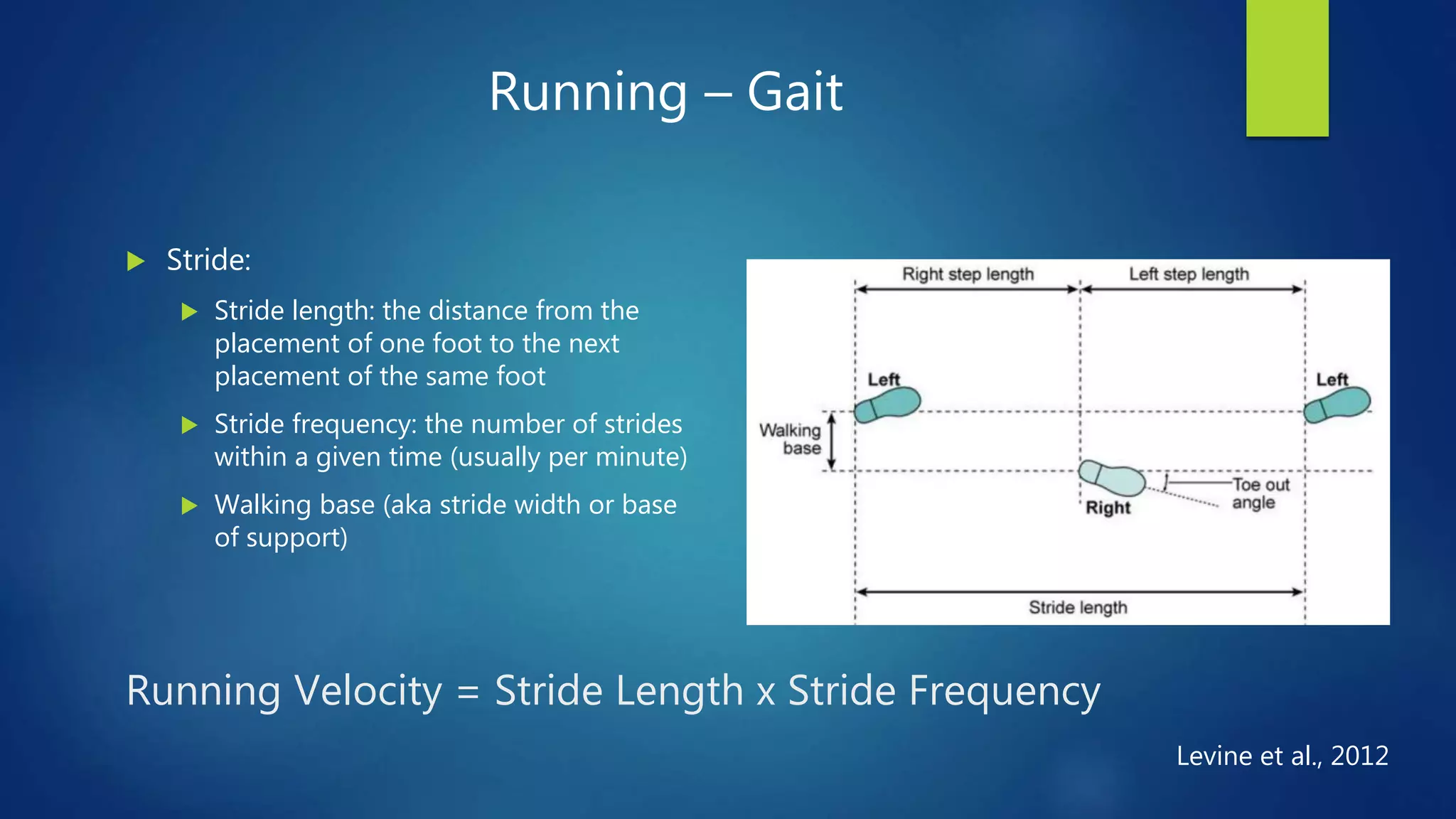

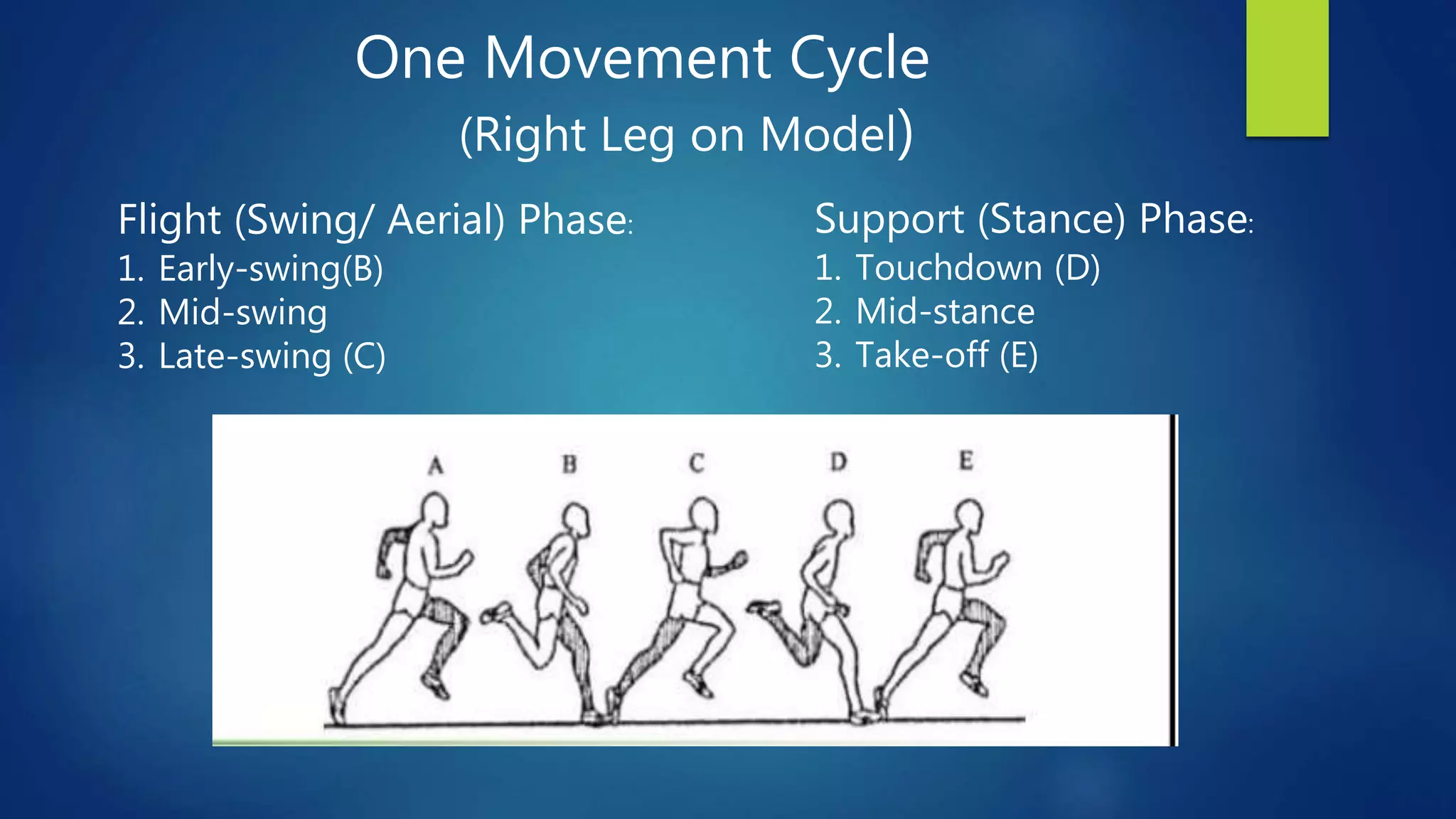

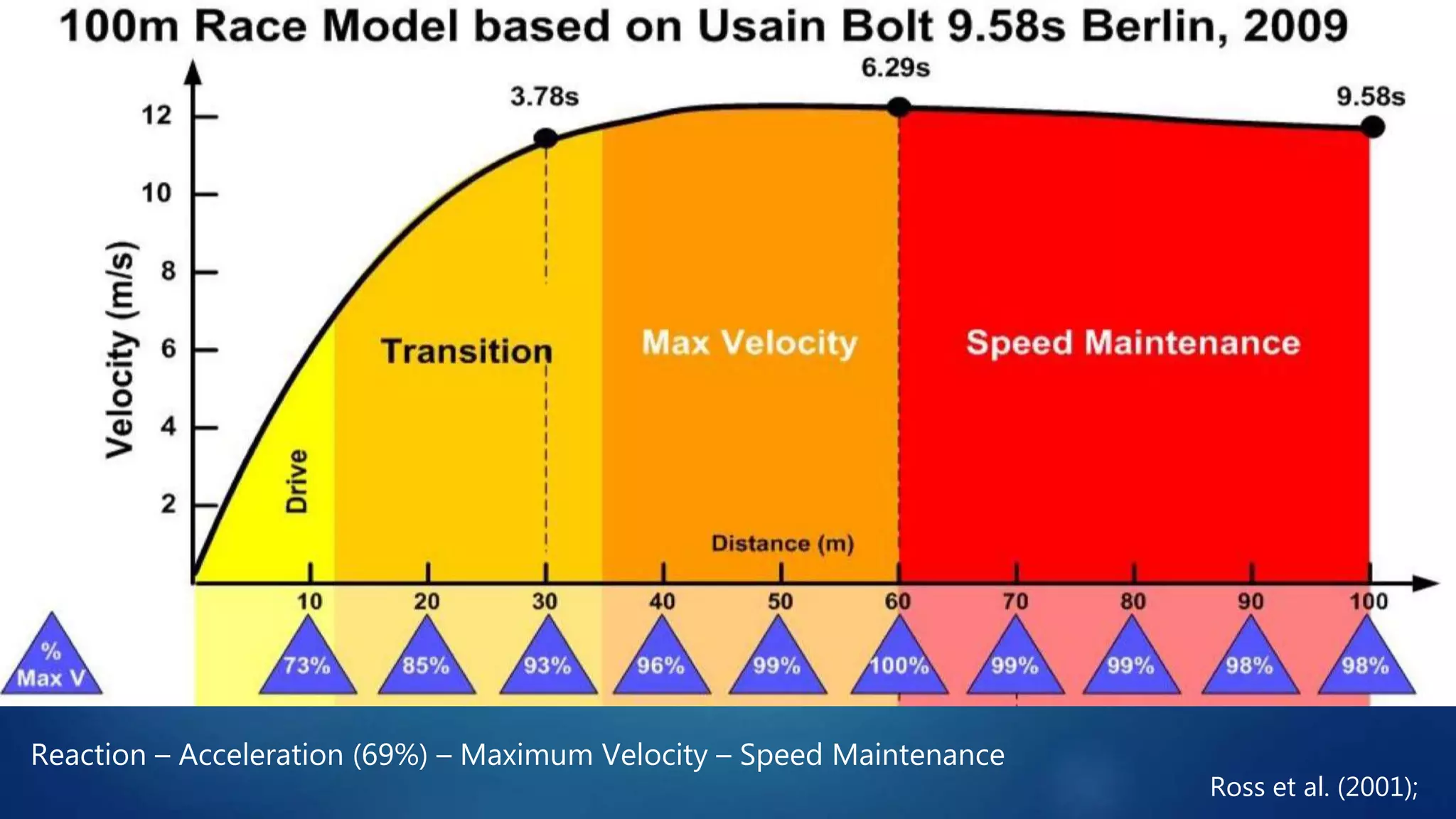

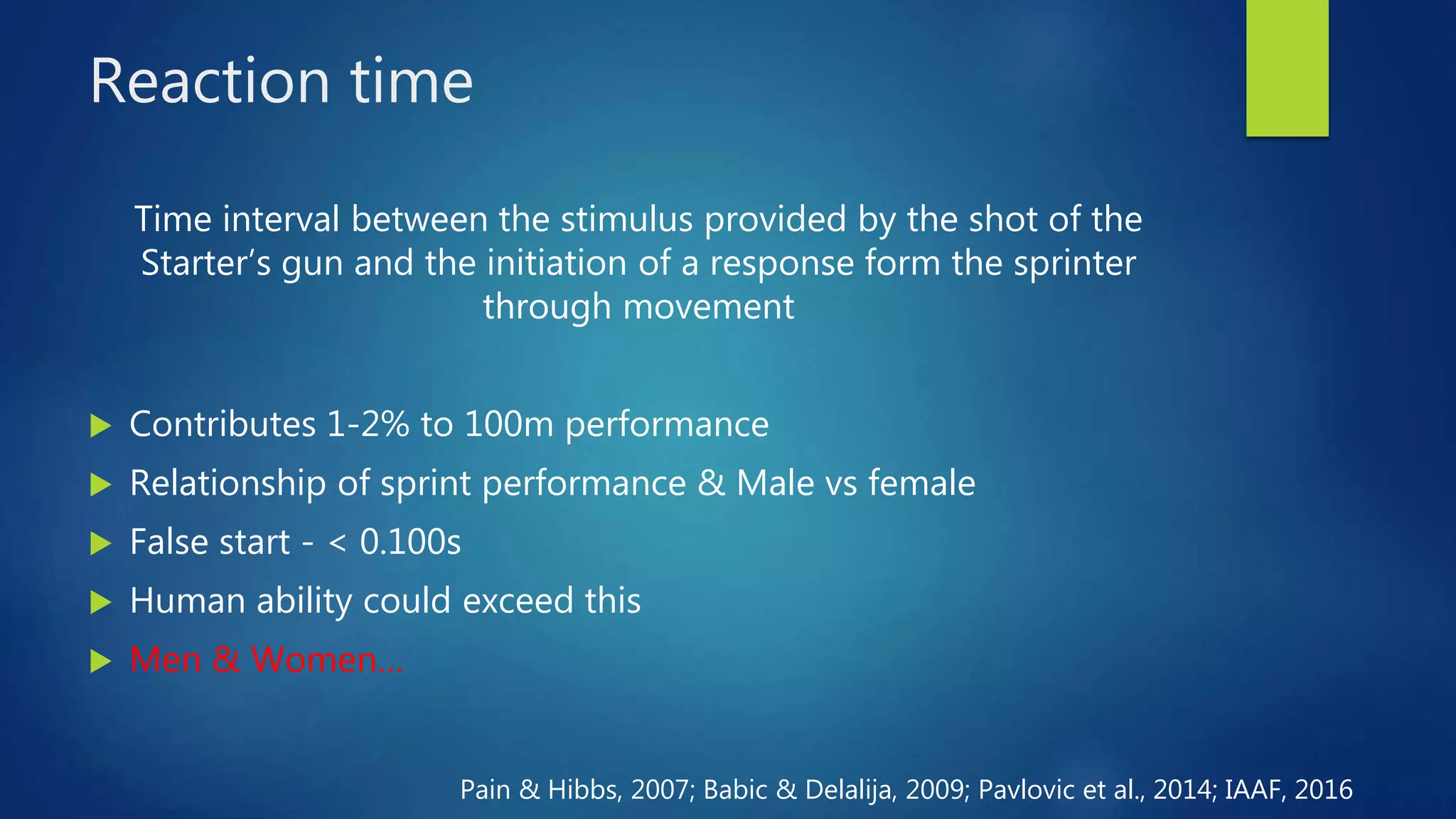

