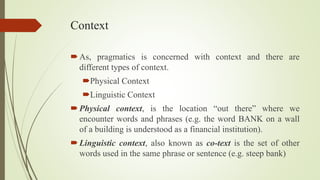

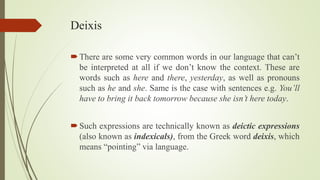

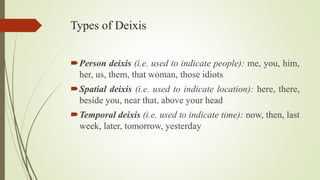

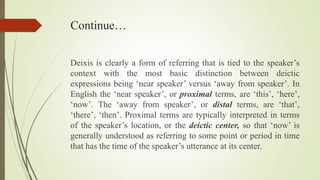

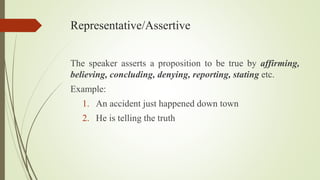

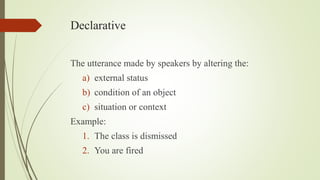

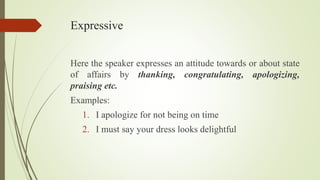

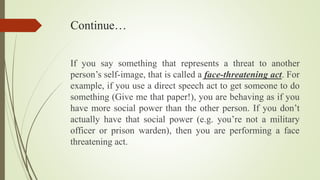

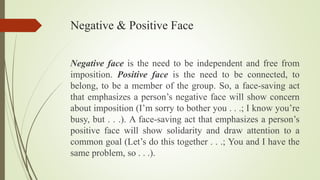

Pragmatics is the study of contextual meaning and speaker meaning. It examines how context contributes to meaning. Some key concepts in pragmatics include deixis, which examines words like I, you, here, and now that depend on context; presupposition, which are assumptions in language; speech acts, which are actions performed through language like requests or promises; and politeness, which is using language to respect face or self-image. Pragmatics analyzes how people communicate beyond just the words themselves.