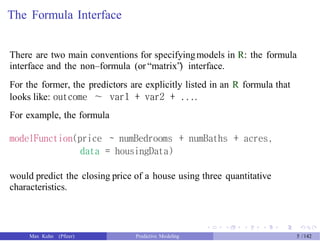

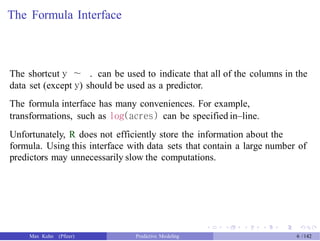

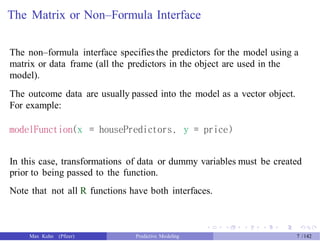

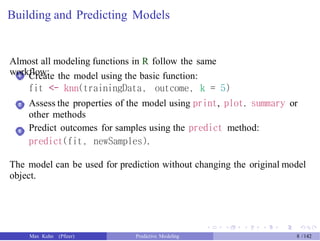

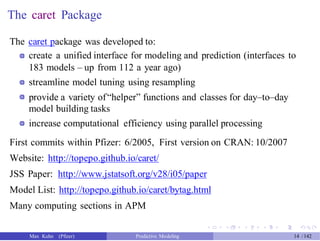

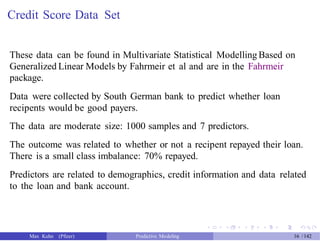

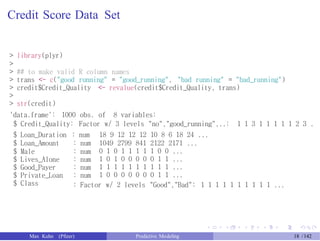

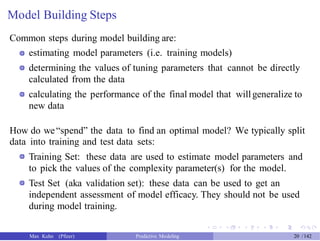

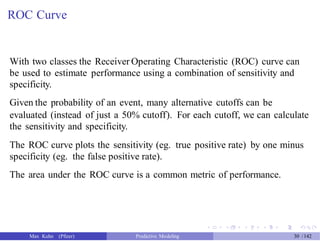

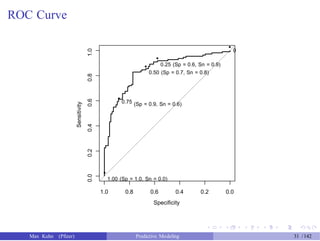

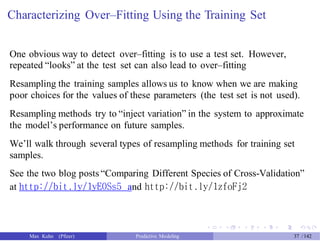

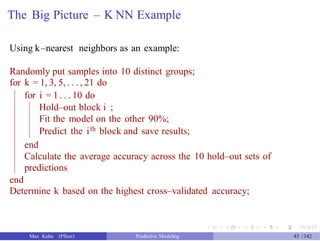

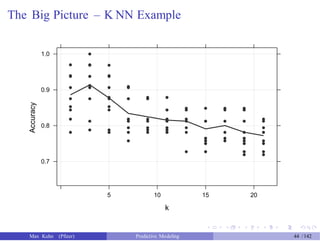

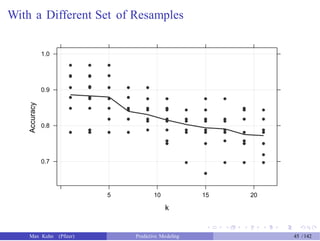

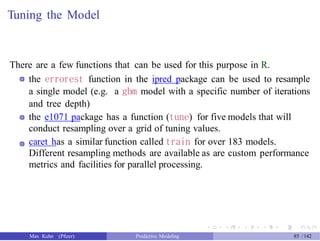

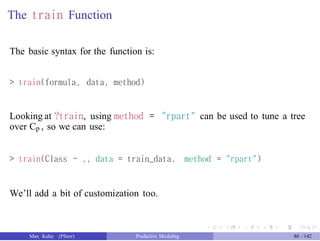

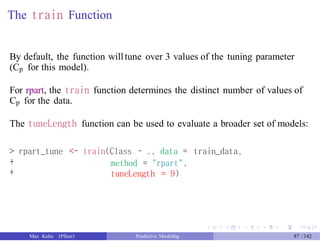

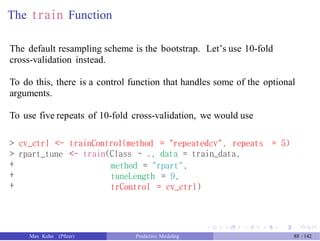

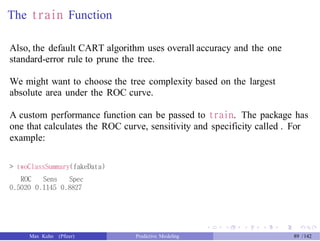

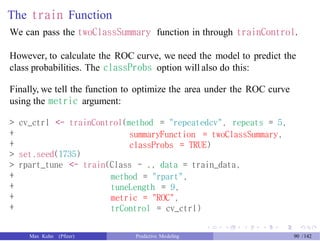

