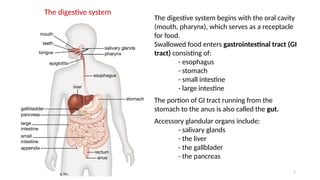

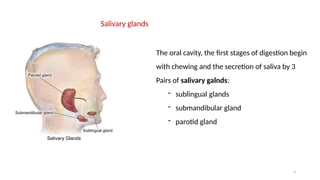

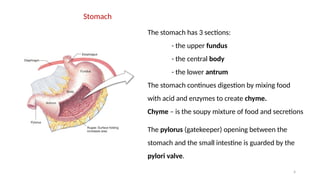

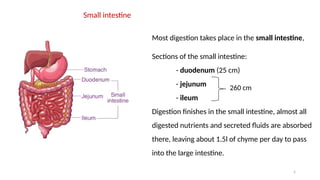

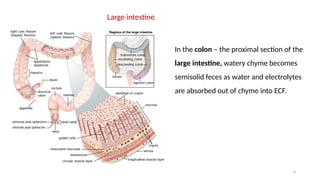

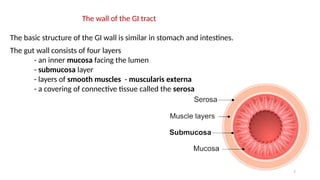

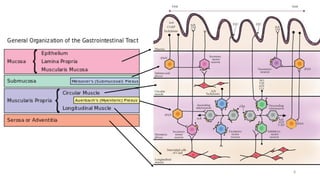

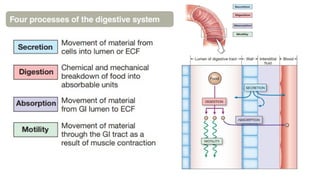

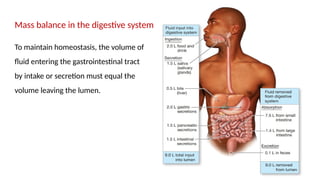

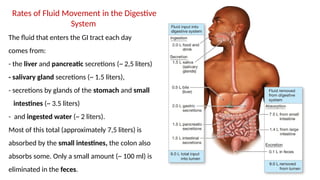

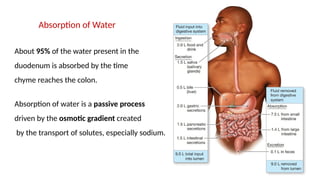

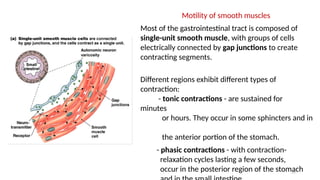

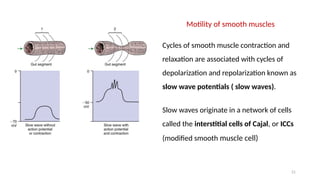

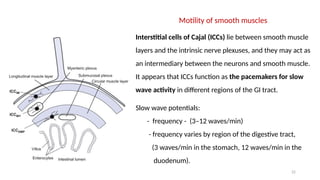

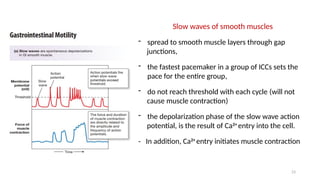

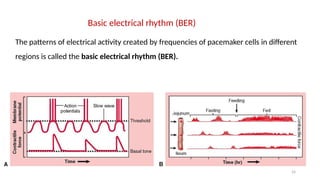

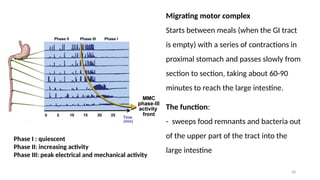

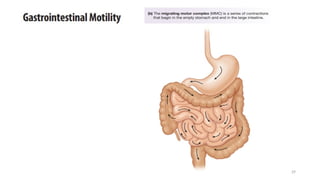

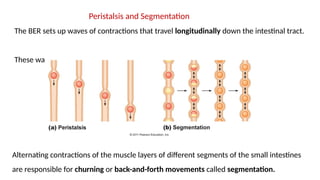

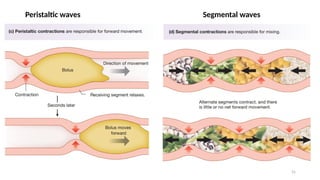

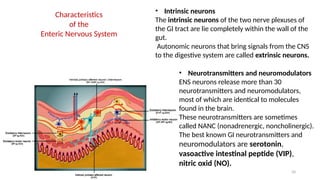

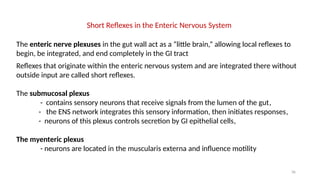

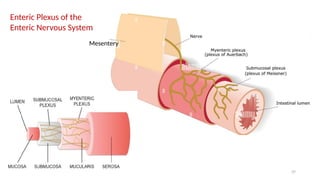

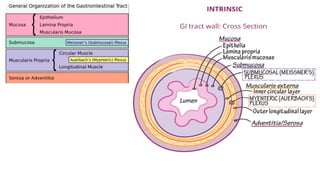

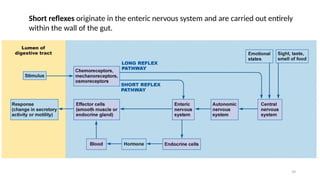

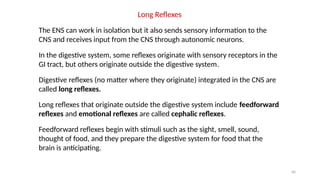

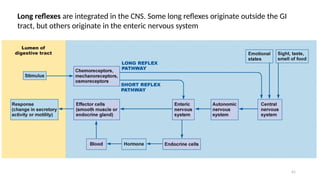

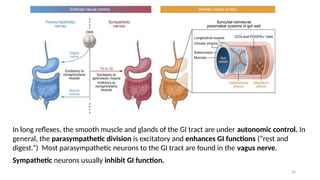

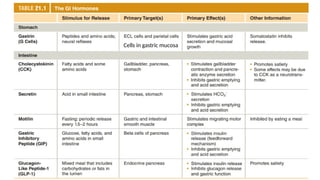

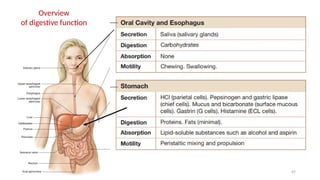

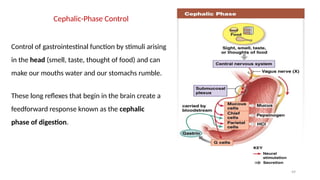

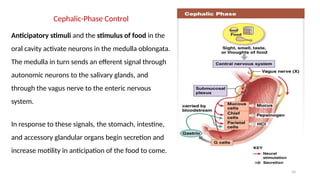

