This document discusses radiative processes in electronically excited states, including fluorescence and phosphorescence. It provides definitions and explanations of key concepts:

- Fluorescence occurs between states of the same spin multiplicity and is fast, while phosphorescence occurs between states of different spin multiplicity and is slower.

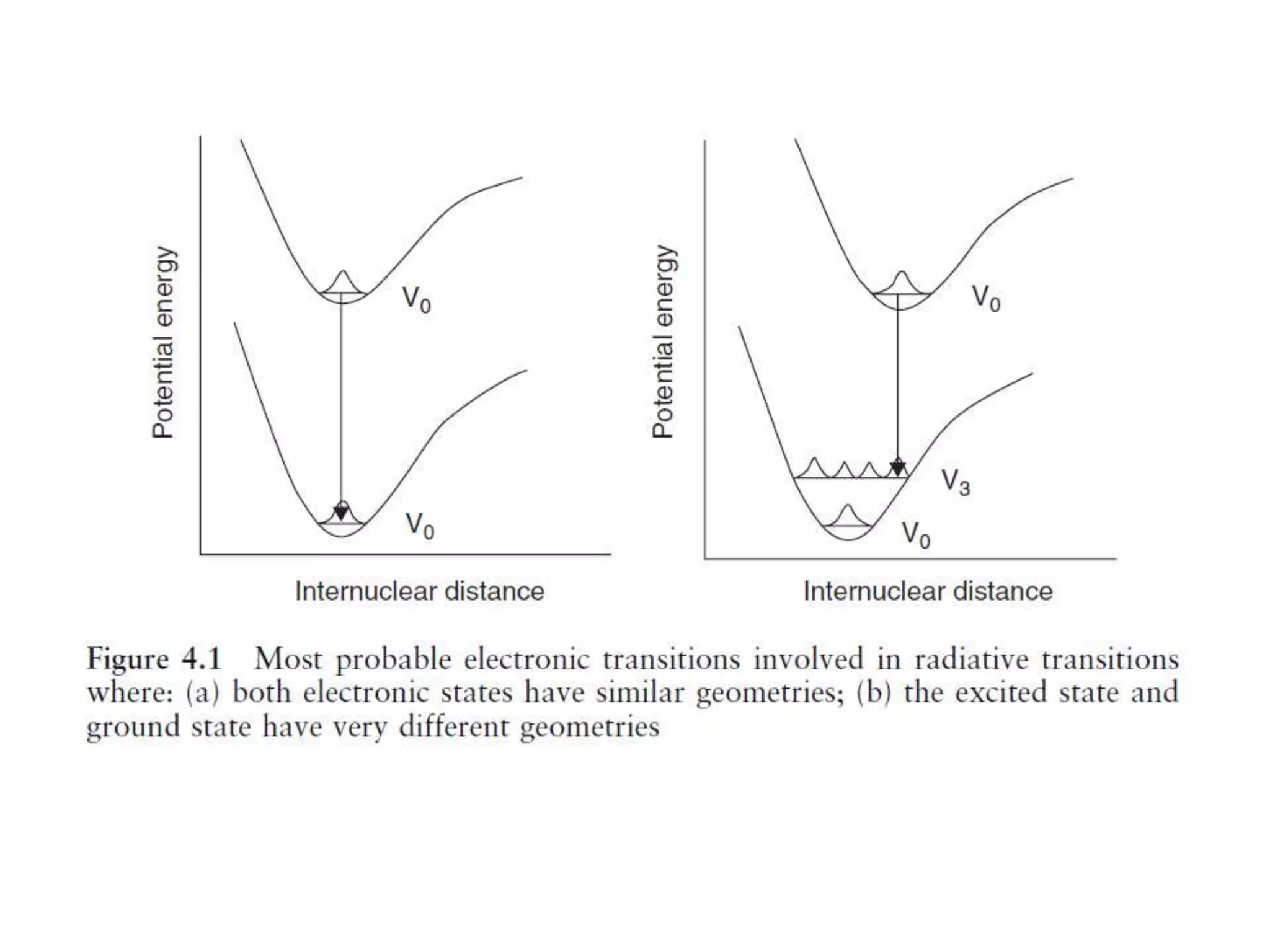

- Radiative transitions follow the Franck-Condon principle and vertical transitions.

- Mirror-image symmetry exists between absorption and fluorescence emission spectra when the ground and excited state geometries are similar.

- Exceptions to Kasha's rule exist, such as the fluorescence from the S2 state in azulene.

- Factors like molecular rigidity, substituent groups, and heavy atoms can influence fluorescence behavior and