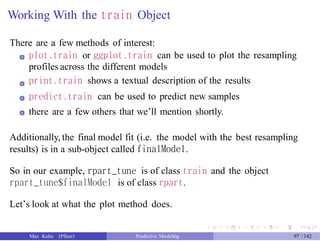

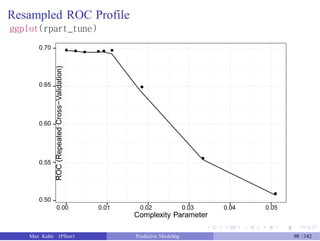

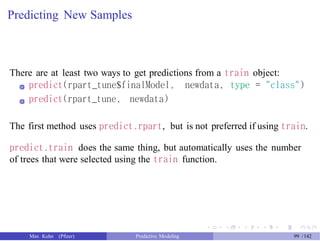

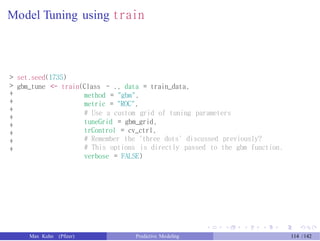

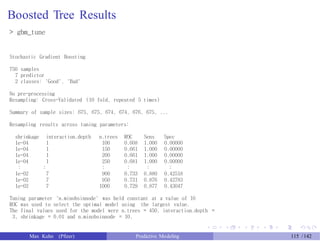

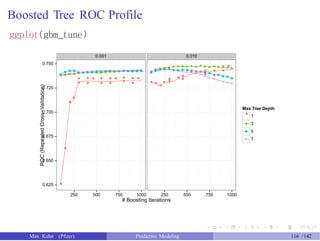

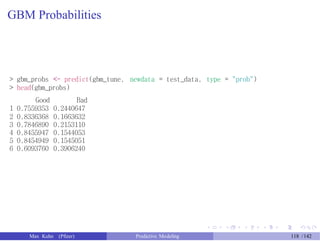

The document presents a comprehensive workshop on predictive modeling by Max Kuhn, covering essential concepts such as data types, modeling conventions in R, model building and evaluation, and various predictive modeling methods. It emphasizes the importance of splitting data for training and testing to avoid overfitting and discusses performance metrics for regression and classification models, including the use of ROC curves and confusion matrices. Additionally, it introduces the 'caret' package as a unified interface for modeling and streamlining processes in R.

