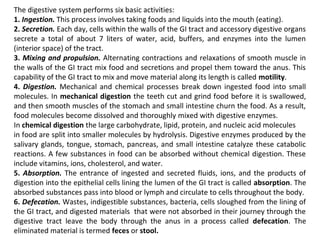

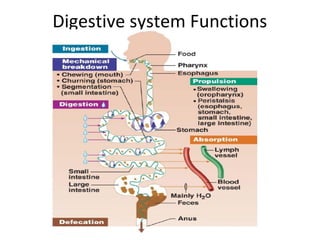

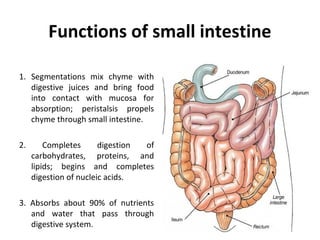

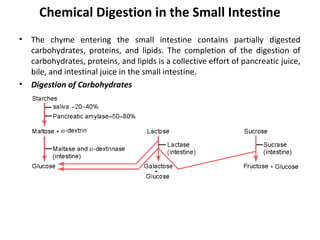

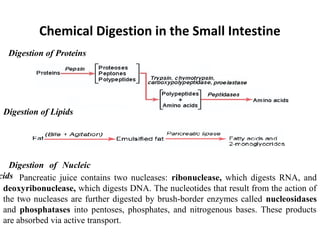

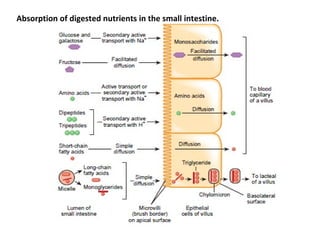

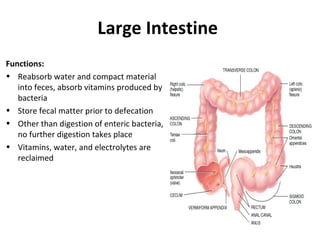

The digestive system performs six main functions: ingestion, secretion, mixing/propulsion, digestion, absorption, and defecation. The small intestine plays a key role in digestion and absorption. It completes the breakdown of carbohydrates, proteins and lipids through enzymes and absorbs over 90% of nutrients. Movements like segmentations and migrating motility complexes mix contents to bring them in contact with the intestinal wall for absorption and propel digestion forward.