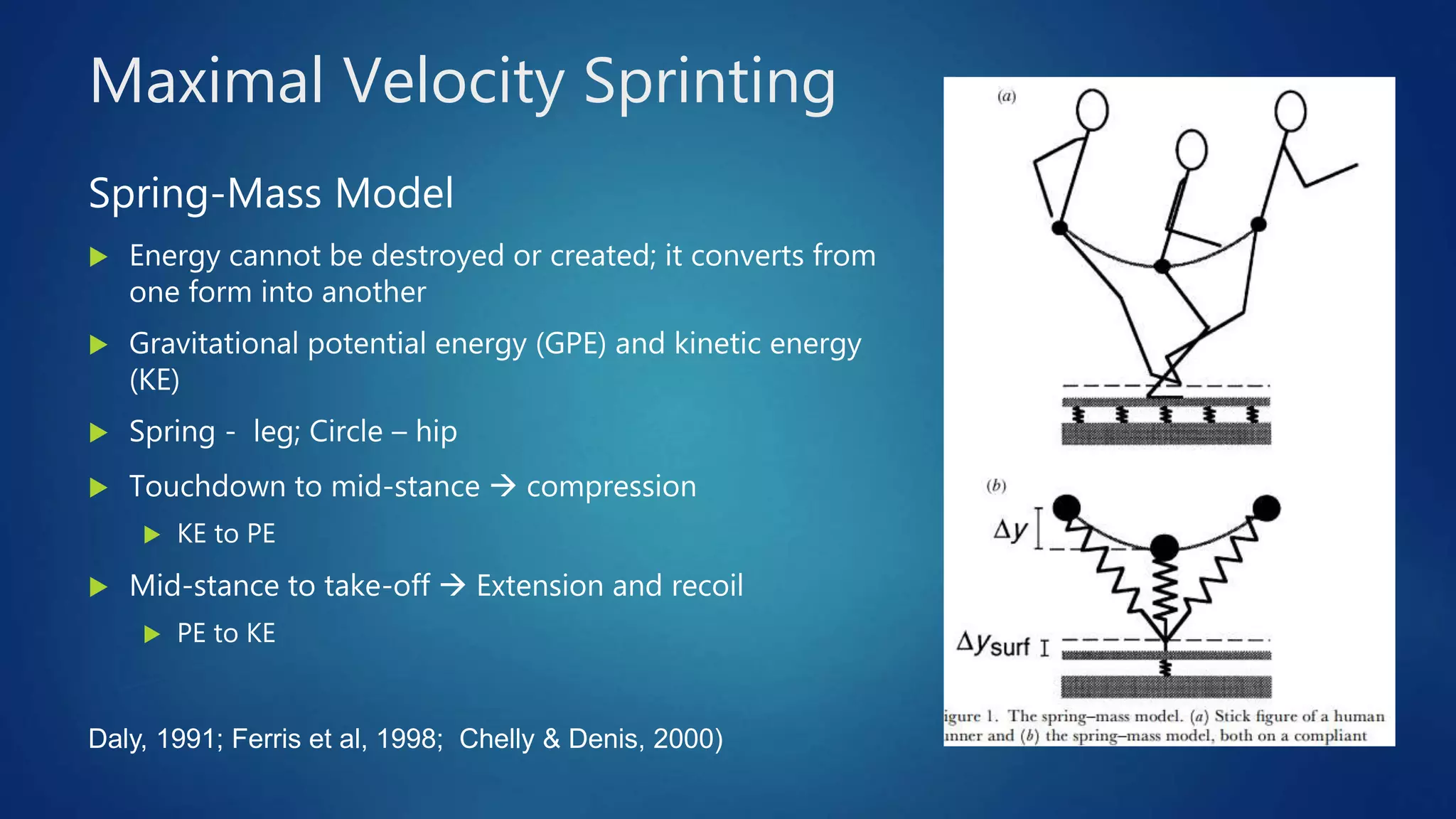

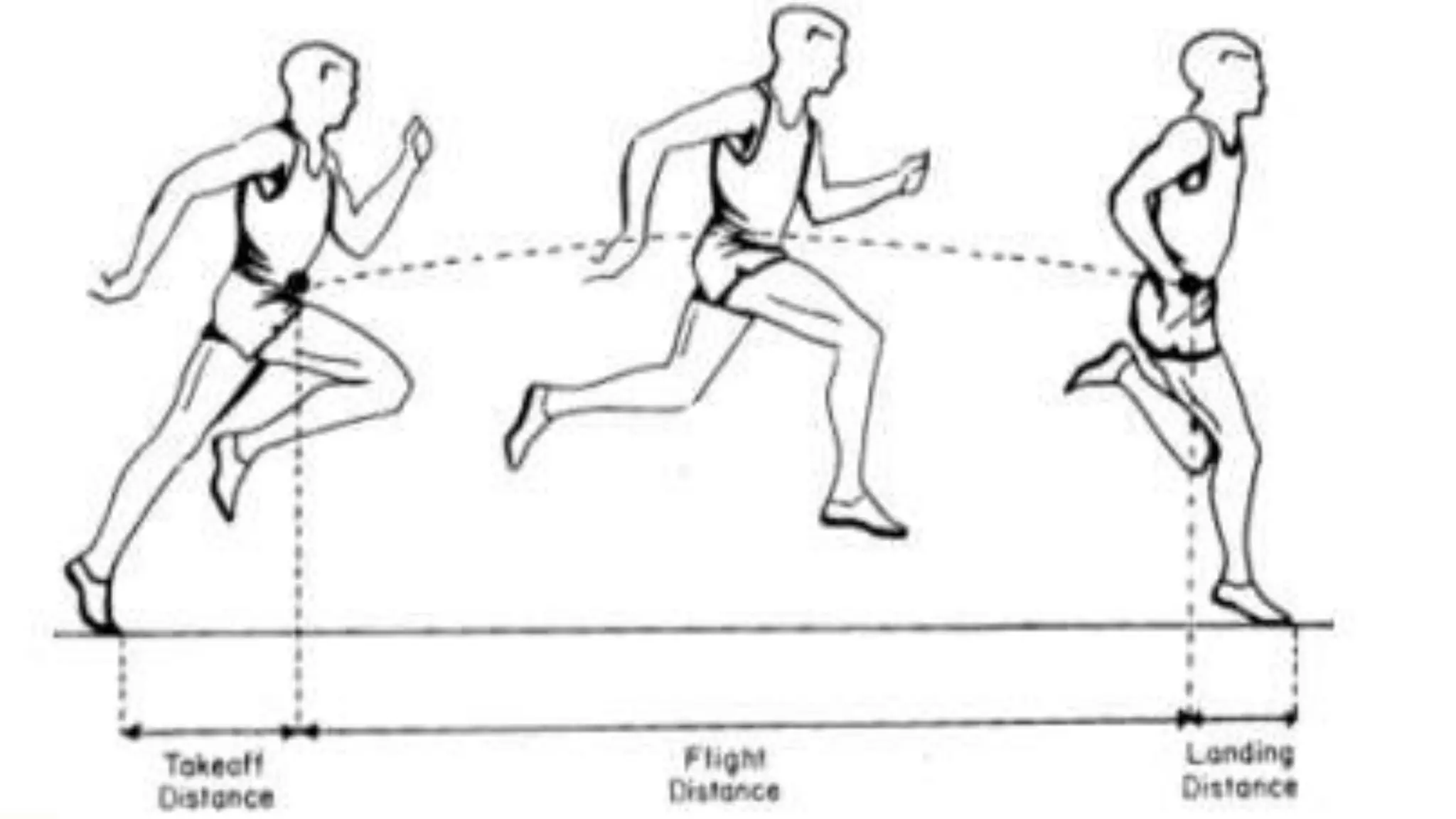

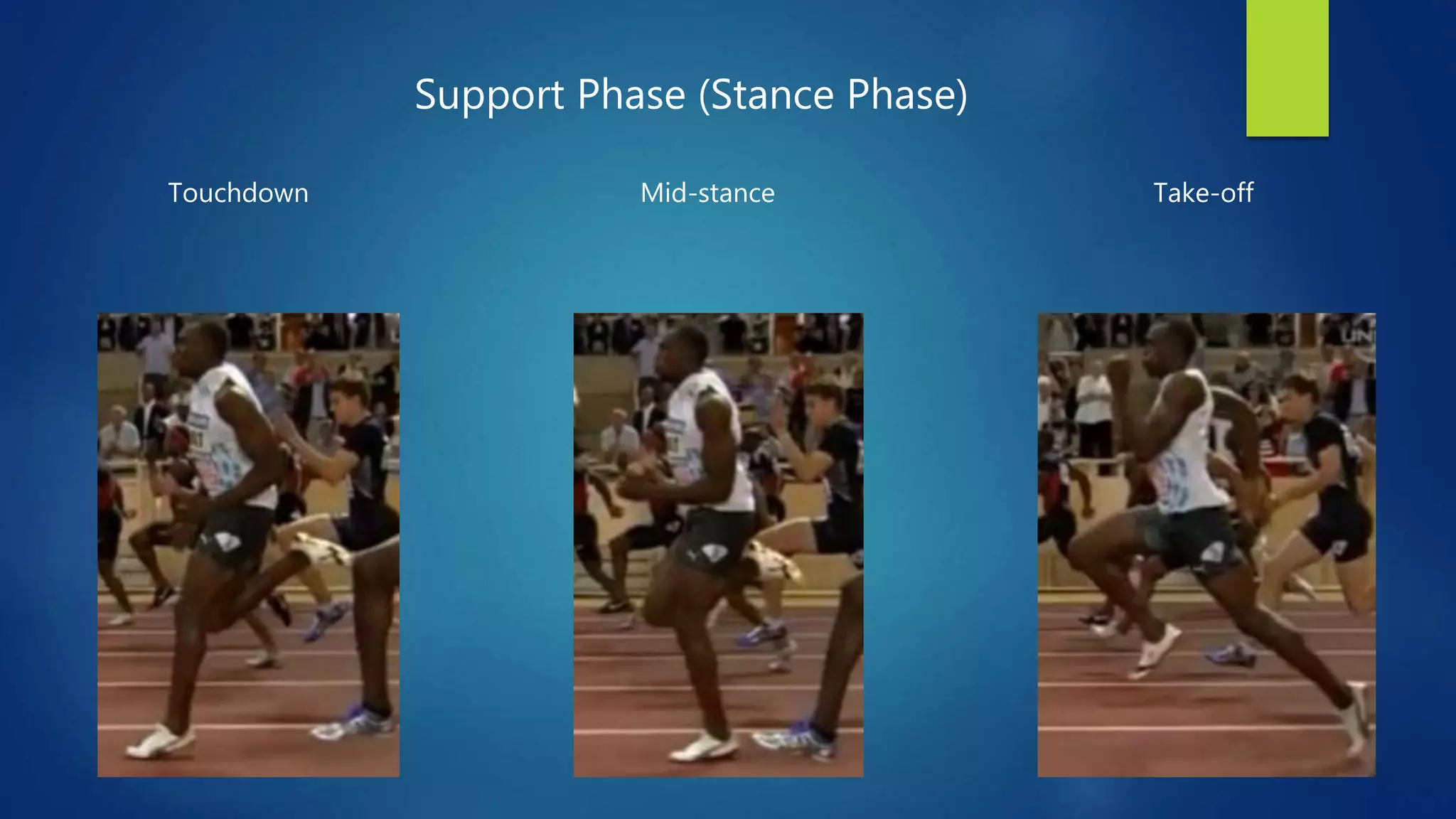

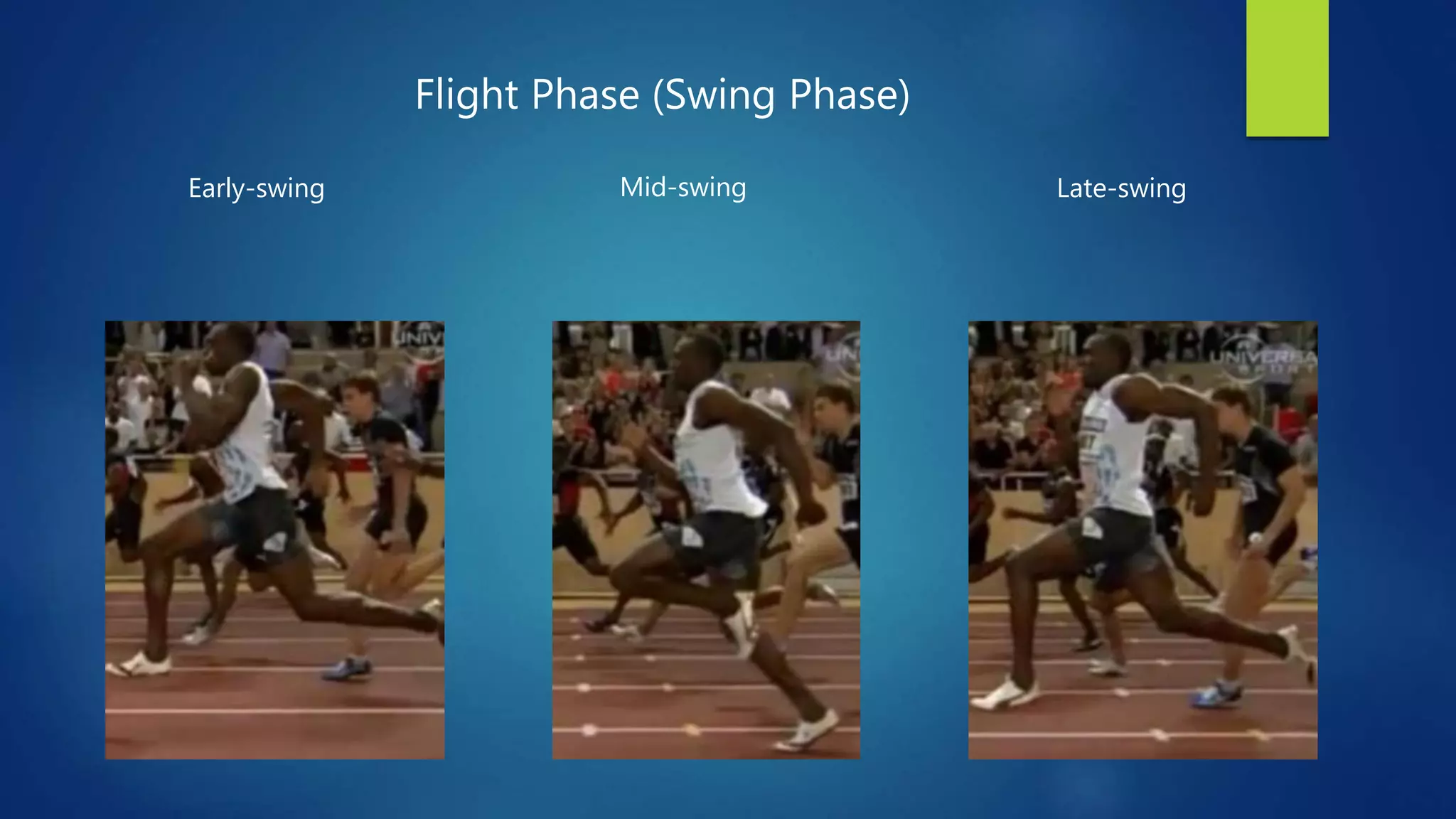