![Credit Score Data Set

>

>

>

>

>

>

>

>

>

>

>

>

>

>

>

>

>

>

>

>

## translations, formatting, and dummy variables

library(Fahrmeir)

data(credit)

credit$Male <-ifelse(credit$Sexo == "hombre", 1, 0)

credit$Lives_Alone <-ifelse(credit$Estc == "vive solo", 1, 0)

credit$Good_Payer <-ifelse(credit$Ppag == "pre buen pagador", 1, 0)

credit$Private_Loan <-ifelse(credit$Uso == "privado", 1, 0)

credit$Class <-ifelse(credit$Y == "buen", "Good", "Bad")

credit$Class <- factor(credit$Class, levels = c("Good", "Bad"))

credit$Y <- NULL

credit$Sexo <- NULL

credit$Uso <- NULL

credit$Ppag <- NULL

credit$Estc <- NULL

names(credit)[names(credit) == "Mes"] <- "Loan_Duration"

names(credit)[names(credit) == "DM"] <- "Loan_Amount"

names(credit)[names(credit) == "Cuenta"] <- "Credit_Quality"

Max Kuhn (Pfizer) Predictive Modeling 17 /142](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/maxkuhnpredictivemodelingworkshop-150603155123-lva1-app6891/85/Predictive-Modeling-Workshop-18-320.jpg)

![Credit Data Set

For these data, let’s take a stratified random sample of 760 loans for

training.

> set.seed(8140)

> in_train <- createDataPartition(credit$Class, p = .75, list = FALSE)

> head(in_train)

Resample1

[1,]

[2,]

[3,]

[4,]

[5,]

[6,]

1

2

3

4

5

8

> train_data <- credit[ in_train,]

> test_data <- credit[-in_train,]

Max Kuhn (Pfizer) Predictive Modeling 23 /142](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/maxkuhnpredictivemodelingworkshop-150603155123-lva1-app6891/85/Predictive-Modeling-Workshop-24-320.jpg)

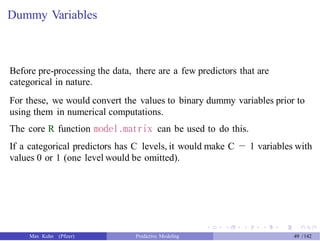

![Dummy Variables

> alt_data <- model.matrix(Class ~ ., data = train_data)

> alt_data[1:4, 1:3]

(Intercept) Credit_Qualitygood_running Credit_Qualitybad_running

1

2

3

4

1

1

1

1

0

0

0

0

0

0

1

0

We can get rid of the intercept column and use this data.

However, we would want to apply this same transformation to new data

sets.

The caret function dummyVars has more options and can be applied to any

data

Note: using the formula method with models automatically handles this.

Max Kuhn (Pfizer) Predictive Modeling 51 /142](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/maxkuhnpredictivemodelingworkshop-150603155123-lva1-app6891/85/Predictive-Modeling-Workshop-52-320.jpg)

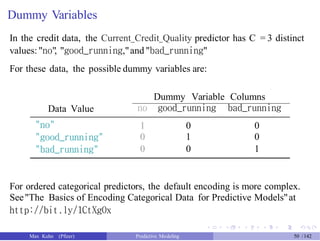

![Dummy Variables

> dummy_info <- dummyVars(Class ~ ., data = train_data)

> dummy_info

Dummy Variable Object

Formula: Class ~ .

8 variables, 2 factors

Variables and levels will be separated by '.'

