This document provides information on rapidly progressive renal failure (RPRF), including its definition, causes, investigations, diagnosis, and treatment. Key points:

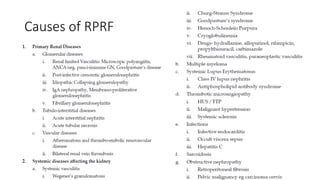

- RPRF is characterized by progressive renal failure over weeks that is not due to acute kidney injury or chronic kidney disease. The kidney biopsy often shows lesions in the glomerular, tubulointerstitial, or vascular compartments.

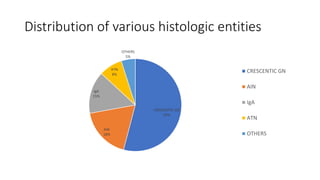

- Common causes of RPRF include crescentic glomerulonephritis (seen in 54% of cases), acute interstitial nephritis (18%), and IgA nephropathy (15%).

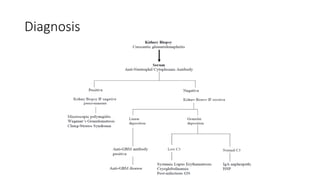

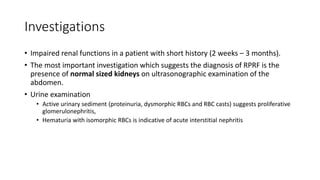

- Diagnosis involves ruling out other causes through history, physical exam, labs, and

![Types

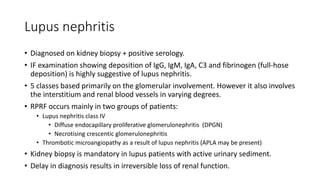

• The disease can be primary or secondary. Primary or idiopathic crescentic

glomerulonephritis is classified into the following types:

• Type 1 (anti-glomerular basement membrane [GBM] disease) presents with linear

deposits of immunoglobulin G (IgG)

• Type 2 (immune-complex mediated) presents with granular deposits of

immunoglobulin

• Type 3 (pauci-immune) presents with few or no immune deposits, antineutrophil

cytoplasmic antibody-associated small vessel vasculitis (SVV) that may be renal-

limited or part of a systemic disease, for example, granulomatosis with polyangiitis

(GPA).

• Type 4 includes combinations of types 1 and 3

• Type 5 is ANCA-negative, pauci-immune renal vasculitis (5% to 10% of cases)](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/rprf-210419141430/85/Rapidly-progressive-renal-failure-13-320.jpg)