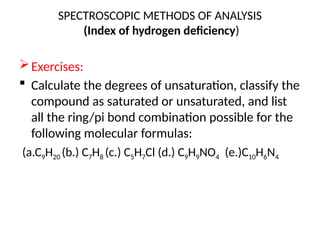

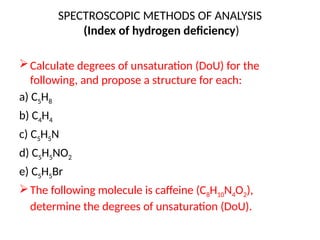

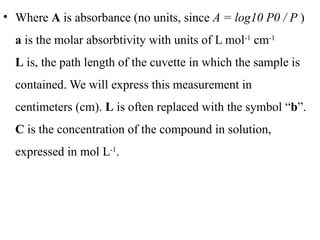

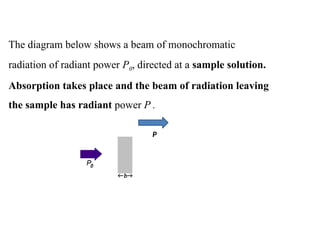

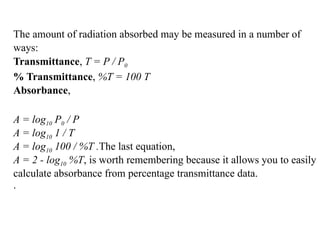

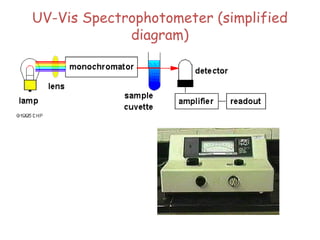

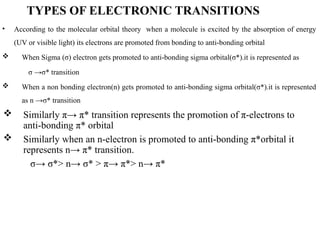

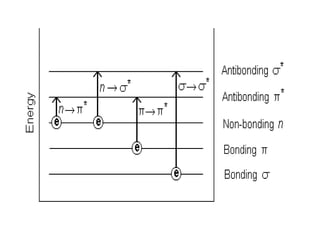

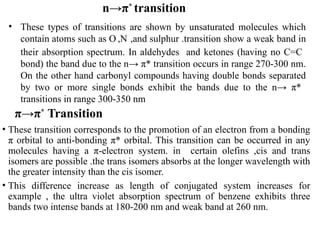

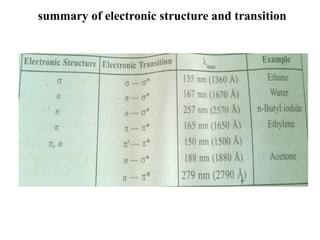

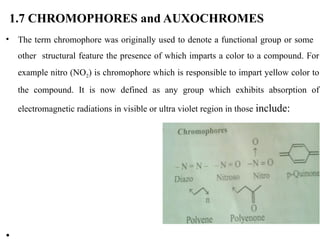

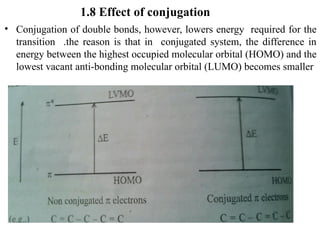

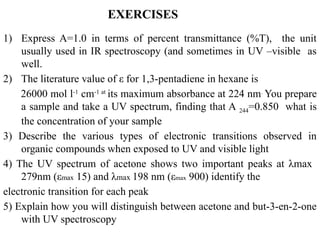

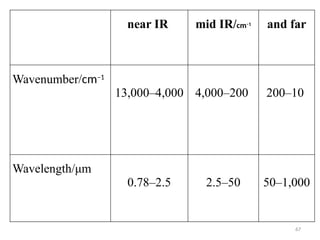

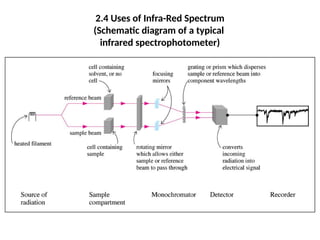

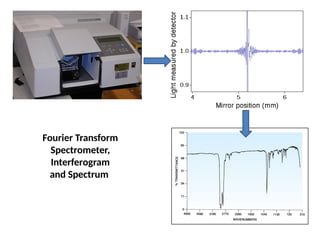

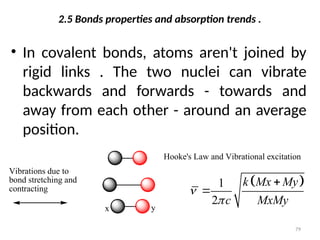

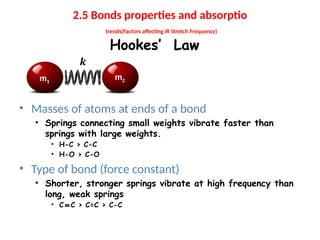

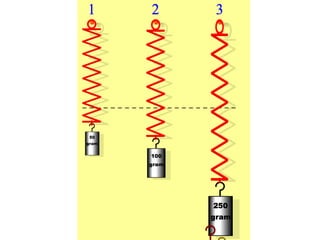

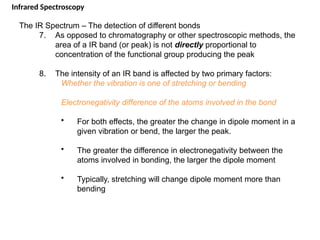

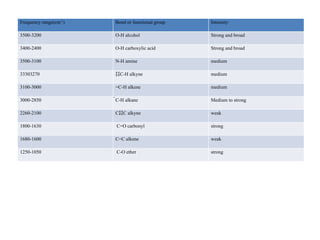

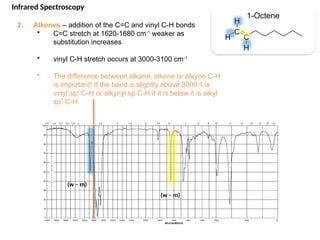

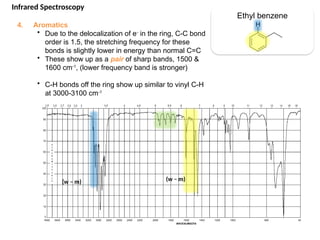

The document outlines the principles and techniques of various spectrometric methods used for chemical analysis, including UV-visible spectroscopy, infrared spectroscopy, mass spectrometry, and nuclear magnetic resonance spectroscopy. It describes the interaction of organic molecules with electromagnetic radiation, explaining concepts such as electronic transitions, absorption processes, and the calculation of the index of hydrogen deficiency for structural determination. Additionally, it provides details on instrumentation, the Beer-Lambert law, and different types of electronic transitions relevant to spectroscopic studies.