A less than full rank encoding is used

> train_dummies <- predict(dummy_info, newdata = train_data)

> train_dummies[1:4, 1:3]

Credit_Quality.no Credit_Quality.good_running Credit_Quality.bad_running

1

2

3

4

1

1

0

1

0

0

0

0

0

0

1

0

> test_dummies <- predict(dummy_info, newdata = test_data)

Max Kuhn (Pfizer) Predictive Modeling 52 /142](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/maxkuhnpredictivemodelingworkshop-150603155123-lva1-app6891/85/Predictive-Modeling-Workshop-53-320.jpg)

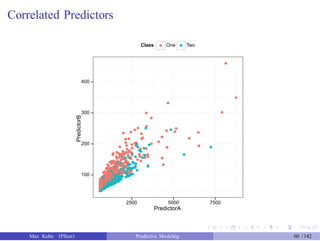

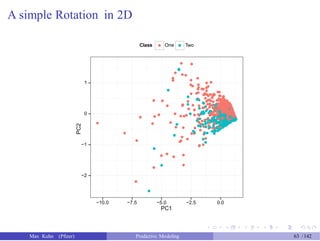

![An Example

Another data set shows an nice example of PCA. There are two the

predictors and two classes:

> dim(example_train)

[1] 1009 3

> dim(example_test)

[1] 1010 3

> head(example_train)

PredictorA PredictorB Class

2

3

4

12

15

16

3278.726

1727.410

1194.932

1027.222

1035.608

1433.918

154.89876

84.56460

101.09107

68.71062

73.40559

79.47569

One

Two

One

Two

One

One

Max Kuhn (Pfizer) Predictive Modeling 59 /142](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/maxkuhnpredictivemodelingworkshop-150603155123-lva1-app6891/85/Predictive-Modeling-Workshop-60-320.jpg)

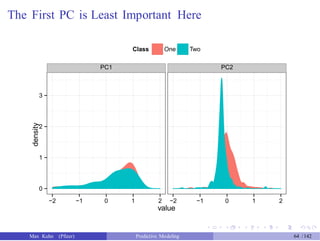

![An Example

> pca_pp <- preProcess(example_train[, 1:2],

+

> pca_pp

method = "pca") # also added "center" and "scale"

Call:

preProcess.default(x = example_train[, 1:2], method = "pca")

Created from 1009 samples and 2 variables

Pre-processing: principal component signal extraction, scaled, centered

PCA needed 2 components to capture 95 percent of the variance

> train_pc <- predict(pca_pp, example_train[, 1:2])

> test_pc <- predict(pca_pp, example_test[, 1:2])

> head(test_pc, 4)

PC1

1 0.8420447

5 0.2189168

6 1.2074404

PC2

0.07284802

0.04568417

-0.21040558

7 1.1794578 -0.20980371

Max Kuhn (Pfizer) Predictive Modeling 62 /142](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/maxkuhnpredictivemodelingworkshop-150603155123-lva1-app6891/85/Predictive-Modeling-Workshop-63-320.jpg)

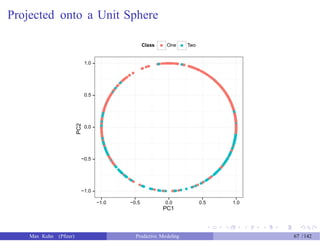

![Adding Another Step

> pca_ss_pp <- preProcess(example_train[, 1:2],

+

> pca_ss_pp

method = c("pca", "spatialSign"))

Call:

preProcess.default(x = example_train[, 1:2], method = c("pca", "spatialSign"))

Created from 1009 samples and 2 variables

Pre-processing: principal component signal extraction, spatial

sign transformation, scaled, centered

PCA needed 2 components to capture 95 percent of the variance

> train_pc_ss <- predict(pca_ss_pp, example_train[, 1:2])

> test_pc_ss <- predict(pca_ss_pp, example_test[, 1:2])

> head(test_pc_ss, 4)

PC1

1 0.9962786

5 0.9789121

6 0.9851544

PC2

0.08619129

0.20428207

-0.17167058

7 0.9845449 -0.17513231

Max Kuhn (Pfizer) Predictive Modeling 66 /142](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/maxkuhnpredictivemodelingworkshop-150603155123-lva1-app6891/85/Predictive-Modeling-Workshop-67-320.jpg)

![Example: Encoding Time and Date Data

I have found the lubridate package to be invaluable in these cases.

