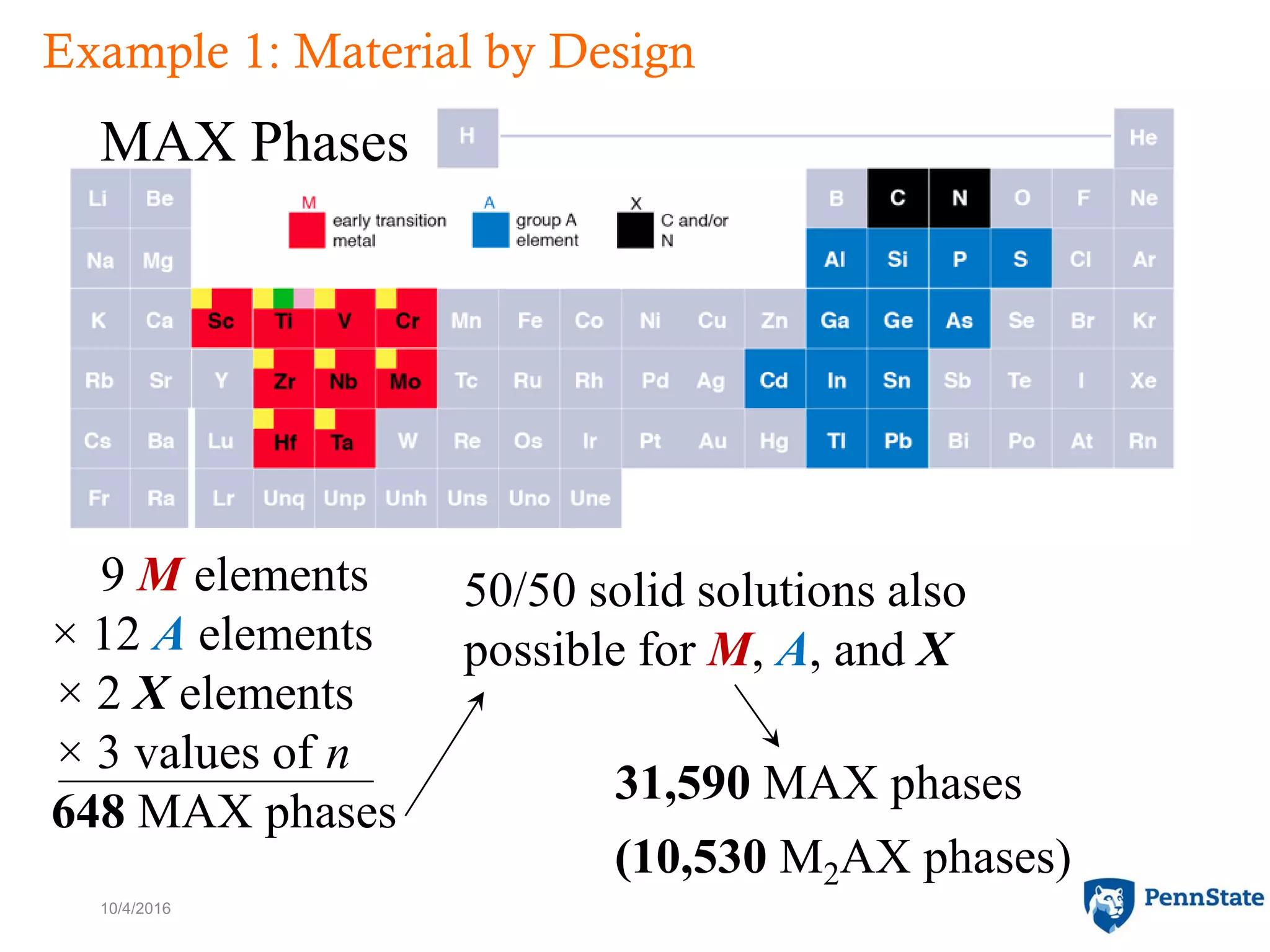

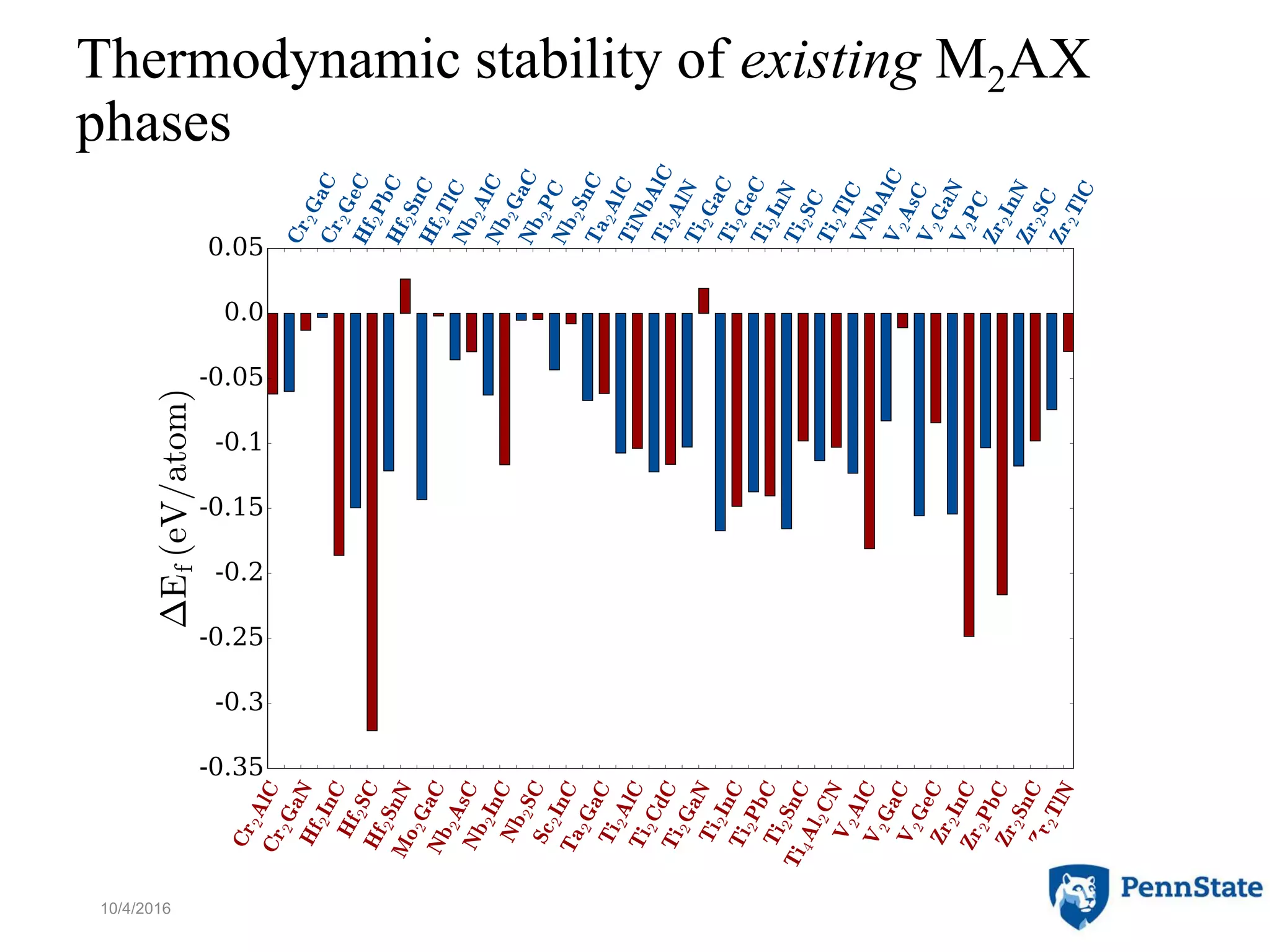

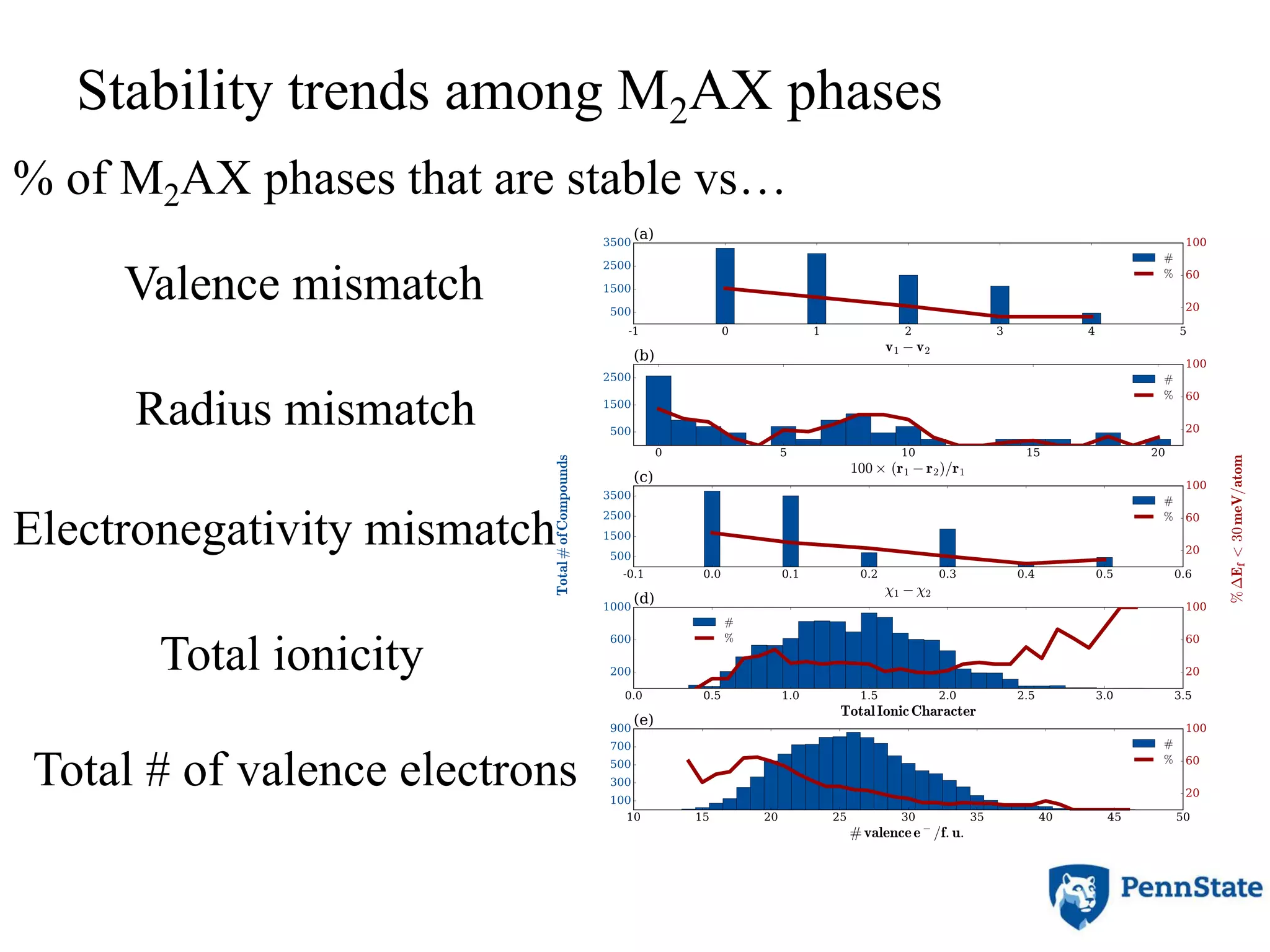

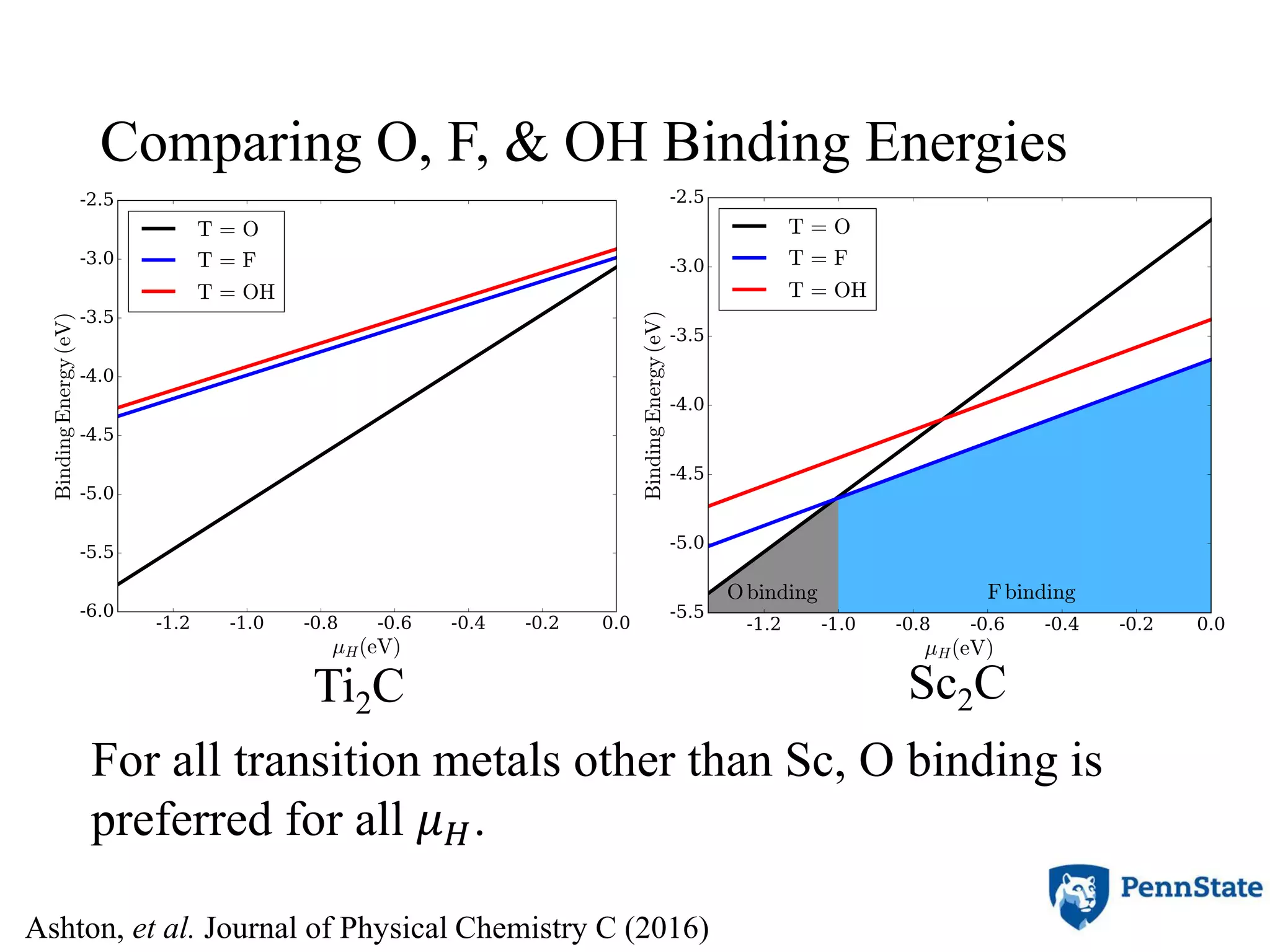

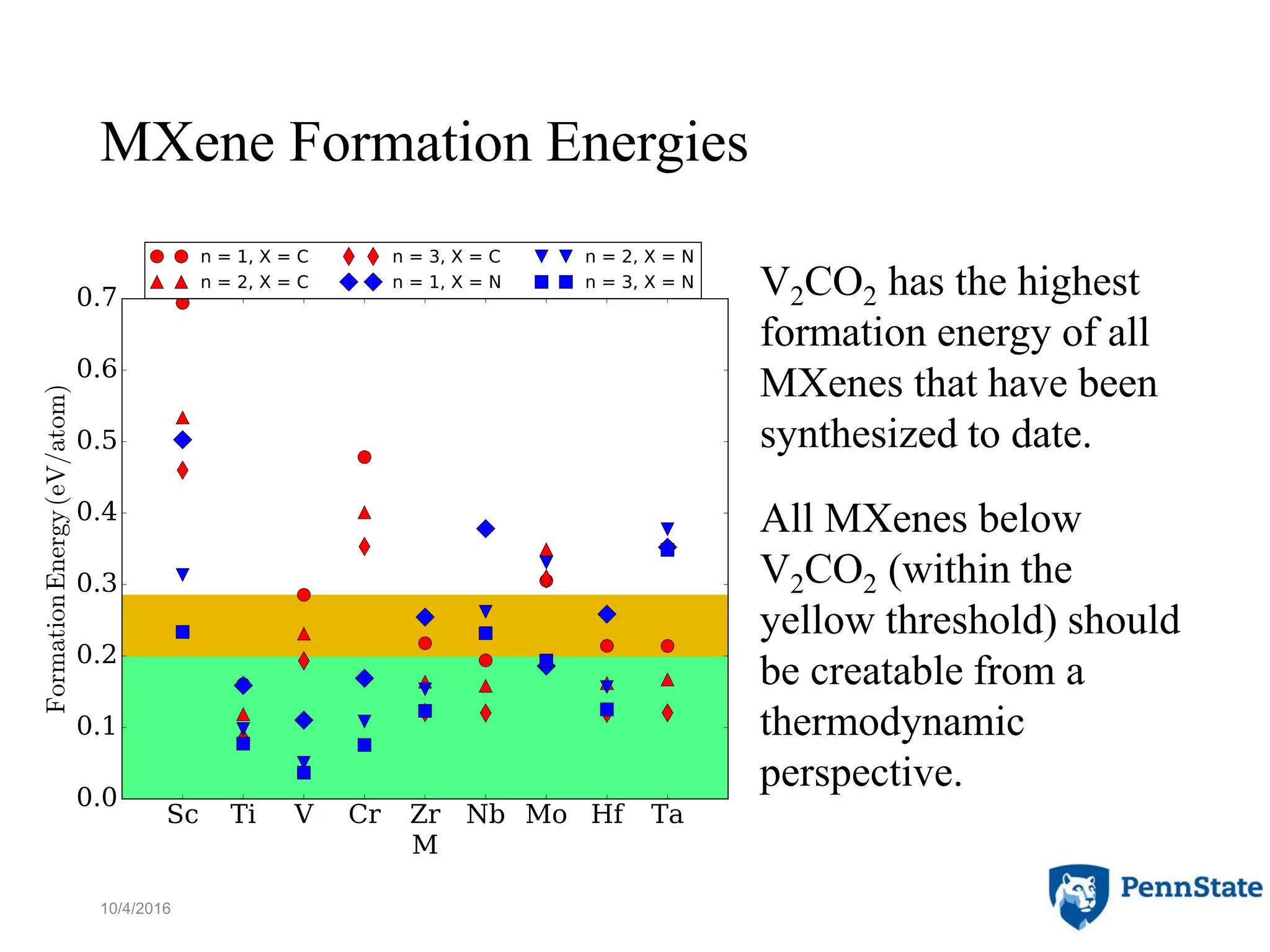

