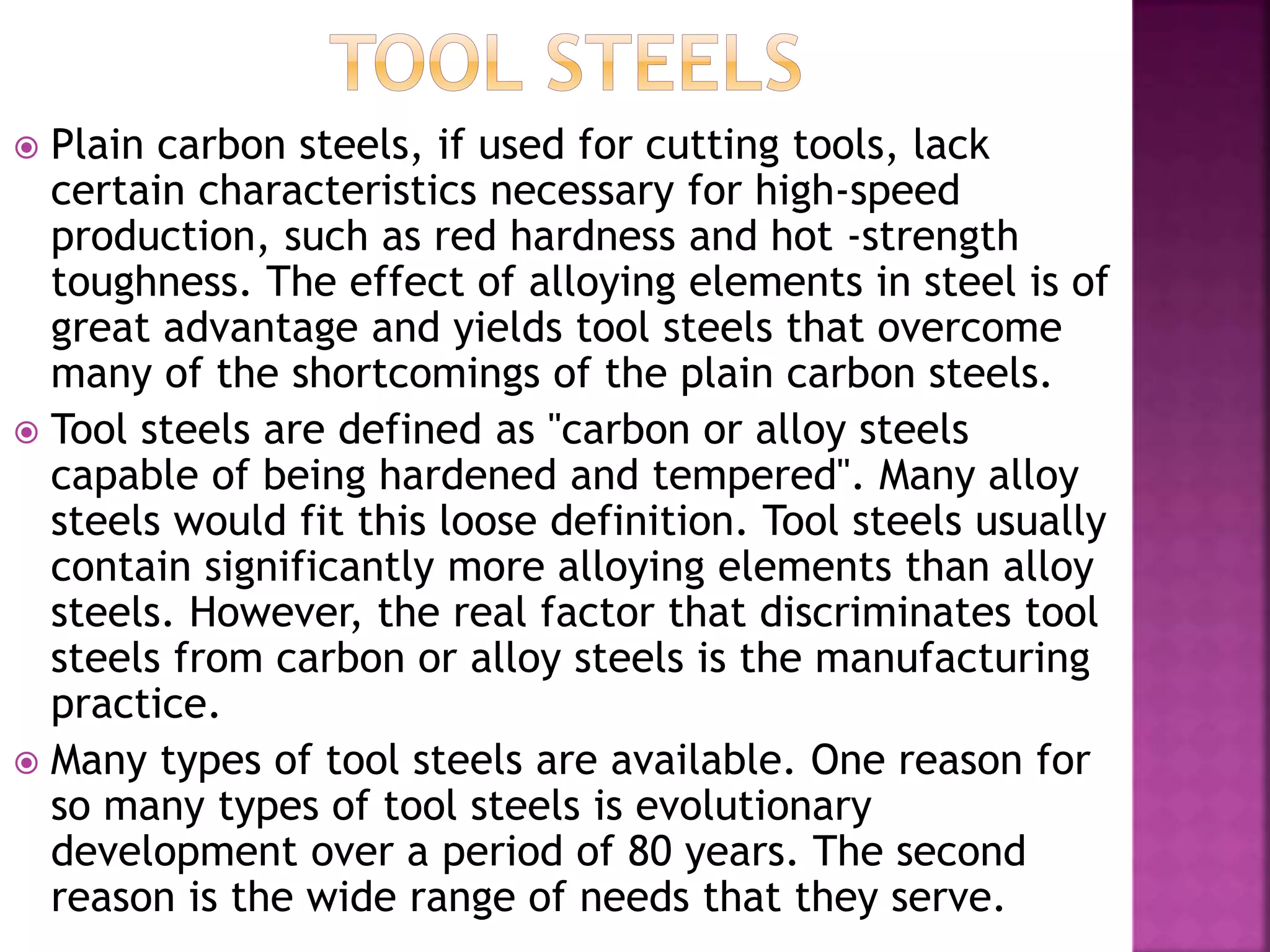

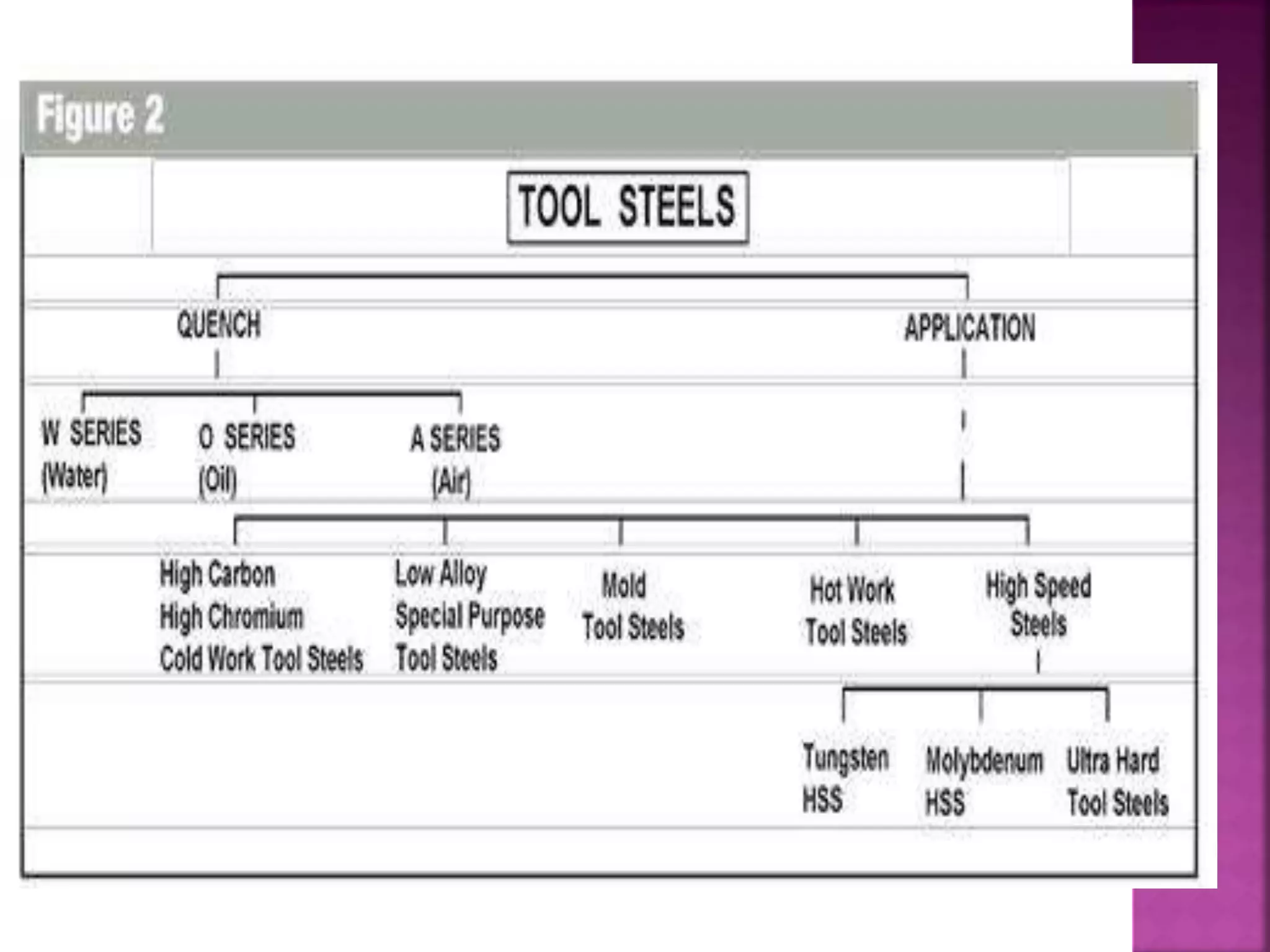

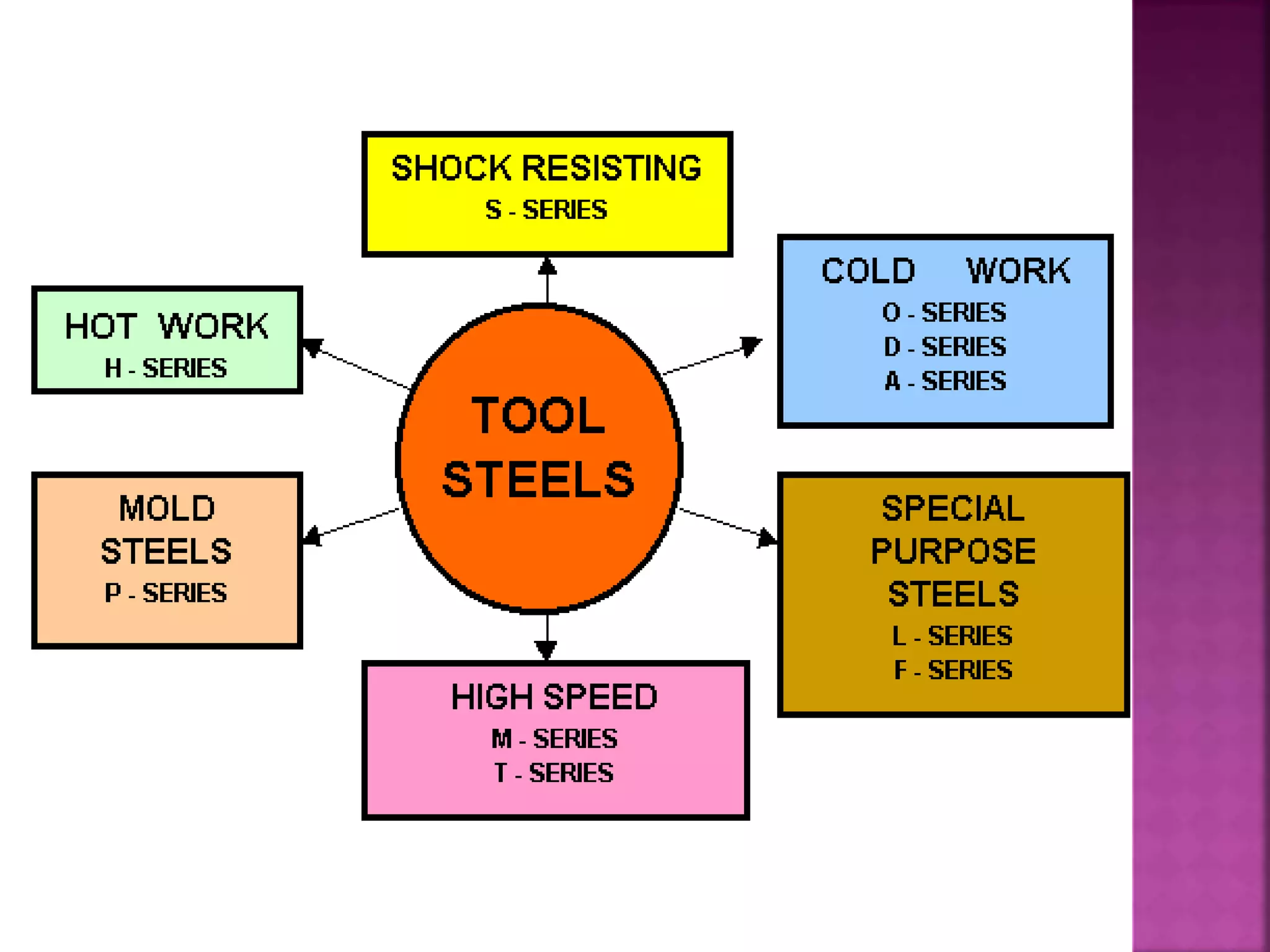

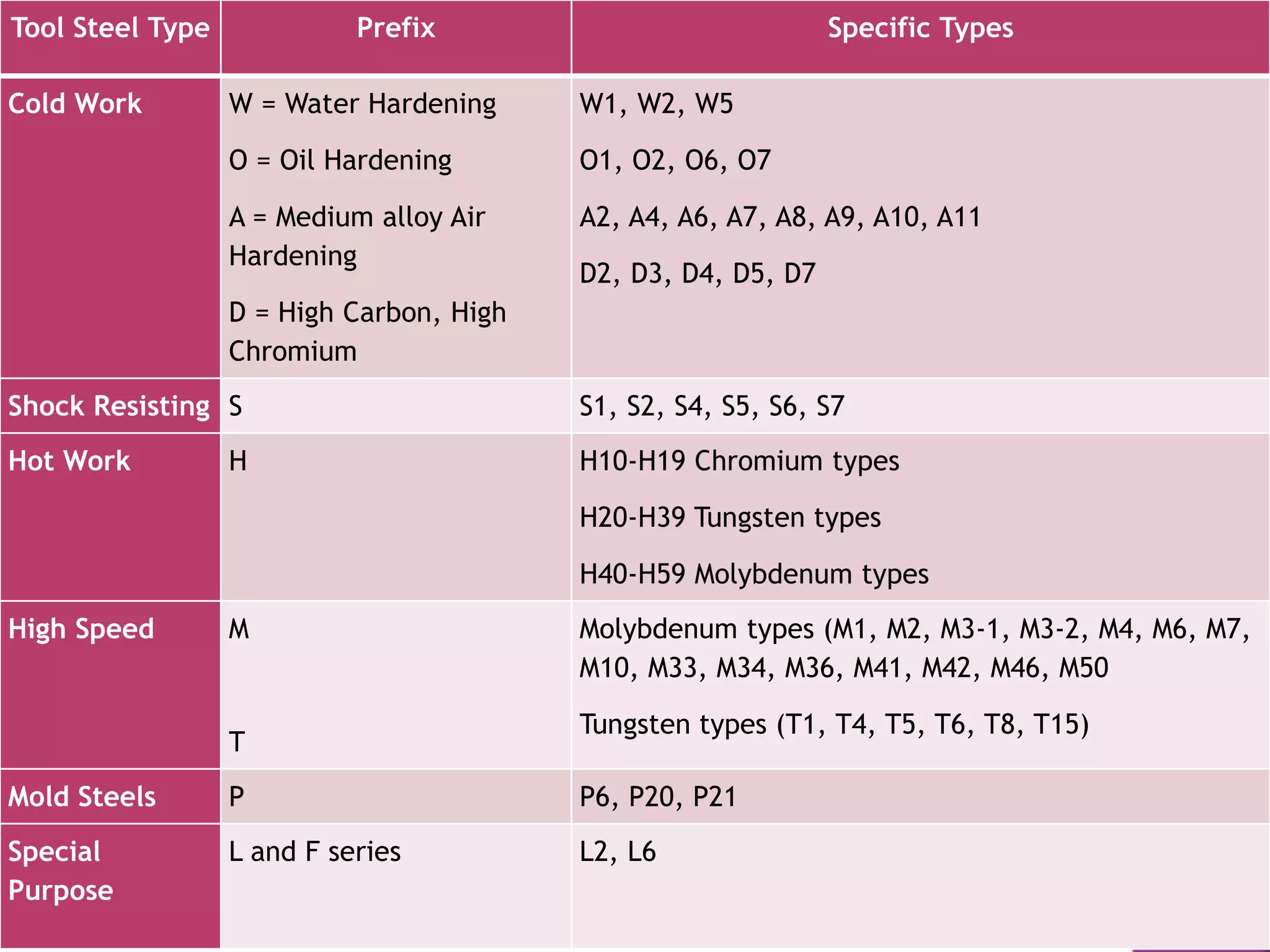

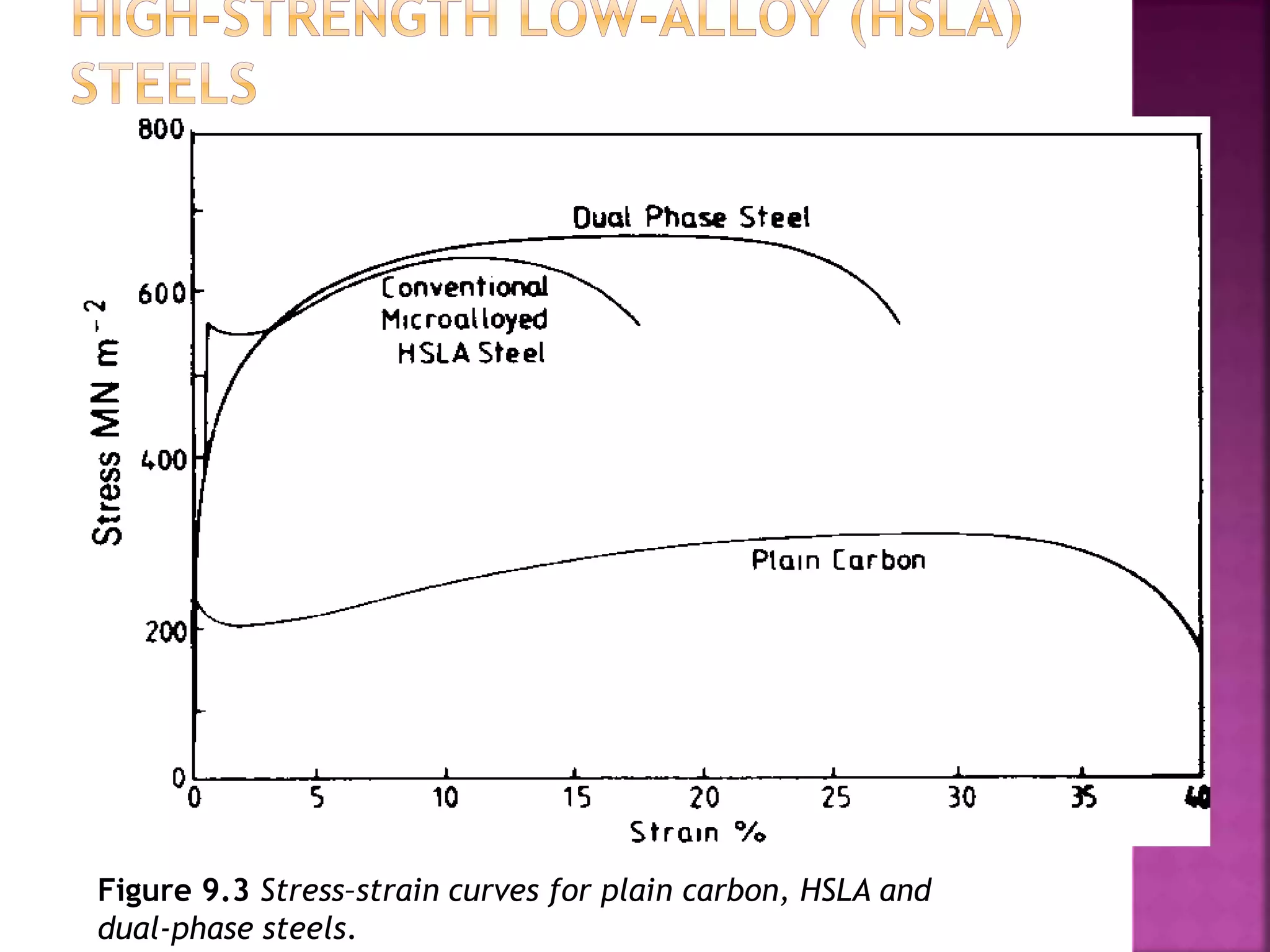