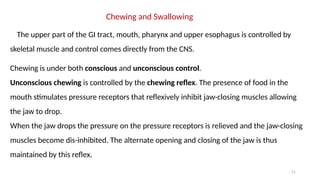

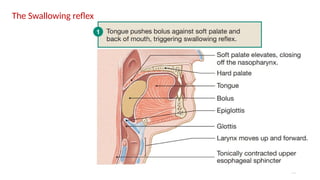

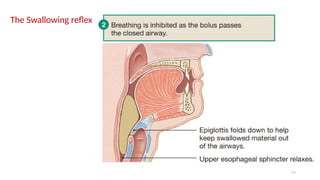

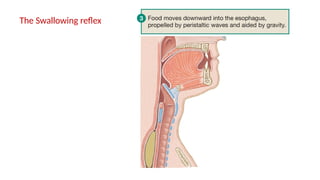

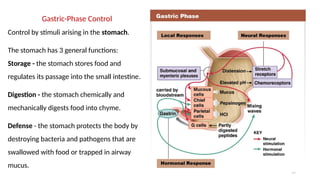

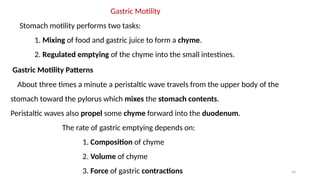

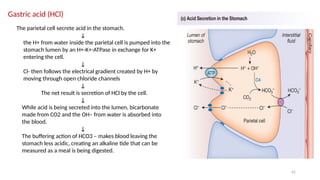

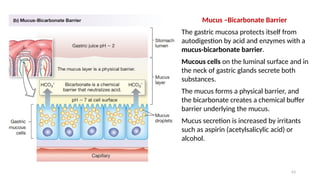

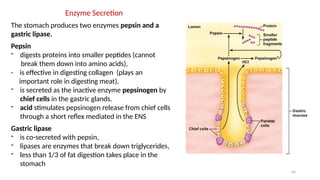

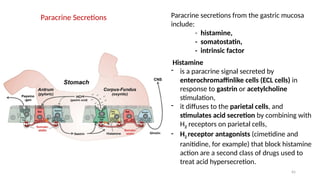

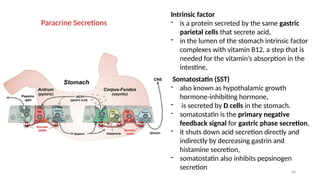

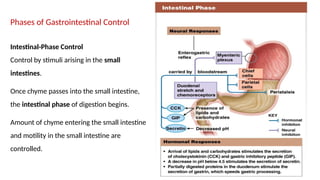

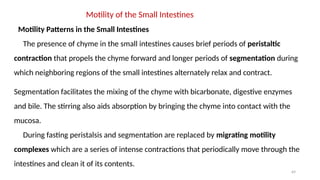

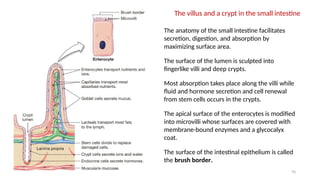

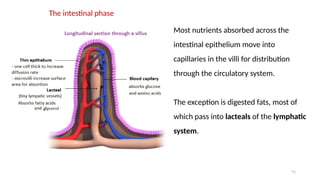

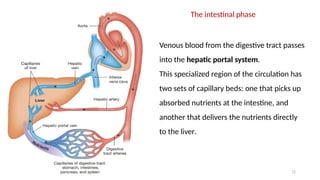

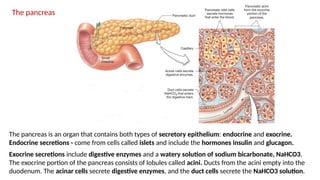

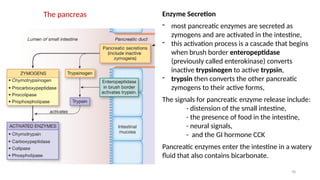

The document provides an overview of the digestive system, detailing its structure, including the gastrointestinal tract and accessory organs, and the processes that occur at each stage of digestion. It explains the roles of various enzymes, hormones, and motility patterns that facilitate digestion and absorption, as well as the regulation of these processes by the enteric nervous system. Additionally, it highlights the importance of fluid balance, defense mechanisms, and the phases of gastrointestinal control in regulating digestive functions.