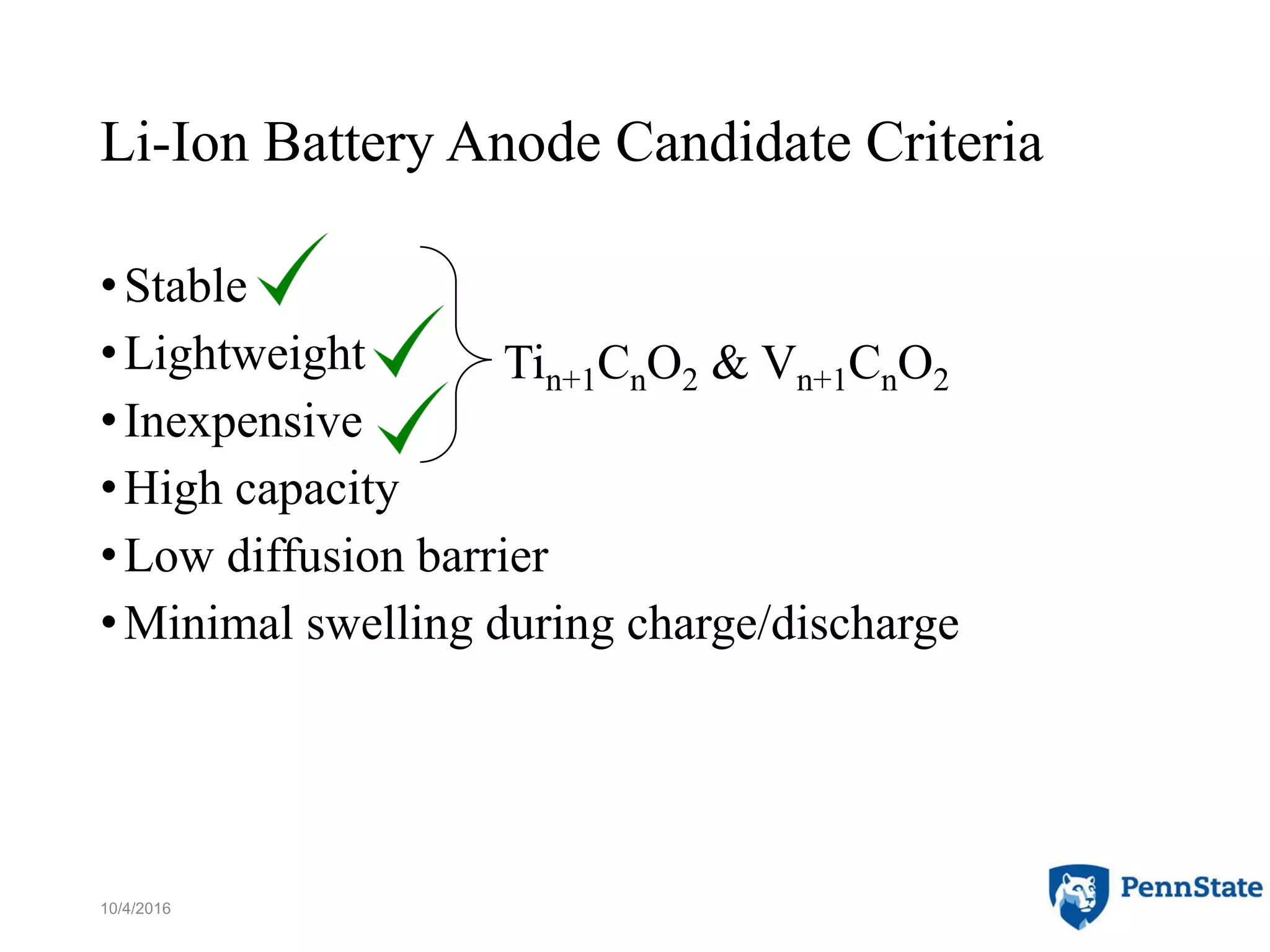

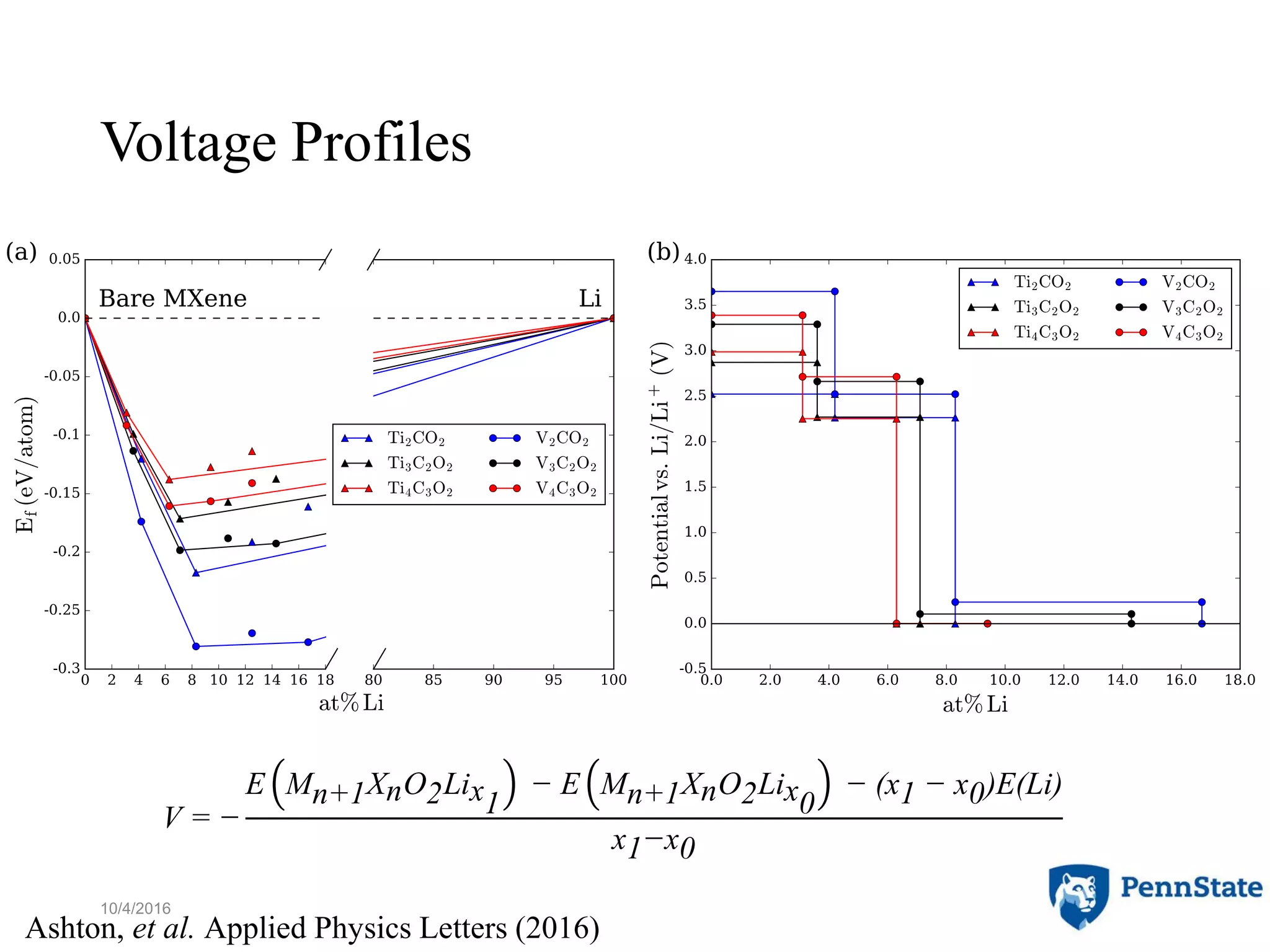

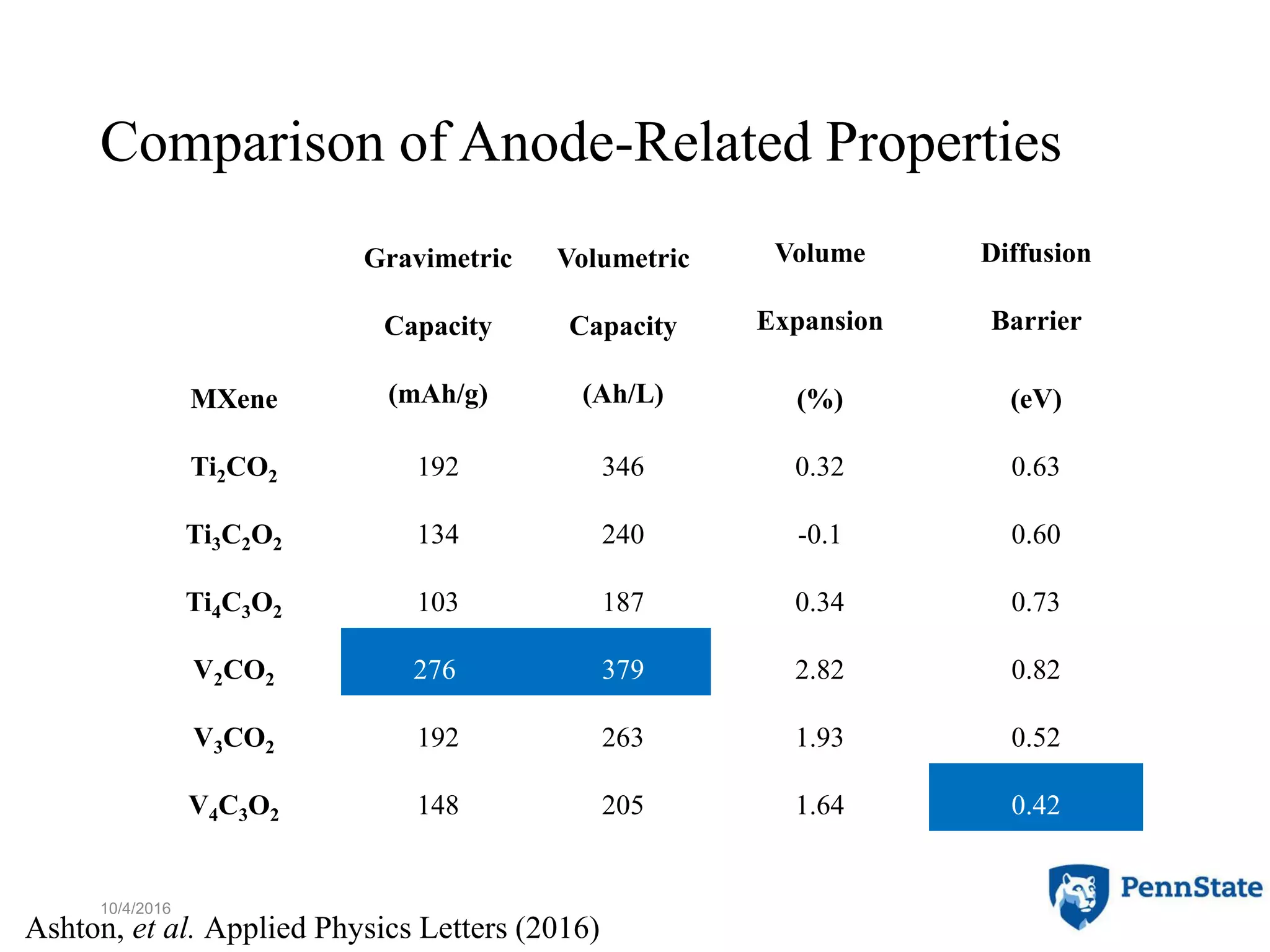

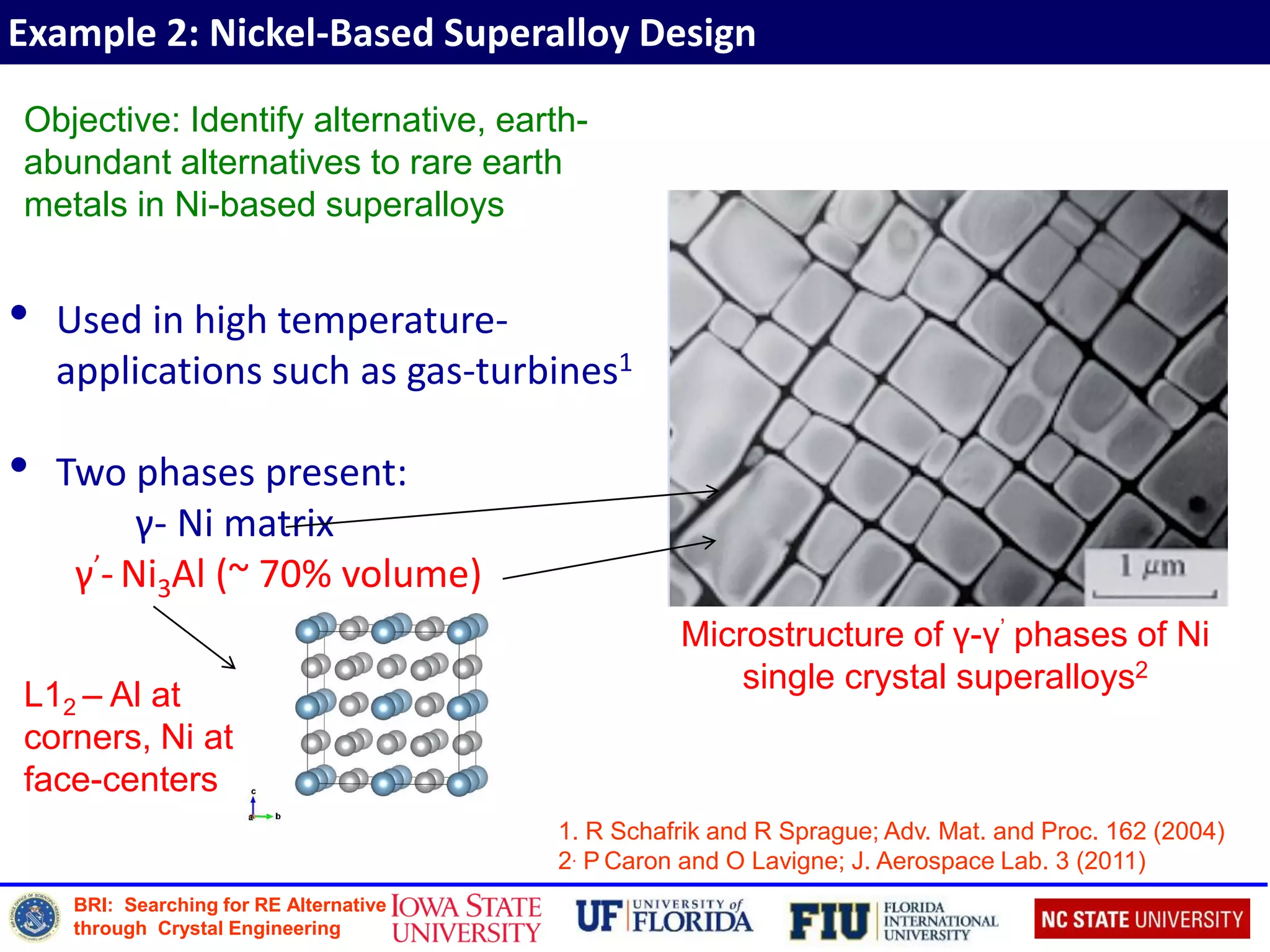

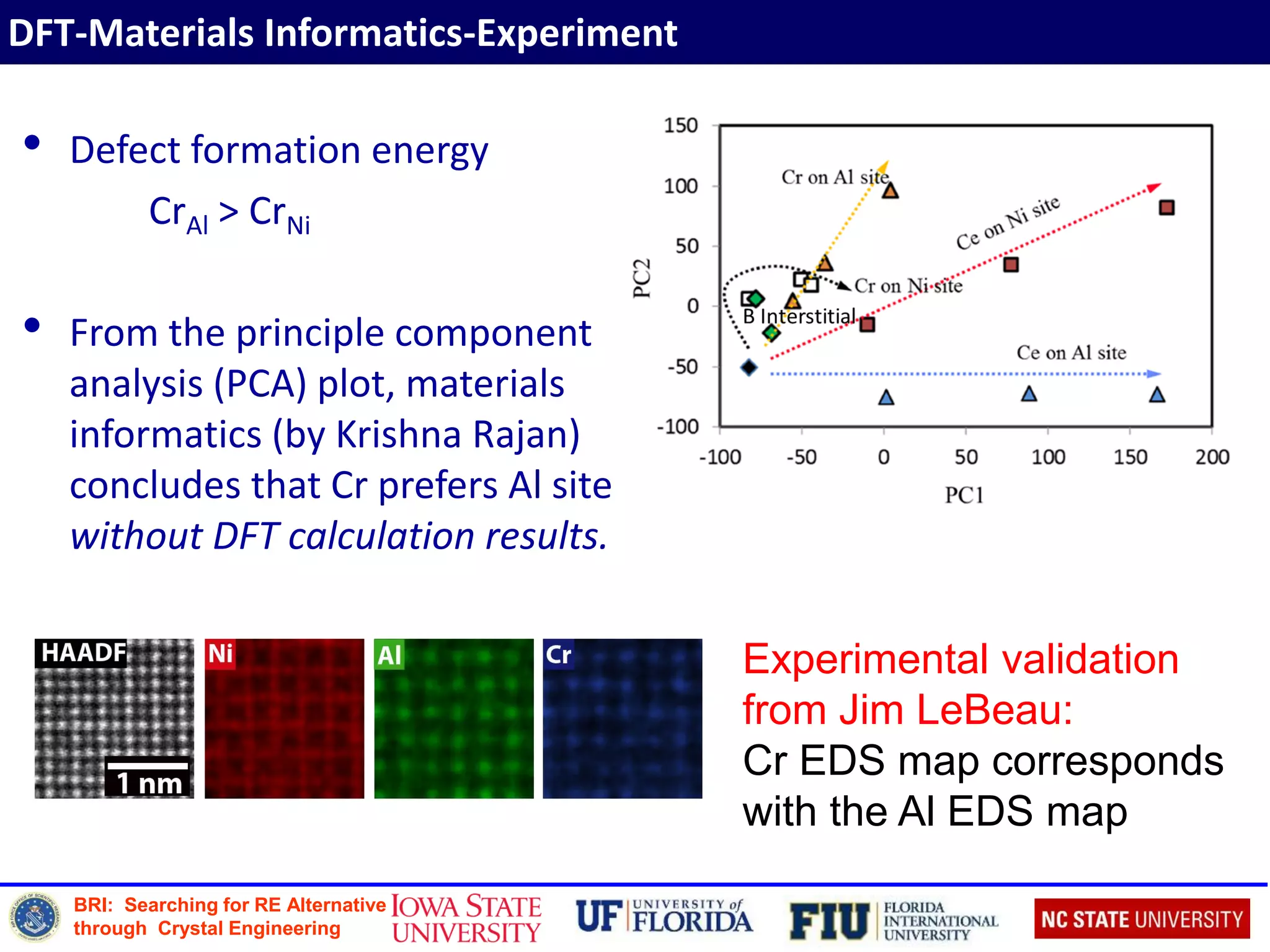

