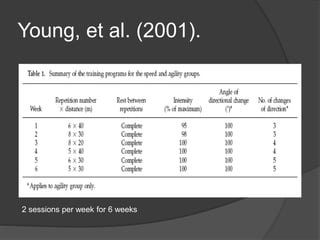

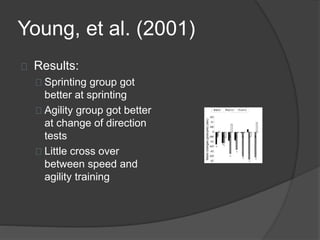

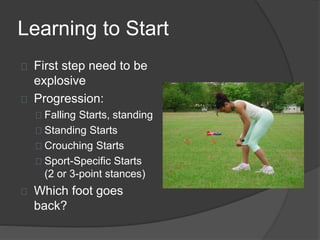

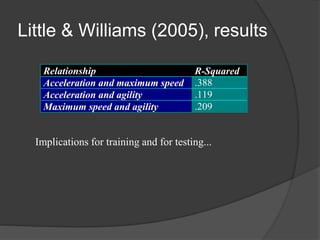

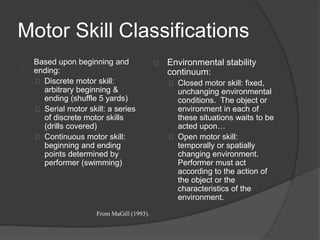

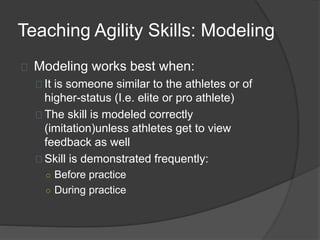

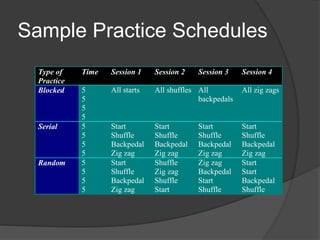

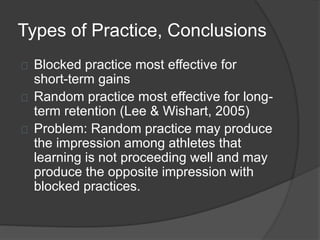

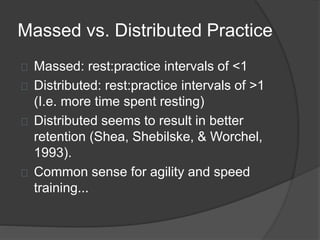

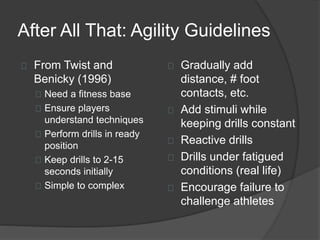

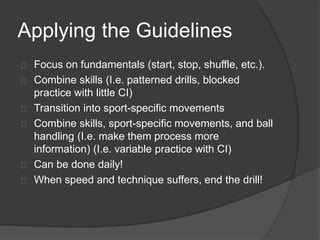

The document reviews the state of agility training research, emphasizing the challenges in improving agility and the limited transfer of skills between speed and agility. Key factors influencing agility development include strength, acceleration, and fundamental motor skills, alongside effective practice methods such as variability and specificity. The document also outlines best practices for teaching agility, highlighting the importance of combining skills with sport-specific movements and the role of feedback in motor learning.