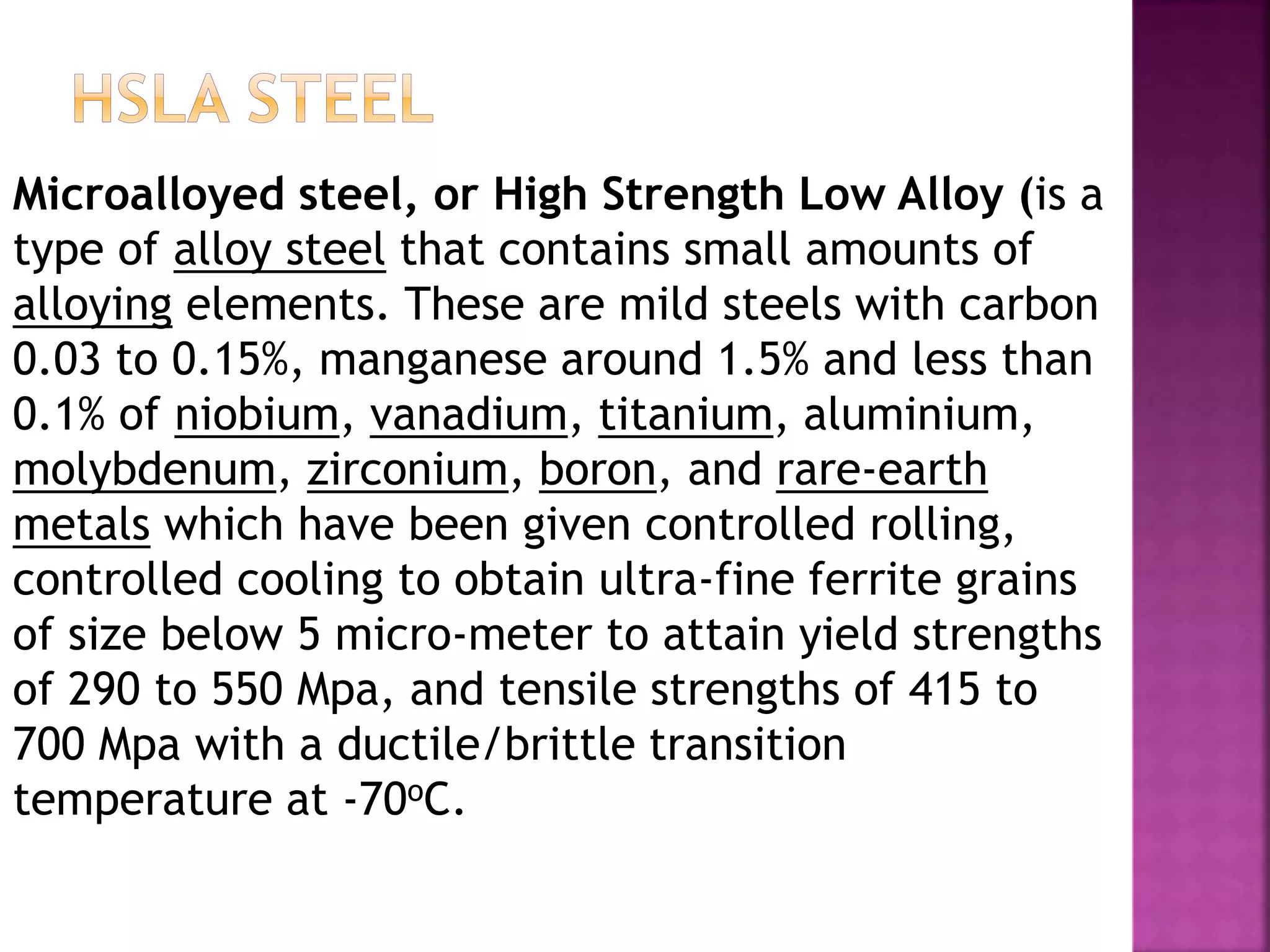

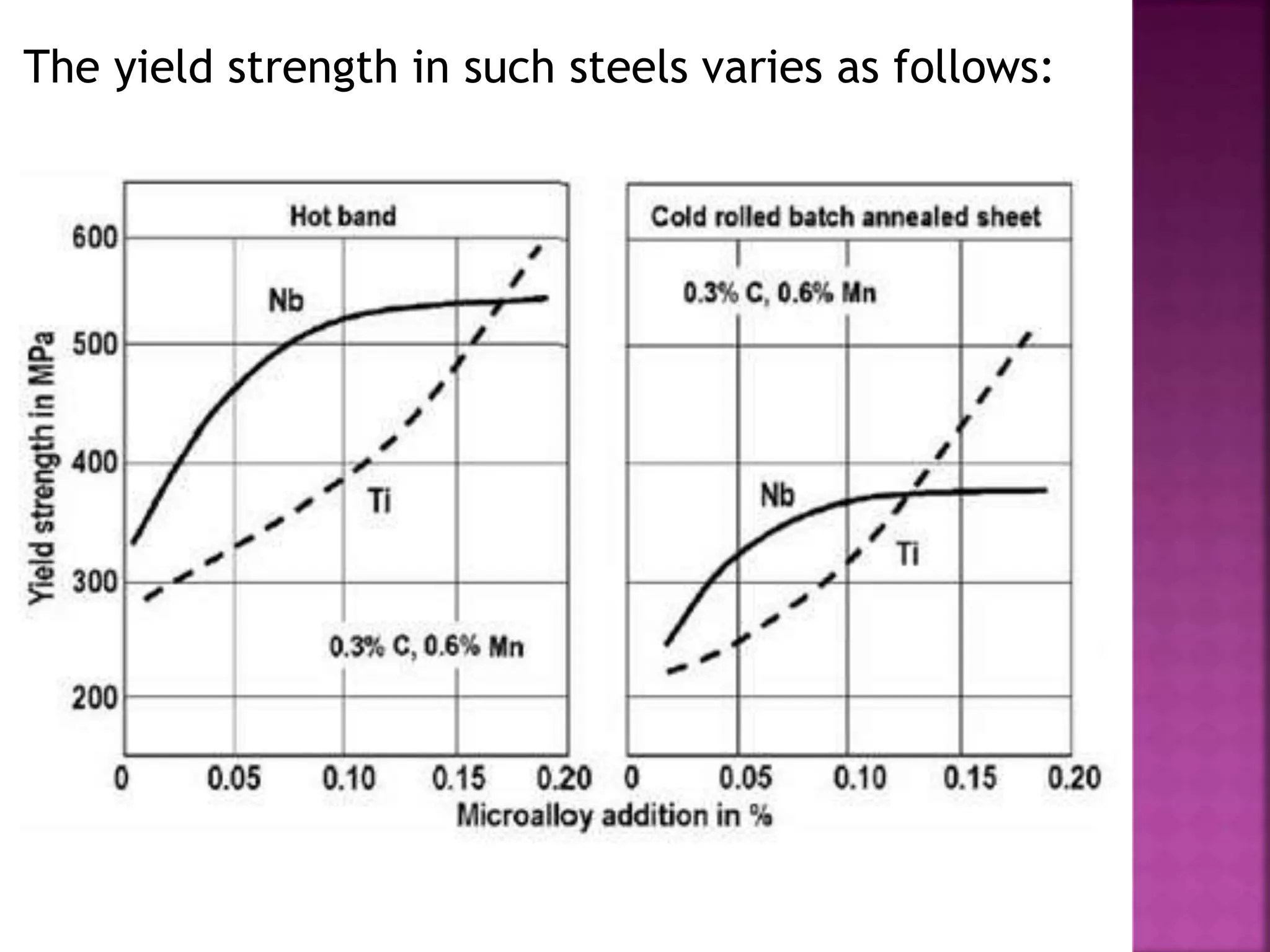

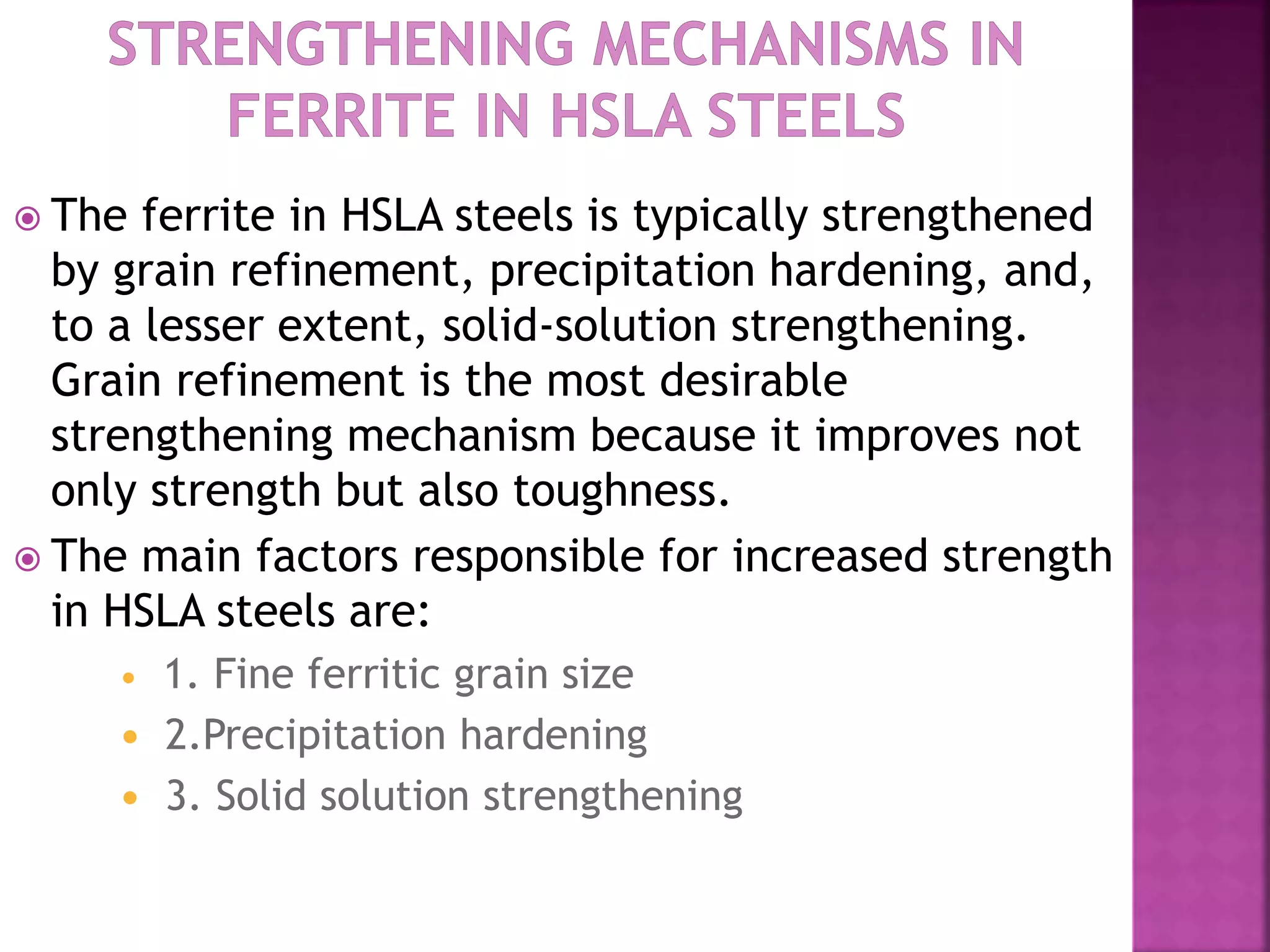

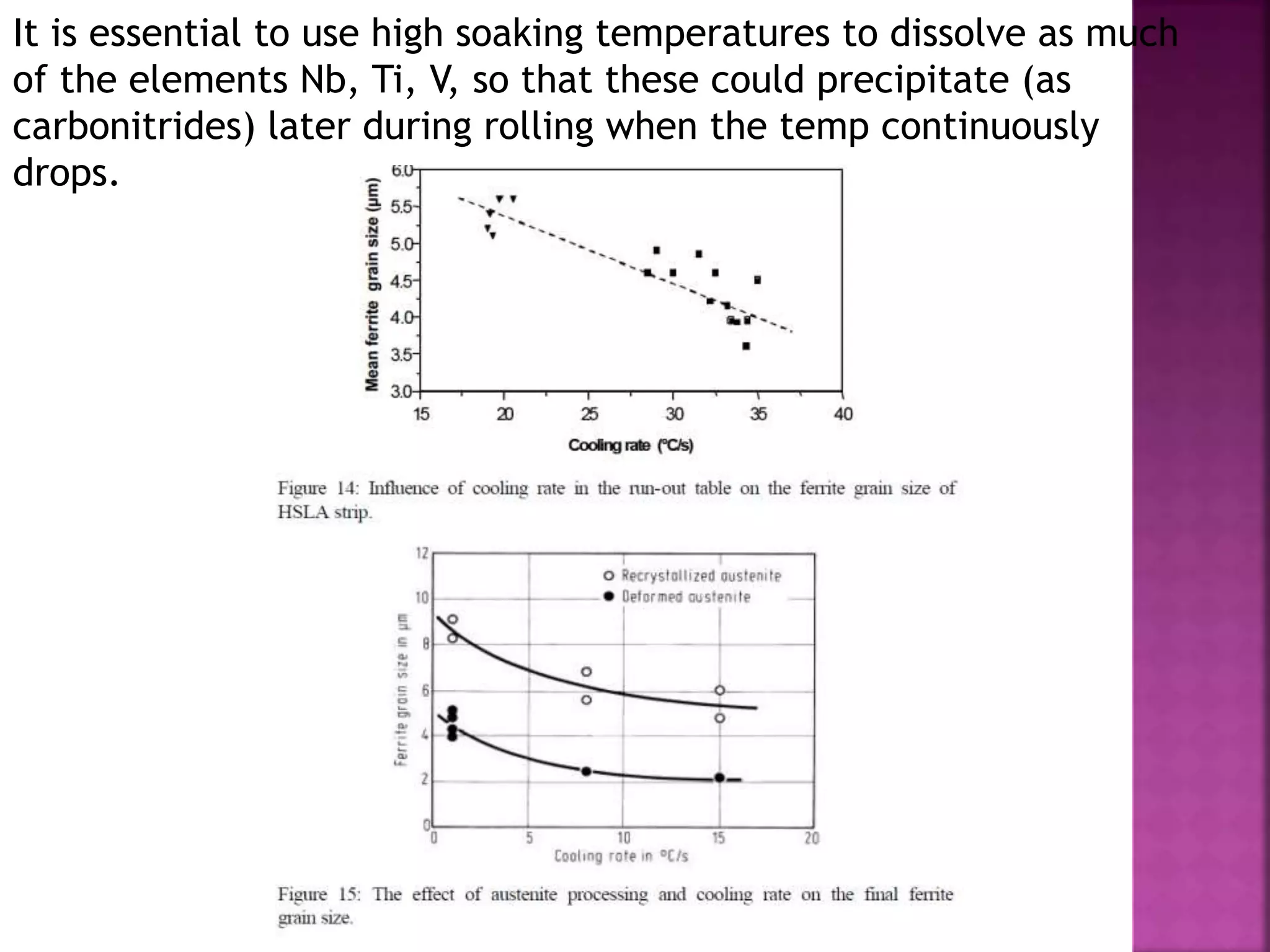

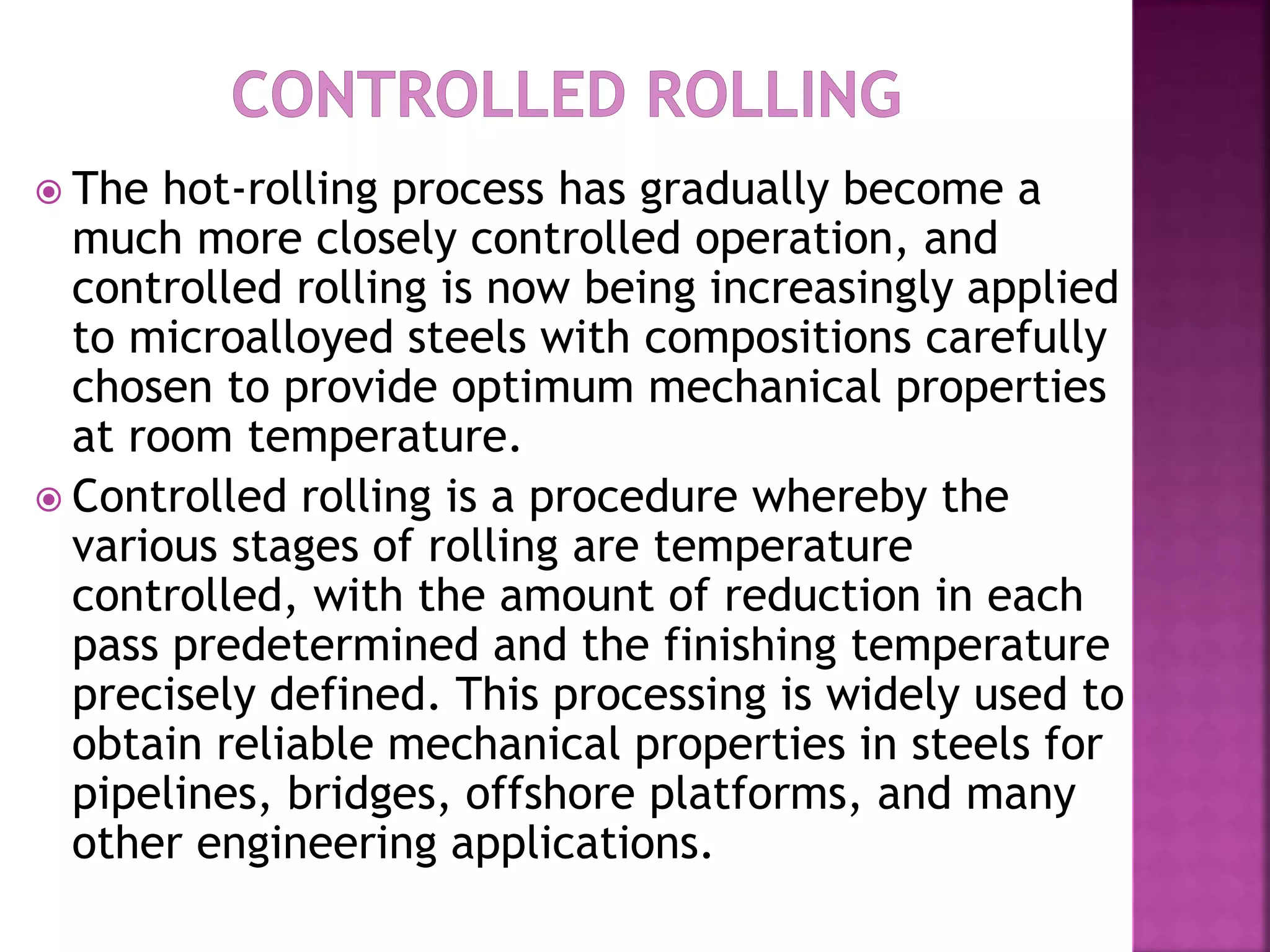