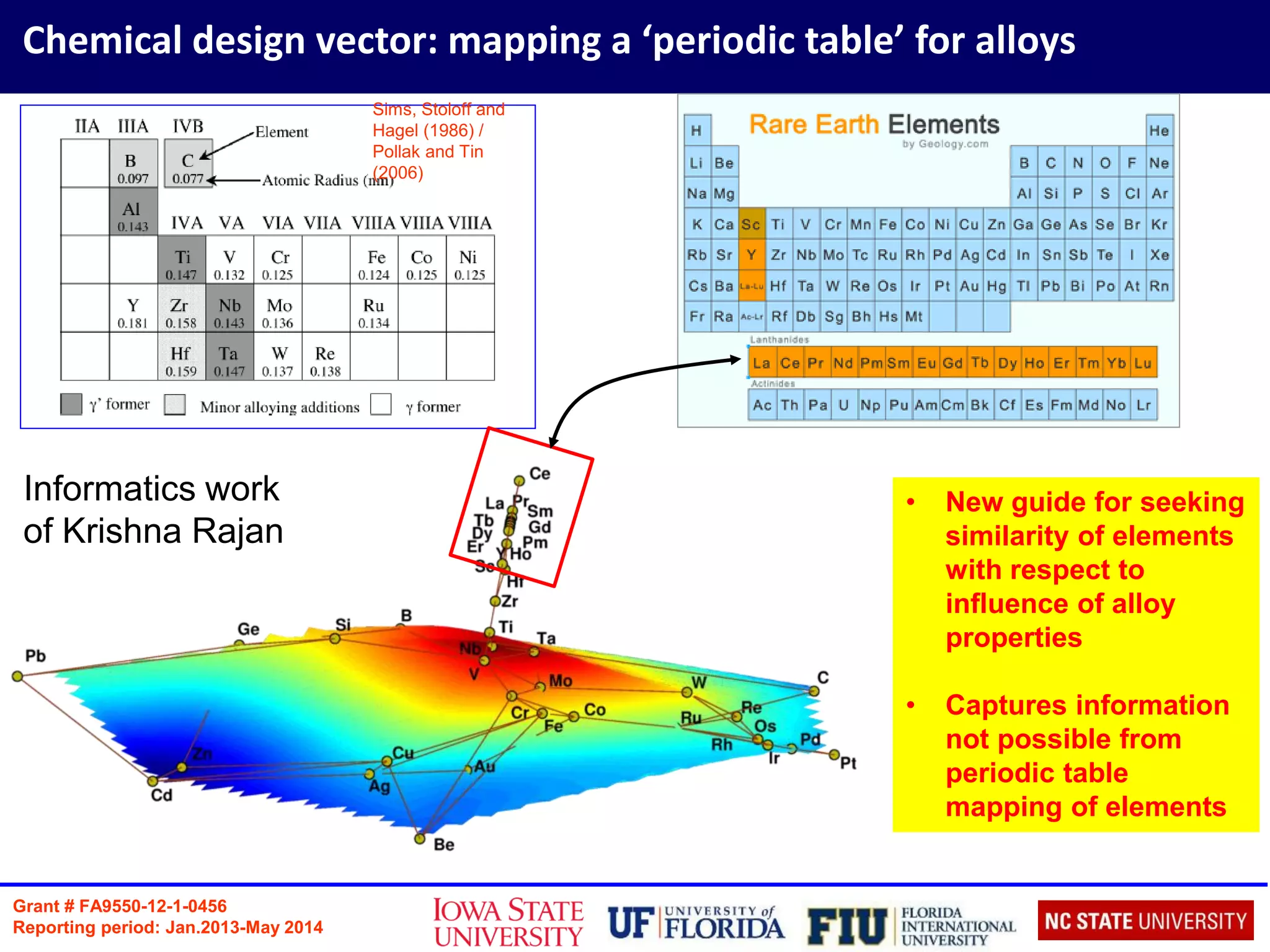

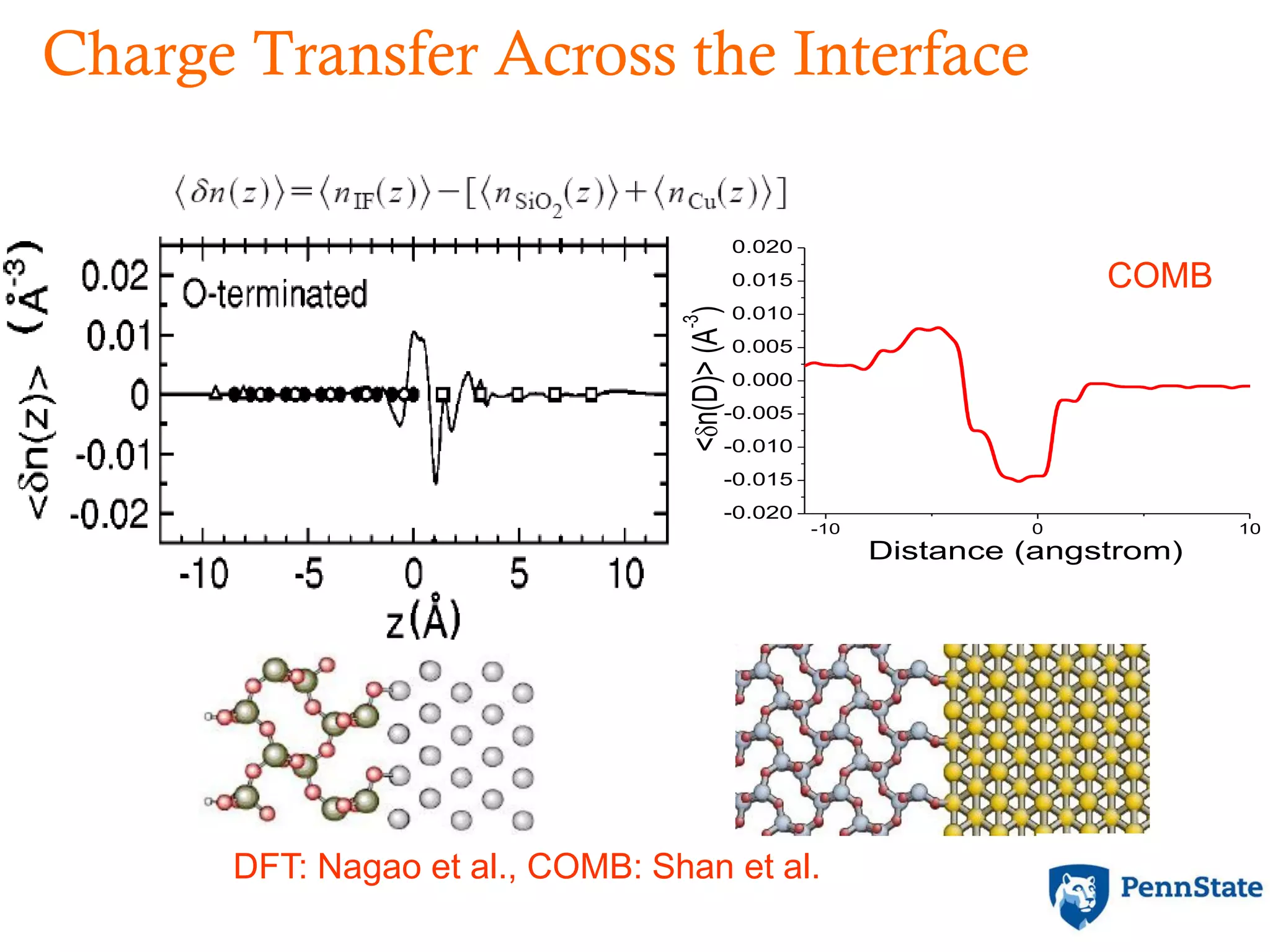

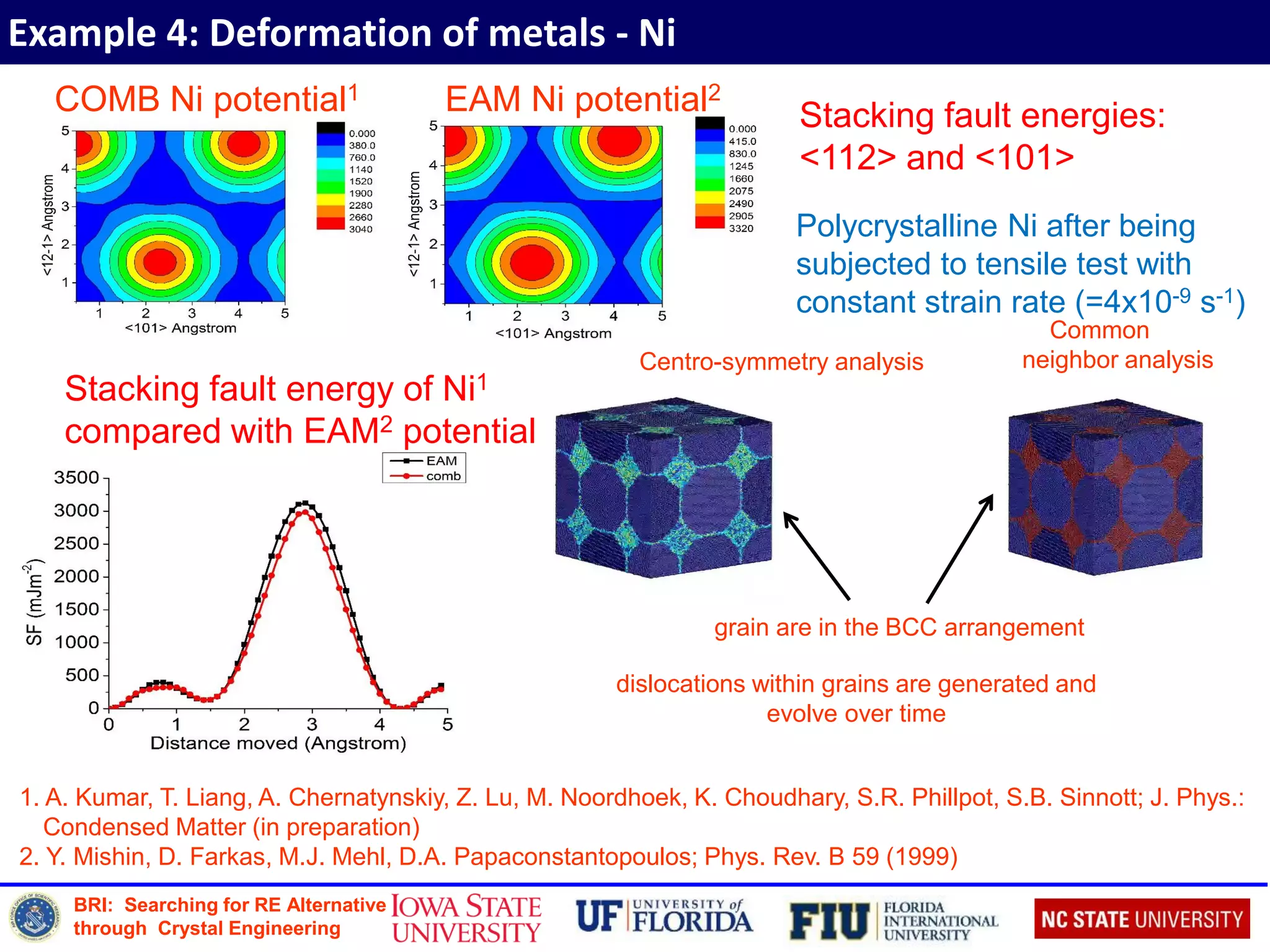

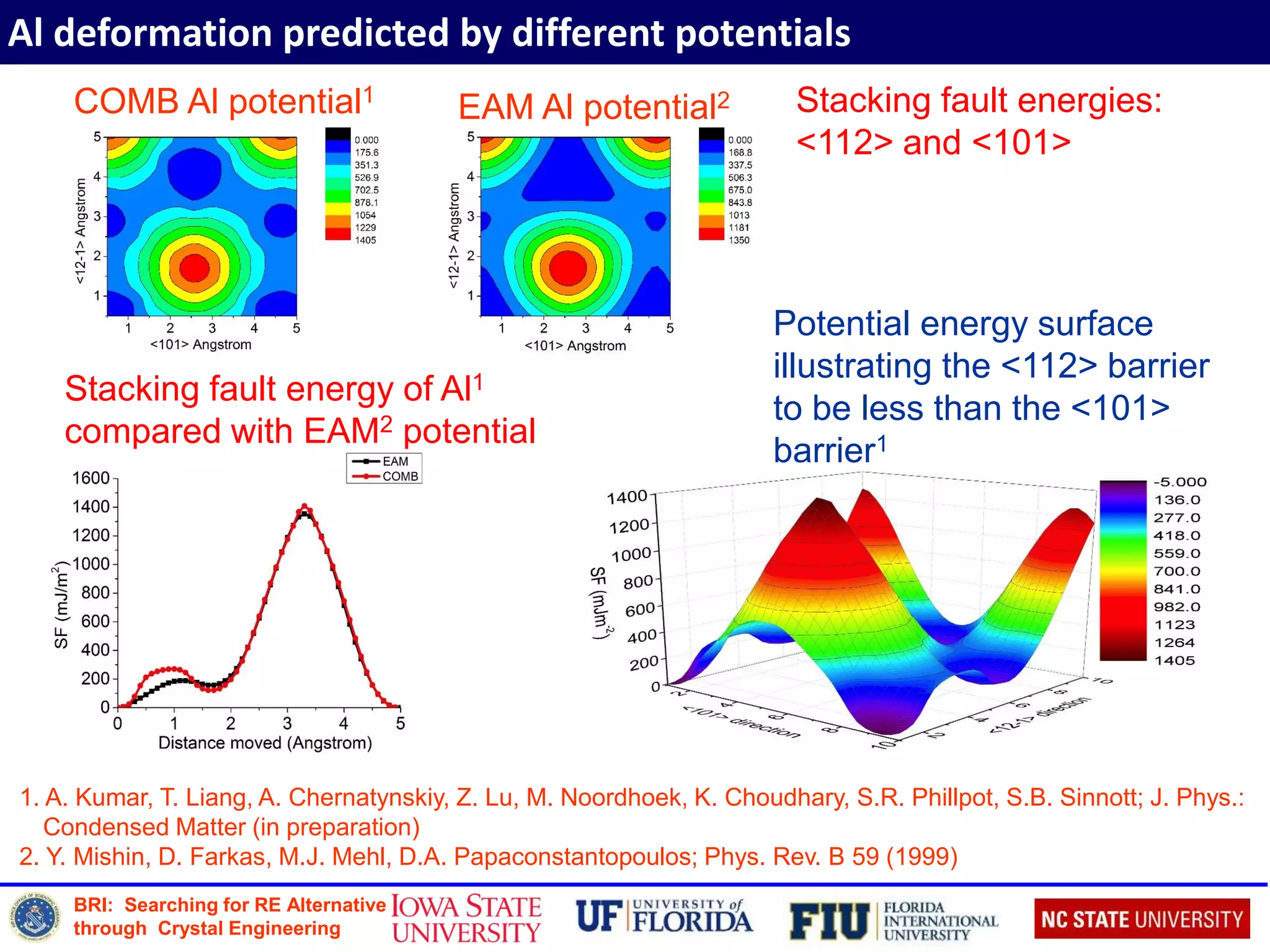

The document discusses the role of atomic-scale modeling in materials design and discovery, highlighting the use of high fidelity computational methods such as quantum chemical approaches and density functional theory. It explores various applications, including the design of M2AX phases, MXenes for battery anodes, and alternatives to rare earth metals in superalloys, emphasizing the importance of understanding fundamental atomic behaviors to inform broader scale models. Additionally, it addresses challenges in predictive modeling, the integration of computational approaches with experimental data, and the need for efficient cyberinfrastructure to facilitate materials research.