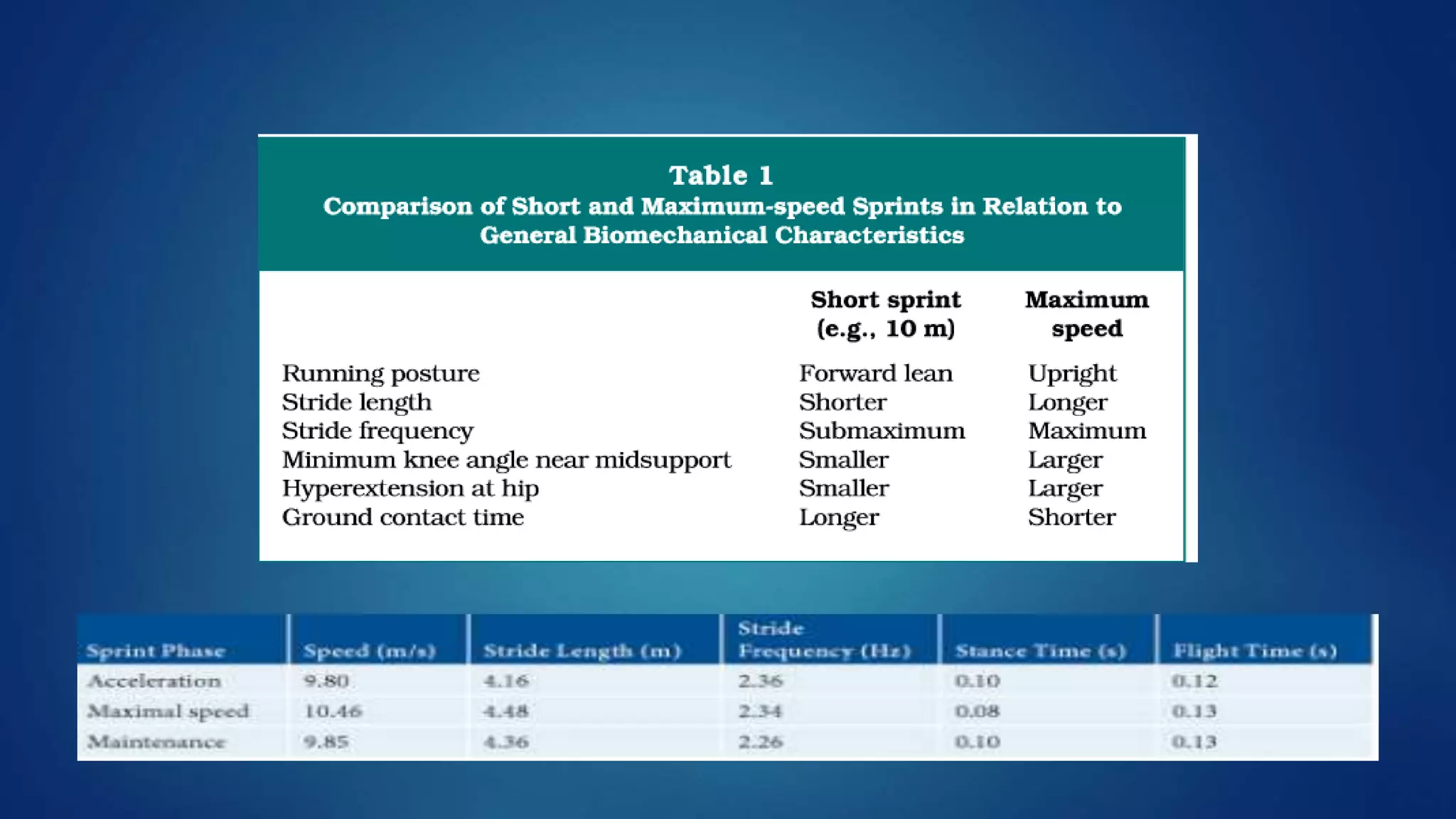

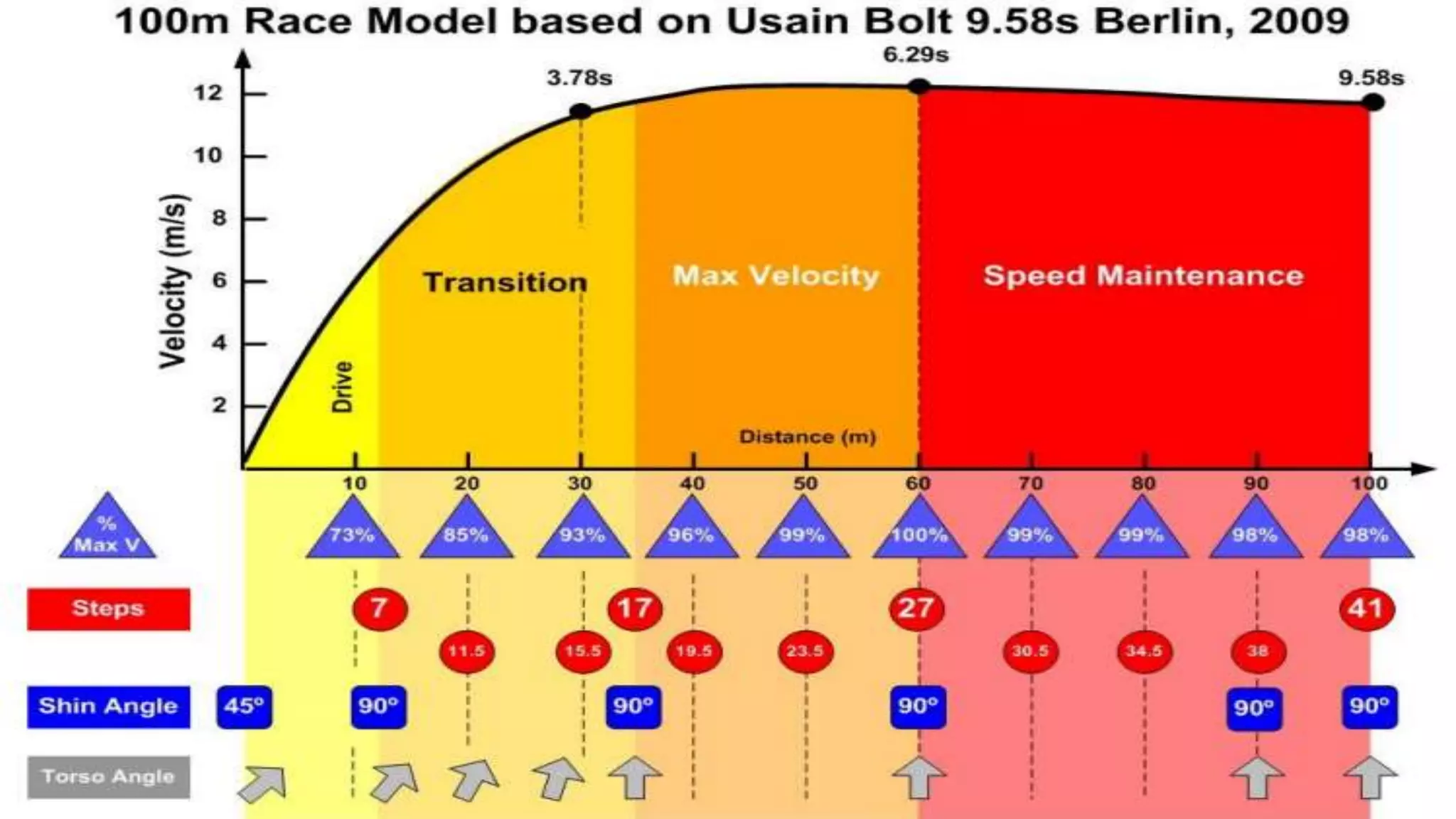

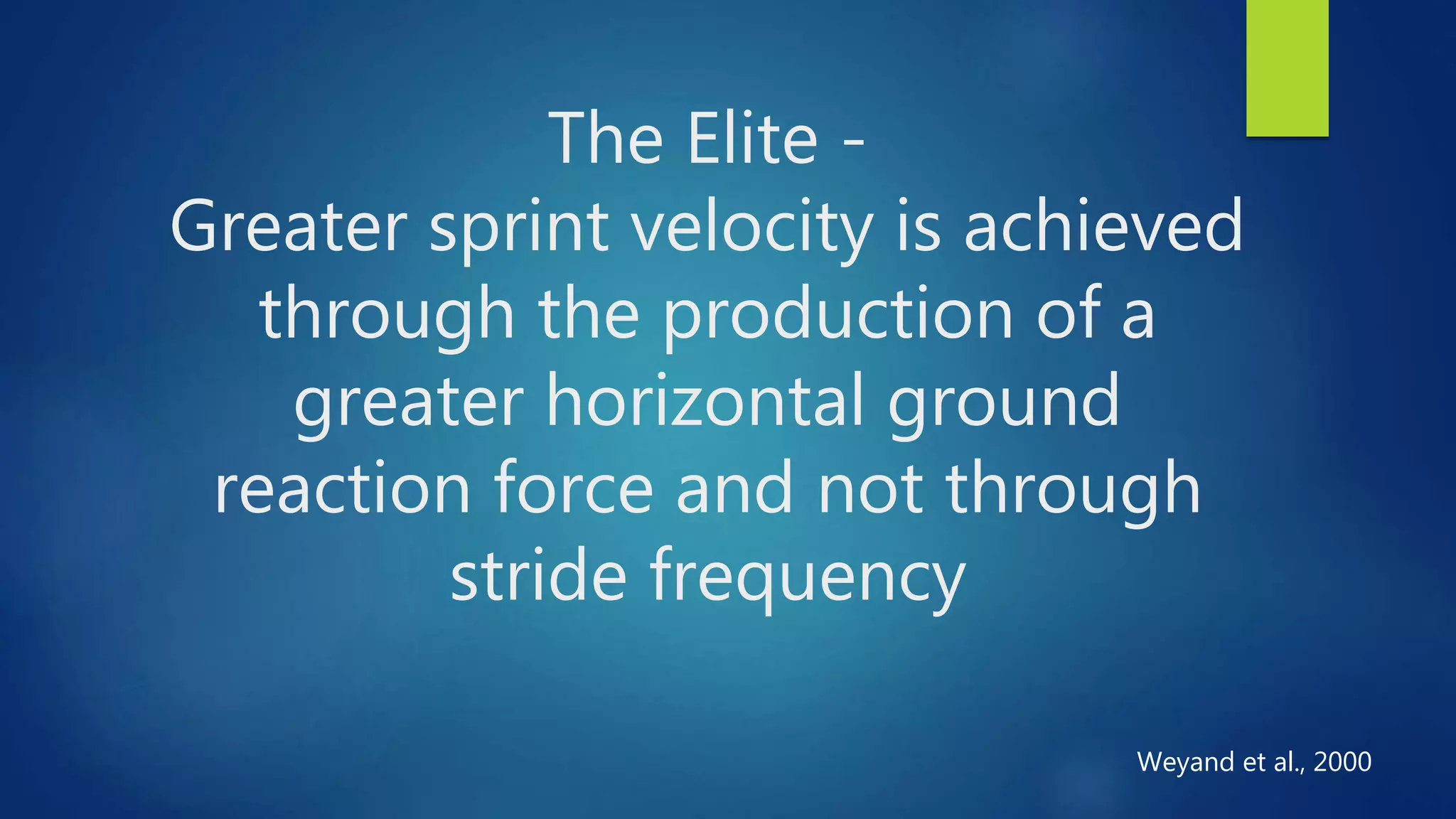

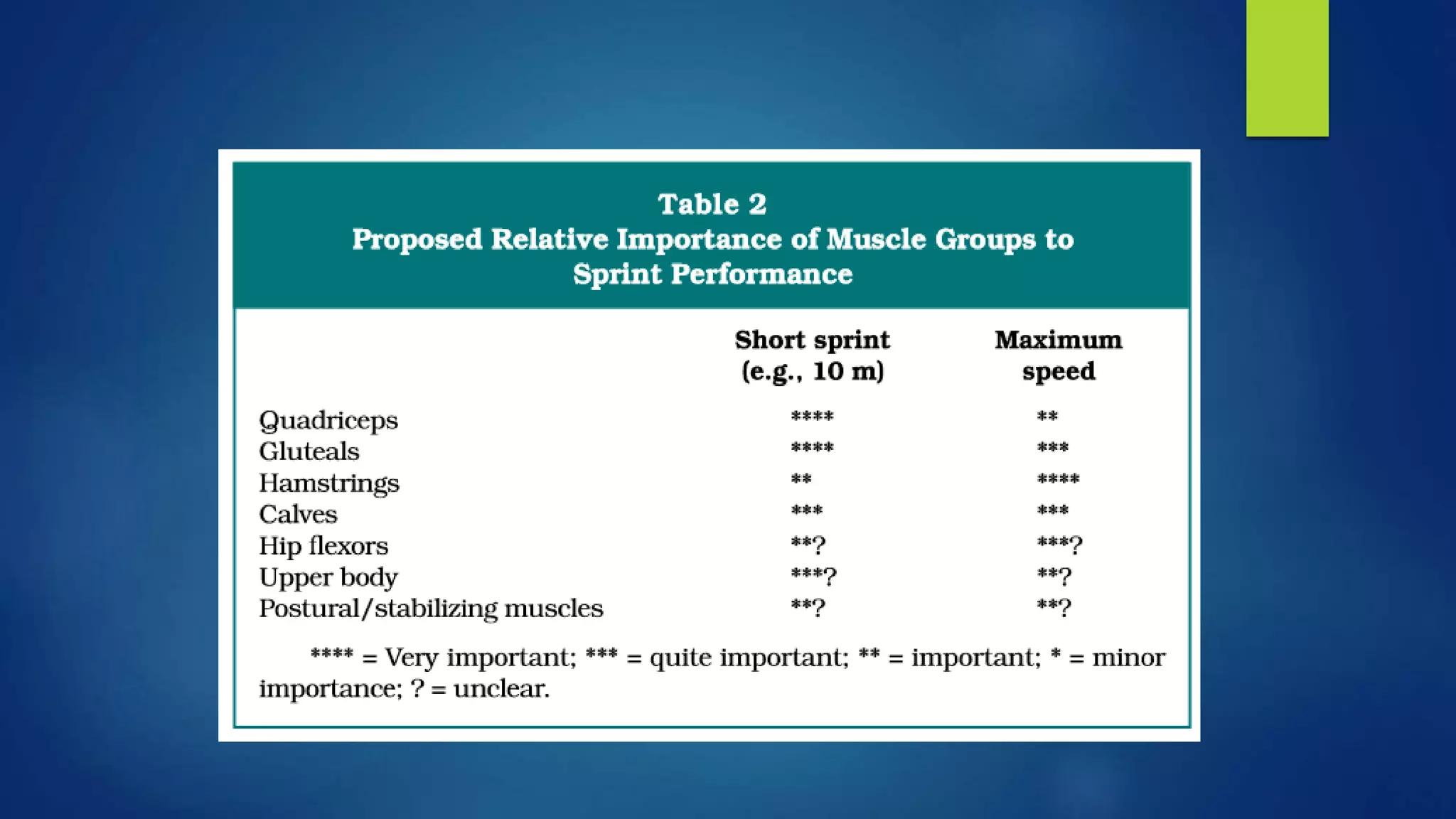