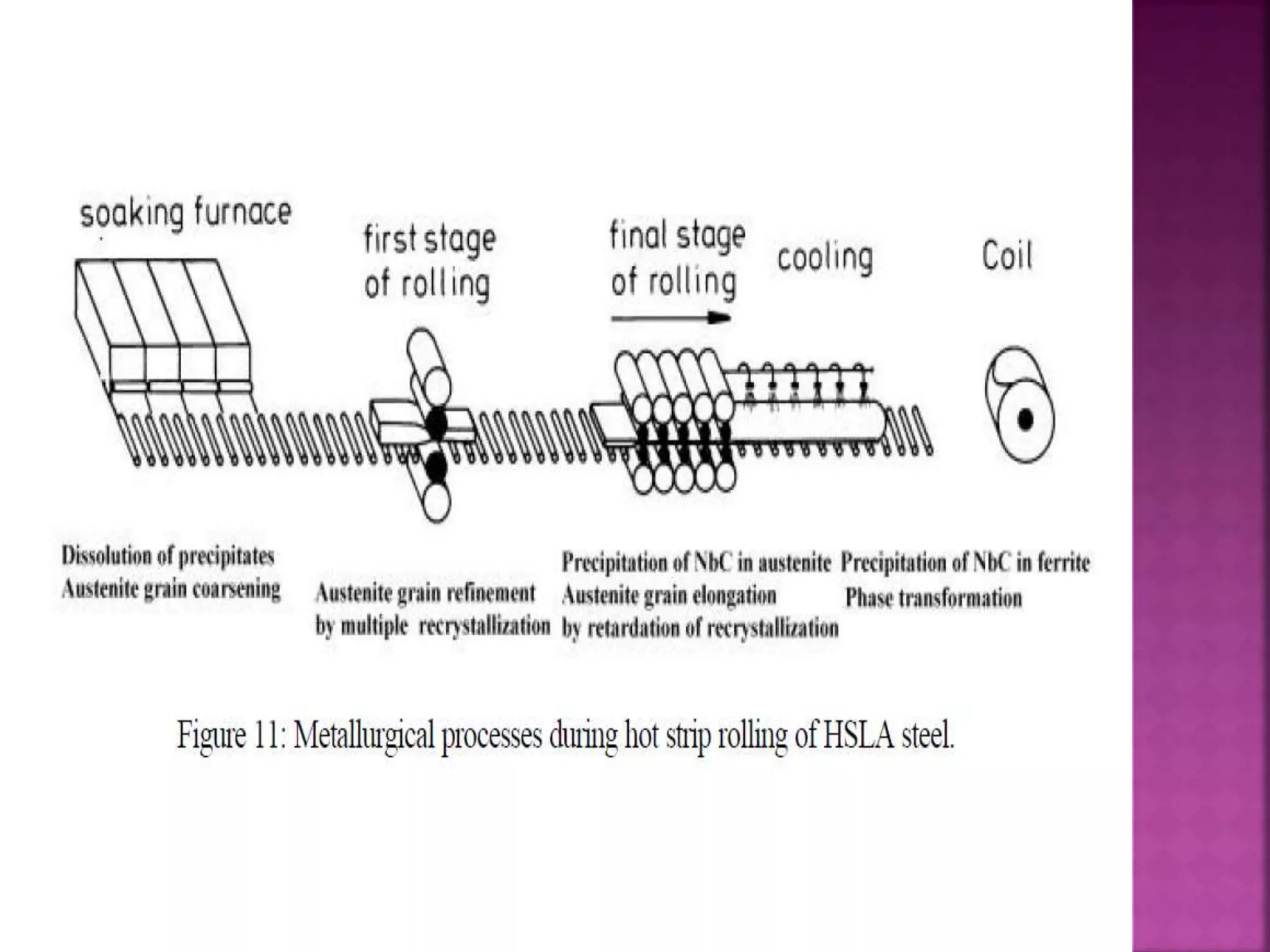

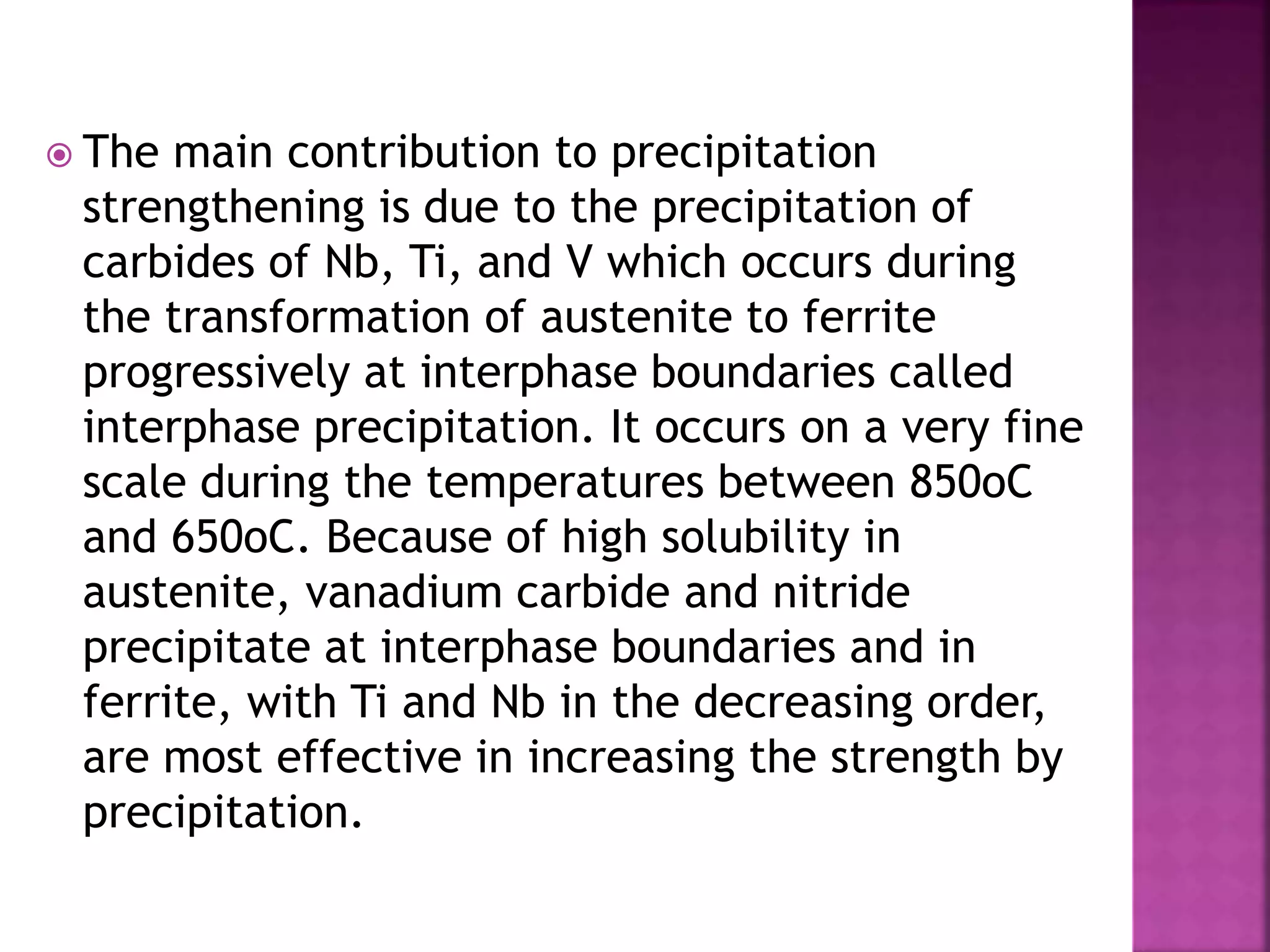

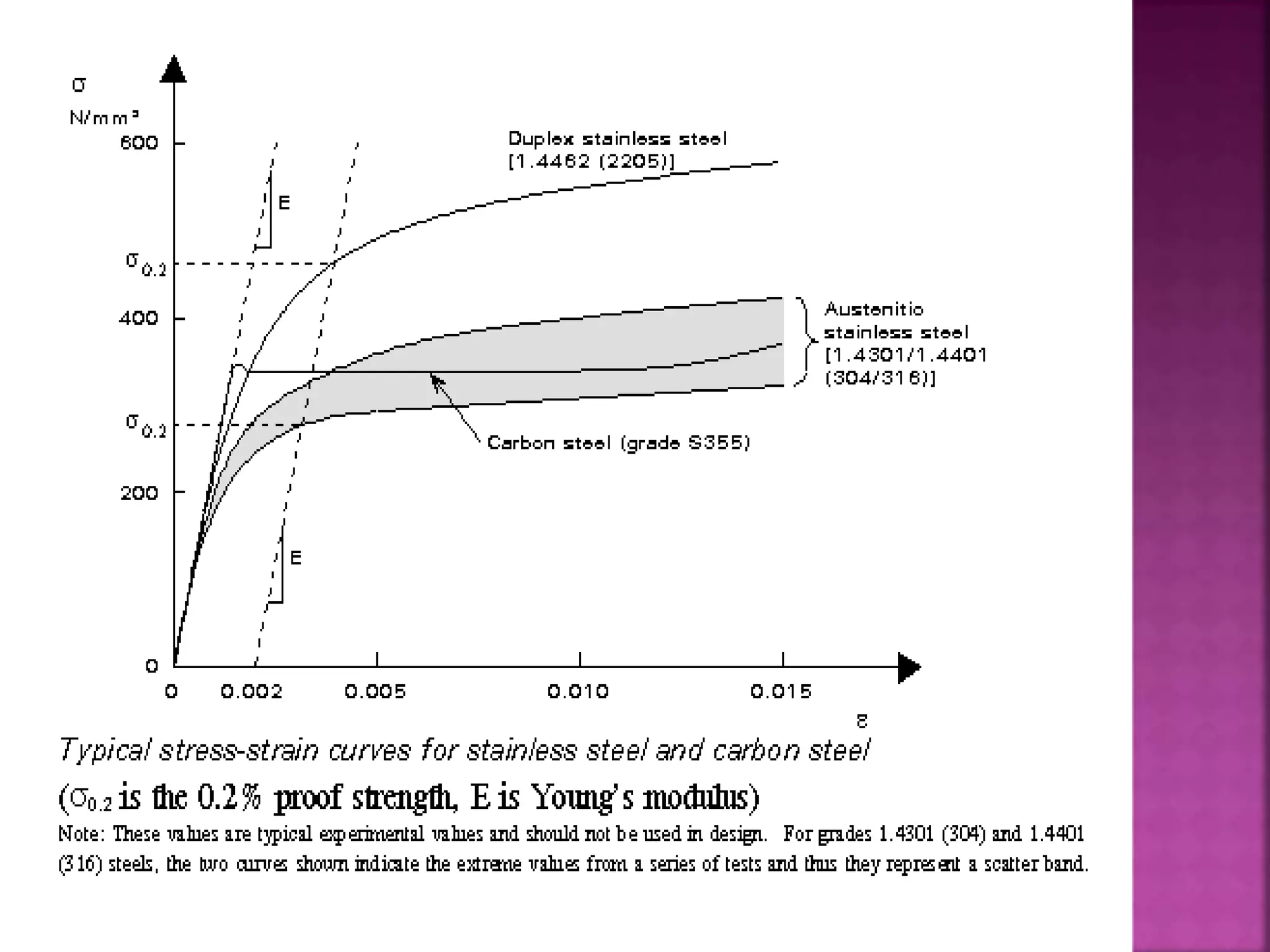

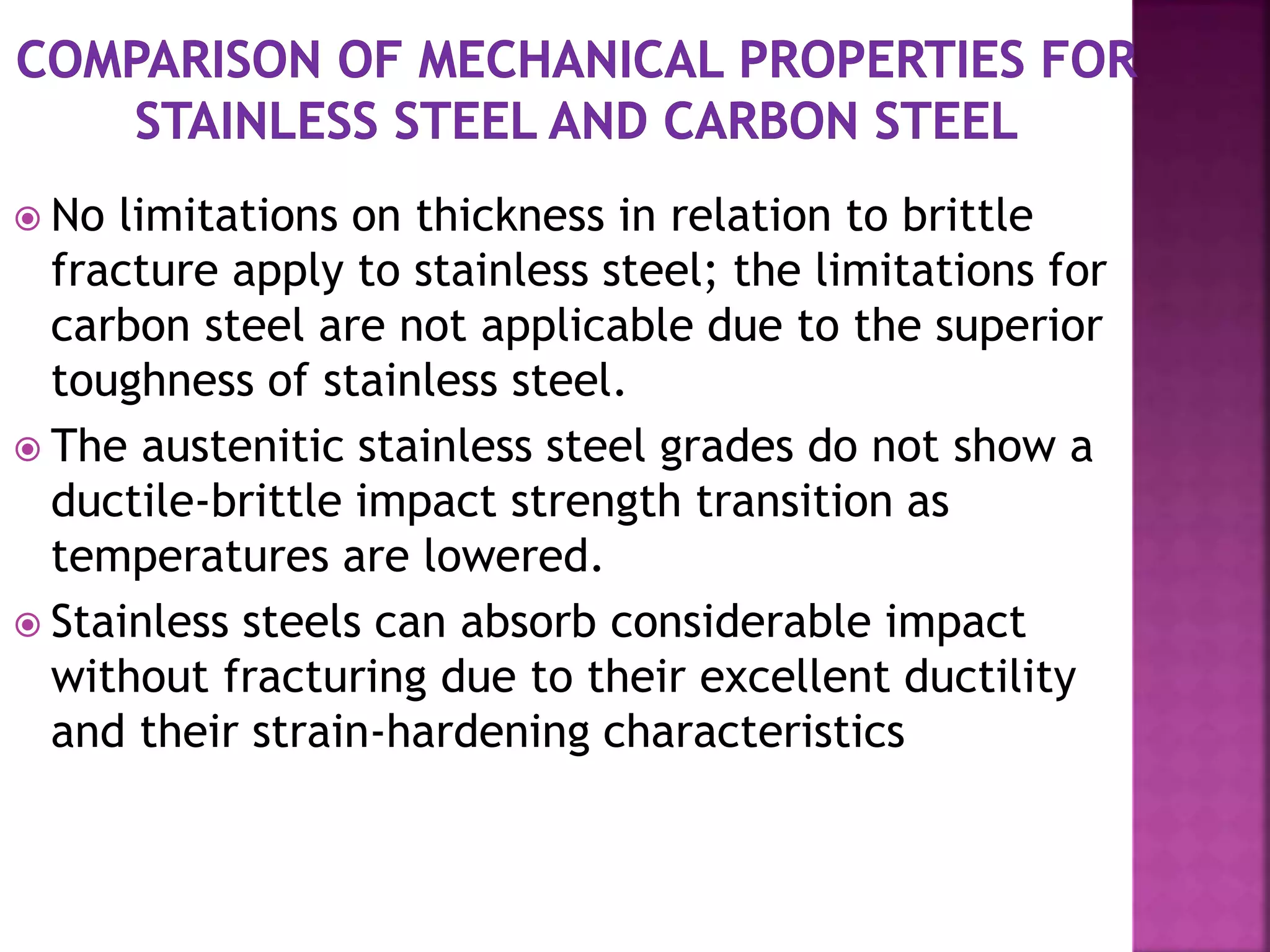

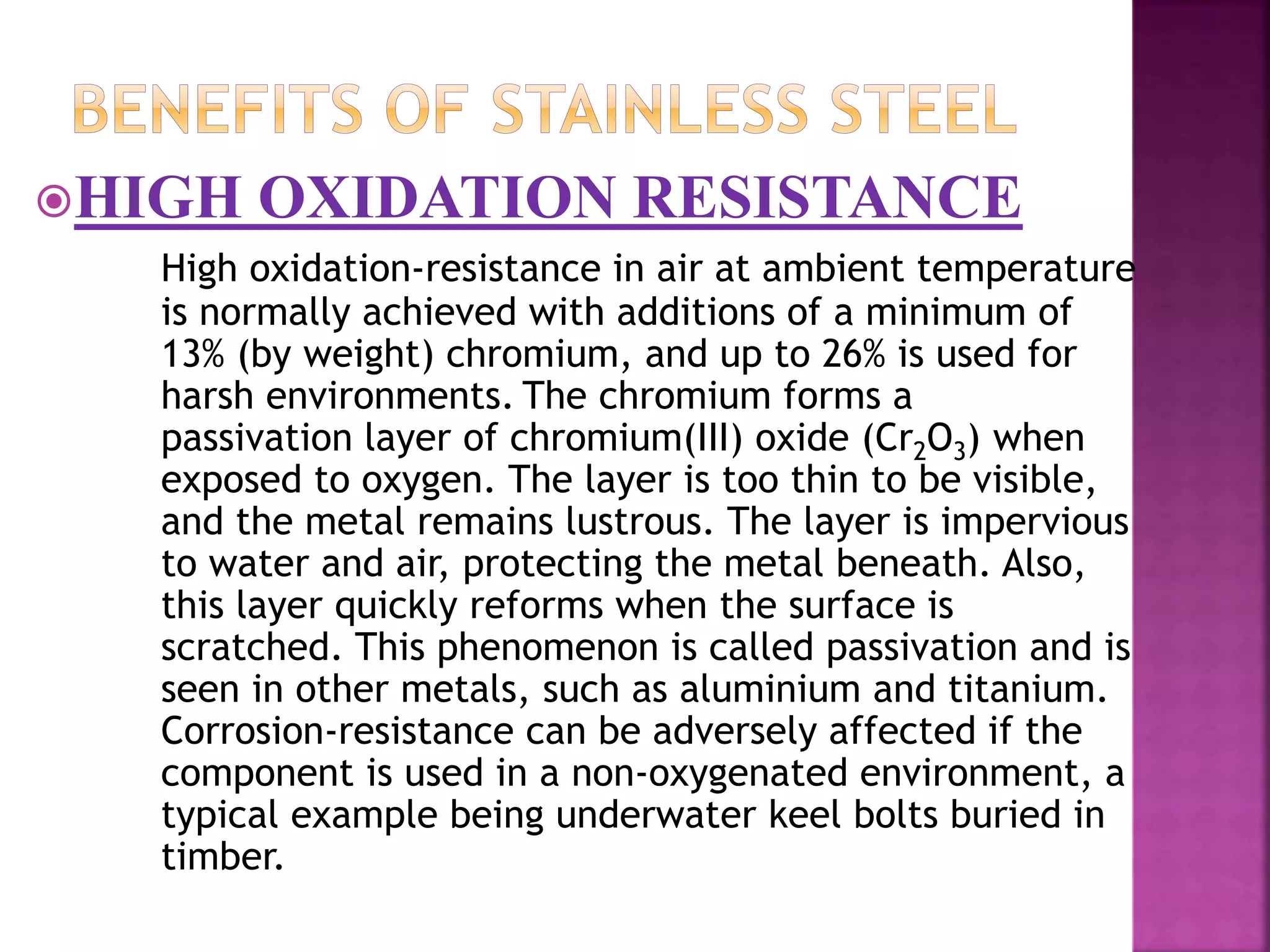