![Diffusion Pathways in Multilayer MXenes

10/4/2016 13

O (over)O (under) Li

(a) (b)

[0100]

[1000]

a

b

[1200]

[1100]

Monolayer Multilayer

ΔE (eV)

1.0

2.0

3.0

4.0](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2016sinnottbrazilmrs-161005210537/75/Role-of-Atomic-Scale-Modeling-in-Materials-Design-Discovery-13-2048.jpg)

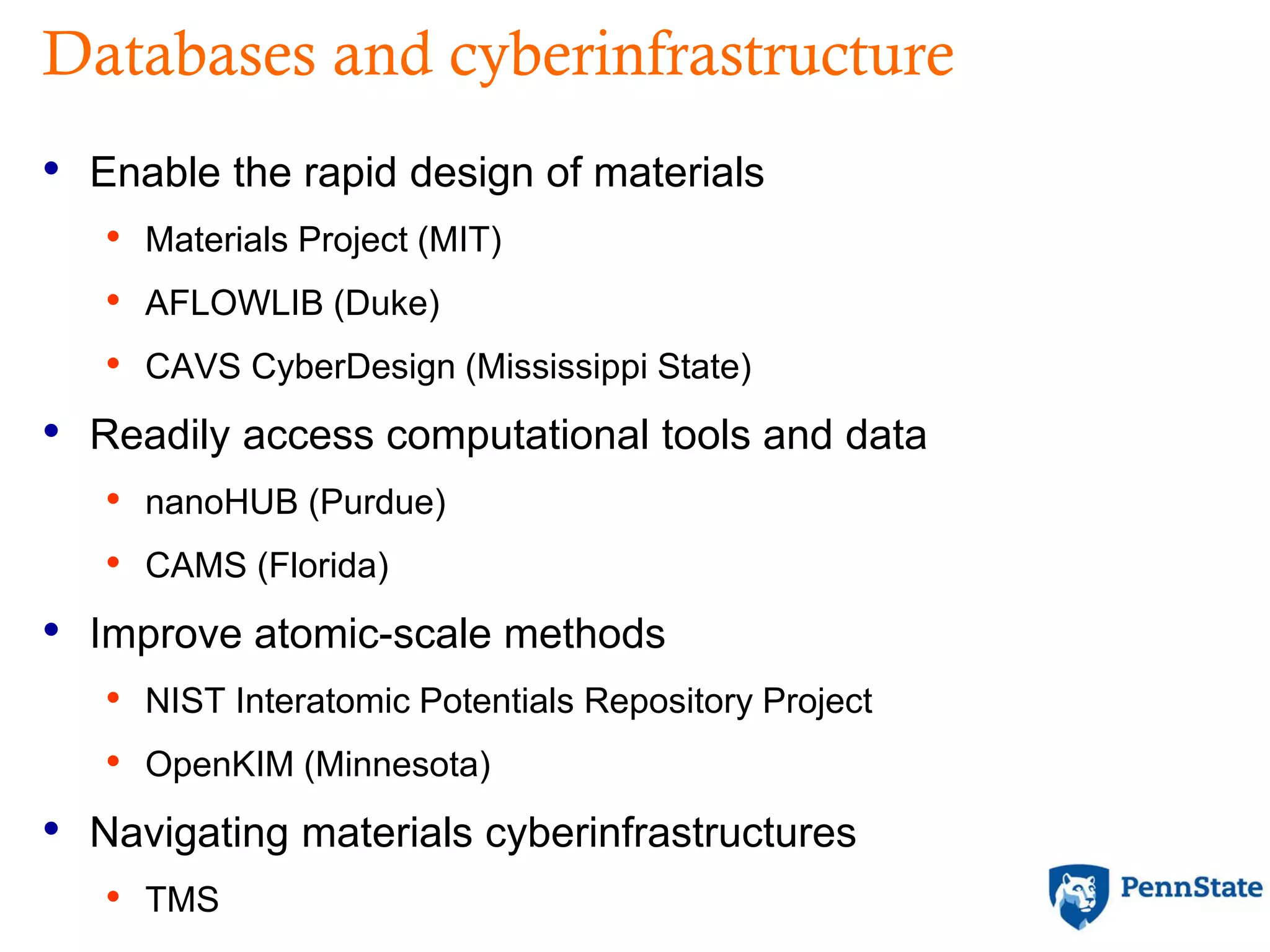

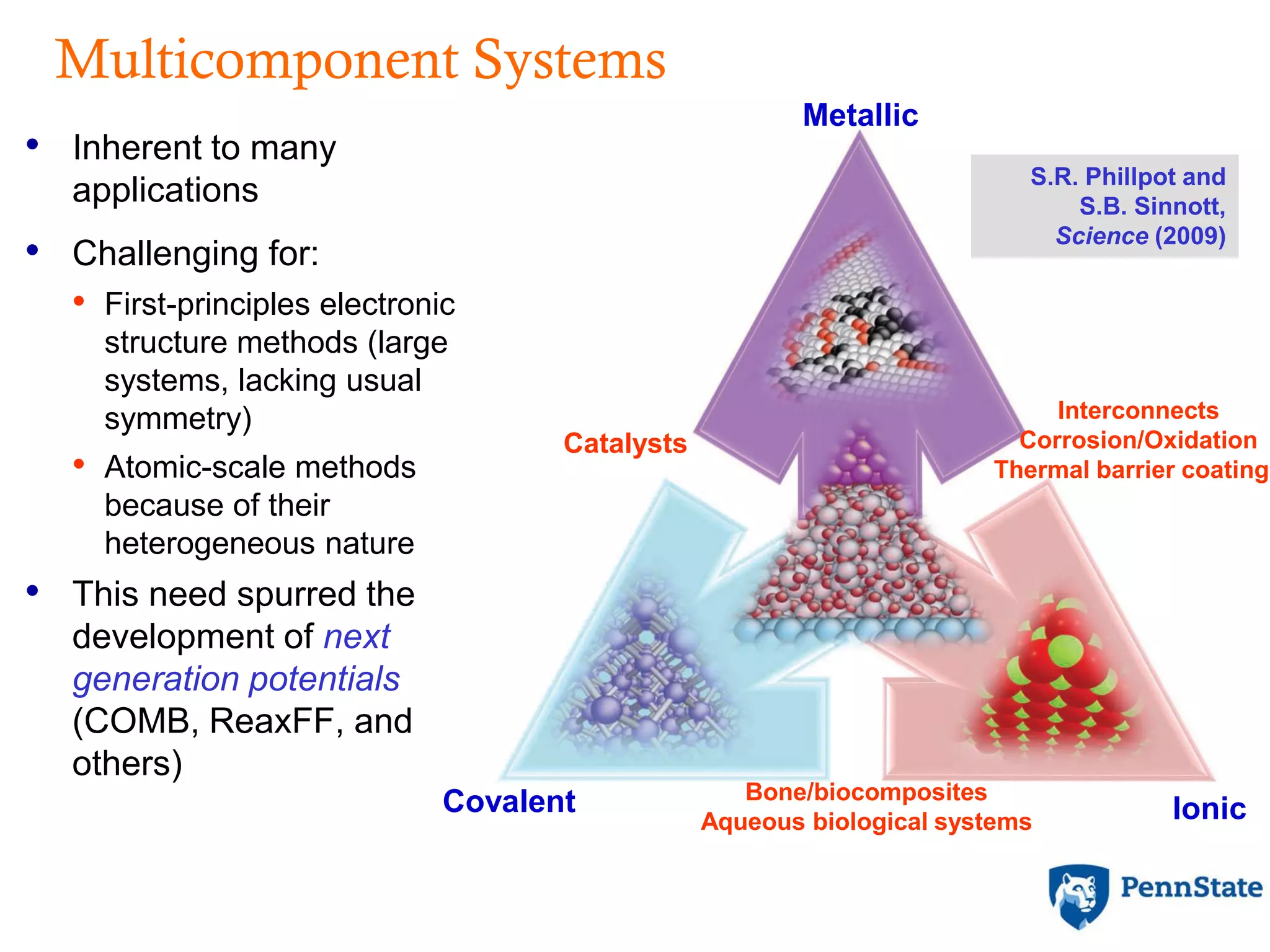

![BRI: Searching for RE Alternative

through Crystal Engineering

Defect Formation Energy

Defect formation energy of incorporating dopant X is defined as:

Etot[Xq] = total energy of the system with the defect

Etot[bulk] = total energy of the system without the defect

n = number of atoms added (n > 0) or removed (n < 0)

μi = chemical potential of species i

X Ef (XAl) (eV) Ef (XNi) (eV)

B 2.60 0.87

Cr 1.40 (1.351) 0.93 (0.921)

Ce 0.81 1.81

Zr 0.10 (0.041) 0.31 (0.201)

1. D E Kim, S L Shang, Z K Liu; Intermetallics 18 (2010)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2016sinnottbrazilmrs-161005210537/75/Role-of-Atomic-Scale-Modeling-in-Materials-Design-Discovery-17-2048.jpg)

