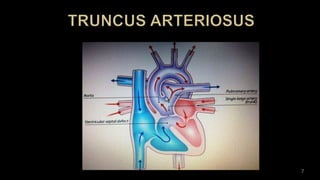

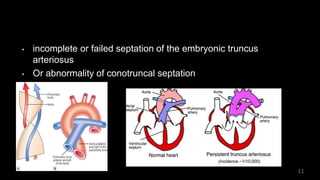

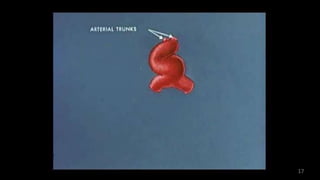

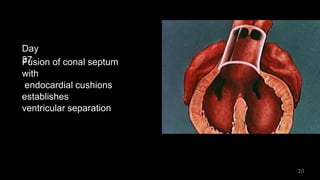

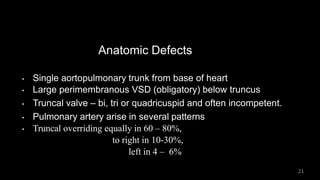

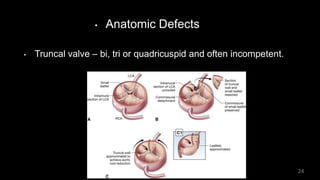

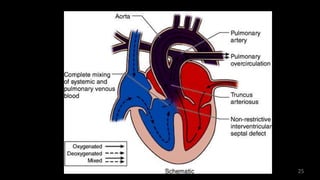

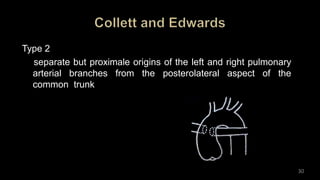

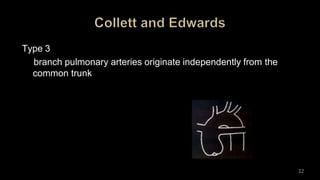

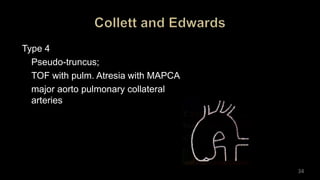

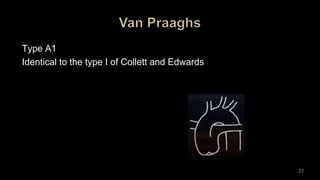

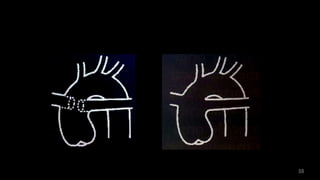

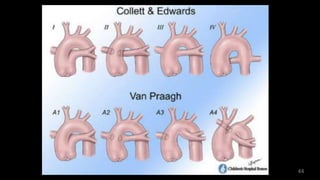

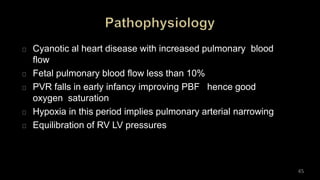

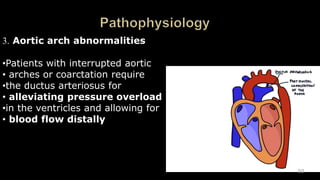

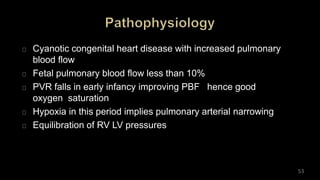

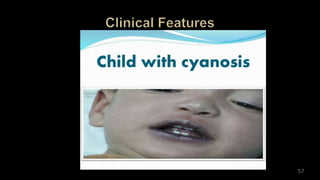

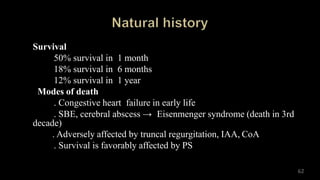

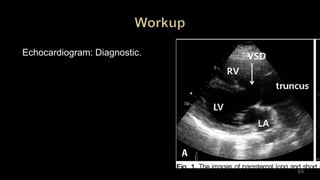

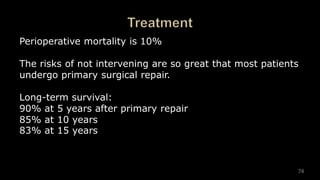

Dr. Walinjom Joshua presented on persistent truncus arteriosus, a congenital heart defect where a single arterial trunk arises from the heart, supplying the systemic circulation, pulmonary circulation, and coronary arteries. The key features are a large ventricular septal defect below the arterial trunk and a commonly incompetent truncal valve with two to four leaflets. Patients typically present within the first two weeks of life with cyanosis and congestive heart failure. Diagnosis is made using echocardiography, chest x-ray and electrocardiogram. Surgical repair is usually performed within the first month of life to separate the pulmonary and systemic circulations.