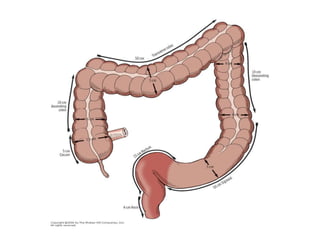

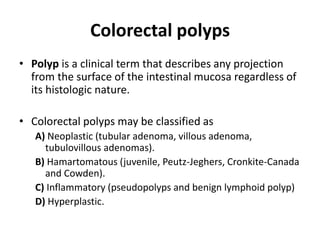

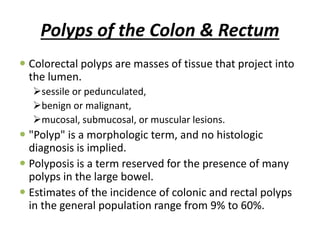

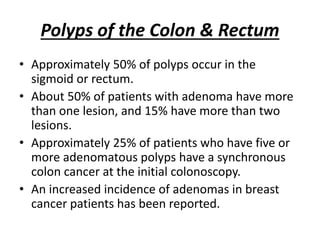

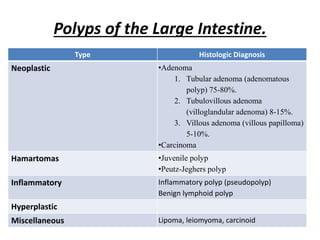

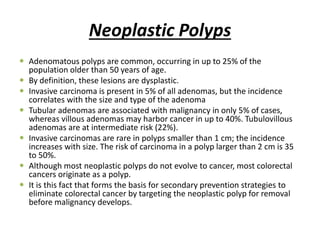

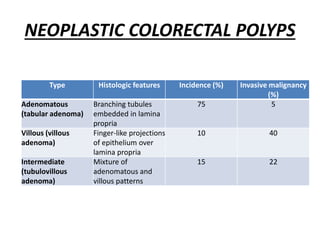

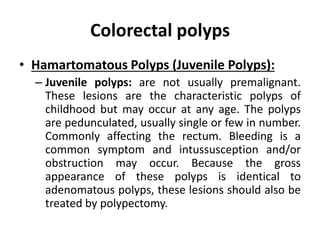

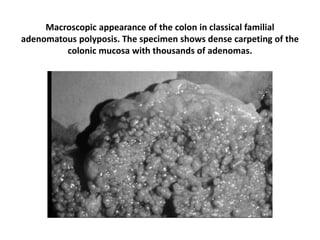

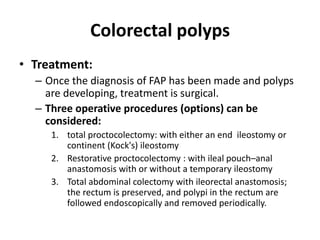

Colorectal polyps are tissue growths in the colon classified as neoplastic, hamartomatous, inflammatory, or hyperplastic, with varying risks of malignancy. Adenomatous polyps are common and can lead to colorectal cancer if not removed, particularly when they exceed 2 cm in size. Familial adenomatous polyposis is a genetic condition that results in numerous adenomas and a nearly 100% risk of colorectal cancer by age 50 if untreated.

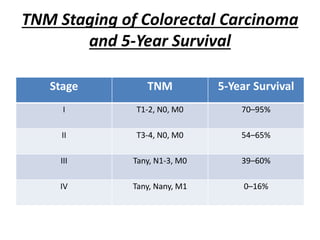

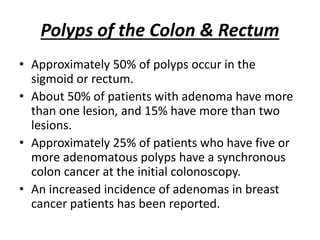

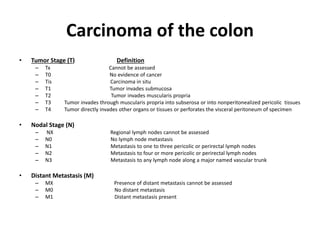

![Stage Grouping

STAGE T N M DUKES[§]

0 Tis N0 M0

I T1 N0 M0 A

T2 N0 M0 A

IIA T3 N0 M0 B

IIB T4 N0 M0 B

IIIA T1-T2 N1 M0 C

IIIB T3-T4 N1 M0 C

IIIC Any T N2 M0 C

IV Any T Any N M1](https://image.slidesharecdn.com/polyposiscancecolon-160913104535/85/Polyposis-Cancer-Colon-28-320.jpg)