Let’s load some example dates from an existing RData file:

> day_values <- c("2015-05-10", "1970-11-04", "2002-03-04", "2006-01-13")

> class(day_values)

[1] "character"

> library(lubridate)

> days <- ymd(day_values)

> str(days)

POSIXct[1:4], format: "2015-05-10" "1970-11-04" "2002-03-04" "2006-01-13"

Max Kuhn (Pfizer) Predictive Modeling 72 /142](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/maxkuhnpredictivemodelingworkshop-150603155123-lva1-app6891/85/Predictive-Modeling-Workshop-73-320.jpg)

![Example: Encoding Time and Date Data

> day_of_week <- wday(days, label = TRUE)

> day_of_week

[1] Sun Wed Mon Fri

Levels: Sun < Mon < Tues < Wed < Thurs < Fri < Sat

> year(days)

[1] 2015 1970 2002 2006

> week(days)

[1] 19 45 10 2

> month(days, label = TRUE)

[1] May Nov Mar Jan

12 Levels: Jan < Feb < Mar < Apr < May < Jun < Jul < Aug < Sep < ... < Dec

> yday(days)

[1] 130 308 63 13

Max Kuhn (Pfizer) Predictive Modeling 73 /142](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/maxkuhnpredictivemodelingworkshop-150603155123-lva1-app6891/85/Predictive-Modeling-Workshop-74-320.jpg)

![Test Set Results

> rpart_pred <- predict(rpart_full, newdata = test_data, type = "class")

> confusionMatrix(data = rpart_pred, reference = test_data$Class)

Confusion Matrix and Statistics

# requires 2 factor vectors

Reference

Prediction Good Bad

Good 163 49

Bad 12 26

Accuracy : 0.756

95% CI : (0.6979, 0.8079)

No Information Rate : 0.7

P-Value [Acc > NIR] : 0.02945

Kappa : 0.3237

Mcnemar's Test P-Value : 4.04e-06

Sensitivity : 0.9314

Specificity : 0.3467

Pos Pred Value : 0.7689

Neg Pred Value : 0.6842

Prevalence : 0.7000

Detection Rate : 0.6520

Detection Prevalence : 0.8480

Balanced Accuracy : 0.6390

'Positive' Class : Good

Max Kuhn (Pfizer) Predictive Modeling 83 /142](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/maxkuhnpredictivemodelingworkshop-150603155123-lva1-app6891/85/Predictive-Modeling-Workshop-84-320.jpg)

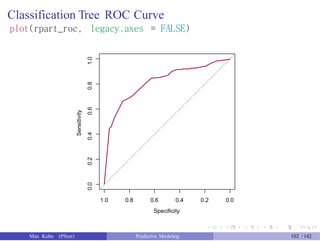

![Creating the ROC Curve

The pROC package can be used to create ROC curves.

The function roc is used to capture the data and compute the ROC curve.

The functions plot.roc and auc.roc generate plot and area under the

curve, respectively.

> class_probs <- predict(rpart_full, newdata = test_data)

> head(class_probs, 3)

Good Bad

6 0.8636364 0.1363636

7 0.8636364 0.1363636

13 0.8636364 0.1363636

> library(pROC)

> ## The roc function assumes the *second* level is the one of

> ## interest, so we use the 'levels' argument to change the order.