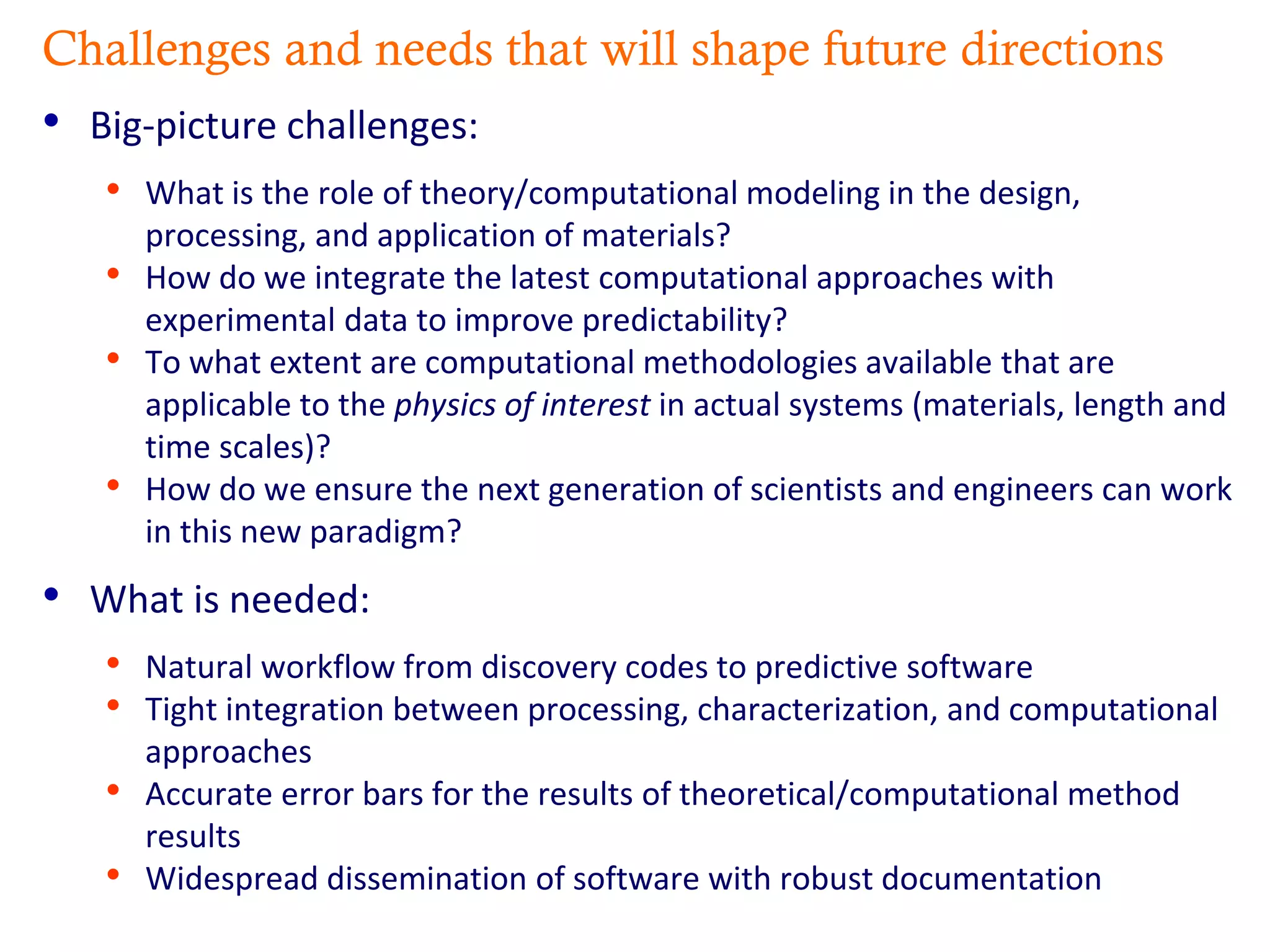

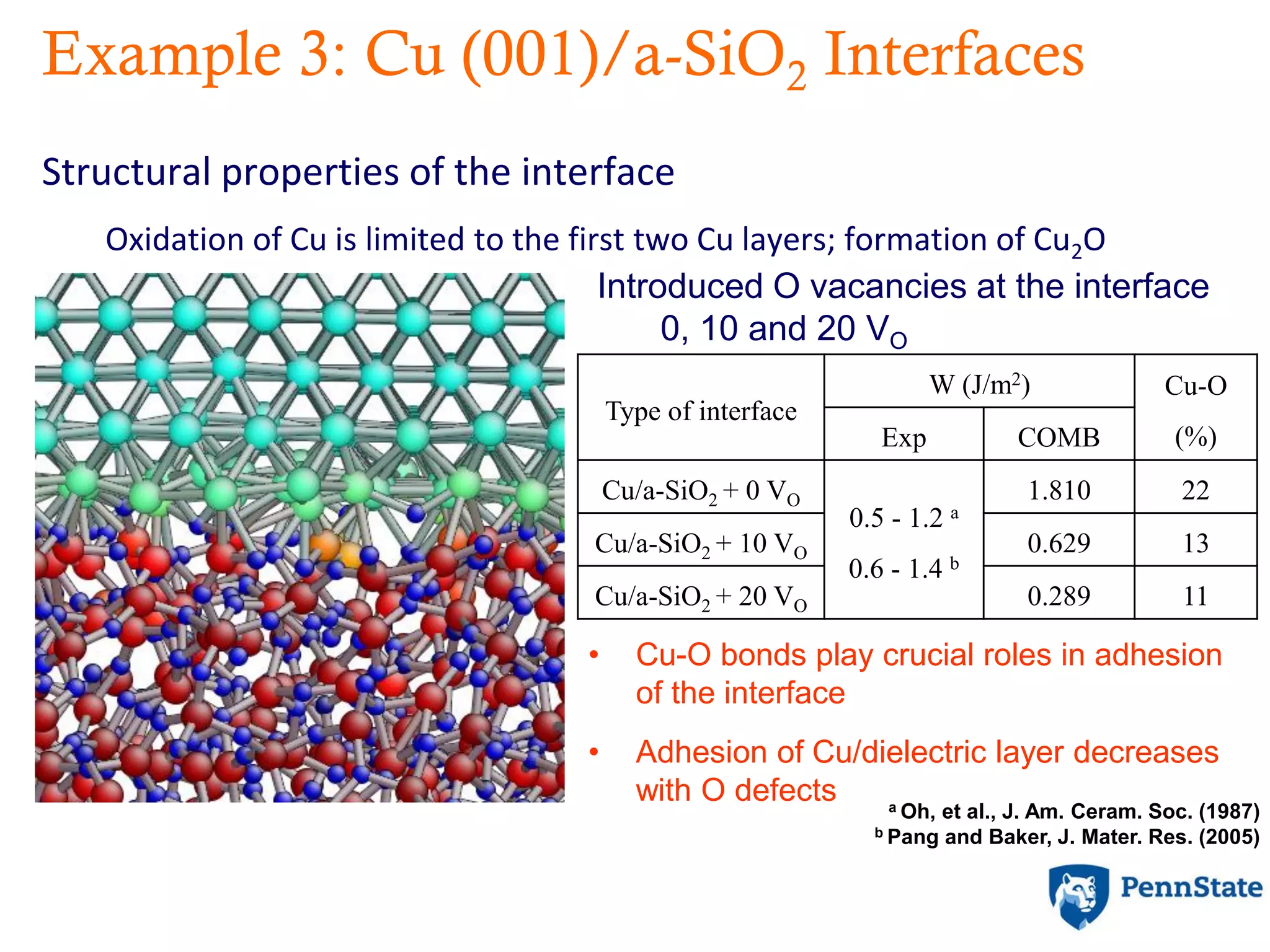

![BRI: Searching for RE Alternative

through Crystal Engineering

Mechanical deformation of Ni3Al at the g/g’ interface

1. A. Kumar, T. Liang, A. Chernatynskiy, Z. Lu, M. Noordhoek, K. Choudhary, S. R. Phillpot, S.B. Sinnott (in

preparation)

2. M.H. Yoo, M.S. Daw, M.I. Baskes, V. Vitek, D.J. Srolovitz, Eds.; New York: Plenum Press; 1989. p. 401.

Thermostat

Active

Rigid moving

Rigid moving

Thermostat

Active

Ni3Al

Ni

τzx

Z

[010]

X

[101]

Y

[10 -1]

τzx

• Edge dislocations at the Ni-Ni3Al interface

• Predict mechanisms associated with

applied shear stress and dislocation

motion

Ni3Al Ec

(eV/atom)

B

(GPa)

G

(GPa)

COMB1 -4.61 198 93

exp.2 -4.62 195 96

Simulation box size:

16.67x16.67x9.21 nm3

Total number of

atoms: 179,600

Dislocation](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/2016sinnottbrazilmrs-161005210537/75/Role-of-Atomic-Scale-Modeling-in-Materials-Design-Discovery-27-2048.jpg)