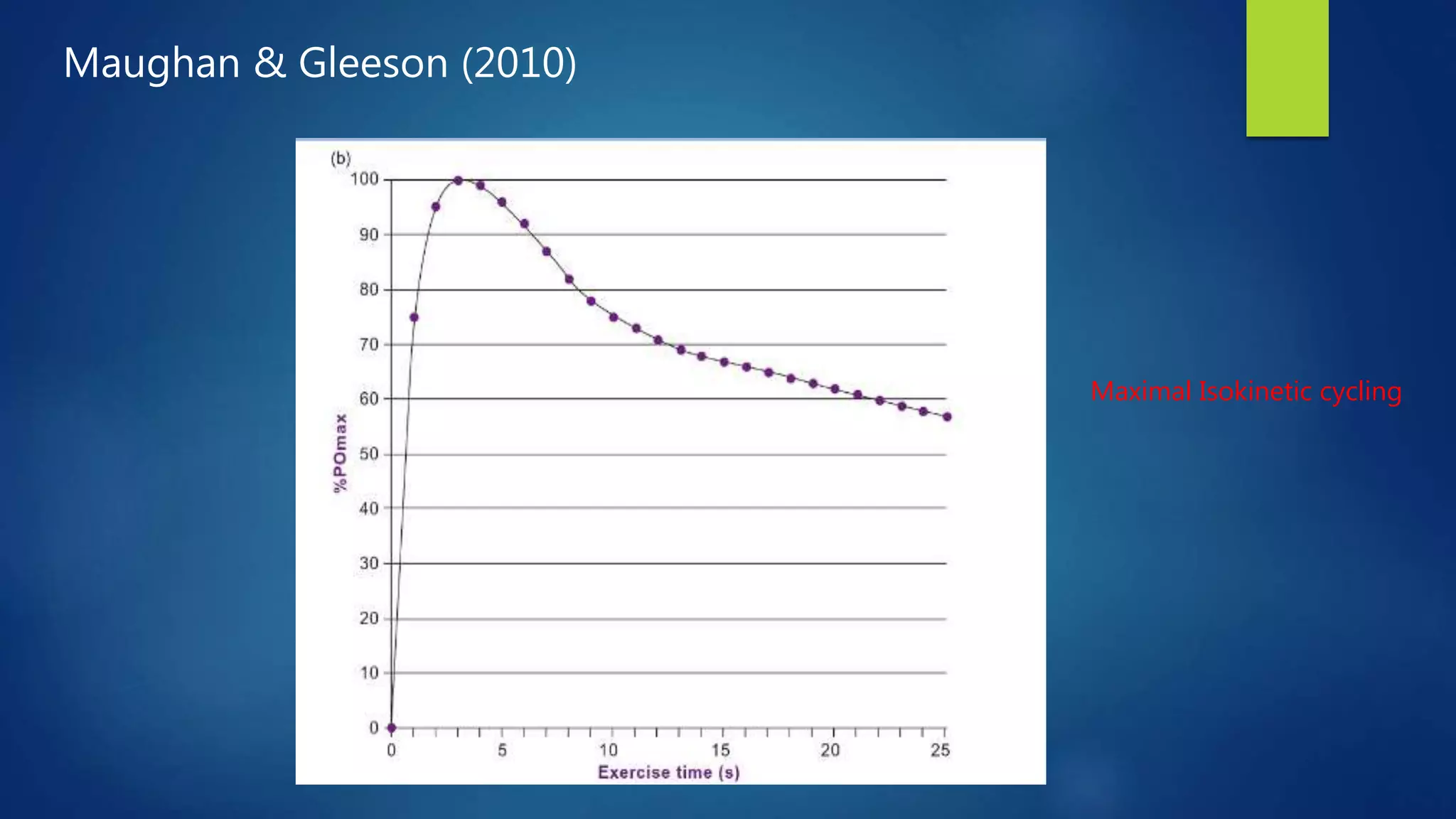

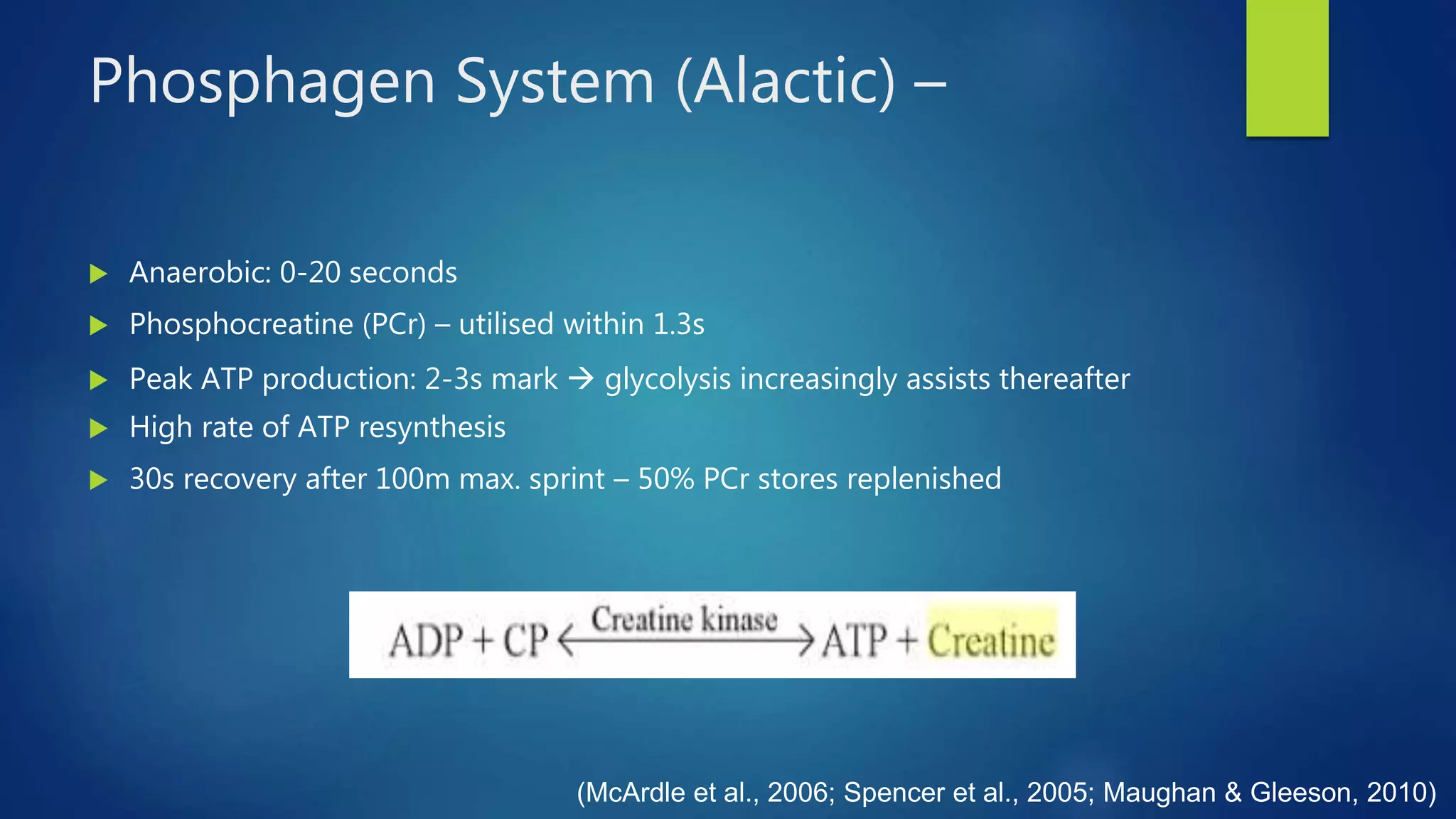

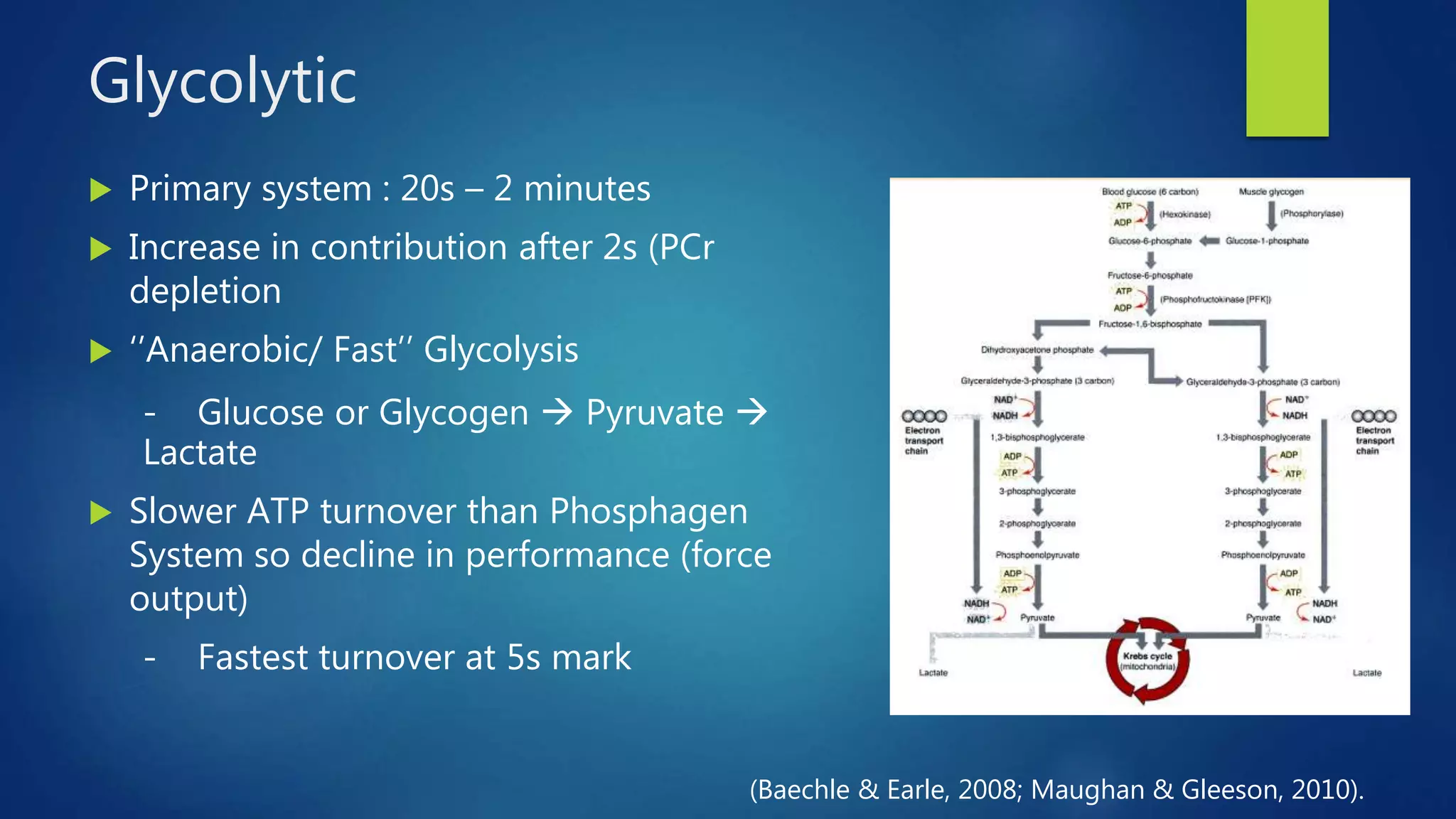

