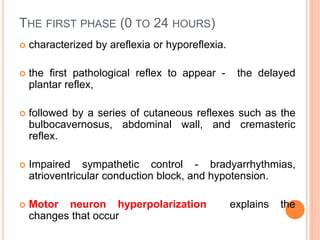

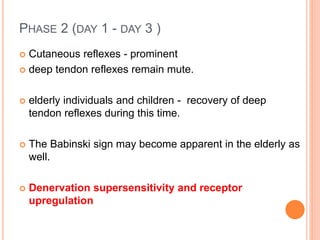

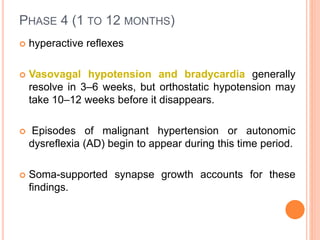

Spinal shock occurs after sudden spinal cord injury and is characterized by loss of motor and sensory function below the injury, along with loss of reflexes. It represents a lack of descending facilitation from the brain after damage to upper motor neurons. Spinal shock is thought to be caused by hyperpolarization of neurons below the injury due to loss of supraspinal input. It resolves over time in four phases as reflexes return gradually from the feet upwards over days to months.