The document discusses the characteristics and classifications of carbon and alloy steels, focusing on their carbon content and alloying elements that influence strength, ductility, and hardenability. It covers low, medium, and high-carbon steels, detailing their applications and properties, as well as the specific roles of various alloying elements like manganese, chromium, and nickel in modifying steel properties. Additionally, it outlines the different types and uses of tool steels, emphasizing their heat treatment processes and the importance of their microstructure in performance.

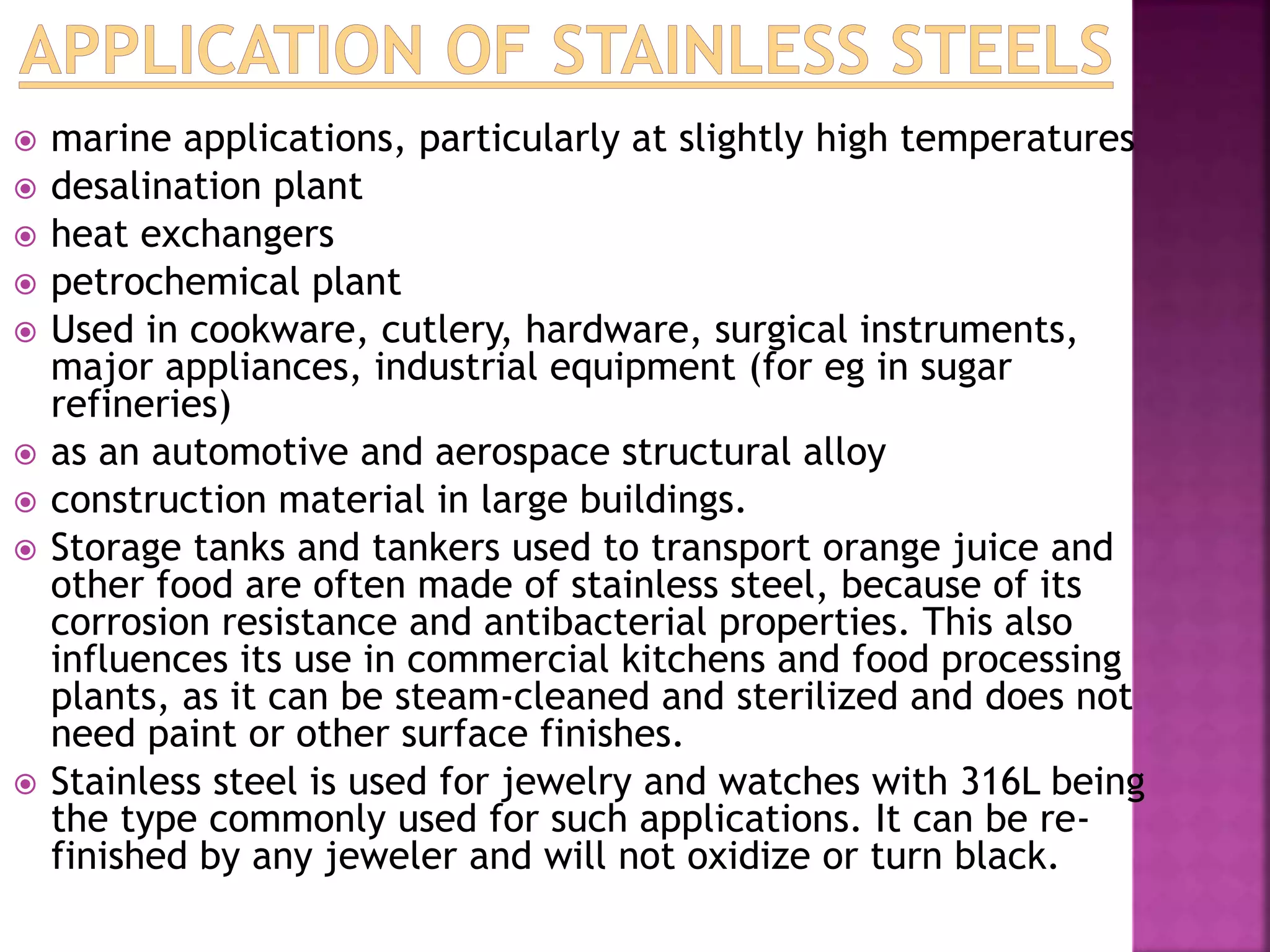

![The pinnacle of New York's

Chrysler Building is clad with

type 302 stainless steel.[13]

The arch rises from the bottom

left of the picture and is shown

against a featureless clear sky

The 630-foot (192 m) high,

stainless-clad (type 304)

Gateway Arch defines St. Louis's

skyline.](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/typesofsteelsheat-170225190039/75/Types-of-steels-in-use-139-2048.jpg)