> rpart_roc <- roc(response = test_data$Class, predictor = class_probs[, "Good"],

+ levels = rev(levels(test_data$Class)))

> ## Get the area under the ROC curve

> auc(rpart_roc)

Area under the curve: 0.7975

Max Kuhn (Pfizer) Predictive Modeling 84 /142](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/maxkuhnpredictivemodelingworkshop-150603155123-lva1-app6891/85/Predictive-Modeling-Workshop-85-320.jpg)

![Test Set Results

> rpart_pred2 <- predict(rpart_tune, newdata = test_data)

> confusionMatrix(rpart_pred2, test_data$Class)

Confusion Matrix and Statistics

Reference

Prediction Good Bad

Good 161 47

Bad 14 28

Accuracy : 0.756

95% CI : (0.6979, 0.8079)

No Information Rate : 0.7

P-Value [Acc > NIR] : 0.02945

Kappa : 0.3355

Mcnemar's Test P-Value : 4.182e-05

Sensitivity : 0.9200

Specificity : 0.3733

Pos Pred Value : 0.7740

Neg Pred Value : 0.6667

Prevalence : 0.7000

Detection Rate : 0.6440

Detection Prevalence : 0.8320

Balanced Accuracy : 0.6467

'Positive' Class : Good

Max Kuhn (Pfizer) Predictive Modeling 100 /142](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/maxkuhnpredictivemodelingworkshop-150603155123-lva1-app6891/85/Predictive-Modeling-Workshop-101-320.jpg)

![Predicting Class Probabilities

predict.train has an argument type that can be used to get predicted

class probabilities for different models:

> rpart_probs <- predict(rpart_tune, newdata = test_data, type = "prob")

> head(rpart_probs, n = 4)

Good Bad

6 0.8636364 0.1363636

7 0.8636364 0.1363636

13 0.8636364 0.1363636

16 0.8636364 0.1363636

> rpart_roc <- roc(response = test_data$Class, predictor = rpart_probs[, "Good"],

+

> auc(rpart_roc)

levels = rev(levels(test_data$Class)))

Area under the curve: 0.8154

Max Kuhn (Pfizer) Predictive Modeling 101 /142](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/maxkuhnpredictivemodelingworkshop-150603155123-lva1-app6891/85/Predictive-Modeling-Workshop-102-320.jpg)

![gbm Predictions

We need to tell the predict method how many trees to use (let’s just pick

500).

Also, it does not predict the actual class. We’ll get the class probability

and do the conversion.

> gbm_pred <- predict(gbm_fit, newdata = test_data, n.trees = 100,

+

+

> head(gbm_pred)

## This calculates the class probs

type = "response")

[1] 0.6803420 0.7628453 0.6882552 0.8262940 0.8861083 0.7280930

> gbm_pred <- factor(ifelse(gbm_pred > .5, "Good", "Bad"),

+

> head(gbm_pred)

levels = c("Good", "Bad"))

[1] Good Good Good Good Good Good

Levels: Good Bad

Max Kuhn (Pfizer) Predictive Modeling 110 /142](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/maxkuhnpredictivemodelingworkshop-150603155123-lva1-app6891/85/Predictive-Modeling-Workshop-111-320.jpg)

![Test Set Results

> confusionMatrix(gbm_pred, test_data$Class)

Confusion Matrix and Statistics

Reference

Prediction Good Bad

Good 166 51

Bad 9 24

Accuracy : 0.76

95% CI : (0.7021, 0.8116)

No Information Rate : 0.7

P-Value [Acc > NIR] : 0.02104

Kappa : 0.3197

Mcnemar's Test P-Value : 1.203e-07

Sensitivity : 0.9486

Specificity : 0.3200

Pos Pred Value : 0.7650

Neg Pred Value : 0.7273

Prevalence : 0.7000

Detection Rate : 0.6640

Detection Prevalence : 0.8680

Balanced Accuracy : 0.6343

'Positive' Class : Good

Max Kuhn (Pfizer) Predictive Modeling 111 /142](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/maxkuhnpredictivemodelingworkshop-150603155123-lva1-app6891/85/Predictive-Modeling-Workshop-112-320.jpg)

![Another Digression – The Ellipses

R has a great feature known as the ellipses(aka "three dots") where an

arbitrary number of function arguments can be pass through nested

function calls. For example:

> average <- function(dat, ...) mean(dat, ...)