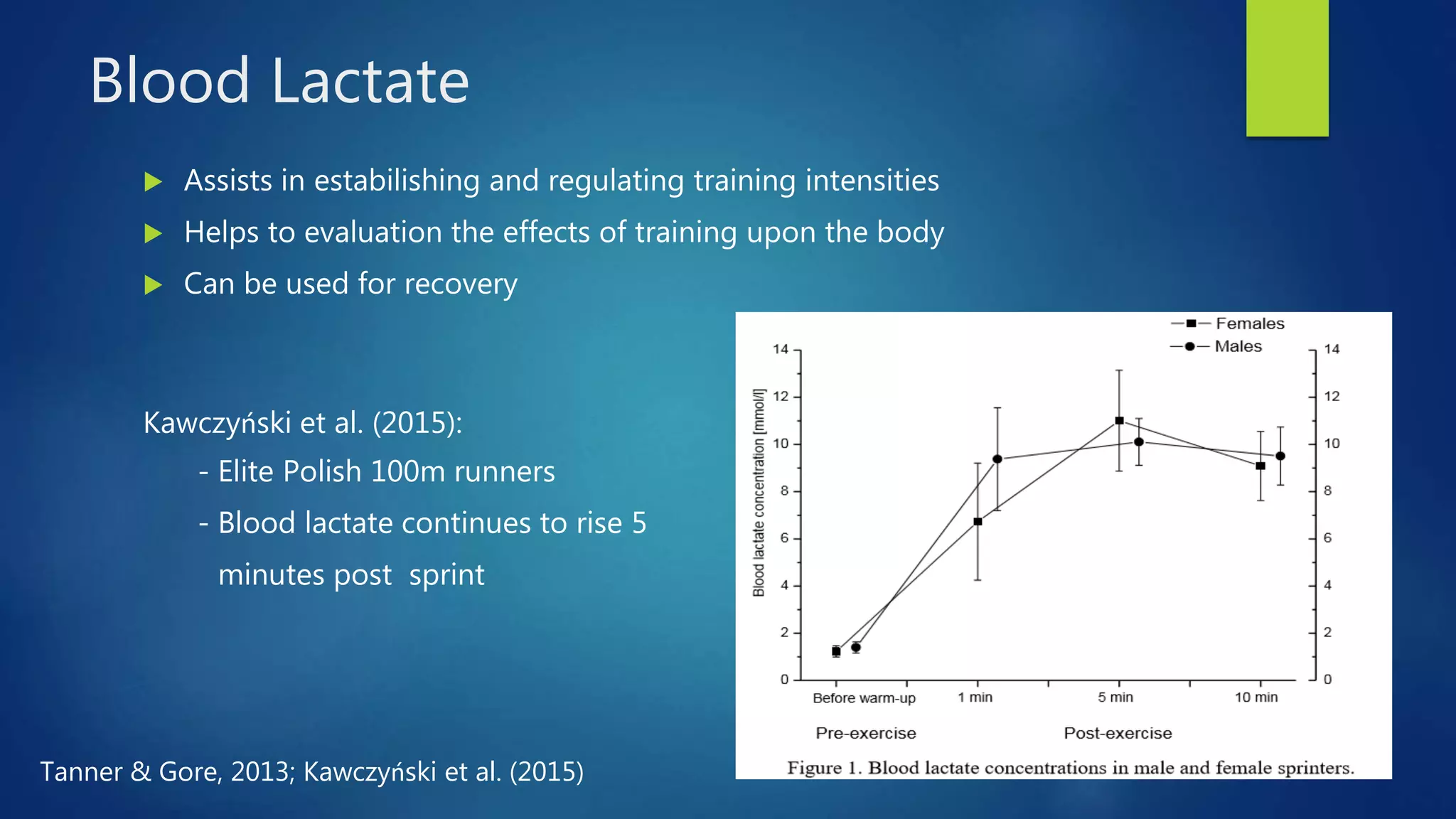

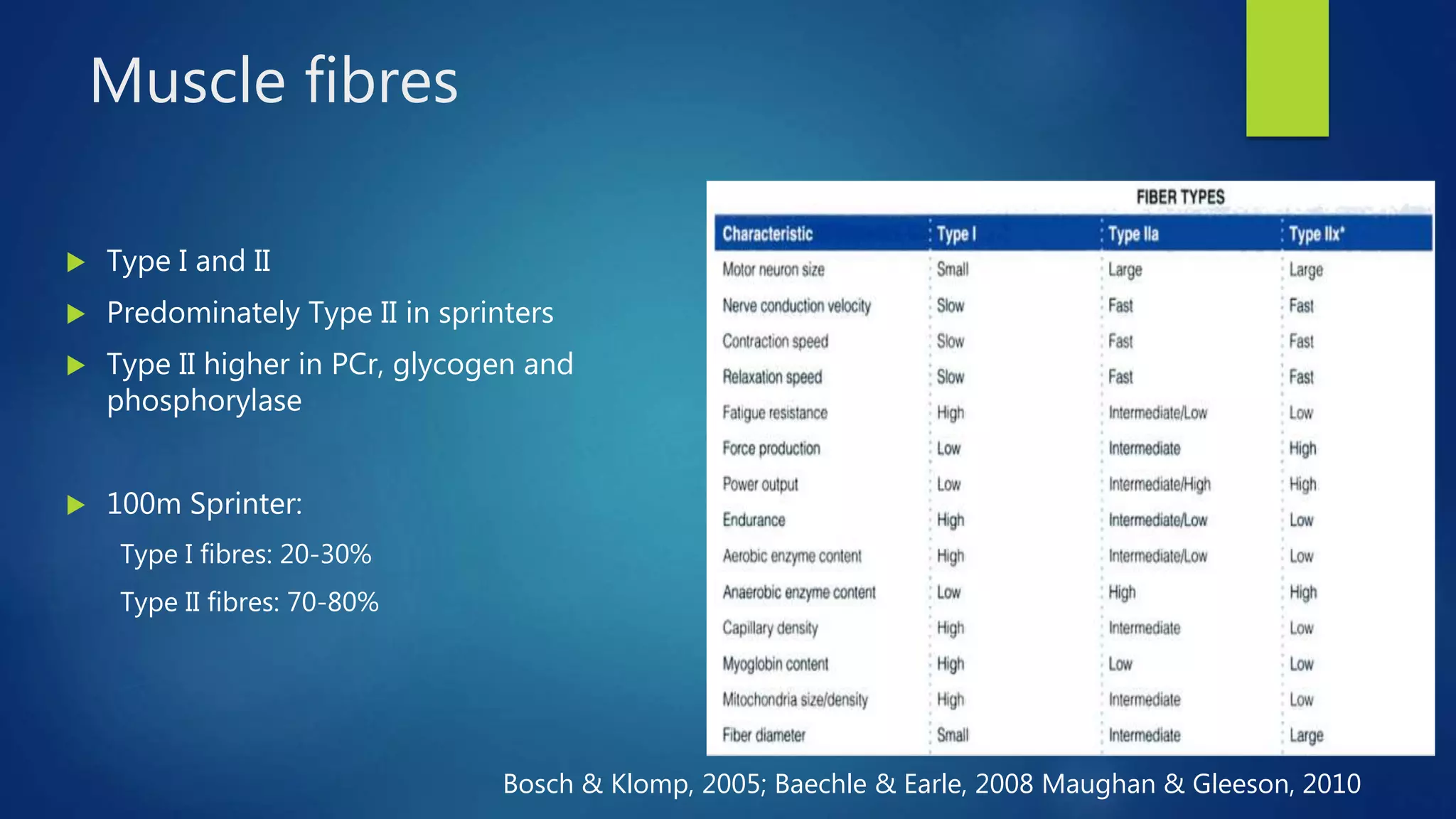

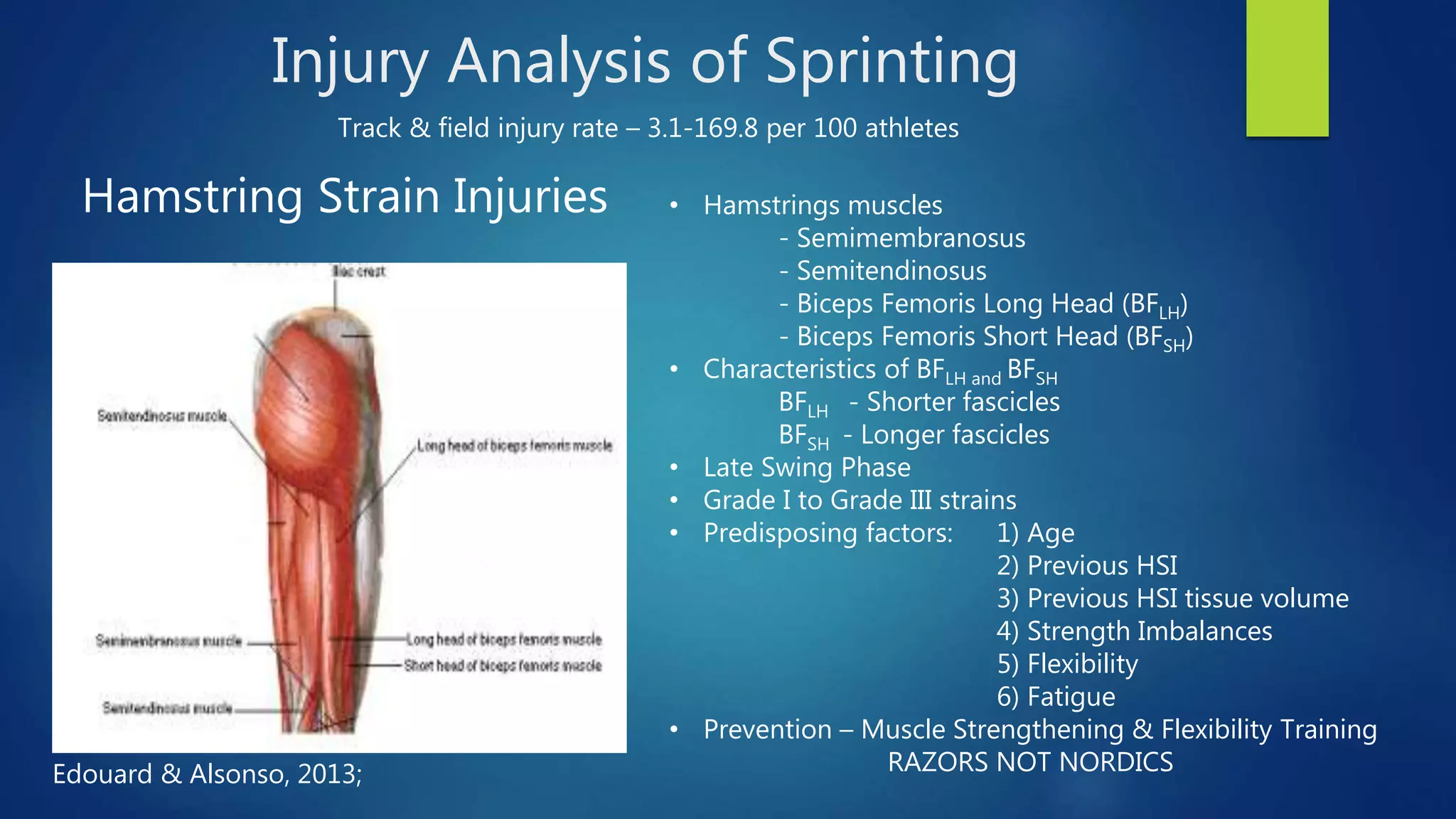

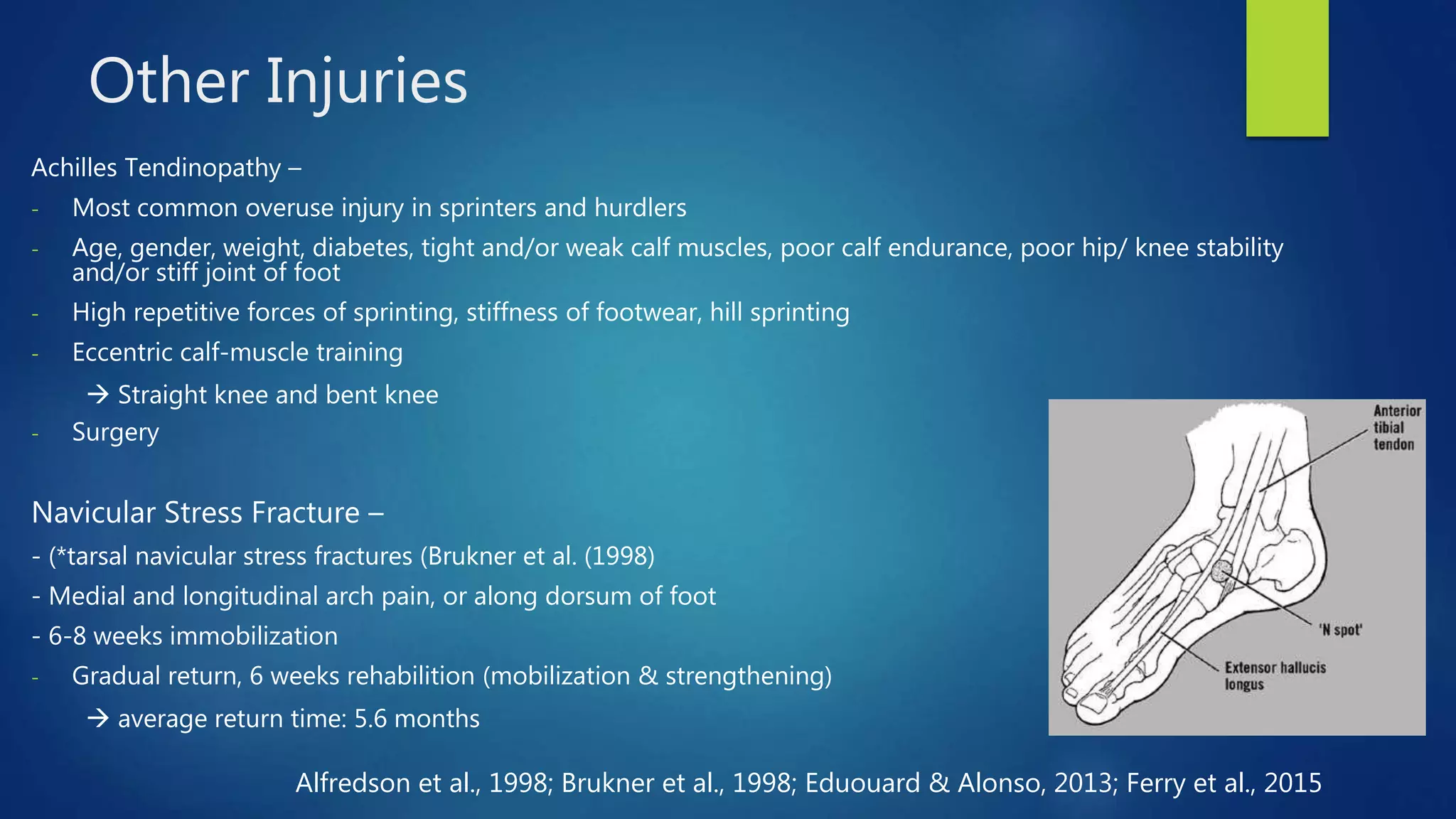

