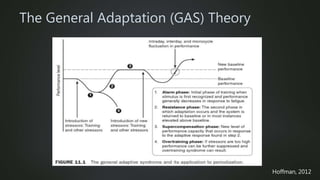

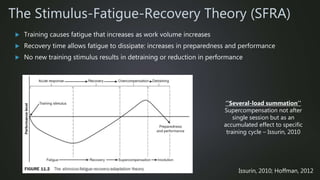

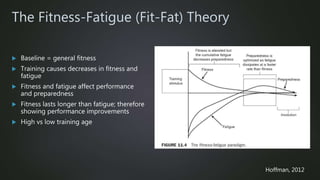

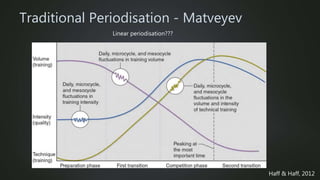

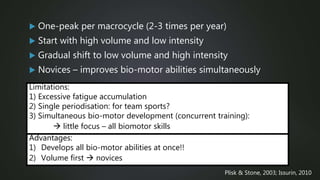

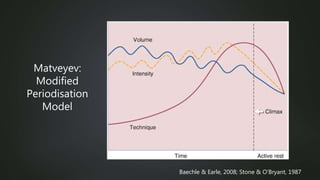

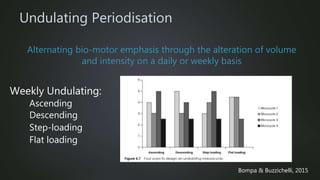

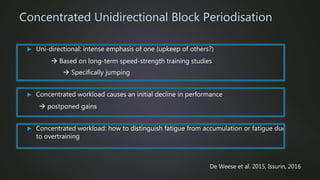

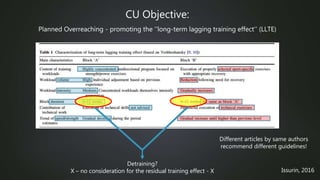

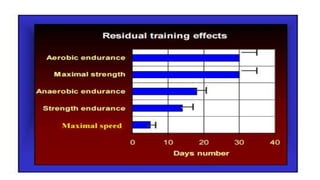

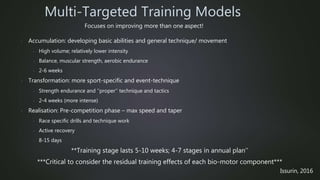

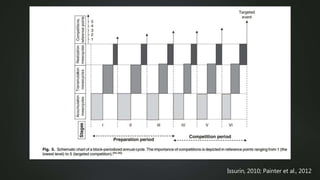

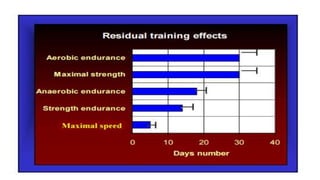

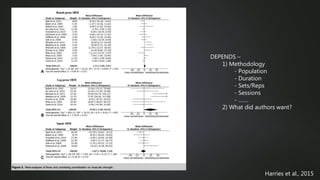

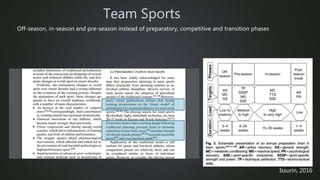

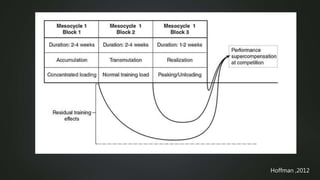

The document by Jill Costley outlines the concept of periodisation in athletic training, discussing its definition, purpose, and various models such as traditional, undulatory, and block periodisation. It emphasizes the need for structured phases in training—including preparatory, competitive, and transition phases—to optimize performance and manage fatigue. Additionally, it explores key theories on stress response and recovery that underpin periodisation, as well as practical applications through case studies and specific examples in sprinting.