> names(formals(mean.default))

[1] "x" "trim" "na.rm" "..."

> average(dat = c(1:10, 100))

[1] 14.09091

> average(dat = c(1:10, 100), trim = .1)

[1] 6

train is structured to take full advantage of this so that arguments can

be passed to the underlying model function (e.g. rpart, gbm) when calling

the train function.

Max Kuhn (Pfizer) Predictive Modeling 113 /142](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/maxkuhnpredictivemodelingworkshop-150603155123-lva1-app6891/85/Predictive-Modeling-Workshop-114-320.jpg)

![Test Set Results

> gbm_pred <- predict(gbm_tune, newdata = test_data) # Magic!

> confusionMatrix(gbm_pred, test_data$Class)

Confusion Matrix and Statistics

Reference

Prediction Good Bad

Good 167 52

Bad 8 23

Accuracy : 0.76

95% CI : (0.7021, 0.8116)

No Information Rate : 0.7

P-Value [Acc > NIR] : 0.02104

Kappa : 0.3135

Mcnemar's Test P-Value : 2.836e-08

Sensitivity : 0.9543

Specificity : 0.3067

Pos Pred Value : 0.7626

Neg Pred Value : 0.7419

Prevalence : 0.7000

Detection Rate : 0.6680

Detection Prevalence : 0.8760

Balanced Accuracy : 0.6305

'Positive' Class : Good

Max Kuhn (Pfizer) Predictive Modeling 117 /142](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/maxkuhnpredictivemodelingworkshop-150603155123-lva1-app6891/85/Predictive-Modeling-Workshop-118-320.jpg)

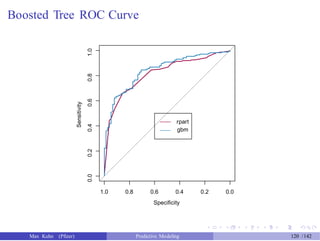

![Boosted Tree ROC Curve

> gbm_roc <- roc(response = test_data$Class, predictor = gbm_probs[, "Good"],

+

> auc(rpart_roc)

levels = rev(levels(test_data$Class)))

Area under the curve: 0.8154

> auc(gbm_roc)

Area under the curve: 0.8422

> plot(rpart_roc, col = "#9E0142", legacy.axes = FALSE)

> plot(gbm_roc, col = "#3288BD", legacy.axes = FALSE, add = TRUE)

> legend(.6, .5, legend = c("rpart", "gbm"),

+

+

lty = c(1, 1),

col = c("#9E0142", "#3288BD"))

Max Kuhn (Pfizer) Predictive Modeling 119 /142](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/maxkuhnpredictivemodelingworkshop-150603155123-lva1-app6891/85/Predictive-Modeling-Workshop-120-320.jpg)

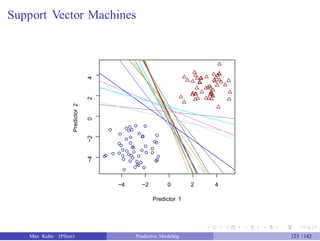

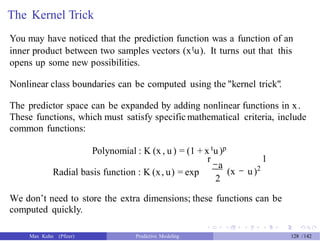

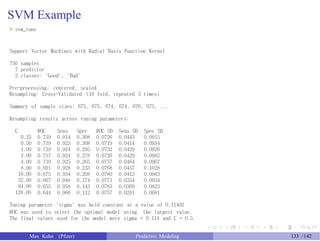

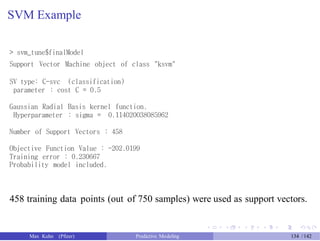

![Tuning SVM Models

We need to come up with reasonable choices for the cost parameter and

any other parameters associated with the kernel, such as

polynomial degree for the polynomial kernel

a, the scale parameter for radial basis functions (RBF)

We’ll focus on RBF kernel models here, so we have two tuning parameters.

