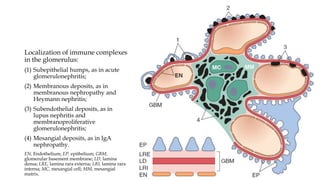

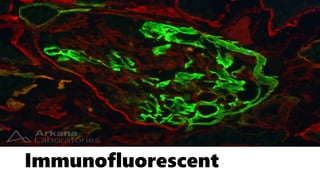

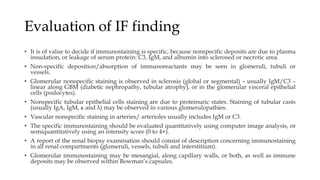

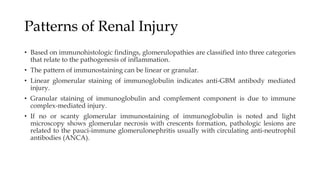

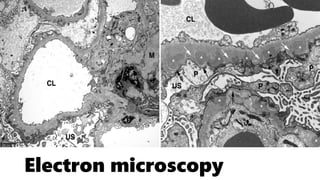

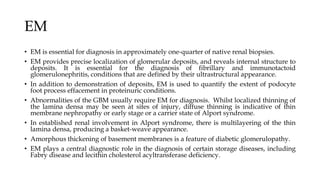

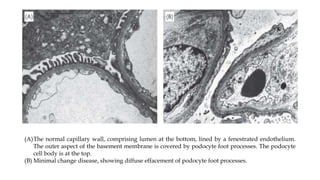

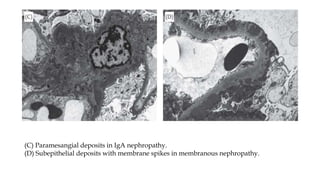

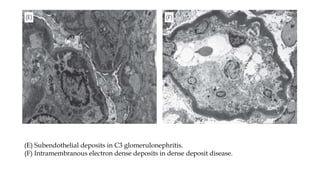

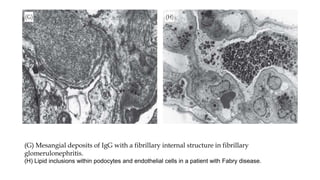

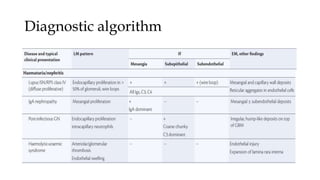

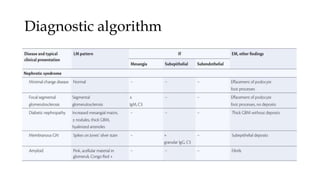

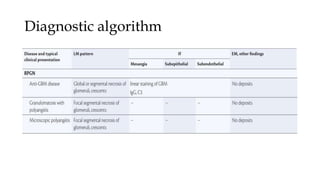

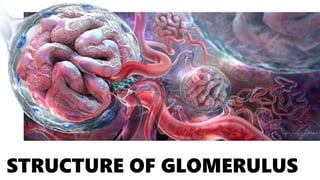

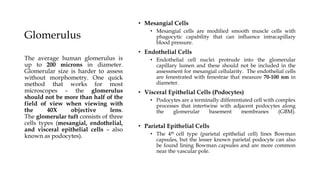

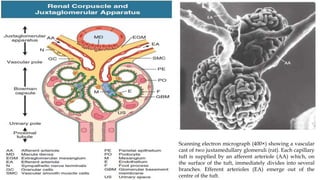

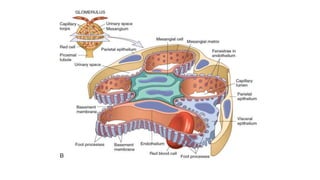

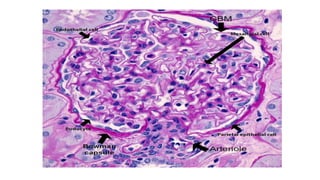

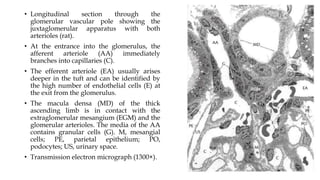

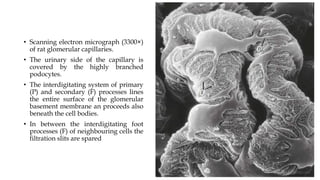

The glomerulus consists of three main cell types - mesangial cells, endothelial cells, and podocytes. The glomerular basement membrane anchors the glomerular capillaries into the mesangial region. The glomerular filtration barrier is made up of the podocyte, glomerular basement membrane, and endothelial cell. Electron, light, and immunofluorescence microscopy can be used to examine the glomerulus and identify abnormalities of the filtration barrier that can indicate different renal pathologies. Proper handling and preparation of samples is important for optimal examination and diagnosis.

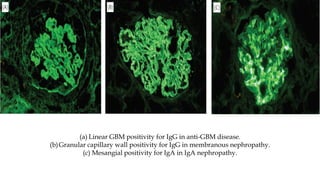

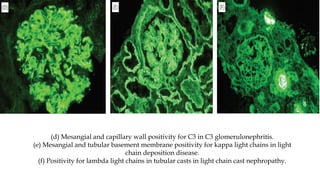

![Clinical Information

• The absence of clinical information is a sore point in many partnerships between

clinicians and pathologists.

• In an ideal world, the pathologist obtains information on the clinical history, recent

laboratory values in particular urine (proteinuria, haematuria, leukocyturia, cylindruria)

and serum [urea, creatinine, cholesterol, total protein, creatine clearance, C3, C4, ANA,

ANCA, Anti GBM], presence of diabetes mellitus or hypertension or other systemic

diseases, other parameters of interest (if available) and current therapy](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/renalpathology-210419141429/85/Renal-pathology-19-320.jpg)