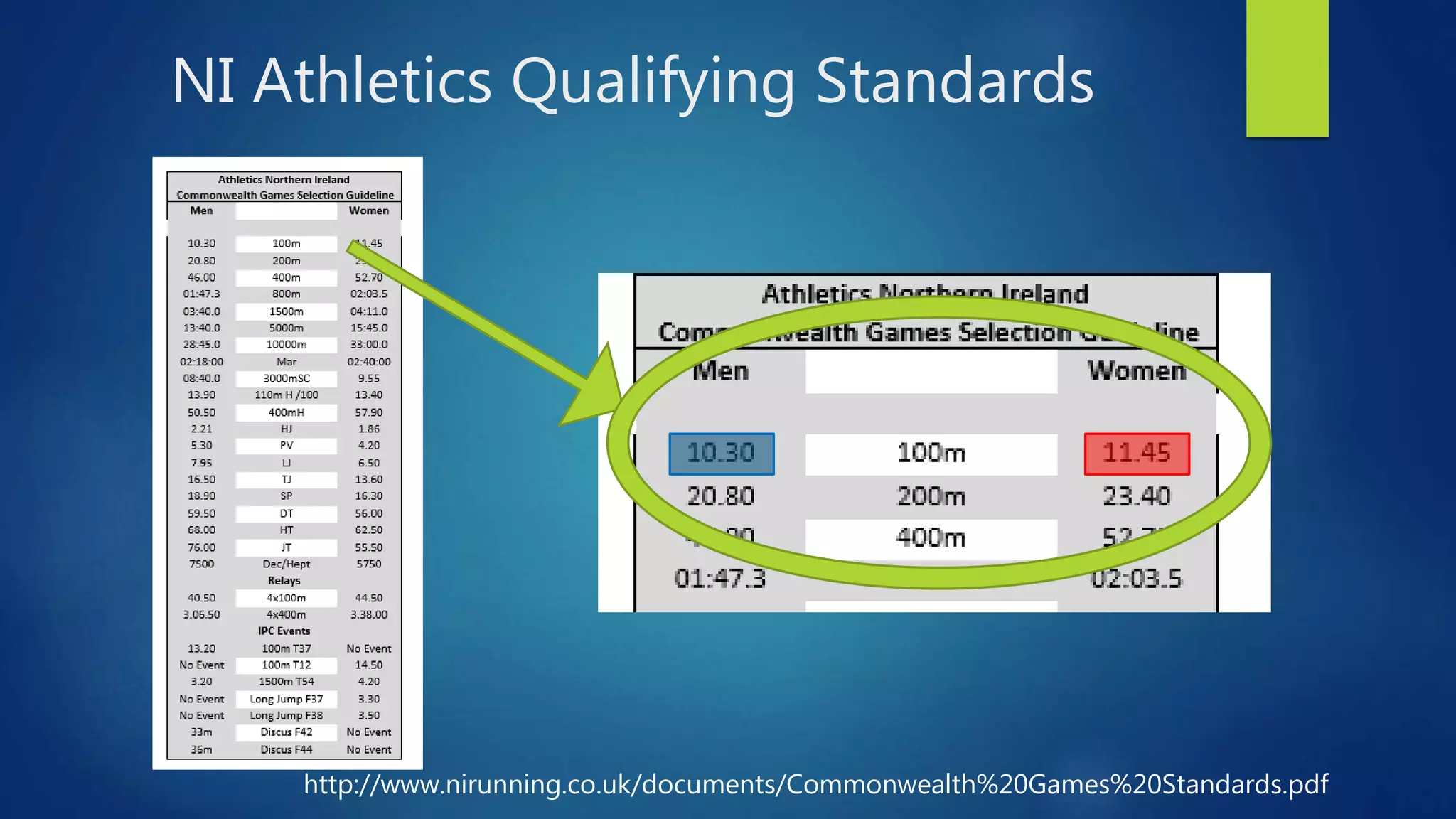

The document provides an in-depth needs analysis for the 100 metre sprint, covering key topics such as international athletics rules, movement patterns, energy systems, and injury mechanisms. It outlines training and testing approaches for sprinters, emphasizing strength, power, and optimal running mechanics to improve performance. Additionally, it discusses the physiological demands of sprinting and analyzes common injuries encountered in the sport.