However, there is a potential shortcut for RBF kernels. Reasonable values

of a can be derived from elements of the kernel matrix of the training set.

The manual for the sigest function in kernlab has "The estimation [for a]

is based upon the 0.1 and 0.9 quantile of lx - x tl2."

Anecdotally, we have found that the mid-point between these two

numbers can provide a good estimate for this tuning parameter. This

leaves only the cost function for tuning.

Max Kuhn (Pfizer) Predictive Modeling 131 /142](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/maxkuhnpredictivemodelingworkshop-150603155123-lva1-app6891/85/Predictive-Modeling-Workshop-132-320.jpg)

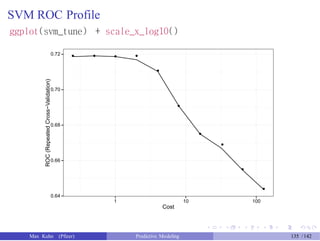

![Test Set Results

> svm_pred <- predict(svm_tune, newdata = test_data)

> confusionMatrix(svm_pred, test_data$Class)

Confusion Matrix and Statistics

Reference

Prediction Good Bad

Good 165 49

Bad 10 26

Accuracy : 0.764

95% CI : (0.7064, 0.8152)

No Information Rate : 0.7

P-Value [Acc > NIR] : 0.01474

Kappa : 0.34

Mcnemar's Test P-Value : 7.53e-07

Sensitivity : 0.9429

Specificity : 0.3467

Pos Pred Value : 0.7710

Neg Pred Value : 0.7222

Prevalence : 0.7000

Detection Rate : 0.6600

Detection Prevalence : 0.8560

Balanced Accuracy : 0.6448

'Positive' Class : Good

Max Kuhn (Pfizer) Predictive Modeling 136 /142](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/maxkuhnpredictivemodelingworkshop-150603155123-lva1-app6891/85/Predictive-Modeling-Workshop-137-320.jpg)

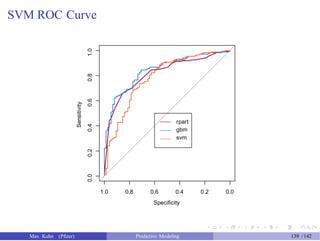

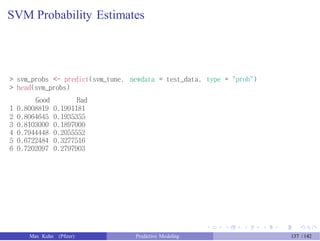

![SVM ROC Curve

> svm_roc <- roc(response = test_data$Class, predictor = svm_probs[, "Good"],

+

> auc(rpart_roc)

levels = rev(levels(test_data$Class)))

Area under the curve: 0.8154

> auc(gbm_roc)

Area under the curve: 0.8422

> auc(svm_roc)

Area under the curve: 0.7838

> plot(rpart_roc, col = "#9E0142", legacy.axes = FALSE)

> plot(gbm_roc, col = "#3288BD", legacy.axes = FALSE, add = TRUE)

> plot(svm_roc, col = "#F46D43", legacy.axes = FALSE, add = TRUE)

> legend(.6, .5, legend = c("rpart", "gbm", "svm"),

+

+

lty = c(1, 1, 1),

col = c("#9E0142", "#3288BD", "#F46D43"))

Max Kuhn (Pfizer) Predictive Modeling 138 /142](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/maxkuhnpredictivemodelingworkshop-150603155123-lva1-app6891/85/Predictive-Modeling-Workshop-139-320.jpg)